![]()

Berlioz in Montmartre

Selected letters of Berlioz, 1834-1836

Montmartre in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

Nothing illustrates better the vast urban growth of Paris since the XIXth Century than what happened to Montmartre: nowadays it is hard to conceive that in Berlioz’s time Montmartre was not part of Paris, but a separate village. To go to Montmartre was to leave Paris for the countryside. From the north-facing slope of Montmartre the eye could contemplate a vast expanse of open ground stretching out to the plain of Saint-Denis, but which is now entirely built up. Berlioz and Harriet Smithson lived in Montmartre for a few months in 1834 and then in 1835-6, in a house located in rue Saint-Denis (later renamed rue du Mont-Cenis), at the junction with rue Saint Vincent, on the north slope of the hill.

Although Berlioz lived there for only a few years, Montmartre was charged with personal associations, both happy and sad, and his letters provide detailed information about his life there; a selection of these for the years 1834-1836 is provided below (references are all to Correspondance Générale, hereafter CG for short). It was in Montmartre that the couple enjoyed the blissful start of their married life, greeted by exceptionally fine weather in spring and the early summer of 1834 (CG nos. 395, 397). Their son Louis was born there, on 14 August 1834, to the great joy of both parents and especially of Harriet, and christened on 23 August the following year (CG nos. 409, 454, 458). For Berlioz the period in Montmartre was one of intense activity: he completed there the symphony Harold in Italy (CG nos. 398, 408), initiated the opera Benvenuto Cellini (CG nos. 398, 453), and started composing a large work in celebration of France’s great men (CG no. 440); the work was not completed but probably provided material for later works – the cantata Le Cinq mai, the Requiem, and the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale. But much of his time and energy was necessarily taken up with his work as literary critic (CG no. 440), and it was in 1834 that his long association with the Journal des Débats started, which became regular in 1835.

Montmartre had a number of advantages: the setting itself was idyllic with a large garden and a view over the plain of Saint-Denis, and Berlioz’s letters make frequent reference to this (CG nos. 385, 389, 394, 395, 435, 445, 458, 474). The cost of living was significantly lower than in Paris (CG nos. 385, 435, 445), and Berlioz was sheltered from unwanted visitors and interruptions (CG nos. 385, 445), though it was still possible to hold there social gatherings of the intelligentsia of Paris (CG nos. 396, 397, 445, 469). But Montmartre also had its drawbacks: Berlioz had to go regularly to Paris, and travel was arduous and expensive (CG no. 445); in winter Montmartre was isolated, Berlioz’s house lacked proper heating (CG nos. 454, 457, 458), and the servants were a constant source of trouble (CG nos. 439, 457, 458, 464).

It was also in Montmartre that fundamental problems came home to the couple: their financial difficulties, Berlioz’s need to write feuilletons instead of being able to compose music (CG no. 440), and the inability of Harriet to pursue the acting career which had first brought her to fame in Paris (CG nos. 439, 464). It was thus inevitable that the couple should eventually return to Paris (35 rue de Londres).

Berlioz never lived again in Montmartre, though it was to Montmartre (rue Saint-Vincent) that Harriet returned in 1848 after the breakdown of her marriage with Berlioz; she spent there the remaining years of her life until her death on 3 March 1854. She was buried in the small Saint Vincent cemetery, on the north-facing slope of Montmartre, not far from where she and Berlioz had lived, though her remains were later transferred to the larger Montmartre cemetery (3 February 1864; cf. Memoirs, Postface).

![]()

To his sister Adèle, 20 March (CG no. 385, from Paris):

[…] In a week or so we are going off to live in Montmartre, the mountain of Paris; we have a small flat with 4 rooms, a garden and a view over the plain of Saint-Denis for 70 fr. a month. It is much cheaper than here and it takes half an hour to get to Paris. I will have more peace to work, while here visitors are a nuisance. […] Our new address will be rue Saint-Denis at Montmartre near Paris. […]

To Thomas Gounet, 10 April (CG no. 389, from Montmartre):

[…] Come and see us on Sunday if you can; we will talk a little about everything which concerns you, and we will show you the beauty of our country house, which is by no means to be despised. […]

To Adèle, 29 April (CG no. 394, from Montmartre):

[…] I am working excessively hard; we enjoy such peace here in our hermitage. Only the nightingales, singing all day and night under our windows, are beginning to wear me out. […]<

To Liszt, early May (CG no. 395, from Montmartre):

[…] The weather here is like Italy, Rome and Naples, and this plain, with its new greenery, so pure and so fresh, is so beautiful today that I feel I am in Tivoli. So come and see us before the wind has covered with dust this beautiful green foliage. […]

To Chopin, between 1-4 May (CG no. 396, from Montmartre):

Chopinetto mio, si fa una villegiatura da noi in Montmartre, rue St-Denis no. 10. Spiro che Hiller, Liszt and de Vigny serano accompanied by Chopin. What silly nonsense. Too bad. H.B.

To Adèle, 12 May (CG no. 397, from Paris):

[…] I am writing to you from Alphonse’s place, where I dined with the Rocher family. I will hurry back to Montmartre, my poor Harriet is so unwell that she stayed on her own and I do not want to bother her to go out. Today she was better, may God wish that it lasts. By chance an English lady with several young children has come to the house where we live and she is of great help to Harriet.

Last Monday [5 May] we had a sort of little party in the countryside. My friends came to spend half a day at our place. They included celebrities from the world of music and poetry, Messrs. Alfred de Vigny, Antoni Deschamps, Liszt, Hiller and Chopin. We talked and discussed art, poetry, thought, music, drama, in short everything that constitutes life, in full view of this fine landscape and this Italian sunshine which we have been enjoying for the last few days. […]

To Humbert Ferrand, 15 or 16 May (CG no. 398, from Montmartre):

[…] In the meantime I have settled for a comic opera in two acts on Benvenuto Cellini, whose striking Memoirs you have probably read, the character of which provides me with a text that is excellent in several respects. […]

I have completed the first three parts of my new symphony with solo viola; I will now set out to complete the fourth. I believe it will be good and in particular strikingly picturesque in character. I have in mind to dedicate it to one of my friends you know well, M. Humbert Ferrand, if he will allow me. It has a March of pilgrims singing the evening prayer, which I hope will be famous in December. I do not know when this huge work will be published; at any rate, please see to it that M. Ferrand grants his authorisation. […]

To Humbert Ferrand, 31 August (CG no. 408, from Montmartre):

[…] I believe I told you that my symphony with solo viola, which is called Harold, has been finished for two months. I think Paganini will find that the viola part is not written sufficiently in the style of a concerto; it is a symphony on a new plan and not a composition written in order to display an individual talent such as his. But I still owe it to him that I have undertaken this work. At the moment the orchestral parts are being copied; it will be performed next November at the first concert I will be giving at the Conservatoire. […]

![]()

To his father, 6 May (CG no. 435, from Paris):

[…] We will shortly be going up to Montmartre to live in a delightful and inexpensive place. The garden is vast, the view over the plain of Saint-Denis is magnificent, and everything is cheaper than in Paris because we are exempted from import duties. […]

To his sister Adèle, 2 August (CG no. 439, from Montmartre):

[…] Harriet is very upset at seeing me thus reduced to slavery, all the more so as she cannot do anything herself. We were at one stage on the point of leaving for north America, but the uncertainty over what opportunities might be offered to her as well as Louis’ excessive youth held us back. In truth she is the one who is in need of courage, because after all I am busy, I am productive, I am active, I get dizzy. But her! all day long she is harassed by the servants who steal from us; the slightest upset of the child drives her to distraction. She was not made for the world around her where her own language is not even spoken, and is reduced to inactivity though conscious of her vast talent which could make us rich if circumstances were different. Her bouts of despair are understandable and all too justified. In a few years there will hardly be any theatre left in France, except for boulevard theatres; there are none left in England, and any actor of any merit in high poetic drama runs off to America. […]

To Humbert Ferrand, after 23 August (CG no. 440 [see vol. VIII], from Montmartre):

[…] I am working like a slave for four papers which provide me with my daily bread. They are le Rénovateur which pays badly, les Débats which pays well, le Monde Dramatique and la Gazette musicale which pay little. With all this I have to combat the horror of my musical position; I am unable to find time for composition. I have started a vast work called Fête musicale funèbre à la mémoire des hommes illustres de la France (Funeral celebration in music in memory of France’s famous men); I have already written two movements. Everything would have been finished long ago if I had had just one month to work on it exclusively; but I cannot afford a single day at the moment without running out of necessities shortly after. […]

To Adèle, 23 September (CG no. 409, from Montmartre; the letter belongs to 1835, not 1834):

[…] For a start, rest assured, our boy has been baptised. His name is not Hercules, Jean-Baptiste, Caesar, Alexander, or Magloire, but simply Louis. He does not scream at all during the day, but only at night, which his mother and nanny complain a little about. For my part I sleep peacefully in my room where I do not hear a thing but rest like a savage after his wife has given birth. The boy is charming, very strong, with superb blue eyes, a tiny dimple on the chin*, rather fiery blond hair as I had when a child, a little pointed cartilage on the ears as I have, and the lower part of the face somewhat short**. So much for the similarities with his father, but unfortunately he does not have any of his mother’s features. Harriet is absolutely mad about him. She has now made a good recovery; when I go to Paris she comes with her son and the nanny to wait for me half-way down the slope of Montmartre, in an alley lined with trees, where seven years ago I often came to contemplate Paris while dreaming of her. If we had both been told that in 1834 we would come and sit here as a family on these rocks…

Yesterday, while she was waiting for me, several English ladies happened to pass by; the nanny was a few steps away with the little one. These ladies came near to see the child which they found superb***. To all their questions in poor French Marie [the nanny] opened her eyes wide without understanding a word; Harriet listened with rapture to all their exclamations and comments, but could not restrain herself any more and answered in English, half laughing, half crying, that he was only five weeks old, that he was French and was born in Montmartre and that SHE WAS HER MOTHER. She was exploding with pride as she told me about it. It is the event of the day. […] In a week or so we will be in Paris, at no. 34 rue de Londres. We have rented an unfurnished flat, which at the end of the year works out much cheaper, though to begin with it involves some heavy expenditure: we have to buy furniture, wine, wood, and a thousand other trivia which you don’t think of in a furnished house. […]

[…] Early this morning Harriet and I went for a long walk in the plain of Saint-Denis and we talked about the young Prosper who is not afraid of open air, while watching the larks taking to flight around us. […]

* By order of his mother I am writing a note here to add that he has a very beautiful brow, which is true.

** Second note by order of the mother; he has a well-turned body, his limbs are wonderful.

*** Third order at Harriet’s command: many other French ladies and women from Montmartre have also stopped to admire Louis.

To his mother, 18 October (CG no. 445, from Paris):

[…] We are in a house which is not far from Paris, but getting there is rather hard work; you have to climb up one side of the mountain then go down the other. The view over the plain of Saint-Denis, with on the horizon the tombs of the kings of France, the hills of Saint-Germain, Montmorency, etc., is truly magnificent. And when Adèle said to me in one of her letters that she wished me open air, she was wishing for me what I have in abundance. Our garden is fairly large; the sitting-room of our flat was once a pavillion built by Henry IV for the charming Gabrielle. It is an interesting antique which we have partly restored in modern style. Despite the extreme fatigue caused to me by my visits to and from Paris we will keep this place for the winter. Apart from the site and the low cost, it has another advantage to offer in sheltering us from the chore of putting up with visitors; those who have nothing to do think twice before coming to pester me and waste my time.

From time to time my friends come to spend half a day at our place; recently for the anniversary of Louis’ birth [14 August] we had a brilliant gathering. The élite of the young counter-revolutionary writers, that is those who have shaken off the yoke of Victor Hugo, was present. We played the game of barres in the garden just like true schoolboys. […]

To Humbert Ferrand, 16 December (CG no. 453, from Montmartre):

[…] I have an opera that has been accepted by the Opéra; Duponchel is well disposed; the libretto, which this time will be a poem, is by Alfred de Vigny and Auguste Barbier. It is delightfully lively and colourful. I am unable as yet to work on the music, I am short of metal as is my hero (you probably already know that he is Benvenuto Cellini). […]

To Adèle, 24 December (CG no. 454, from Montmartre):

[…] Thank mother for her offer of a barrel of wine. We are not sure we will be staying much longer in Montmartre, and in any case the chore of getting the wine bottled, protecting it from robbers about whom we have a great deal to complain from every point of view, the cost of buying the bottles and paying for transport, all this reduces to almost nothing the advantage and saving to be made from this shipment. The jams on the other hand would be welcome; Louis likes them very much. This child is growing and rapidly becoming stronger; he does not speak at all as yet. But Harriet claims that when pointing to his dress he says very distinctly « Aunt » and I am instructed to tell this to you.

Farewell, tomorrow I have to rush around all day, and I have a dreadful headache caused by the smell of the coal which we burn. […]

![]()

To his mother, 4 January (CG no. 457, from Montmartre):

[…] The cold is dreadful this year, but it is particulary grievous in Montmartre. Besides, country houses such as the one where we live are ill-equipped for winter and we do not know how to keep the rooms warm. In spite of this we are fairly well, apart from myself who have been feeling rather uncomfortable for some time. Louis is growing and becoming stronger, but he is still not talking. […] We are very much on our own this winter; all the invitations we receive are useless, because of the distance and the near impossibility of coming by coach to our mountain. Besides these excursions are expensive and for this reason my poor wife always avoids them. And then it is not easy to separate her from her son for a whole evening, and you can hardly place any trust in the servants of Paris! The servants of Paris, there is a real scourge! You cannot imagine how dishonest, lazy and insolent they are. It is quite amazing. Harriet claims that it is worse since the July revolution [in 1830] and I think she is right. You are very lucky to have Monique. Besides they are very expensive, they demand coffee, etc., etc. We have changed them many times, but it is always the same thing; we have given up and keep those we have. […] If you could find at La Côte some good woman who would be suitable, perhaps the best course of action for us would be to get her to come here. […]

To Édouard Rocher, 23 January (CG no. 458, from Montmartre):

[…] We are alone here, in an isolated house, on the other side of the hill of Montmartre; in summer our friends come to visit us, but in winter the approaches are so strenuous that people prefer not to get stuck in the mud. We have a superb view over the plain of Saint-Denis and a large garden where our boy runs around, shouting and laughing with all his energy. […]

To his sister Nancy, 21 February (CG no. 464, from Montmartre):

[…] I am very happy to have the best and most loved wife in the world, but I am very upset at all the sacrifices I see her having to endure without complaining, at her isolation and especially at the loss of her immense talent (her enforced inactivity is killing her). There is no longer any great dramatic art in England, and art there is on the point of extinction. Here in Paris English theatre is dead and all attempts to revive it would be in vain. She has in her son an ever present consolation; but she is not easily reconciled to all the work I am obliged to do at home and in town, and which force me to leave her on her own. The servants are driving her to distraction. She hardly goes to Paris once every three months; but we are going there the day after tomorrow, for the first time since the middle of December. It is the first performance of Les Huguenots at the Opéra and Meyerbeer insists that she must not miss the occasion. Besides it will divert her a little. […]

To Auguste Brizeux, 22 April (CG no. 469, from Montmartre):

[…] Would you like to cause me a great pleasure? This would be to let me know the day you are able to come to Montmartre to spend an hour or two with me and meet Legouvé who is very anxious to meet you. […]

To his sister Adèle, 1 July (CG no. 474, from Montmartre):

[…] Our garden is magnificent, and you cannot get tired of the view over the plain of Saint-Denis; we recently went on foot to St Ouen and Louis was thrilled at the sight of the lake. There is nothing so beautiful in Dauphiné, except for the view of the valleys from the heights of the borders of Savoie. […]

![]()

Unless otherwise specified, all the photographs reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in June 2001 and June 2008, and other pictures have been scanned from paintings, photos, engravings, lithographs, prints, postcards and books in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

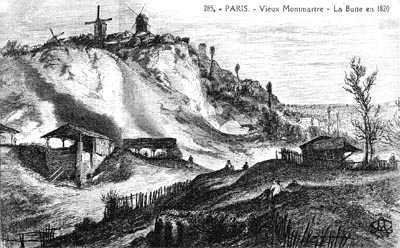

This postcard is a reproduction of an 1820 engraving.

This postcard is a reproduction of an 1820 engraving.

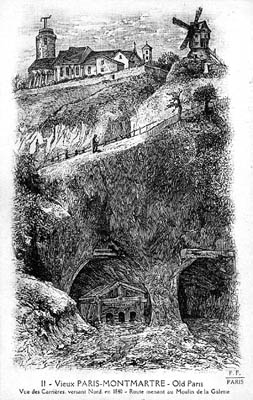

This postcard is a reproduction of an 1840 engraving, which shows the quarries on the north side of the slope.

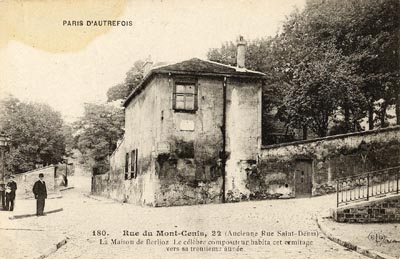

Two addresses are provided by Berlioz’s correspondence for the house in Montmartre. Letters of April and May 1834 give the address as no. 10 rue Saint-Denis (CG nos. 389, 392, 396, 399); Berlioz and Harriet stayed there until late September or early October when they moved back to Paris at no. 34 rue de Londres (CG nos. 409, 410). In May 1835 they returned to Montmartre where they stayed till September 1836 when they moved to 35 rue de Londres (CG no. 478-9), though Berlioz continued to use the Montmartre address till November (CG no. 482). Letters of 1835 and 1836 now regularly give the Montmartre address as no. 12 rue Saint-Denis (CG nos. 436, 437, 439, 441, 467, 468, 477). There is nothing in Berlioz’s extant letters to suggest that nos. 10 and 12 rue Saint-Denis were two different houses (the setting is described in identical terms throughout the period in Montmartre), and the evidence of engravings and paintings also suggests that the two addresses refer to one and the same house. The likelihood is that the number of the house was simply changed in the latter part of 1834: a letter definitely dated to September 1834 (because of its reference to Louis’ imminent christening) carries for the first time the address no. 12 rue Saint-Denis (CG no. 408ter, in vol. VIII).

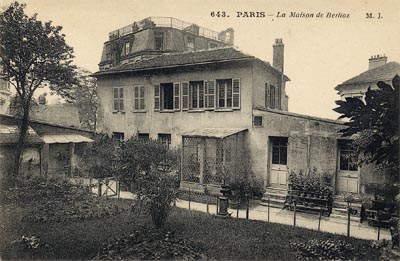

The original name of the street, rue Saint-Denis, was changed to the present one, rue du Mont-Cenis, in 1868. Berlioz’s house survived till the 1920s; several attempts were made in the early 20th century to preserve it and turn it into a Berlioz Museum, and though they failed they are worth recalling. In 1908 a group of Berlioz enthusiasts, among them Henri Martin the father of Jacques Barzun, created the Fondation Berlioz, whose first action was a pilgrimage to the composer’s house in Montmartre on 13 December 1908, the composer’s anniversary, to inaugurate a plaque which recalled Berlioz’s time in Montmartre. The pilgrimage became an annual event; for the year 1910 there are two accounts on this site of the pilgrimage of that year, one from Libre Parole for 12 December and the other from the Petit Journal for 13 December; both also mention for the first time the plan of turning the old house into a Berlioz Museum. A few years later, in 1919, the plan is mentioned again by Jean de Massougnes in the name of his father Georges de Massougnes, a Berlioz champion of long-standing who had recently died: he proposed the purchase of the house by public subscription for it to become a Berlioz Museum. Nothing happened immediately, but in 1922 Mlle Barbier, who had already purchased the house of Balzac and turned it into a museum devoted to the writer, now acquired as well Berlioz’s old house with the same purpose in mind. The story is told briefly in an article of Comœdia of August 4th, and at greater length in an article in Annales of 27 August, which mentioned how Mlle Barbier was threatened with expropriation by the state, and spoke up warmly for the preservation of a house so rich in historical associations. But in vain: the house was demolished in 1925 to make way for a large modern block of flats devoid of character.

The site of Berlioz’s house is now no. 22 at the junction of rue du Mont-Cenis and rue Saint-Vincent, and it bears a commemorative plaque. This plaque dates from 1984 and replaces the original plaque which was inaugurated in 1908. A number of medallions on the block of flats seem to be adapted from a XIXth C painting depicting the house in which Berlioz lived.

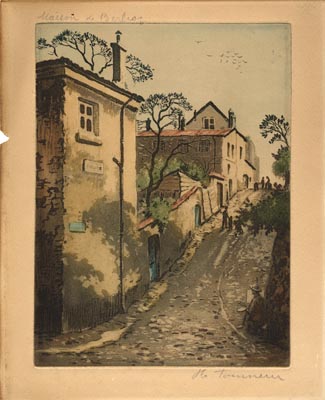

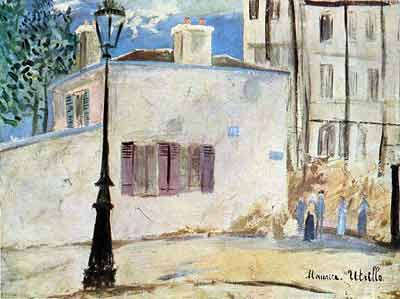

This painting by Sahut shows the house in which Berlioz lived in the mid-1830s as it was about 10 years earlier. The original painting is now in the Musée Hector-Berlioz at La Côte Saint-André.

We are most grateful to the Association nationale Hector Berlioz for granting us permission to reproduce the painting from Jean-Pierre Maassakker’s book, Berlioz à Paris, published by Association nationale Hector Berlioz in 1992.

We are most grateful to Mr. Kirst Hulspas for sending us an electronic copy of this drawing in his collection and granting us permission to reproduce it on this page.

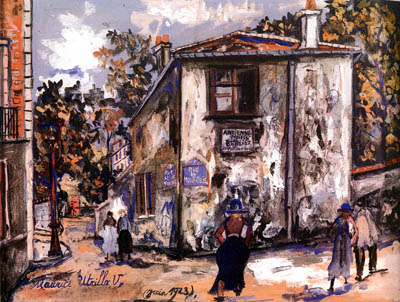

This very old lithograph is by Maurice Tourneur. The commemorative plaque below the window is visible on the wall; it was installed in 1908.

The above original photo dates from the 1920s.

We are most grateful to our friend Fumie Sakurai for sending us a printed reproduction of this painting.

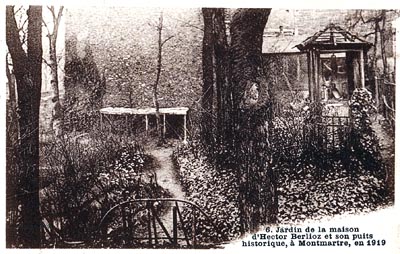

Berlioz entertained the elite of Parisian artistic and literary world in this garden, among them Chopin, Liszt, Hiller, de Vigny, Janin, Dumas and Deschamps (CG nos. 395, 396, 397).

A copy of this photo is in the Hector Berlioz Museum at La Côte Saint-André.

This is a reproduction of a painting by Utrillo on a postcard. Utrillo’s painting shows the wall on the left still standing.

The original of this unsigned painting (gouache on thick and cream paper) is in our collection. It is an imitation of Utrillo’s painting.

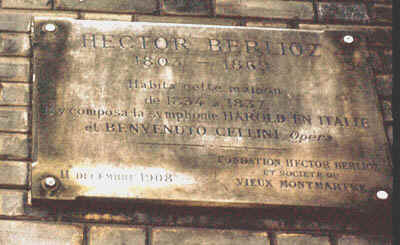

This plaque was originally installed in 1908 on the wall of Berlioz’s home, and was later reinstalled on the wall of the modern block of flats which replaced it (note that the date 1837 is incorrect and should be 1836). A new plaque later replaced this one in 1984.

This picture was sent to us by Mr John Winterbottom to whom we are most grateful.

This plaque dates from 1984 and replaces the original plaque of 1908. The plaque reads: ‘On this spot existed until 1926 a country cottage in which the composer Hector Berlioz lived from 1834 to 1836. He wrote there Harold in Italy and Benvenuto Cellini’. The latter statement is not quite accurate: the composition of Harold in Italy was started in January 1834 before the move to Montmartre, and Benvenuto Cellini was not completed till 1838, long after Berlioz had left Montmartre.

This medallion is derived from a painting by Sahut of the house as it was in 1825 (see above).

This view faces diagonally the site of the house of Berlioz.

The block of flats in the foreground on the right at the corner of rue du Mont-Cenis stands on the site of Berlioz’ home.

Nos. 11 and 11bis on rue Saint Vincent, which occupy the site of Berlioz’s home are on the right just off the picture (see next photo).

The building is on the corner of rue Saint Vincent and rue du Mont-Cenis (formerly rue Saint-Denis); the plaque which commemorates Berlioz’s home is on the right-hand corner of the picture (see the enlargement in the next photo).

The commemorative plaque is on the side of rue du Mont-Cenis on the wall of no. 22.

Compare this photo with Tourneur’s painting above, which shows rue du Mont-Cenis before the steps were built. No. 22 is the first block on the left of the picture.

![]()

The page Montmartre was created on 26 June 2001 and enlarged on 1 August 2009, 1 February 2014, and 1 July 2016.

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.