![]()

Introduction

The concerts of 1845

Selected letters

Journals

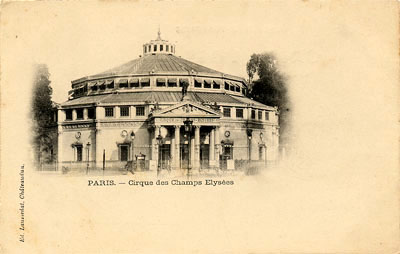

Cirque des Champs-Élysées

This page is also available in French

![]()

On 1 August 1844 Berlioz gave a large-scale concert for the Festival of Industry in a building which had been constructed specially for the purpose. The success of this venture encouraged the impresario Napoléon Gallois (1815-1874) to approach Berlioz some months later with a proposition for a series of large concerts, to be given in 1845 in the enclosed hippodrome off the Champs-Élysées of which he was director, the Cirque des Champs-Élysées, also known as the Cirque Olympique.

In his Memoirs (chapter 53), Berlioz gives a brief account of this venture (virtually the same account had been published by him before in the Monde Illustré no. 123, 20 August 1859, p. 122):

A few months after this trip to Nice [in September 1844], the director of the Franconi Theatre, enticed by the extraordinarily high receipts of the Festival of Industry, suggested to me that I should give a series of large-scale concerts in his Cirque des Champs-Élysées.

I do not recall what arrangements we made together for this purpose. All I know that it was bad business for him. Four concerts took place for which we had hired 500 musicians, and the expenditure involved in this number of players could not be completely covered by the receipts. Besides, the venue was once again unsuitable for music. The sound rolled around in this circular building with desperate slowness, and the result, for all the pieces that involved a certain amount of musical detail, was a most deplorable harmonic confusion. One piece alone made a great impression, the Dies Irae from my Requiem. The breadth of the tempo and of its chords made it less inappropriate than any other in this vast building that reverberates like a church. The success it scored obliged us to include it in the programme of every one of the concerts.

This undertaking did not earn me any money and was excessively tiring.

This summary account is supplemented by a number of contemporary sources: letters of Berlioz to various correspondents dating from November 1844 onwards, a selection of which is reproduced in translation below, and articles in various journals, notably a presentation of the forthcoming series of concerts published by Berlioz himself in a feuilleton in the Journal des Débats of 29 December 1844, and several announcements and reviews published by the weekly musical journal Le Ménestrel. A selection of these articles is reproduced in translation below, and the full French text will be found in the French version of this page. There is also a review of the first concert which appeared in L’Illustration on 25 January 1845, and which is reproduced on a separate page in the original French and in English translation. All translations are © Michel Austin.

The project was probably decided around the end of October 1844: it is first mentioned in a letter of 5 November (CG no. 924), by which date Berlioz was already actively involved in preparations. Considerable expense was lavished by the manager of the hippodrome in adapting it to its new purpose as a concert venue and making it comfortable in winter. Though large audiences were expected the concerts were aimed in practice at the well-to among the Parisian public, as Berlioz admitted in a letter (CG no. 925): whereas in August 1844 the seats were priced at 10 fr., 5 fr. and 3 fr., in 1845 only the two higher prices were available (Le Ménestrel, 12 January; 9 February). One wonders whether the organisers wanted to reassure the authorities and avoid the risk of politically-inspired disturbances such as nearly broke out at the concert the previous summer. By excluding the less affluent the concerts of 1845 were therefore different in spirit from the Concerts populaires introduced years later by Jules Pasdeloup in 1861. The initiative in the enterprise came not from Berlioz, as in 1844, but from Gallois, the director of the Cirque. All the same the numerous press reports show that the concerts were associated in the public mind with Berlioz himself.

Preparations for the concerts involved considerable exertion for Berlioz, as his correspondence shows (CG nos. 926, 938, 943, 955). Players and singers had to be recruited and rehearsed (CG nos. 930, 942, 946, 948, 953bis), and programmes selected with the assistance of the composers (CG nos. 925, 927, 950, 951). Much attention was devoted to publicity: before the start of the series Berlioz used part of one feuilleton to introduce the concerts to the Paris public and stress the attractions of the newly embellished venue (Journal des Débats, 29 December 1844; CM V pp. 616-18). Numerous letters show him writing to sympathetic critics and editors to publish announcements and secure a favourable press (CG nos. 934, 935, 936, 937 for the first concert). A special effort was made for the third concert, at which the total number of performers was raised to 500 (CG nos. 945, 946, 946bis, 946ter, 946quarter, 947). Invitations were sent to members of the aristocracy to add lustre to the occasion (CG no. 949, 949bis). As often Berlioz’s reliable copyist Roquemont was of invaluable help behind the scenes in getting ready the quantities of parts needed (CG nos. 951, 954, 959).

No firm decision was made at the start on the total number or indeed the dates of the concerts. In the event four concerts were given between January and April, though more had been envisaged: ten days after the last concert Berlioz was still considering the possibility of a fifth one at the end of the month (CG no. 957), though in the event it did not take place. Le Ménestrel gives the full programme of the first three concerts, which took place on 19 January, 16 February, and 16 March respectively. The final concert on 6 April included (in Part I) Weber’s Freischütz overture, the Offertorium from the Requiem, an aria from Louise Bertin’s Esmeralda, the second movement of Harold in Italy, the Dies irae and Tuba mirum from the Requiem, (in Part II) the first and last movement of Félicien David’s Nonetto (first performance), a Cavatina and Rondo from Glinka’s Life for the Czar, the Queen Mab scherzo from Romeo and Juliet, and Berlioz’s orchestration of Leopold von Meyer’s Marche marocaine (first performance).

Music by Berlioz figured in all four concerts. His new overture La Tour de Nice, which he had started composing in Nice in September 1844 and finished in the autumn (CG no. 924), was coolly received, as contemporary reviews suggest (L’Illustration, 25 January; Le Ménestrel, 26 January), and Berlioz set it aside for revision: it became later the overture Le Corsaire. But this setback was counterbalanced by the general success of his other pieces, and most strikingly the Dies irae and Tuba mirum of the Requiem, which by popular demand had to be repeated exceptionally at all four concerts (CG nos. 934, 937, 942, 943, 968, and the reviews of the first three concerts).

Among other composers Berlioz characteristically promoted (in his first concert) music by his idol Gluck, though it does not appear to have made the impact he had hoped (Le Ménestrel, 26 January). Among contemporaries he made a point of including music by Glinka at his third and fourth concert: he had recently met the Russian composer who was visiting Paris in 1844-1845, was favourably impressed by him and devoted part of a feuilleton to introducing him to French audiences (Journal des Débats, 16 April 1845). Other initiatives of Berlioz were more obviously designed to appeal to the tastes of the Paris audience. This applies to his promotion of the Austrian virtuoso pianist Leopold von Meyer, who created a sensation at the second concert and took Paris by storm. Berlioz commented on his success in a feuilleton shortly after: ‘As for the Moroccan March […] to say that it was encored in the vast hall of the Cirque, that it electrified and swept away this immense audience whose attention, it was believed, could only be held by large masses of sound, is to acknowledge in it a most extraordinary power to impress when played by its author’ (Journal des Débats, 4 March [CM VI, p. 14]; cf. 16 April). Berlioz was encouraged to orchestrate the Marche marocaine which he presented at the end of his fourth concert, with great success (Le Ménestrel, 13 April). He played it again later in the year in Vienna (CG no. 1006; 23 November), and a third time at a concert at the Théâtre Italien in Paris on 9 May 1846. Berlioz’s orchestration was published in Vienna in the same year. The success of the orchestration of the Marche marocaine induced Berlioz to orchestrate as well in 1845 another piano march by Meyer, his Marche d’Isly, though in the event he did not perform it himself and it was not published in his lifetime.

Of particular interest are the relations of Berlioz with the composer Félicien David (1810-1876). Like Berlioz a pupil of Lesueur at the Conservatoire, David had suddenly shot to fame through a performance of his ode-symphony Le Désert at the Conservatoire on 8 December 1844. The work appealed to the contemporary fashion for Orientalism; it became instantly popular with audiences in France and remained a favourite for decades to come (it was performed in Lyon in April 1845 where Berlioz’s sister Adèle heard it and was moved — CG no. 957). Berlioz decided to try to secure performance of the new work for his series of concerts and approached David directly and through friends (CG no. 927) — David was a follower of Saint-Simon and had numerous supporters in the circle of Saint-Simon’s adherents — and he published without delay a highly eulogistic article on David (Journal des Débats, 15 December 1844; CM V, pp. 597-607). Le Désert was in the event performed complete and with great success at the second concert on 16 February (CG no. 943; Le Ménestrel, 23 February). Berlioz also included two movements from David’s new Nonetto at his last concert (CG nos. 950, 951, 958, 959, 967). He performed Le Désert again at the concert on 9 May 1846 at which he performed Meyer’s March marocaine for the third time. But in time Berlioz may have come to regret the rather exaggerated praise he had initially lavished on David, and his article of December 1844 should be compared with a much more measured review by Edmond Viel in Le Ménestrel not long after (5 January 1845): this review reads almost like a rebuke to Berlioz for not having been more critical, as well as for failing to point out David’s debt to Berlioz himself. Berlioz’s later reviews of subsequent works or concerts by David are noticeably tepid in comparison (Journal des Débats 27 November 1851; 12 March 1859; 7 April 1861; 23 May and 23 December 1862). In the account of his visit to Marseille in June 1845 which he published in 1848 Berlioz made a light-hearted reference to Le Désert, which had been performed there shortly before his visit. In his private letters he pulled no punches on David’s limitations (CG nos. 1034, 2029, 2283, 2368, 2855). It is perhaps ironical that David was later to succeed Berlioz both at the Institut and as Librarian of the Conservatoire.

Despite initially high expectations and Berlioz’s best efforts, the series as a whole was no more than a qualified success: the early concerts had to contend with adverse weather conditions (CG no. 943; Le Ménestrel 26 January, 23 February), expenses were very high because of the large number of performers involved (CG no. 955), and, as in 1844, despite his initial optimism Berlioz conceded later that the acoustic conditions of the large hall were not favourable. The series terminated after the fourth concert, probably earlier than anticipated; it is known from one of his letters that his uncle Marmion, who had been kept informed of the undertaking (cf. CG no. 943), attended the concert. Berlioz’s letter to his sister Adèle after that concert strikes a dejected note (CG no. 957), and in the end he and the director of the Cirque had little to show for all their efforts.

![]()

CG = Correspondance Genérale (8 volumes, 1972-2003)

To his sister Nancy (CG no. 924, 5 November):

[…] I have been unable to reply to you these last few days, as I have not had a moment of peace on my own. I have had articles to write, a quantity of pieces of music to compose and I am far from having finished. I have written a large-scale overture for my forthcoming concerts [La Tour de Nice], I am writing the music specified by Shakespeare for Hamlet which is being staged at the Odéon in a verse translation by Léon de Wailly. I must complete within a fortnight a small collection of pieces for the melodium-organ which were commissioned from me by the maker of this new instrument. You can see that I have a great deal to do. At the same time I have had to run around to find a flat, and to recruit step by step the personnel for my concerts at the Cirque etc. […]

To Giacomo Meyerbeer (CG no. 925, 12 November):

I am busy at the moment organising several large music festivals which will take place this winter at the hippodrome of the Champs-Elysées; the director (M. Gallois) will spend what is necessary to embellish and heat the hall, and the prices will be fairly high so that the audience will consist solely of the elegant and better-off part of the Paris public. I will devote all my attention to the performances. There will be a chorus of 150 voices and an orchestra of 150 musicians. The two Préfets are very favourably disposed to this undertaking. If you think it suitable, I would love to perform in one of these concerts an excerpt from your new opera [Ein Feldlager in Schlesien], which presumably is now being performed in Berlin. Is there a large piece (particularly a chorus) which could be performed on its own without losing too much by not being staged? […]

To his sister Nancy (CG no. 926, 30 November):

[…] I am writing to you in a rush before getting back into a coach. I am preparing my first musical festival at the Cirque, I am at a loss where to turn next, I have so many horses to ride all at once. […]

To Émile Barrault (CG no. 927, 12 December):

I went twice to see David at home, and wrote to him to ask whether it would be convenient for him to have his symphony [Le Désert] performed at one of my large concerts at the Cirque. He has not replied. Could you find out what this means? If he has another more promising project in hand, so much the better. Otherwise I would need to have his agreement at once, as I am obliged to fix and prepare my programmes well in advance. […]

To J.-L. Heugel [the Editor of Le Ménestrel] (CG no. 929, ca. 24 December):

Here is the programme with one small change; please include it on Sunday [sc. in Le Ménestrel] with a few words of praise on the magnificence of the hall, its sonority, the grandeur of the performance, etc… just a harmless little puff… […]

See Le Ménestrel of 29 December 1844 and 12 January 1845.

To Eugénie Garcià (CG no. 930, 26 December):

I thank you for your gracious offer to sing a new piece of my composition, but I do not have anything that is brilliant or suitable for a concert such as the one I am organising. I think therefore that if you would like to sing the Inflammatus from Rossini’s Stabat mater this would benefit the programme; besides I could easily obtain the orchestral parts as they have been printed. […]<

To Théophile Gautier (CG no. 934, 4 January):

Gallois [Napoléon Gallois, the director of the Cirque Olympique] told me that he had recommended to you our musical festivities at the Cirque, and I am writing to you to recommend them once more. Please write half a column in your feuilleton on Monday dwelling on the magnificence of these solemn occasions, on the hall, on the heating, on the lighting, on the drapery, on the carpets, on the shrubs, the 350 musicians, the second act of Orphée: The Elysian Fields and Tartarus, the excerpts from my Requiem, my new overture The Tower of Nice. In short pull out all the stops, full steam ahead, bring in the ladies’dresses that will be visible down to their knees, etc., etc. […]

To Jules Lovy (CG no. 937, 9 January):

Be kind enough to announce in Le Tintamarre or Le Tamtam my concerts at the Cirque.

The first will take place on Sunday 19th at 2 o’clock. The hall will be splendidly decorated, illuminated and heated; there will be 350 performers; Ponchard, Mme Eugénie Garcia, Haumann, Hallé, an excerpt from Gluck’s Alceste, the second act of his Orphée, an excerpt from Piccini’s Atys, a concerto by Beethoven [the 5th in E flat], plus a new overture I have composed, as well as the Roman Carnival overture, three excerpts from my Requiem and the Hymn to France. […]

To Gustave Boutry-Boissonade (CG no. 938, 1 February):

[…] At the moment I am living like a wounded and bloodied wolf, alone in the depth of the woods; the enforced labour of my concerts can hardly rouse me from my sombre inertia, and I behave like someone sleep-walking. […]

To Michel-Maurice Lévy (CG no. 942, 16 February):

I went to see you a few days ago to ask you a favour which means a great deal to me. Tell me frankly whether it is possible to obtain it. It involves asking on my behalf and yours your best students to sing two pieces at my third concert, which will take place in the Cirque des Champs-Élysées in a month. I only want to include them in the Tuba mirum of my Requiem (not a difficult piece), and in the oath of reconciliation of the Capulets and Montagues in my Romeo and Juliet symphony. If these gentlemen would accept a small fee, I believe that despite the enormous expenses it might be possible to give it to them. […]

To his uncle Félix Marmion (CG no. 943, 20 February):

I should have replied to you sooner, but you can probably imagine that these great devilish concerts are giving me a lot of trouble. The second took place last Sunday with dazzling success: the performance, the music, the layout of the orchestra and of the hall, etc. were all applauded by five or six thousand hands. The receipts were all the more gratifying as there was half a foot of sleet and slush in the Champs-Élysées. Hence if the sun smiles on us we can expect a full hall on every occasion. If this happens I will have organised a fine institution. The major expenses have been covered now. My net profit only amounts to 1000 francs, but the next concerts will cost half less and will bring in more.

You cannot imagine the tremendous impact made in this vast hall by the Dies irae of my Requiem; I have just performed it for a second time and will have to repeat it for a third time. I have a little orchestra which includes 50 violins, 20 violas, 20 cellos and 15 double-basses, together with double or triple wind, and in addition a chorus of 300 voices.

All this worked with wonderful ensemble last Sunday, and we performed the symphony Le Désert by Félicien David in a manner that buried completely the Théâtre Italien which has performed it several times. […]

To Théophile Gautier (CG no. 946quater [vol. VIII], early March):

Please find a way of announcing my concert in your feuilleton on Monday, I will be extremely obliged.

Among other things mention that the enthusiasm of the performers at the last concert was contagious, and that a large number of professional and amateur musicians and choristers asked to sing in the chorus, with the result that the total number of performers will now reach five hundred. […]

To Queen Marie-Amélie (CG no. 949, 12 March):

Allow me to submit to Your Majesty the programme of the third music festival I am giving at the Cirque des Champs-Élysées next Sunday. These great artistic occasions seem to be arousing every day ever more public support, but their success can only be complete if they manage to earn the interest of Your Majesty. Forgive me, Madam, for the liberty I am taking in requesting the honour of your presence for this coming occasion. Such a favour would be a powerful encouragement for all the musicians and for myself. […]

To Robert Griepenkerl (CG no. 955, late March-early April):

[…] Since I received your last letter, I have undertaken a large-scale musical project: a series of concerts with 500 performers in the hippodrome of the Champs-Élysées, the largest and finest hall in Paris. But it lies almost outside the city, and if there is any mud the takings can be grievously affected. Hence every concert is a source of new worries, as the expenses are immense (6000 frs.). I am giving the fourth in a few days. It would give me great pleasure, or rather happiness, to see you here, especially during these dreadful rehearsals which are extremely stressful. The fact is these concerts give me much more trouble than all those which came before, and this is the reason: the best players in my normal orchestra are members of the Conservatoire orchestra, and this famous society prevents them, for the whole duration of the concert season, from taking part… [the end is missing]

To his sister Adèle (CG no. 957, 16 April):

[…] As for David, I forgive you for having been moved by his music, but instead of going to the trouble, your husband and yourself, of queuing at the Grand Théâtre [in Lyon], why did it not occur to you to drop him a line to inform him that you are my sister and that you wanted to hear Le Désert? He would immediately have sent you tickets for a box and would have come to thank you.

He is a decent fellow, rather nonchalant, straightforward and dignified, but his conversation is no more scintillating than his personality, though you would have been very happy to meet him. One cannot always think of everything.

I believe I have now finished my concerts at the Cirque; I may give a fifth and final one at the end of the month. Here we have up to six concerts a day, and you cannot walk a step without seeing another one advertised that is even more far-fetched than the previous ones. I am inviting my porter to give his own concert as well… All of this is depressing, the public is obsessed, exhausted and ruined. Thalberg has given up doing his second soirée; the Ministry is studying ways of building a dam against this deluge of cacophony. […]

To his sister Nancy (CG no. 968, 6 June):

[…] I would have liked to let you hear at my last concert at the Cirque my Dies Irae, and I believe you would have been shaking for two full hours at least. But it seems that you will never hear any of the music I have composed. […]

To Joseph d’Ortigue (CG no. 1034, 16 April, from Prague; cf. CG no. 1028):

[…] The details you provide on David’s unfortunate experience made me shudder, and the article by Duchesne in the Journal des Débats [24 March] was terrible in its cold impartiality. But then what an idea to undertake the ascent of Mt Sinai when you are short of breath, and to want to carry the tablets of the law when you do not have a strong arm!… This subject was quite unsuitable for him. I make the same recommendation to you as you addressed to me in your last letter: do not say that I wrote anything about this to you. […]

To his sister Adèle (CG no. 2029, 30 September; cf. CG no. 2032):

[…] I do not know yet whether I will pick up the courage to undertake some musical enterprise in Paris before my departure. Félicien David tried to present his Désert and his Christopher Columbus to the large crowds which encumber Paris at the moment. He obtained the hall of the Conservatoire and lost 2000 francs [14 September]. His music is now thought to be childish… Ah! Time is a great teacher! I am not sure whether the champions of this style of pale music will be able to withstand the teachings of that master,

And rekindle the torch of extinguished David [a citation from Racine, Athalie].[…]

To his sister Adèle (CG no. 2283, 11 March):

[…] This morning I am in a state of stupor. We came back last night at one in the morning amidst dreadful snow and slush, after enduring at the Théâtre-Lyrique the revival of La Perle du Brésil, an opera by poor Félicien David in which he provided a curious specimen of silly music, which he confuses with simple music. All the ex-followers of Saint-Simon were there, and gave him a grotesque ovation. The story is as flat as is the score. […]

To his son Louis (CG no. 2855, 3 or 4 May; cf. CG no. 2850):

[…] … You know that La Captive by F. David has been withdrawn by the authors in agreement with Carvalho; the work seemed too pitiful indeed and they did not dare risk a performance. It appears that platitude must not be taken too far. This example of an opera withdrawn voluntarily before the performance because of its platitude is unique. […]

![]()

See the French version of this page for several concert announcements in the journal Le Ménestrel that are not included here.

Journal des Débats, 29 December (p. 2)

MUSIC FESTIVAL

at the Cirque des Champs-Élysées.

It is on the 19th of next month that we propose to inaugurate the new hall which is destined for great musical occasions. If I refer to this hall as new, it is not because it is the first time that it will be laid out to serve as a concert hall. For a long time the opinion of professional musicians has identified it as the only venue in Paris where it was possible to bring together, in good acoustic conditions, imposing masses of voices and instruments. Yet for a long time all attempts to secure the hall have failed against the set determination of the director not to put it to any other use than that for which it was built. But at long last the administration has modified its view that anything but equestrian exercises would be fatal to the future of the Cirque, and it took itself the initiative to welcome music and invite it to settle there. But extensive works were required to change into a winter venue a building which hitherto had only been opened to the crowds during fine summer days. Several heating installations have been put in place, and the various openings of the upper part of the building have been tightly closed so as to allow inside a temperature as high as can be desired. Although concerts will take place during the day, the circus, amphitheatre, corridors and foyer will all be splendidly lit up with gas. The layout for musical performances will be as follows:

A floor built on the arena of the hippodrome will accommodate the orchestra and nothing else. The orchestral players will thus occupy the whole of the circus, the central point of the building, from which the sound will radiate in every direction and spread equally to the mass of the audience. On one side of this horizontal surface there will be a small platform destined for the soloists, the conductor, and on occasion a small chorus of twelve to fifteen voices. On the opposite side and facing the platform, the main chorus will rise in an amphitheatre on a section of the tiers which used to be occupied by the public. In front of these tiers will stand the chorus masters, who will keep an eye on the conductor and convey to the singers the beat and the tempi. The special feature of this arrangement is that the solo singers, several feet above the instruments, will be separated from the chorus by the entire width of the orchestra, and will face the choristers directly instead of being behind them, as is the case in all the theatres where large-scale concerts have taken place. The advantage of this arrangement will be seen particularly in compositions such as Gluck’s Orphée, where a single figure dialogues with the chorus. The celebrated No of the infernal gods, in the scene in Hell, cannot fail to gain in power and terror. The same will apply to the symphony Romeo and Juliet which I hope to perform there. The small chorus of the prologue which tells the story of Shakespeare’s drama will not be integrated with the two choruses of the Capulets and Montagues, as it inevitably was in the hall of the Conservatoire, and Friar Lawrence will be able to give much more force to his admonitions by addressing them directly. The number of performers will not exceed 350, and each group will be rehearsed separately, before the general rehearsal, following the method which we adopted last July for the Festival of Industry. This number is dictated by the shape and capacity of the Cirque, in which a chorus of 200 voices is more than adequate to produce a very powerful effect. As for the orchestra, it fills up the hippodrome to such an extent that it would be impossible to increase it by even three or four musicians. We go into these details to answer the daily and sometimes very insistent representations on the part of those singers and orchestral players who have not been included on the list of performers. This is not a musical congress, and the success of the undertaking of August 1st last cannot oblige us to assemble on every occasion a body of a thousand to twelve hundred musicians.

What we wish and have every good reason to hope for are grand and excellent performances of fine works that are little known to the Parisians, and occasions that are truly worthy to have been given the name of musical festivals. The beauty and sonority of this vast modern circus, the comfort which the audience will find there, the talent and devotion of the artists to whom the performances have been entrusted, our own efforts to conduct them well, and the ever more remarkable love of the public for great music: these are the chances of success which we have taken into account in this undertaking, and on which it may not be too presumptuous to count.

Despite the abundance and variety of the programmes each session should only last two and a half hours at most. They will take place on Sundays, once or twice a month, and starting at two o’clock will therefore end at half past four.

H. BERLIOZ.

L’Illustration, 25 January (first concert)

Le Ménestrel, 26 January (first concert)

Berlioz is a truly infernal creature! You can see him staring intently all round the vast Cirque des Champs-Élysées, where a battalion of little devils placed under his command seem to be holding session! On one side you can see trumpets and Sax bugles, on the other timpani and bass drums, everywhere violins and cellos, then at the extremities and arranged in a girdle these immense double-basses, and at the centre the flutes, oboes, horns, bassoons, clarinets and other supporting instruments… They look like a fantastic and numberless army, belching forth their missiles with feverish zeal. On top of all these instrumental masses there is a no less formidable legion of singers, divided in four sections on the facing terraces.

Berlioz revels in the midst of all this. Each note, each stroke of the bow goes straight to his heart; that is his life, his element, his religion. If you remove from his hands this magic baton, the man falls lifeless to the ground, as you have deprived him of his raison d’être.

And yet Berlioz has experienced gentler times. Berlioz used to play the guitar!!… … So strange is the world we live in. You can see that in music even the extremes are able to agree and find common ground. Some fifteen years ago Berlioz, the fiery composer of symphonies, was no less than a soft-hearted and elegiac minstrel. But now even the sound of a guitar would hardly dare to reach his ears; but the time will come when the writer of symphonies, renouncing Satan and his trombones will pick up again his old forsaken lute to sing with a sigh of his first loves. — The reader may laugh at this horoscope, but stranger transformations have been witnessed. — But in the meantime Berlioz wants to pursue his calling and lay firm foundations for his glory. And it is to promote once more this goal that he has summoned his musical battalions; in answer to his call, the hippodrome of the Champs-Elysées has metamorphosed into a concert hall.

The uncertain seasonal weather, and perhaps too the high price of the seats, had admittedly left a few gaps in the front rows, but everywhere else there was an abundant crowd, and the spectacle was imposing to behold. The programme contained some fine items, notably the Tuba mirum from Berlioz’s Requiem, which electrified the audience: it was arresting, grandiose and sublime.

The new overture The Tower of Nice was not so successful; but the Hymne to France brought back again the bravos from the entire audience. — The vast scene of Hell by Gluck was little understood, and consequently coldly received, and without the attractive singing of Ponchard, which brought old Orpheus back to life, the assembled Cirque would have cast a shroud over this magnificent piece without further ado. Indeed, Mme Eugénie Garcia, all dressed in black, seemed to have already resigned herself to the loss. A few fine vocal flourishes on her part were not able to overcome the general indifference. To sing and love Gluck, you need to have pondered and lived with him for a long time. And then you would require choral masses that are less dull: there was a crowd of people there who had been paid to sing but who ought to have paid to be allowed to do so. This criticism is directed particularly at the tenors. More flabby voices and a greater uncertainty of intonation can hardly be imagined. From this point of view amends need to be made in a most emphatic way.

The concerto by Beethoven was wonderfully played by M. Hallé. As for the violinist Haumann he scored a double success. After playing his introduction, then giving a delicious rendering of the Song of Guido, his bow stopped abruptly: the hair had miraculously become completely detached, like the wings of Giselle breaking on contact with the earth. — It was as though Haumann’s bow was refusing to play the piece’s finale, written in a skipping and coquettish style that jars with the charm and elevation of the melodies of Guido. But this did not prevent the celebrated artist from picking up again a bow complete with hair and rounding off his solo to great applause.

On leaving this first festival at the Champs-Élysées, the large audience was greeted with a less than welcome surprise. Thick clouds had gathered over the Cirque and torrential rain threatened the unfortunate pedestrians. And to cap this misfortune the hordes of cabs which clutter the streets of Paris had deserted the vicinity of the concert and kept a diabolical distance from the normal stops and junctions. The number of dinner parties, of missed meetings and parties that failed to materialise, which afflicted the capital on this Sunday must have been incalculable!…

Discomforts of this kind cannot be repeated at the second festival, as every precaution will be taken against the vagaries of the weather, and an immense file of cabs and buses will spread out at the doors of the Cirque to bring back the crowds of dilettantes to every quarter of Paris. Add to that a most interesting programme, among which is the Romeo and Juliet symphony and two ounces of Félicien David.

A vast balcony, placed above the choristers and facing the orchestra, had been reserved for the royal family, which was unable to take part in this festival.

Le Ménestrel, 23 February (second concert)

The winter which is bearing down hard on us shows no more mercy to M. Berlioz’s music festivals, and were he not a seasoned fighter it would certainly be possible to count the number of empty seats at the Cirque des Champs-Elysées.

Despite the heavy blanket of snow which last Sunday obstructed the approaches to this hall a rather large crowd had gathered for Berlioz’s second festival. So Félicien David’s ode [Le Désert] did not preach in the desert. Besides, this was not the only attractive element in the programme. The overture to Les Francs-Juges and the Dies irae came first, and literally created a furore. A Moroccan march performed in a rather bizarre way by M. [Leopold de] Meyer demonstrated once again that he is the most agile and fastest of all pianists. Applause did not fail M. Meyer and was then transferred to Le Désert. It was like a new test: at first M. Félicien David’s brow seemed to indicate anxiety on his part at the sight of these 350 performers and this immense hall, but the grace, simplicity and melodic charm of the work overcame once more the obstacles presented by such a large theatre. The success was complete. The Sunrise was unanimously encored. The public was particularly taken with the personality, voice and talent, somewhat Arab in character, of M. Béford. The Evening rêverie, interpreted by this mysterious singer, acquires for us Parisians an oriental colour, which might be something quite different, but which charms and electrifies us and transports us to the sands of the Nile. M. Félicien David ought to tell us whether M. Béford does have an Arab voice or not, for it would be disagreeable to be left in doubt on this point.

As for the song of the Muezzin it is always less effective, yet M. Béford sings it in pure Arabic, and makes a fairly good job of it, if we are to believe the African chieftains who attended the first performance of Le Désert at the Théâtre Italien.

Le Ménestrel, 23 March (third concert)

Last Sunday the posters were announcing two fine matinée concerts. Hence a great dilemma for our Parisian dilettanti: how was it possible to be simultaneously at the Cirque for the concert of M. Berlioz, and at Salle Herz, in answer to the call from M. Dorus? On one side 500 performers led by their formidable conductor, and on the other the delightful voices of Mme Dorus-Gras, Géraldy, Ponchard, and the bewitching flute of the beneficiary. The magnificent Tuba mirum of Berlioz was summoning us to the sound of trombones to the Champs-Élysées, but the flute of Dorus, like a true Siren, was enticing us to rue de la Victoire. Of all times this was the moment to toss a coin over the two concerts. The matinée of Dorus fell to our lot, and our faithful colleague made his way with resignation towards the Champs-Élysées. […]

On leaving Salle Herz, we met our faithful colleague who was beaming on his return from the Cirque des Champs-Élysées.

Berlioz’s concert had attracted a fairly large audience, in spite of the heavens which have never ceased to manifest their hostility to the Cirque. But in fact the occasion was altogether remarkable, as could be guessed from the programme which we published last Sunday.

Schnetzoeffer’s overture to Le Spectre, which came at the start of the programme, contains fine orchestral effects, but seems to us to suffer from a certain diffuseness, and perhaps also from noise. The experiment with Russian music which was carried out that day was favourably received; Mme Solowiowa was very successful in the great aria from the opera A Life for the Czar by Glinka, which she sang in Russian. The first part of this aria has really individual colour and character, though the rondo reverts completely to Italian forms, and as for the dance movements, they have remarkable and perhaps excessive originality. They contain a passage in triple time, rather like a waltz theme, which is delightfully effective.

The Tuba mirum by Berlioz, a magnificent inspiration, electrified once more the whole audience. The excerpts from the Romeo and Juliet symphony, that is the Ball scene, the Scene in the garden, the Queen Mab scherzo and the finale, also made a great impression, though M. Laget, who was singing the part of Friar Lawrence in the finale and who had asked for the public to show indulgence, was unable to perform his task satisfactorily. The concert ended delightfully with Weber’s Invitation to the Dance, an exquisite composition which Berlioz has orchestrated so well.

Le Ménestrel, 13 April (fourth concert)

[…] It remains for us to speak of the Conservatoire and of M. Berlioz, these pillars of great music, these representatives of the highest school — I was about to say of the old guard. The Conservatoire is announcing its ninth session, and last Sunday Berlioz made his farewell to the Cirque des Champs-Elysées. For this session he had orchestrated the celebrated Moroccan March of Meyer. The success was overwhelming. General instructions had to be sent to Marshal Bugeaud to propagate this march in Algeria through our military bands. This should make it possible to subdue all the peoples of Africa, Bedouins, Arabs, Kabylians and others. — Messrs. Berlioz and Leopold [de] Meyer each deserve an honorific Yatagan.

![]()

The Cirque des Champs-Élysées in which Berlioz conducted his four concerts in 1845 was initially called the Cirque de l’Impératrice and was built in stone in 1841 according to a design by the architect Jacques Hittorfs; it was demolished around 1899-1900. It was also variously referred to as the Cirque d’été, the Cirque d’été des Champs-Élysées, and the Cirque Olympique.

This engraving appeared on page 325 of the 25 January 1845 issue of L’Illustration, a copy of which is in our collection; the picture was accompanied by a review of the concert. Note the bearded Bedouin on the left of the picture, and see also the cartoon in Le Charivari of 18 January 1845 (the day before the concert!) showing a group of Algerian chieftains blocking their ears at this concert.

This 19th century photo is in our collection.

This postcard is from our collection.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page. All rights of reproduction reserved.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.