![]()

Introduction

The first visit: April-May 1831

The second visit: September 1844

The third visit: March 1868

Nice in pictures: Nice in times past Berlioz’s Nice in our time

This page is also available in French

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.

![]()

Nice held a very special place in Berlioz’s affections because of the special circumstances which attended his first stay there in April-May 1831. He had arrived in Rome in March but the lack of news from his fiancée Camille Moke in Paris drove him to distraction and induced him to leave Rome on 1 April to return to Florence. After waiting two weeks there he received a letter from Camille Moke’s mother informing him that the engagement was broken and that her daughter was now going to marry the rich piano-manufacturer Camille Pleyel. Berlioz decided there and then to return to Paris to exact revenge by murdering all three culprits… On his way there he passed through Genoa where he attempted to commit suicide, but wiser counsels prevailed; he stopped instead in Nice where he spent a month from ca. 19-20 April to 21 May. He later gave a light-hearted account of the episode in his Voyage en Italie in 1844, which was substantially reproduced in his posthumous Memoirs (chapter 34), though there is no doubt that at the time the insult had hurt him deeply. In the event the stay in Nice was a turning point in his life; he was able to start his recovery, and he later remembered this period as the happiest three weeks in his life. Nice became forever associated in his mind with happy memories, which he frequently recalls in his later writings. He returned there twice, the first time in September 1844 where he stayed for several weeks, and the second time near the end of his life, in March 1868, when the visit this time had tragic consequences from which he never fully recovered.

It was almost by chance that Berlioz stopped in Nice: his first thought had been to return to France via Turin, but the Italian police refused him a passport and told him to go via Nice instead (Nice at the time was part of the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, and only reverted to France in 1860). This was a stroke of good fortune: he was immediately seduced by the town, its location and surroundings, and besides the proximity of France meant that he could be in close correspondence with his family at La Côte-Saint-André. Shortly after his arrival he wrote to them at length (CG no. 219, 21 April):

[…] I have rented a lovely room with an old lady; I am on a small fortified mountain, my windows open out on the sea; my fellow-lodgers in the house are two young men from Arles, to whom my good lady introduced me this morning.

Here is the address: H.B c/o Widow Pical, Clerici house, consulate of Naples, at the Ponchettes, Nice-Maritime. […]

Nice is a really fresh and pink-coloured city, the sea, the mountains, everything is green. I am so near you that the trip to Lyon costs only 62 francs, and everybody speaks French. […]

It was from his stay in Nice that Berlioz’s love for the sea dates. A long letter addressed to a group of friends in Paris gives a detailed account of his arrival in Italy and subsequent events up to his stay in Nice (CG no. 223, 6 May, from Nice):

[…] I have a delightful room with windows overlooking the sea. I have got used to the continuous moan of the waves. When I open my window in the morning, it is wonderful to watch the crests approaching like the undulating mane of a squadron of white horses. I go to sleep to the sound of the breaking waves which crash against the rock on which my house is built.

The location of Nice makes it a really delightful little town; the sea and mountains are fresh and pink-coloured. Occasionally, and at the risk of breaking my limbs, I go for excursions among the rocks. The other day I discovered the ruins of a tower built on the edge of the precipice; there is a small open space in front of it, where I lie down in the sun and look out at sea watching ships arriving from afar, I count the fishermen’s boats and marvel at that golden path of rays which, according to Thomas Moore, must lead to some bright isle of rest!* Actually it is in real life the subject of the lithograph of our melodies; yes, Gounet, it is exactly that. […]

* Note: this is a quotation from Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies, from the poem entitled How dear to me the hour (London, 2nd ed. 1822, p. 27). The full poem reads:

How dear to me the hour when day-light dies,

And sunbeams melt along the silent sea,

For then sweet dreams of other days arise,

And memory breathes her vesper sigh to thee.

And, as I watch the line of light, that plays

Along the smooth wave tow’rd the burning west,

I long to tread that golden path of rays,

And think ’twould lead to some bright isle of rest!

But Berlioz did far more than just contemplate the sea and go for walks: the circumstances of the stay in Nice stimulated a burst of composing activity. On arriving there he hinted at his intentions (CG no. 219, 21 April, to his family):

[…] I am going to undertake an immense work; I must not waste my time and get lost in dreams; what I fear above all is letting tender feelings and memories of happiness flood back. By showing to myself a way forward I will forget the past. […]

My young and sublime orchestra, so we will meet again!… We have great things to do together. There is a musical America there, Beethoven was its Columbus, I shall be Pizarro or Cortez. […]

Very quickly he settled down to a concrete project. While waiting in Florence for news from Camille Moke he had read for the first time Shakespeare’s King Lear: within a few days of arriving in Nice he started an overture on the subject which was completed within less than three weeks (CG nos. 222, 223, 225), after which he started a second overture (Rob Roy) which was completed a few weeks later, and also a new work of an autobiographical character (the Mélologue, later called Lélio) which combined spoken narrative with separate pieces of music (CG nos. 228, 231). His stay in Nice was prolonged for longer than he had initially anticipated; eventually he departed for Rome on 21st May via Genoa and Florence, and on the return journey continued to work on the Mélologue which was eventually completed in Rome (CG no. 230).

Berlioz never forgot the happy times he had spent in Nice in idyllic circumstances. Subsequently in periods of stress his thoughts would often turn back to those moments. In a letter to General Lvov in St Petersburg in January 1848 he writes ‘You are asking me where I intend to spend the summer; I do not know. I may possibly go to visit Nice again, as I always do when I have had a tough winter’ (CG no. 1170). By this time Berlioz had already made a return visit to Nice, in September 1844: during the summer he had organised and conducted (1 August) a vast concert on the occasion of the Festival of Industry, and was advised by his friend Amussat the doctor to go and spend time there to recover from the stress this had induced. Unlike the first stay in 1831 no letters survive from this visit in September 1844, though it evidently rekindled his affection for Nice, as may be seen from a reference in one of his feuilletons two months later (Journal des Débats, 10 December 1844). From the account in the Memoirs (chapter 53, previously published in Le Monde Illustré on 13 February 1858), the stay in September 1844 was comparable to the earlier visit. But while his first stay had been largely centred on Nice, this time he ventured further along the coast:

It was with deep emotion that I revisited the places where I had been thirteen years earlier, during another and different convalescence, at the start of my stay in Italy… I swam a great deal in the sea and made many excursions to the vicinity of Nice, Villefranche, Beaulieu, Cimiez, and the Lighthouse. I resumed my exploration of the rocks along the coast where I found, still slumbering in the sun, familiar old cannons. I saw again fresh and inviting bays, clad with sea-weeds, where I used to bathe. The room where in 1831 I had written the overture to King Lear was occupied by an English family, so I set up my quarters in a tower leaning against the rock of the Ponchettes, above the house.

I thoroughly enjoyed the wonderful view over the Mediterranean and the tranquillity which seemed to me more priceless than ever. Then, after eventually recovering from my jaundice and using up my 800 francs, I left this delightful coast of Sardinia which has always had such a strong attraction for me, and I returned to Paris to resume my thankless labours.

Berlioz does not mention here that, as in the previous visit, he composed another overture: it was originally called, appropriately, La Tour de Nice [The Tower of Nice] and first performed at a concert the following year; the work was subsequently revised between 1846 and 1851 and renamed Le Corsaire. The tower in Nice (which he called the Tour des Ponchettes) had special personal associations for Berlioz: when in 1860 Nice was eventually attached again to France he greeted the event in one of his feuilletons in the Journal des Débats (26 June): ‘Ah! my dear Tour des Ponchettes, where I spent so many sweet hours, from the top of which I sent so often my morning greetings to the slumbering sea before the sun would rise, you are trembling with joy on your rocky foundations, you feel happy to be a French tower!’

Over the years, Berlioz continues to mention Nice from time to time in his correspondence, always with fond memories and the expressed wish of being able to return there. To his sister Adèle in 1857 (CG no. 2254, 12 October):

[…] I am very sorry to hear what you are telling me about my uncle’s health; I cannot believe that the climate of Nice does not agree with him; how is that possible? It is the most gentle and pure air that you can breathe. Ah! how I wish I could go there. […]

To his son Louis in 1864 (CG no. 2839, 1 March; cf. no. 2945):

[…] I was feeling much better since I had taken the decision not to write any more feuilletons. By cutting down on expenses I can manage without the income they brought in. But I would need to go to Nice to cure my throat ailment which is getting worse, and I cannot. […]

To his uncle Marmion in 1867 (CG no. 3227, 12 March):

Your letter caused me a great deal of pleasure; I shared in the joy you are experiencing of living quietly by the sea in this adorable city of Nice; if I was able to I would gladly come and keep you company. I have already been there twice; I stayed in the district of the Ponchettes. On the first occasion I was living at the Clerici house, and on the second in the tower which is above and against the rock. That is where I wrote (though did not compose – I would always compose by the sea), my overture to King Lear, some thirty five years ago now. Alas! Alas! it is still a youthful work but its author is rather old. […]

During his last concert tour abroad, in winter 1867-1868 in Russia, one thought which kept surfacing in his letters was his wish to escape from the rigours of the Russian winter and enjoy once more the balmy sunshine of Nice and Monaco (CG nos. 3319, 3327, 3330, 3334). Back in Paris after his trip he wrote to Vladimir Stasov (CG no. 3346, 1 March 1868):

I have not written to you since I have been back, I was suffering so dreadfully. Today I am a little better; I send you my greetings with the news that I am leaving for Monaco. I will depart this evening at 7 o’clock. I do not know why I am not dying. This being so, I will go and see again by beloved coastline of Nice, the rocks of Villefranche and the sunshine in Monaco. […]

But this time everything went terribly wrong. The first letter to tell of his two successive falls, in Monaco around 6 March and the next day in Nice where he suffered a stroke, is addressed to Josef Derffel after his return to Paris (CG no. 3347, 19 March):

As we had agreed, I wrote to you a few days after returning from St Petersburg. Since then I have been to Monaco and Nice where I experienced nothing but disappointments and accidents. I first fell in the rocks at Monaco, where I damaged my face; it is a miracle that I did not kill myself. Then another fall in Nice where I stayed eight days in bed.

Since my return here I stay in bed all the time, and besides I have no wish to show myself, as my looks are not presentable. But my features are beginning to recover their shape. […]

The first full account was given by Berlioz to Estelle Fornier several days later (CG no. 3348, 25 March):

I am writing to you instead of paying you a visit. I am in bed in Paris. I stayed eight days in bed in Nice. It is very odd, the trip I made was absurd. My niece knows nothing about this, neither does my brother-in-law, in Grenoble they know nothing either, but I cannot let you remain ignorant of my accident any longer.

So let me tell you that I was feeling bored in Monaco for two days when one morning I wanted to get to the sea down some dangerously steep rocks. After three steps my rashness was obvious, I was unable to keep my foothold and fell headlong on my face. I stayed on the ground alone for a long time, unable to get up and streaming with blood. Finally, after quarter of an hour, I managed to drag myself to the villa where I was washed and bandaged willy-nilly.

I had reserved a seat in the omnibus to return to Nice and went back there the next day, but listen to this. Having reached Nice, though all disfigured, I wanted to see the terrace overlooking the sea which I used to be so fond of, and went up there. I sat on a bench, but as I could not get a good view of the sea, I stood up to change place, and hardly had I walked three steps that I fell straight, again on my face, and shed more blood than the day before. Two young men who were walking around on the terrace came in alarm to pick me up and took me by the arms to the Hôtel des Étrangers, not far from where I had fallen. I stayed in bed motionless for eight days, and when I had enough strength I came back to Paris without worrying about how I looked in the railway. My mother-in-law and my servant screamed when they saw me come in. Since then I have not left my bed, and for two weeks I have been in agony without getting better. My nose and eyes are in a sorry state; the doctor, to console me, said I was lucky to have shed so much blood, otherwise I would have expired there and then, particularly on the second day. […]

A number of letters over the next few weeks give similar accounts of the two incidents (CG nos. 3350, 3356, 3360; CG no. 3349 specifies that Berlioz’s fall in Nice was the result of a stroke). A letter to the Grand-Duchess of Russia, dated 14 April and which Berlioz took two days to write (CG no. 3363), adds some further details (CG no. 3354; cf. 3364):

[…] M. Becker [the secretary to the Grand-Duchess] also informs me that you like to hear my own account of the two falls I suffered and which the newspapers have mentioned since my return from Russia.

I had gone to Monaco to find a little sunshine. I found none, and one morning, after booking a seat on the omnibus for Nice, I went for an excursion in the rocks near the sea; I was thinking of going down to an inaccessible spot. I had hardly made a few steps when I felt dragged by the slope, lost my balance and realised that I could not control myself. I fell headlong on my face, lost consciousness almost completely and remained prostrate shedding quantities of blood. Workmen who were busy on a railway line below heard my fall but could not come to my rescue. A few minutes later I managed with great difficulty to return to the Hôtel de Paris, where I was washed and went to bed.

The next day I wanted to take advantage of the omnibus to Nice, and despite my disfigured face I boarded it for the return journey. The trip took four hours. Hardly had I arrived that I felt like revisiting the terrace to which I had been so attached, near the Hôtel des Etrangers where I had gone. My fall in Monaco had probably shaken me badly; all I was trying to do was to find a spot which would give me a better view of the sea, and without even tripping over I fell on my face like the day before, only even more heavily. Two young men who were passing by, alarmed by my fall, came to pick me up. They escorted me to the hotel still covered in blood and helped me get into bed. I stayed there motionless for eight days, after which I asked to be taken to the station. That is how I returned to Paris without seeing a doctor. The doctor I finally saw kept me in bed and is still insisting that I stay there. He assures me that I am lucky to have lost so much blood, otherwise I would have remained on the spot for good. Now I can begin to breathe and there are days when I am much better. […]

In fact Berlioz never fully recovered from the combined effects of the fall and the stroke, and he died just over a year after they had happened.

![]()

Unless otherwise specified, all the pictures on this page have been scanned from engravings, postcards and other publications in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

For the history of the locations depicted below we have drawn on a number of publications, including Promenade des Anglais, Nice 1833-1933 (published in the 1930s), Nice d’Antan (HC Editions, 2005), a visitors guide entitled Musée Masséna, and Nice, La tour Bellanda, a document published by the Centre du Patrimoine in Nice.

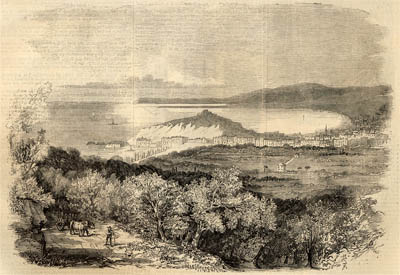

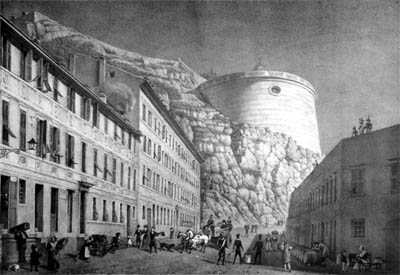

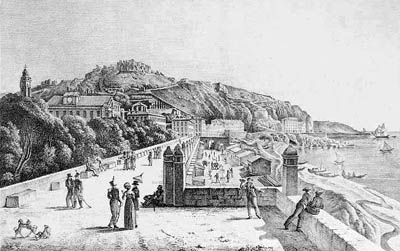

The original of the above painting by Hippolyte Caïs de Pierlas (1787-1868) is in the Masséna Museum.

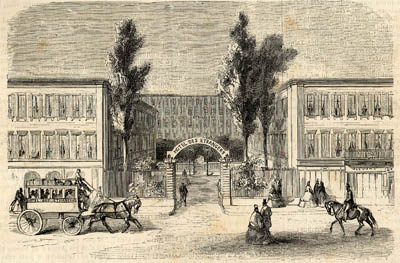

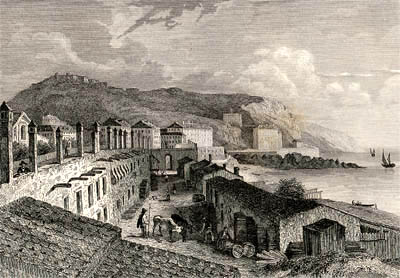

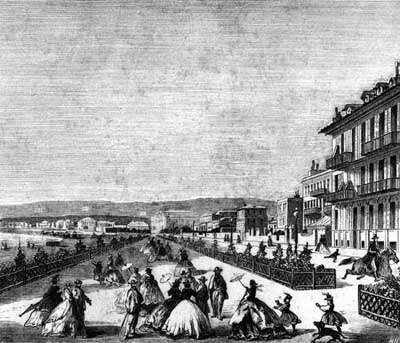

The above engraving was published in The Illustrated London News on 18 December 1858.

The above engraving was published in The Illustrated London News on 18 December 1858.

1831 – Maison Clerissi at the foot of the Tour Bellanda [Bellanda Tower]

1844 – Tour Bellanda

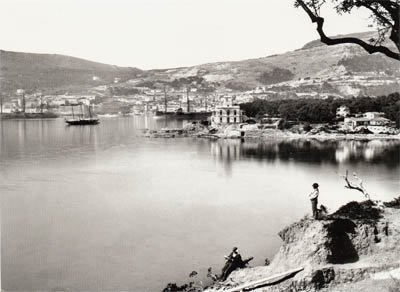

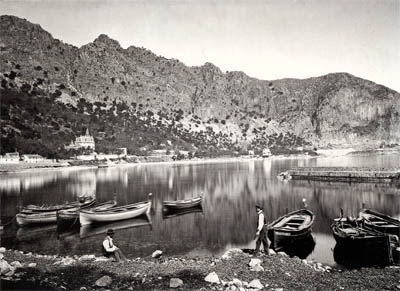

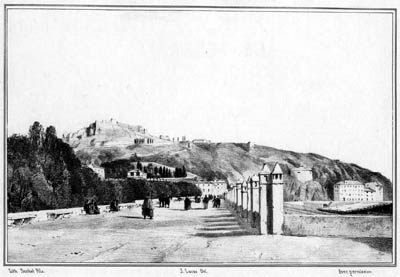

The Bellanda Tower overlooks the Rue des Ponchettes, which in turn gets its name from the small fishermen houses which were known as the Ponchettes. It is probably for this reason that Berlioz in his letters, in the Soirées de l’Orchestre, and in his feuilleton of 1860 refers to the tower as the Tour des Ponchettes [Ponchettes Tower].

The origin of the tower goes back to the 15th century construction of a wall as a defence system around the upper town and its château on the hill (now called Colline du Château) which overlooks the sea and the low town, the present Old Nice. The tower was initially called Tour du Môle; it was renamed Tour Saint-Elme in the 17th century, Saint Elme being the patron-saint of sailors. In 1705 Louis XIV took the town and its fort and had the château and the town’s wall completely destroyed in 1706.

At the foot of Tour Saint-Elme, of which only the base had survived, a certain Clerissi built a house. In 1824 Onorato Clerissi obtained the concession for the ruins of the tower, and built on them an imposing tower covered with a terraced roof with a panoramic view of the surrounding area. The tower was named Tour Clerissi after a visit by the king of Sardinia, Charles Félix in the winter of 1826-1827. In the tower rooms were built which would complement the pension installed in Maison Clerissi. (Note that in his letter of 21 April 1831 Berlioz spells Clerissi as Clerici; the text on a plaque commemorating the reconstruction in 1825 of what became known as the Bellanda Tower spells it as Cléricy.)

The tower has changed ownership many times. One of the later proprietors of the reconstructed tower renamed it Bellanda in 1850-1860, after another tower, much more set back, which formed a different part of the original 15th century fortification wall and was called Bellanda Tower.

In 1866 the tower and the adjoining land were bought by Jean-Édouard Hug, a Suisse hotelier, who had already purchased in 1856 the old Maison Clerissi in which he had established the Hôtel and Pension Suisse.

The Tower became more accessible by the construction in 1888 of the Lesage Steps, named after Jean-Charles Lesage, a benefactor of the City of Nice who left a legacy of 50,000 francs to make the château, where the tower is situated, more attractive.

Berlioz stayed in the Maison Clerissi during his first visit to Nice in 1831, and in the tower in his second visit in 1844 (CG no. 3227). A plaque on the tower commemorates his 1844 visit.

In 1924 an annex of 60 rooms was opened near the tower.

Before the Second World War there was a plan to open a Berlioz Museum in the tower, but by the 1950s the idea had been abandoned for lack of available documents. In the event, a Naval Museum was inaugurated in the tower on 1 June 1963, which was eventually closed on 1 December 2002. After a complete refurbishment by the City of Nice the tower was opened to the public in the summer of 2010 with an exhibition of works by the great Niçois painter Charles Martin-Sauvagio (1881-1962).

The Tower to the right of the picture and nearest to the sea is what used to be called Tour du Môle and then Tour Saint-Elme, later Tour Clerissi after the reconstruction of 1825 and later still Bellanda Tower.

A copy of the above engraving, designed by Gio Ludovico Baldoino, is in the Archives départementales des Alpes-Maritimes, Nice. The above image has been scanned from a leaflet published by the Centre du Patrimoine, Nice.

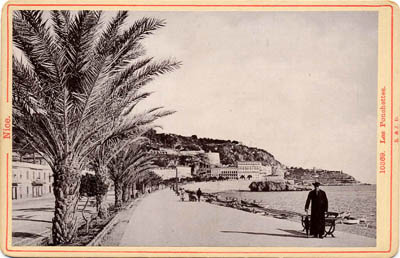

The above engraving is scanned from Promenade des Anglais, Nice 1833-1933. The road which leads to Bellanda Tower (see below) is now in the old town of Nice, lined with beautiful old flat-roofed houses and art galleries.

The above photo shows a lithograph by Paul-Emile Barbéri, a copy of which is in the Masséna Museum in Nice. The road which leads to the tower is the Rue des Ponchettes.

The photograph was taken by Michel Austin with the Museum’s permission.

The above oil on canvas painting, reproduced on a postcard, and entitled “Pêcheurs tirant leurs filets sur le bord de mer aux Ponchettes” [Fishermen dragging their net by the sea at the Ponchettes], is by the Niçois painter Ercole Trachel (1820-1872). The original painting is in the Masséna Museum.

This photo of Bellanda Tower is scanned from Promenade des Anglais, Nice 1833-1933.

The above engraving was published in L’Illustration in 1863. The horse-drawn omnibus to the left of the engraving bears the name of the hotel and may have been for the exclusive use of the guests who stayed at the hotel.

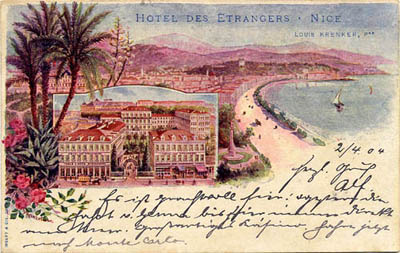

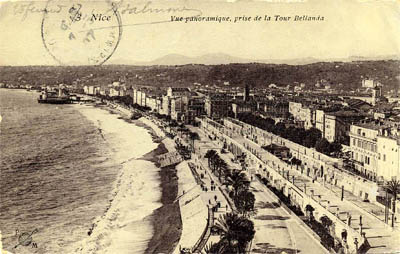

The above card was posted on 2 April 1904.

Berlioz does not give the exact whereabouts of the hotel in his correspondence, but his letter of 14 April 1868 says it was near the terraces mentioned below.

We are very grateful to Mr. Ian Woolf for further information on the exact location of this hotel and the building which now stands on its site. The Hotel stood at 3, Raoul Bosio in Vieux Nice, which at the time was the rue de la Terrasse. The present building is an annex of the Mairie, and became part of it in 1937 (see next paragraph). The interior garden which was famous at the time has now disappeared.

We are also most grateful to M. Alain Dornic for drawing our attention to the historic origins of the Hôtel des Étrangers, as described in a plaque in the Centre du Patrimoine de la ville de Nice. The building was originally Palace Corvesy, built in 1768 by the architect Philippe Juvarra and commissioned by Clément Guigliotti, later Clément Corvesy de Gorbio. The palace was confiscated in 1792 from Clément Corvesy, comte de Gorbio, and transformed into the celebrated Hôtel des Étrangers. In 1937 it was bought back by the city of Nice which turned it into an annex of the mayoralty which is still extant; a hall was built on the garden, but it has now been replaced by a car park and a school.

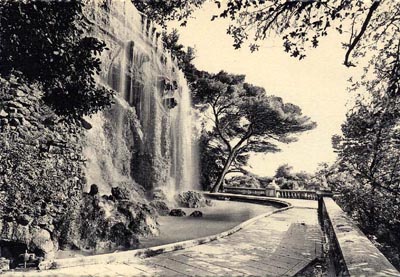

The origins of the terraces date back to the middle of the 18th century when the roofs of a row of low-rise warehouses and lodgings on the seafront were modified to form a terrace on which foreign visitors could go for leisurely walks. They would promenade in both directions and admire the twin attractions of the view of the sea to the south and that of the mountains to the north. In 1839, in order to accommodate the increasing number of tourists, a new parallel terrace was constructed between the old one and the sea. The success of the Promenade des Anglais, which had recently been opened, gradually put these two terraces out of fashion.

It was most probably on the first terrace that in March 1868 Berlioz suffered a stroke and fell, as describedin the two letters cited above (CG nos. 3348, 3354).

At present the terraces are no longer in use as a promenade, but the stairs leading to them are extant and located in the Cours Saleya.

The above oil on canvas painting, reproduced on a postcard, is by the Niçois painter François Bensa (1811-1895). The original painting is in the Masséna Museum.

The above early 20th century postcard is courtesy of Nice d’Antan (HC Editions, 2005).

The Promenade des Anglais was opened around 1822; the English colony in Nice conceived the project and paid the initial expenses.

The above postcard is the reproduction of a lithograph by Delbecchi, based on a painting by Jacques Guiaud (1811-1876); the original lithograph was published in Nice, vues et costumes (1861). The postcard is published by the Masséna Museum in Nice.

This engraving is scanned from Promenade des Anglais, Nice 1833-1933.

The railway station was one of the first major buildings constructed after the reunion of Nice with France in 1860, an event Berlioz celebrated at the time. It was commissioned by the Mayor of Nice, François Malausséna and built by the principal architect of the Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée (PLM) Company, in the neo-Louis XIII style of French railway stations prevalent at the time. The first train arrived at the station on 27 September 1864. The station has undergone many changes and expansions since then but the original building is still extant and forms part of the present structure.

In 1868 Berlioz would have travelled to Nice by train from Paris and back. To travel on to Monaco and back he took the omnibus (CG nos. 3348, 3354).

![]()

See also on this site:

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; the page Berlioz in Nice was created on 7 December 2003; enlarged on 15 April and 1 June 2012, 15 January 2013 and 1 September 2014.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb for all the pictures and information on this page.

![]() Back to Berlioz in Italy main page

Back to Berlioz in Italy main page

![]() Back to Berlioz and France main page

Back to Berlioz and France main page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page