Unless otherwise stated all pictures on Berlioz Photos pages have been scanned from engravings, paintings, postcards and other publications in our collection. All rights of reproduction reserved.

This page includes portraits or photographs of the following: Estelle Fornier, Camille Moke, Jean-François Lesueur, Franz Liszt, Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, The Bertin family, Alfred de Vigny, Théophile Gautier, Pauline Viardot, Jules Janin.

![]()

As any reader of the Memoirs knows, Estelle Dubœuf, later Estelle Fornier, played a central role in Berlioz’s life: she was his first and last love (Memoirs chapters 3, 58 and the concluding Voyage en Dauphiné).

This photo was taken when Mme Fornier was in Geneva; she sent a copy to Berlioz (Voyage en Dauphiné (near the end); CG no. 2970). A copy of the photo is now in the Hector Berlioz Museum at La Côte Saint-André. See also the pages on Meylan, where Berlioz first met his ‘Stella montis’, on Geneva, where he visited her in 1865 and 1866, and on the composition of the Memoirs.

© Musée Hector-Berlioz

The above portrait was acquired by the Musée Hector-Berlioz in 2010 from descendants of the Fornier family. We are most grateful to the Museum for granting us permission to reproduce it on this page.

A copy of this picture is in the Hector Berlioz Museum at La Côte Saint-André.

Camille Moke, a talented and attractive pianist, met Berlioz met early in 1830, the year when Berlioz competed for the Prix de Rome prize for musical composition. They became engaged, but in 1831, while Berlioz was in Italy as a Prix de Rome laureate, she broke off the engagement to marry Camille Pleyel, a rich piano manufacturer (the marriage broke down a few years later). Berlioz alludes to these events in his Memoirs, but without naming Camille Moke (chapters 28 and 34; see also the earlier presentation of this story in the Voyage Musical of 1844). Berlioz’s account is deliberately light-hearted, though from his correspondence in 1830 it is clear how attached he had been to Camille Moke (see the letters CG nos. 166 through to 183), and how deeply he was hurt by her betrayal in 1831 (see the pages on Genoa and Nice). Berlioz later took literary revenge on Camille Moke in the novel Euphonia, first published in 1844, where Camille is transparently presented as Ellimac; it was later reproduced in the Soirées de l’orchestre, where she is now Mina and comes to a gruesome end (25th evening).

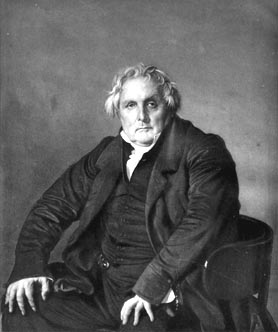

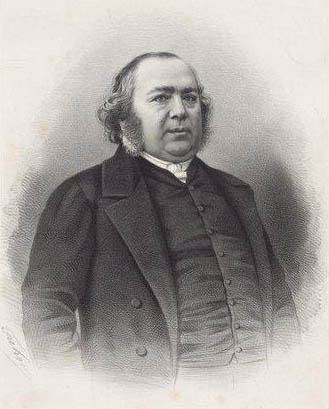

Of the two teachers that Berlioz had at the Conservatoire, Berlioz was closer to Lesueur, his teacher in composition, than to Anton Reicha, his teacher in harmony and counterpoint (on whom cf. Memoirs, chapter 13 and the obituary he wrote in the Journal des Débats, 3 July 1836). Berlioz formally enrolled as a student at the Conservatoire only in October 1826, but he had been a private pupil of Lesueur since 1823, and from the start teacher and pupil developed a close relationship; the two shared a common admiration for Gluck, Virgil, and Napoleon. Lesueur was devoted to all his students, but he recognised Berlioz’s exceptional potential and gave him from the start his full support. When Berlioz won the Prix de Rome in 1830 Lesueur wrote a letter to Dr Berlioz predicting that his son would make the name of Berlioz famous and might well become the Napoleon of music (NL no. 173bis pp. 86-88; 25 August 1830).

The name of Lesueur figures frequently in Berlioz’s many writings, but there is a noticeable difference in tone between the presentation in the Memoirs, written and revised later in Berlioz’s life, and the evidence of the feuilletons that Berlioz wrote, especially those of the 1830s. There are also numerous mentions of Lesueur in the composer’s correspondence (see for example CG nos. 61, 63, 76, 95, 132, 171, 172, 188).

In the Memoirs Berlioz remembered with affectionate nostalgia his student days in the company of Lesueur, and was full of praise for his kindness and the support he gave him. But he was rather cool about Lesueur’s own music, critical of his musical theories and the importance he attached to them, and critical also of Lesueur’s lack of interest in instrumental music. He felt that he had not learned anything from Lesueur (or from Reicha) about instruments and orchestral writing, and was particularly disappointed at Lesueur’s failure to acknowledge the significance of Beethoven’s music (on all this see Memoirs chapters 6, 7, 10, 11 [end], 13 and 20; see also the discussion of Lesueur’s theories about ancient music near the end of the opening chapter of À Travers chants.

The articles in the Débats tell a fuller and more positive story, and suggest a greater affinity with his master than the Memoirs acknowledge. Very soon after joining the journal as its music critic, Berlioz devoted several articles to Lesueur and his music. He praised Lesueur’s judicious use of fugues in religious music, which departed from standard practice (9 August 1935). He emphasized the originality of his style and harmony, and extolled particularly Lesueur’s oratorios on biblical subjects, their antique colour and charm, and their delicate orchestration (21 November 1835), using words that could be applied to Berlioz’s own biblical oratorio l’Enfance du Christ, written many years later. After Lesueur’s death in 1837 Berlioz wrote a warm obituary where he reviewed at length his master’s career and works, praising again his originality and independence of mind, and celebrating his devotion to his students (15 October 1837; cf. also 15 July 1838). Subsequently Lesueur’s name reappears intermittently in Berlioz’s articles. He praised Lesueur’s setting of Paul et Virginie above the better known one by Kreutzer (30 August 1846). He warmly welcomed the decision of the city of Abbeville to set up a statue of Lesueur and the support given to it by Napoleon III (27 August 1850). He drew attention to the performance of two choral pieces by Lesueur by his own Société Philharmonique on 22 October and 17 December 1850 (17 January 1851). He reviewed once more the career and achievements of Lesueur on the occasion of the inauguration of his statue at Abbeville (27 August 1852; cf. his letter the previous July to Mme Lesueur, CG no. 1506 and see below). As late as 1861 he drew his readers’ attention to the publication of the complete sacred works of Lesueur (21 December 1861).

The above 1830 engraving is reproduced here courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Lesueur was born in Abbeville, a town in the Picardie region. In August 1852 a statue was erected in the town to honour his memory. At the inauguration ceremony, attended by many people of note, speeches were made by the Mayor of the town, the president of the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut de France, and a pupil of Lesueur. In connection with this event, Berlioz devoted a substantial part of his feuilleton of the 27th August in the Journal des Débats to Lesueur and his music, and ended the piece with a report about the inauguration ceremony.

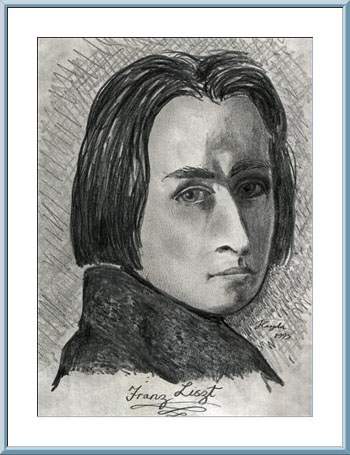

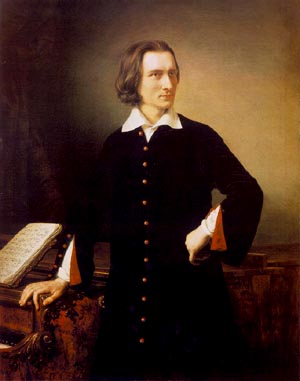

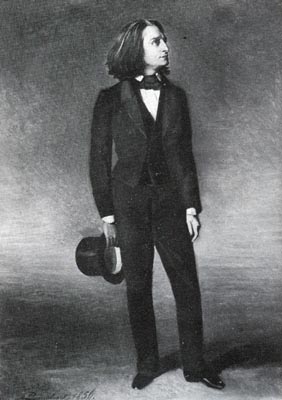

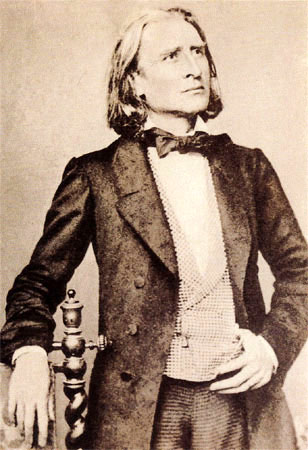

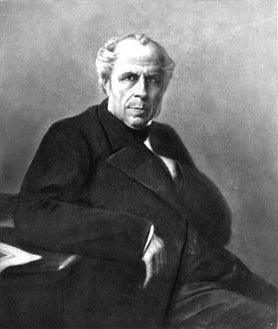

Berlioz met Liszt in 1830, when he attended the first performance of the Symphonie fantastique at the Paris Conservatoire on 5 December. They became close friends — Liszt was one of the few with whom Berlioz was on intimate tu terms; the story of their friendship, which lasted from 1830 to 1866, is related in the page on Berlioz and Liszt. See also the related page on Berlioz and Weimar, where Liszt settled in 1848 and actively promoted the music of his friend, as well as that of other contemporary composers.

The above lithograph is by Devéria, and was published in a 19th century book in our collection. A printed reproduction of the lithograph is in the Musée Hector Berlioz.

© Haydn Greenway. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

We are most grateful to Mr Greenway for sending us a copy of this drawing and granting us permission to reproduce it here.

This portrait of Liszt is by Miklós Barabás (1810-1898). The original painting is at the Hungarian National Museum / Hungarian Historical Gallery.

We are most grateful to Mr Andrea Vörös-Márky for the information regarding the location of the painting.

The above painting is by Richard Lauchert, who also painted a portrait of Berlioz in 1855 during one of his visits to Weimar.

A photo reproduced on a postcard; this copy is in our collection.

The above cabinet photo, published in the 1880s, shows the Princess with her daughter Princess Marie von Sayn-Wittgenstein in 1844; the photo is in our own collection.

The Princess was Liszt’s mistress; they had met in Kiev in 1847, and she persuaded Liszt to settle in Weimar. She became a close friend of Berlioz from the time of his visits to Weimar in the 1850s. Her greatest title to fame is to have persuaded Berlioz in 1856 to undertake the composition of his opera Les Troyens, which was subsequently dedicated to her and (retrospectively) to the poet Virgil, whose Aeneid had fired the imagination of the young Berlioz and became the subject of Les Troyens. Berlioz’ Memoirs and his correspondence with the Princess provide a detailed history of the composition of the work. Beyond the composition of the opera the Princess became Berlioz’s confidante, and their correspondence continued till 1867.

On 18 February 1855 Berlioz attended a reception at the Altenburg in Weimar for the birthday of Princess Marie; he improvised the Valse chantée par le vent on the young princess’s album.

A copy of this photograph is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

The influential Journal des Débats was owned by Louis-François Bertin and his family; it was founded by him in 1814 and continued in existence without interruption for 130 years till 1944. Bertin and his two sons Armand and François-Édouard were among Berlioz’s strongest supporters in Paris, particularly Armand who edited the journal till his death early in 1854, after which his elder brother took over. Berlioz relates in his Memoirs how he joined the Débats as a music critic in 1835 (chapter 47); during his career he contributed nearly 400 feuilletons to the journal, which are all reproduced on this site. Elsewhere in his Memoirs he mentions a number of instances where the Bertins, and particularly Armand, gave him support openly or behind the scenes (chapters 46, 49, 53, 54, 57). His correspondence also gives much evidence about his relations with the Débats and the Bertin family (CG nos. 665, 702, 1240, 1414, 1442, 1449, 1453, 1481, 1499, 1537, 1608, 1657, 1935, 2171, 2172).

Of particular interest is the support that Berlioz gave in return to the music of Louise Bertin, sister of Armand; he assisted with the preparations for her opera La Esmeralda in 1836 (based on Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris), discussed the score in a feuilleton later (Débats 15 July 1838; cf. CG no. 487), and on several other occasions mentioned favourably other pieces by her (Débats 13 April 1842, 7 June 1846, 21-22 April 1851). His seventh letter on his first trip to Germany was addressed to her (Débats 8 October 1843, later reproduced in his Memoirs).

We are most grateful to our friend Gene Halaburt for sending us the portraits of Louis-François Bertin and his sons.

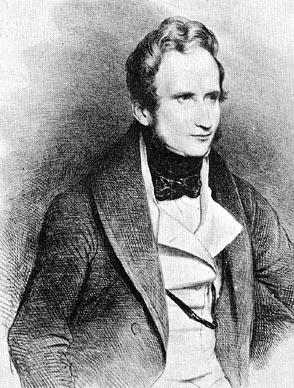

A copy of this lithograph by Achille Devéria is in the Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Among French literary figures of the time Alfred de Vigny counted as one of Berlioz’s friends and supporters from the time of the composer’s return from Italy; their relations are attested by a number of letters which extend from September 1833 to April 1861. For example de Vigny was a guest at a dinner party given by Berlioz and Harriet Smithson at their house in Montmartre in May 1834, which was also attended by Liszt, Chopin, Antoni Deschamps and Ferdinand Hiller (CG nos. 396, 397). When Berlioz’ sisters visited him in Paris in 1839 and 1840 he introduced them to Alfred de Vigny (CG nos. 651, 709).

Although Berlioz did not set any of de Vigny’s poetry to music, de Vigny indirectly influenced one of Berlioz’s major works. Berlioz was captivated by the Memoirs of Benvenuto Cellini to which he had been introduced by de Vigny, and in 1834 approached de Vigny to write a libretto for an opera on the subject. De Vigny, otherwise occupied, declined but referred Berlioz to Léon de Wailly who, together with Auguste Barbier, wrote the libretto for the opera Benvenuto Cellini. De Vigny had a hand in revising the libretto, though he declined to add his name to that of the authors (cf. CG no. 453).

Together with many other young French writers and artists, Berlioz included, Théophile Gautier was present at the celebrated performance of Hamlet at the Odéon theatre on 11 September 1827. He was present again at the première of Victor Hugo’s Hernani at the Théâtre Français on 25 February 1830, and on 9 December 1832 at the concert at the Conservatoire when the Symphonie fantastique was first performed together with its sequel Le Retour à la vie. Subsequently he was to become one of Berlioz’s active friends and supporters for many years; it is unclear when exactly they first became close, though it appears that he was a guest at a dinner party gien by Berlioz in Montmartre in October 1835 (cf. CG no. 445 with CG II p. 255 n. 2).

The known correspondence between Berlioz and Gautier extends from 1839 to 1858 and only gives a partial idea of their relations. Most of the extant letters concern announcements or reviews of concerts given by Berlioz (see for example CG nos. 899, 934), with the exception of a group of letters from late 1847 during Berlioz’s first stay in London, concerning a request by him for a ballet from Gautier (Gautier supplied the ballet, but it was not performed; cf. CG no. 1245). Gautier on his side wrote extended reviews in support of major works of Berlioz, notably Benvenuto Cellini in 1838 (reproduced on this site), Roméo et Juliette in 1839 (CG no. 693), la Damnation de Faust in 1846 (CG no. 1084), and L’Enfance du Christ in 1854 (cf. CG nos. 1670, 1813, 1816). Coincidentally Berlioz’s correspondence appears to make no reference to Gautier’s authorship of the six poems which Berlioz set to music under the title of Les Nuits d’été in 1840-1 and orchestrated later, in 1843 and 1856. It is also possible that Gautier's Le Roman de la momie may have had some influence on Berlioz’s Les Troyens

In 1857 Ernest Reyer, an admirer of Berlioz and a close friend of Gautier, published an extended article on Berlioz in a journal (L’Artiste) edited by Gautier. But in the same year Gautier published an article in praise of Wagner’s Tannhaüser with Reyer’s assistance: both were admirers of Wagner’s music as well as that of Berlioz. Berlioz’s reaction to this does not appear to be documented, but in practice his relations with Gautier seem to have become more distant. At any rate no correspondence between them is known after 1858, and they were definitely on different sides of the argument when Wagner’s Tannhaüser was performed in stormy circumstances at the Opéra in March 1861. But Gautier bore no grudge against Berlioz, and published a warm obituary of his friend in March 1869, though his article made a number of deliberate references to the music of Wagner, but without mentioning Berlioz’s antipathy to it. Reviewing Berlioz’s career and work Gautier presented his friend as a ‘true romantic’ in music; in his 1846 review of la Damnation de Faust he had described Berlioz as ‘forming with Victor Hugo and Eugène Delacroix the Trinity of Romantic Art’. In 1872 Gautier published an Histoire du romantisme. It may be worth noting that the word ‘romantic’ is not one that Berlioz used to describe himself.

The above photo was taken by Nadar around 1857.

The above lithograph by Auguste Lemoine after a photo by Pierson shows Gautier in 1860. An original copy of this lithograph is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

This steel engraving is in the Robert Schumann House, a museum in Zwickau in Germany.

‘Mme Viardot is one of the greatest artists that can be named in the past and present history of music’ wrote Berlioz in 1849, and his reviews and articles in the Journal des Débats are full of similar words of praise for her exceptional talent and versatility: she excelled in virtually every genre and style of singing, she could sing in any language, and she was a great actress as well as a great singer (see for example his feuilletons of 13 April 1850, 6 March 1857, 6 January 1858 and 16 February 1860. Berlioz discovered her talent as far back as 1841 and thereafter down to 1863 hardly a year went by without Berlioz finding occasion to mention her performances and concerts in France and elsewhere in Europe.

Viardot sang for Berlioz on many occasions: in London in 1848 and 1855, in Paris at concerts of the Société Philharmonique in 1850 and 1851, in Baden-Baden in 1856, 1859 and 1860 (cf. also Memoirs, Postface). One of her greatest successes was in the role of Orpheus in Gluck’s Orphée at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris in 1859 in a production that was supervised by Berlioz himself and won great acclaim (see below). Berlioz’s review of the performances in the Journal des Débats was reproduced by him later in À Travers chants in 1862 (chapter 9). In 1861 Viardot also sang at the Paris Opéra the role of Alceste in Gluck’s opera of that name, which prompted a series of articles on the work which Berlioz again reproduced in À Travers chants (chapters 11 and 12).

The pinnacle of Viardot’s collaboration with Berlioz should have been in the role of Dido in les Troyens à Carthage in November 1863 at the Théâtre Lyrique. Viardot had become enthusiastic about Les Troyens and had given advice to Berlioz on its composition in 1859 and 1860. She expected to be given one or even both of the title roles (Cassandra and Dido) when the work reached the stage, but Berlioz eventually changed his mind, for reasons that are not well understood. This brought about a cooling off in their relations (for further details see the page on the première of Les Troyens in 1863.

This photo of Madame Viardot was taken by Pierre Petit. A reproduction of the original photo is in our collection.

This photograph shows Madame Viardot as Orphée in Gluck’s opera at the Théâtre Lyrique in Paris in 1859, in a production supervised by Berlioz. On the career of Mme Viardot and Berlioz’s relations with her see above.

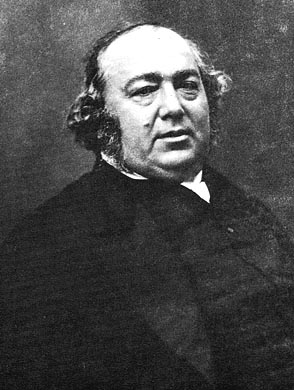

The above engraving by N. Desmadryl after a painting by E. Champmartin shows Jules Janin in 1840.

An original copy of this engraving is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Jules Janin belonged to the same circle of French literary figures from which came many of Berlioz’s natural friends and allies; he was present with them at the performances of Shakespeare plays given at the Odéon theatre in Paris in September 1827 by the company of English actors, which included the Irish actress Harriet Smithson, and which had such a profound influence on Berlioz’s life and career. He similarly attended the performance at the Conservatoire on 9 December 1832 of the Symphonie fantastique with its sequel le Retour à la vie where Harriet Smithson was also present. Around that time or soon after he became close to Berlioz and remained thereafter a lifelong friend and supporter of the composer. A critic at the Journal des Débats since 1829 he then became a close colleague of Berlioz when the composer joined the journal in 1835 as its music critic; initially Berlioz covered concerts only, then early in 1837 he took over as well operatic performances (except those at the Théâtre-Italien), while Janin kept as his domain ballet and the theatre (Memoirs chapter 47; CG no. 487). A number of letters of Berlioz to Janin are preserved ranging from 1837 to 1867, and a few are quoted on this site (CG nos. 619, 1644, 2998).

Janin’s support for Berlioz was manifested on numerous occasions. In 1838 he wrote an article, reproduced on this site, which gave maximum publicity to Paganini’s gift of 20,000 francs to Berlioz (Memoirs chapter 49). In 1839 he reviewed enthusiastically Berlioz’s symphony Roméo et Juliette (this article unexpectedly gave offence to the Berlioz family and provoked a polemical exchange of letters between Berlioz’s sister Nancy Pal and Janin). In 1846 he supplied the text for the cantata le Chant des chemins de fer which Berlioz set to music and which was performed in Lille in June of that year. When Harriet Smithson died in 1854 he wrote a moving tribute to her, based on his own experience of her acting; his article touched Berlioz greatly who quoted it extensively in his Memoirs (chapter 59).

The above photo was taken by Nadar around 1855.

The above is a lithograph by Charles-Jérémie Fuhr after the photo by Nadar. An original copy of this lithograph is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the texts and images on Berlioz Photo Album pages.

All rights of reproduction reserved.