By

Pierre-René Serna

© 2005 Pierre-René Serna

Translated by Michel Austin

© 2005 Michel Austin

This page is also available in French

![]()

In composing les Troyens in the mid 19th century Berlioz was going against prevailing fashions. This is the time of the triumph of French historically-based grand opera, as shown by Auber, Halévy or Meyerbeer. Subjects drawn from classical antiquity, which till the end of the previous century had been the principal source for operatic works, were no longer anything more than an object of derision: Offenbach was to turn this to good advantage. Gounod’s Sapho of 1851 was an exception, hence its failure but also the enthusiasm with which Berlioz greeted the work. The same is true of French literature, and the dramas of Hugo and Dumas ignored classical mythology, its gods and epic stories, on which Corneille and Racine had drawn. With les Martyrs Chateaubriand was one of the first novelists to choose an ancient subject, but only to justify it with an edifying final tableau on the triumph of Christianity. Gautier’s le Roman de la momie [The Story of the Mummy] is quite different in this respect: this was the first large-scale work of fiction to raise without apology the banner of a return to Antiquity. Written in a sober style, devoid of psychological undercurrents but rich in descriptions that are almost archaeological in their meticulous precision, the book tells of the fate of the beautiful queen Tahoser who ruled in Egypt in the 12th century B.C. and fell in love with a Hebrew who had departed to follow the exodus of his people. At the time of publication the novel had little success and there were few echoes of it in the press. But it is unlikely that Berlioz was unaware of this work by a close friend, even though no references to it are to be found in his writings; his correspondence has survived in an inevitably fragmentary form, yet the work was likely to arouse in him at least as much interest as he felt for Sapho1.

Let us compare dates. Le Roman de la momie was published in book-form by Hachette in April 1858, though it had previously been serialised in le Moniteur universel between 11 March and 6 May 1857. The libretto of les Troyens was composed between April and June 1856, and the first phase in the composition of the opera, in which the libretto underwent a number of changes, extended from August 1856 to April 1858. Gautier’s novel appeared therefore during the period when Les Troyens was taking shape. Given the frequent contacts between the writer and the composer, one may even conjecture that the latter might have had access to the sketches of a novel that was also started in 1856 and whose subject was likely to attract him. It may even be that his attention was drawn to the documentation that Gautier acknowledged he used for his work, in particular the Histoire des usages funèbres et des sépultures des peuples anciens [History of the funeral customs and burial practices of ancient peoples] by Ernest Feydeau which appeared in 1856.

Among artistic and literary sources that are usually cited for les Troyens, apart from Virgil and Shakespeare, La Fontaine is occasionally mentioned, together with the painter Guérin, or even Euripides and the Persian poet Hafiz2. But le Roman de la momie is never mentioned, except by Ian Kemp, though only as an accidental parallel3. One might imagine that commentators on les Troyens, the majority of them admittedly English-speaking, had never even looked at Gautier’s book! Indeed, anyone who is familiar with Berlioz’s masterpiece and reads the novel can hardly fail to be struck at once by the remarkable similarities or echoes of it that may be found in the opera.

SIMILARITIES BETWEEN THE TWO WORKS

Let us start with the observation that ancient Egypt is indeed present in Act IV of les Troyens in the whole of the divertissement which consists of a ballet and the aria of Iopas. ‘Almahs’ and ‘Nubians’ are a way of describing traditional dancing girls and a people of ancient Egypt. As for the “Theban harp player”4 wearing an “Egyptian religious costume” who accompanies Iopas, as a stage instruction specifies, he owes his name to Thebes, the capital of the Pharaohs. Let us note also the letter of 25 February 1857 in which Berlioz outlines his intentions concerning the ballet by referring to a “dance step of Almahs” and “singing Almahs”, which probably means the first and last elements of the danced triptych, while alluding to “dancers from Egypt who had previously come from the Indies”5. In its first version, where the “Dance of the slaves” is as yet missing6, the ballet seems thus to owe its colouring exclusively to Egypt.7

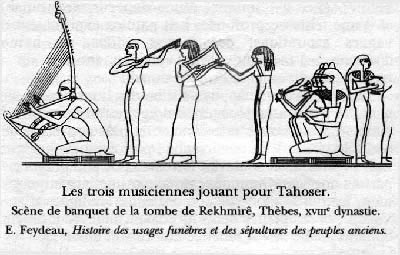

Let us now turn to the Roman de la momie. On page 90 and following8, Tahoser listens to a divertissement with music and dance. Three women players are present: “a young woman beating time on a tympanon”9, another one who “plays a kind of mandora” (an instrument related to the lyre) and “a harp player who sings a mournful strain, accompanied in unison”. Tahoser interrupts the musicians a first time alleging that “her soul is weeping through the music”. A livelier song follows during which “women started to dance”. But once more they are unable to engage the attention of Tahoser who says she is “sad”, and therefore all the women “withdrew”. It is hardly necessary to recall the similar scene, a spectacle within a spectacle, which similarly fails to engage Dido in Act IV of the opera.

Shortly after (page 95 and following), Nofré, the confidante of Tahoser, debates at length with Tahoser in the following words: “Why are you sad and unhappy, Mistress? Are you not young and beautiful (…).” To which Tahoser replies: “An unsatisfied longing makes the rich person as poor in his golden palace (…).” At which “Nofré smiled and said in tones of disguised mocking: (…) Loneliness feeds gloomy thoughts. From the top of his war chariot, Amhosis will cast a graceful smile at you, and you will return to your palace feeling happier.

– Amhosis loves me, Tahoser replied, but I do not love him.

– These are the words of a young virgin, Nofré retorted (…).”

Here the duet between Anna and Dido is irresistibly brought to mind by this passage in the novel.

To continue. Starting on page 112 a great ceremonial procession is described, involving “music played by drums, tambourines, trumpets and sistrums”. Further on (page 141), there is mention of games displaying the “prowess of two fighters, whose left arm was equipped with a boxing-leather [ceste, from the Latin caestus]”. This time it is hard not to think of the “March and Hymn” followed by the “Boxing fight [Combat de Ceste] – dance step of wrestlers”, in the first Act.

Elsewhere, on page 156, a woman singer accompanied by a “mandora” is instructed: “Sing me some ancient song, that is very soft, tender and slow”. The way Dido invites Iopas to sing his verses seems here to lie just below the surface.

On page 171 a solemn procession of farmers passes slowly in front of the landlord; a note by the editor comments on the “spectacle that is intended to be both beautiful and religious”, in the same way as the “Entry of the farm-workers” in Act III of the opera. Imitating Dido, the landlord who is so honoured comments: “Agriculture is sacred; she is the mother who nurtures man”.

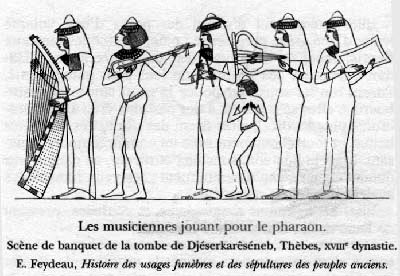

Other similarly striking echoes may be noted, as on pages 139 and 140, three successive dances by slaves accompanied by “sistrums”, “cymbals”, “clarions”, a “harp” and a “double-flute”, or on page 161, the description of Tahoser “who wishes through music to calm the storm in her heart”.

Among the many descriptions in which the novel indulges, there is also that of numerous musical instruments, such as harps, lyres, mandoras (several times), tambourines and other percussion instruments, cymbals (page 161), sistrums (pages 112, 114 and 140), and a double flute (page 139). All these references cannot fail to recall the “antique” instruments which les Troyens introduces: “antique double-flutes”, sistrums, small antique cymbals, triangles or the tarbuka, without omitting the lyre and harp which accompany Cassandra and Iopas on stage.

These echoes, doubtless not accidental, relate to moments in the opera which the libretto could not derive solely from the Aeneid, with the exception of the duet between Anna and Dido. There is a good reason for this, since these concern essentially music (the ballets or “Entries”, the instruments) or a non-narrative song like the aria of Iopas. This explains how Berlioz may have sought to supplement his inspiration, certainly in the present case of Gautier’s novel, and perhaps also with other sources (such as the book by Feydeau cited earlier10) that were outside Virgil11.

GAUTIER AND LES TROYENS

But doubts may also arise. In a letter dated 29 or 30 June 1856, that is only a few days after the completion of his text, Berlioz mentions “several people who have allowed me to read to them my work here.” On 21 August he adds: “The poem of les Troyens is clearly enjoying considerable success.” Readings were also to take place at the house of baron Taylor in February 1857 and in March at Bertin’s, the director of the Journal des débats, in the presence of columnists and journalists (such as Gautier). The libretto was thus beginning to circulate in Paris. Admittedly this affected only a select audience, but Gautier may have been of their number. In any case it was difficult for him to be unaware of a project which had become known in the literary and artistic circles of Paris. And if the musician sought advice or suggestions from his friends, the writer may, on an ancient theme, similarly have moved close to his colleague for some situations in his work. Hence a possible reverse influence from the librettist on the novelist, or at the very least a convergence of reciprocal influences12.

It should however be noted that Gautier seems to have been remarkably indifferent at the time of the performances of les Troyens à Carthage. Yet by this date both artists had moved apart, after Gautier’s intervention late in 1857 in favour of Tannhäuser13. This may also explain the silence of both men on the subject we are dealing with.

Pierre-René Serna

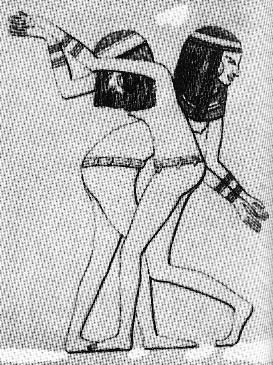

Source: Wilkinson, J G, 1837, The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. London: John Murray; referred to by Ian Kemp in les Troyens, Cambridge Opera Handbooks.![]()

Source: Wilkinson, J G, 1837, The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. London: John Murray.![]()

Source: Wilkinson, J G, 1837, The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. London: John Murray.![]()

_____________________

Notes

1. Le Roman de la momie is an acknowledged precursor of Flaubert’s Salammbô (1862), which, as is conclusively established, deeply impressed Berlioz. It is as a consequence of his enthusiasm that the musician turned to the writer for advice on the costumes for the performances of his Troyens à Carthage. Flaubert had himself declared his enthusiasm for the subject of his Carthaginian novel, which was so opposed to the bourgeois habits and “modern lifestyle”, for which he felt nothing but “disgust”, of his Madame Bovary or his Éducation sentimentale (see Flaubert’s letter of 29 novembre 1859, and also the letters of 24 April 1852, 30 October 1856, 11 February 1857, 23 January 1858, and 26 May 1863). And yet posterity has

chosen to remember these last two works of Flaubert, against the verdict of the author himself, and in preference to Salammbô which Berlioz had the insight to single out. In the same way posterity once chose the Symphonie fantastique and la Damnation to the detriment of les Troyens.![]()

2. See the Introduction by Hugh Macdonald for the Bärenreiter edition.![]()

3. Les Troyens, Cambridge Opera Handbooks, page 198.![]()

4. The “Theban harp” is found already in the “Trio for two flutes and harp, performed by the young Ishmaelites” in l’Enfance

du Christ.![]()

5. See also the commentary by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on the ballet in les Troyens on this site; they cite les Soirées de l’orchestre and the description there of a ballet and music performed by Indian players in London in 1851.![]()

6. The final version of the ballet in its present form dates from 1859.![]()

7. Ancient Egypt was also at the heart of one of Berlioz’s last operatic projects: Antoine et Cléopâtre after Shakespeare, as shown by the letters to Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein dated 28 October, 7 November, 2 and 13 December 1859. It seems that this was a way of rounding off his musical career by returning to the roots of the cantata Cléopâtre of 1829, which was already dedicated to Shakespeare.![]()

8. References are to the pocket French edition “Livre de poche”, in the series “Classiques de poche”. It is easily accessible and currently available, and in addition is provided with a commentary and illustrations which can only support the argument developed here.![]()

9. As Gautier specifies, this is a percussion instrument “built of a wooden frame slightly bent inwards and over which the hide of an onager is stretched”.![]()

10. It has been possible to draw up a definite list of the works on Egyptology that were in Gautier’s possession, among which is to be found in particular The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians by J. G. Wilkinson, which appeared in 1837. The list is reproduced on page 255 of the edition in the Livre de poche series.![]()

11. The Aeneid remains nevertheless the fundamental source, and it also names the antique instruments (double flute, sistrum) and other objects used in les Troyens, such as the boxing-leather [ceste].![]()

12. My friend Michel Austin thus makes the judicious observation, in connection with the “Combat de ceste” (Boxing fight) in Berlioz and Gautier, that a computer search of Virgil’s text for the Latin word caestus – a kind of leather glove loaded with balls of lead – shows 9 uses of the word by the poet. No less than 8 of these are in the book of the Aeneid (V) which concerns the funeral games held by Aeneas (and always in the context of a fighting match: lines 69, 379, 401, 410, 420, 424, 479, 484), while there is only one example in the Georgics (III.20). It seems therefore very likely that Berlioz borrowed the idea of the boxing fight directly from Virgil, whose work he knew so well. The same might be true of Gautier. What other sources outside Virgil could Gautier have drawn on?![]()

13. See the article by Gautier in Le Moniteur of 29 September 1857, and also the letter of Berlioz to Adolphe Samuel of 27 December 1857. Subsequently, during the performances of Tannhäuser at the Paris Opéra in 1861, Gautier was to prove an ardent champion of Wagner and the rift with Berlioz was then complete.![]()

![]()

We are most grateful to our friends Pierre-René Serna for sending us this article and Olivier Teitgen who provided the illustrations. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 20 February 2005. Revised on 1 November 2023.