![]()

The 1830s

The 1840s

The visit of 1846

The sequel

Lille in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

Although Berlioz only made one visit to Lille to give a concert there (in June 1846), he nevertheless formed early a positive view of the city’s musical capacities and judged it more than once to be the ‘most musical city in France’ (see below and CG [= Correspondance Générale] no. 1046). To judge from his writings it was in the 1830s that Lille first drew itself to his attention. In April 1837 Berlioz heard reports of performances of his Francs-Juges overture in three cities in France, Lille, Douai and Dijon: the performances had been a success, unlike what happened in London and Marseille (CG no. 493). Shortly after Berlioz published an article on music-making in French provincial cities which appeared in the Revue et Gazette Musicale (11 June 1837; Critique Musicale III pp. 143-9 [hereafter CM]), and which shows that he had been observing the musical scene outside Paris with some care for several years. He was critical of the limitations of the provinces though acknowledged recent progress (pp. 144-5):

Amateur and professional musicians in the provinces are too fond of parading in the limelight. They are not sufficiently prepared to merge their individuality in the whole, and to call things by their name, they are too presumptuous and impatient to devote to rehearsals the care and time that they demand. That is enough to make me question the existence of instrumental music in most of our provinces. Yet the exceptions should be mentioned, and have been growing in numbers these last two years: musical festivals have taken place in Toulouse, Marseille, Douai, Lille and Orléans, and though the details of performance may not be rendered with much finesse, the overall result is nevertheless satisfactory and conveys the import of works which it would have been folly to attempt five years earlier.

Berlioz then goes on to single out for special mention the composer Ferdinand Lavainne (1810-1893), whose musical career was almost entirely associated with the city of Lille, and some of whose scores Berlioz had clearly studied closely, though the performances of these works had taken place in Lille and not in Paris. Berlioz was critical of aspects of Lavainne’s style, but he nevertheless took him seriously as a musician and composer (pp. 145-6):

M. Ferdinand Lavainne had already successfully brought himself to public notice by an oratorio, The Flight from Egypt, which is remarkable for the firmness of its style and ideas that are often elevated and always free from vulgarity. The harmonic writing is careful, but in my view too studied […] yet it is because of the eminent qualities which an examination of his works has revealed that we believe we must urge him strenuously to steer clear of a misguided path into which the ambition to display facility in the art of linking the most unusual modulations may have led him at the outset.

Berlioz then comments on an instrumental work by Lavainne, and a recently performed opera, and concludes (pp. 146-7):

In short, the existence of a score such as this one, composed by a musician from the provinces and performed on a provincial stage, is of unmistakable significance, and it attests to the immense progress made by music in the city in which the author lives. Lille had already brought itself to public notice through a similar initiative. A young composer, M. Lefebvre [1811-1835], whose recent and premature death has been a loss to art, had also written and staged an opera which scored a genuine success. […]

A few months later (Revue et Gazette Musicale, 17 September 1837; CM III pp. 257-9) Berlioz commented on another composer from Lille (J.-J. Printemps) and praised again the city’s musical development:

While some parts of France remain completely foreign to the study of music, in others the progress of this art manifests itself with a brilliance that raises the highest expectations. The most favoured in this respect are without doubt the northern and southern extremities of the land: Marseille and Toulouse on one side, Orléans, Douai and Lille on the other. We do not include Strasbourg, as we regard this city as more than half-German. Among these Lille is probably pre-eminent. At least, a number of considerations seems to assign to it the first rank among cities in France in which music is cultivated: the love for music of its inhabitants, the sacrifices made for her by some of them, day after day, the number of distinguished performing musicians to be found in Lille, and finally the remarkable compositions written by young artists who have developed in that small musical centre without any direct communication with any other.

The sequel suggests that the comments made by Berlioz in these 1837 articles did not go unnoticed in Lille, though it is not possible to point to any direct connection with what happened the following year, when at the Festival of Lille the Lacrymosa from the Requiem was performed twice (25 and 26 June 1838) under the direction of Habeneck (Habeneck had conducted the première of the work on 5th December the year before at the Invalides in Paris). The story is told by Berlioz himself, both in his Memoirs (chapter 47), which first appeared in Le Monde Illustré in 1859 (23 April), and in his correspondence. The account in the Memoirs goes as follows:

[In 1838] the city of Lille organised its first festival, and Habeneck was engaged to direct the musical part of it. He was prone, in spite of it all, to generous impulses, and he may have wanted to try to get me to forget, if possible, his famous pinch of snuff. He had the idea of suggesting to the committee of the festival, among other pieces for the concert, the Lacrymosa of my Requiem. A Credo from a solemn mass by Cherubini was also included in the programme. Habeneck rehearsed my piece with extraordinary care, and it appears that the performance left nothing to be desired. It also made reportedly a great impression, and in spite of its colossal scale the Lacrymosa was vociferously encored by the public. Some members of the audience were moved to tears. As the Lille committee had not done me the honour of inviting me, I had stayed in Paris. But after the concert, Habeneck, overjoyed at achieving such a success with a work of this difficulty, wrote me a short letter in the following terms:

My dear Berlioz,

I cannot resist the pleasure of telling you that your Lacrymosa was performed flawlessly and had a huge impact.

Yours ever,

Habeneck

Lille

The letter was published in Paris in the Gazette musicale. On his return Habeneck went to see Cherubini to assure him that his Credo had been very well done. ‘Yes, replied Cherubini dryly, but you did not write to me!’ [Berlioz here adds a footnote: ‘I had warned him that one day my name would be known to him.’]

The text of Habeneck’s letter as published in the Revue et Gazette Musicale on 1 July reads as follows (CG no. 556):

Dear Mr Berlioz

The first concert has just finished, and I cannot resist the pleasure of informing you that your piece made the greatest effect and was performed to perfection.

Yours sincerely

HABENECK

Berlioz alludes briefly to the event in a letter of 3rd July to Ernest Legouvé (CG no. 558: ‘Have you heard of my success at the Lille Festival?…’), but fuller references come from two letters to his sister Adèle, the first on 28 June (CG no. 557):

[…] My Requiem has just been performed by 500 musicians in Lille, and Habeneck writes to me that the success was immense and the performance flawless; this must be more than true if this old fox has allowed himself to be so carried away with enthusiasm as to write to me about it. I am expecting him and Duprez at the same time to begin my orchestral rehearsals [for Benvenuto Cellini] […].

The second about two weeks later, on 12 July (CG no. 560):

[…] You know of my success in Lille at the Festival (I already wrote to you about it). I was performed by six hundred musicians in front of an audience of five thousand. You have read the newspapers from the Nord Department, as they were reproduced by those in Paris. I have seen many people who attended this musical festival; at the peroration of my Lacrymosa there were tears and even, as stated in several letters, two or three cases of people fainting! I am truly grateful to those ladies for having passed out so well in my honour.

Habeneck, the conductor of the Opéra, was in Lille and was conducting all this; he gave me details that made me regret I had not gone there. He wrote to me after the first concert (my piece was requested again for the second [26 June]), and on his return Cherubini, whose Credo was performed, made some rather sour comments to him about the letter he had sent me. […]

Habeneck’s motives are a matter of conjecture, but it is striking that Berlioz was apparently not consulted in advance by any of the organisers of the Festival, despite his publicly expressed appreciation for the city of Lille, nor was he invited to the performance.

![]()

In late 1840 Berlioz was apparently planning a festival in Lille, according to a letter dated 8 November 1840 of his sister Adèle to his other sister Nancy, reporting news from a friend in Paris: ‘[Hector] was on the point of deciding to go to Lille to give another festival, but as he had received offers on that subject he wanted first to settle carefully the question of money before making a final decision’. The project apparently did not materialise, and Lille seems to drop out of sight for a few years; Berlioz’s thoughts at the time were directed in the first instance to his long-planned journey to Germany, which eventually took place in 1842-43. But in 1844 Berlioz had further tangible proof of the goodwill that existed for him in Lille. In March (?) he and Isaac Strauss started planning for a musical celebration to take place in the summer after the end of the Festival of Industry (CG no. 888), and which eventually took the form of a large concert in 1 August conducted by Berlioz and a popular concert the next day conducted by Strauss. Berlioz’s account of the event in the Memoirs (ch. 53, already published in Le Monde Illustré in February 1858) does not mention in detail how Berlioz recruited his forces and gives the impression that they were all from Paris. But contemporary evidence shows that Berlioz appealed to musicians outside Paris to take part in the festival, and that Lille responded, as Berlioz mentioned in a letter to Strauss (CG no. 912, 25 June):

[…] You know that the city of Lille is sending a deputation of its leading musicians, who are coming at their own expense to take part in the performance. Try to make sure someone comes from Lyon, this would make a very good impression (and similarly for Moulins and Dijon). […]

An article by Berlioz himself in the Journal des Débats on 23 July announced the festival and mentioned the participation of Lille, though not of any other city in France; Lille, it seems, was the exception:

It seems that my voice has even struck a chord in distant places where I did not hope it could be heard: Lille is sending a deputation of its musicians who, under the direction of M. Bénard, the conductor of the theatre, and M. Lavainne, a distinguished composer, will undertake this artistic pilgrimage to Paris to come and take part in the work of the festival. My thanks to all these generous artists!

The following year Berlioz made his first concert excursions to French cities outside Paris, to Marseille in June and Lyon in July, and he had also been considering at the time the possibility of a visit to Bordeaux. On his return from Lyon he was approached by Ferdinand Lavainne in Lille, who in the light of their previous relations could expect a sympathetic response from Berlioz. In his reply Berlioz suggested to Lavainne the possibility of a concert in Lille as a sequel to those in Marseille and Lyon (CG no. 985, 1 August, the only surviving letter of their correspondence):

Accept my sincere thanks for your kind regards and the honour you have done in dedicating to me your fine De Profundis. I would probably have found an opportunity to perform at least part of it last winter at one of my concerts at the Cirque, but the institution which I thought I had founded only lasted as long as the winter. Because of the difficulties in the position of the venue it is really impossible to expose oneself again to the unfavourable circumstances I encountered during the winter season, and during the summer the use of the Cirque by an equestrian group makes it unfeasible to give concerts there.

Besides I believe I will not be in France during the coming musical season, as I am planning to go to Russia.

Would it be possible between now and October to organise a large-scale musical event in Lille, as I have just done in Marseille and Lyon? We could then put on some of my compositions. We would have to reach an understanding with the theatre.

Please write to me about this as soon as possible, as I am about to set off for Bonn where I may spend some three weeks; Liszt is suggesting I give concerts there with him after the Beethoven celebrations.

If we could have in Lille an orchestra of 70 musicians, a chorus of 60 voices and a military wind-band of 26 to 30 players, we could hope for a fairly good result. The theatre would deduct 3,000 fr. for its ordinary expenses and would share the takings with me. This is what I did in Marseille, Lyon and in the whole of Germany. […]

![]()

Nothing came of these plans, and on his return from Bonn late in August 1845 Berlioz started actively planning for his trip to Vienna and central Europe, from which he only returned in May 1846, deeply engrossed in the composition of the Damnation of Faust which he had started during his travels abroad. Not long after his return, in late May or early June, he received an unexpected commission, as emerges casually from a letter to Dr. August Ambros in which he laments not having received any news from Prague which he had recently visited (CG no. 1044, 8 June):

[…] Tell me whether you and all our friends have so completely forgotten me that I cannot get any news from them.

At least say something to me.

I am very busy with Faust, but I have just been forced to interrupt my work to write several feuilletons and a cantata which I am due to conduct in Lille for the celebration of the opening of the Northern Railway [Chemin de fer du Nord]. […]

Prague must be very beautiful now, radiant and in full bloom under this fine summer sun. How I wish I could climb the Hradschin mountain this evening in your company. […]

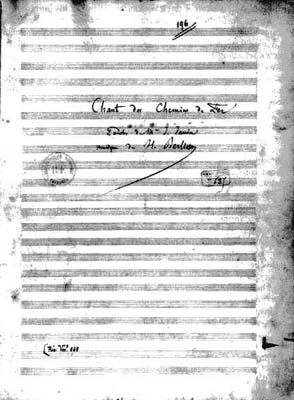

The cantata referred to is the Chant des chemins de fer, commissioned by the city of Lille for the inauguration of the Paris-Lille railway line. The moving spirit behind the commission was the wealthy Lille judge Pierre Dubois (1799-1872), a friend of Jules Janin, the author of the text of the cantata; Janin himself was a close friend and colleague of Berlioz at the Journal des Débats. What is striking is that despite the burden of commitments which Berlioz found after a long stay abroad, he evidently thought the commission important enough to set aside temporarily his work on the Damnation of Faust and devote some two weeks in all to carrying it out: the subject and the social ideas it expressed appealed to him (see the article by Pierre-René Serna on this site). Berlioz travelled to Lille on 10 June, by train of course, though the line was not yet officially inaugurated. Rehearsals took place over the next few days, and the performance of the cantata was on the 14th in Lille’s Town Hall, located at the time in the former Rihour Palace. It was preceded by an open-air performance of the Apotheosis from the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale. Berlioz spent in all a week in Lille. Further details about the concerts are provided by the contemporary press and may be found in the New Berlioz Edition, vol. 12b (pp. VIII-IX). To this should be added the three articles from the Lille press of 17 and 18 June 1846 which are presented on this site by Dominique Catteau. No letters survive from the period of Berlioz’s stay there, and it was only on his return that he was able to inform his correspondents. Two letters both dated 29 June give an account of the event, the first to his sister Nancy (CG no. 1045):

I have been running around a little to keep my legs fit. To begin with I have been for a week a resident of Lille, one of the busiest, and certainly the most serenaded — I have had to face four serenades, three of them instrumental and one vocal. The inhabitants of the great square on which I was staying must have found my presence something of a liability. But all in all the apotheosis [the last movement of the Symphony funèbre et triomphale] went well, and the 250 musicians from the army did a proud job. The cantata was sung with uncommon verve and fresh voices which we are unable to find in Paris for our choruses. But while I was in conversation in the room next door with the Dukes of Nemours and Montpensier who had asked for me, first my hat was stolen, then all the music of the cantata, the orchestral score, some of the parts for chorus and a full score. The upshot is that here is a lost work, as I don’t feel the courage to start all over again. That is all I have gained from this dazzling festival which was sponsored by M. Rothschild, for which I was summoned from Paris and for which I have had to spend three nights composing the cantata.

All the same the Mayor of Lille has sent me in the name of the city a very fine gold medal with the inscription: Inauguration of the Northern Railway, the City of Lille to M. Berlioz. You cannot imagine the crush. At the ball J. Janin lost his Turkish decoration in diamonds which is worth 800 francs. People were dying of thirst, there was not enough accommodation for all the people who had arrived from Paris and Belgium that same day, the members of the town council were arguing and provoking each other, and to crown all this hullabaloo a fire broke out etc., etc. […]

The second letter is addressed to his friend Robert Griepenkerl in Brunswick (CG no. 1044bis [vol. VIII]):

[…] I do not have the slightest musical news of any importance to give you. I have recently been interrupted in the composition of the Damnation of Faust for a cantata which I was obliged to write in four days for the inauguration of the Northern Railways. It was sung with great success in Lille, and the same evening I conducted an open air performance of the Apotheosis of my Funeral Symphony, which was played with great precision by 250 wind players. The misfortune of this excursion to Lille is that in the ballroom where my cantata had just been performed, while I was conversing with the princes who had summoned me, my score and all the vocal and orchestral parts of the cantata were stolen; since then I have been unable to find any trace of them. […]

A few days later, on 2 July, Berlioz wrote to Johann Vesque von Püttlingen in Vienna (CG no. 1046):

[…] I would have written to you three weeks ago to inform you of an approach I made to the director of the Opéra-Comique concerning a libretto you had entrusted to me. But just at that moment I was asked to write a cantata for the festival for the inauguration of the Northern Railway, and I was so pressed for time that I had to spend three nights on it. As soon as the score was finished I had to leave for Lille, where it was to be performed, and it was indeed performed very successfully. I was fêted and serenaded in every conceivable way. The city of Lille is the most musical in France.

Things are now quieter and I have resumed with vigour my work on the Damnation of Faust which is progressing, though it is still far from being finished. […]

This last letter does not mention the loss of the music of the cantata. The score of the cantata was in fact recovered a few years later (by 1849), though the precise circumstances are not clear. A version with piano accompaniment (arranged by Berlioz’s friend Stephen Heller) was published in 1850, though Berlioz never issued the full score in his lifetime (it was first published in 1903 in the Breitkopf edition and it is available in the New Berlioz Edition, Volume 12b). The work, though rarely performed, is available in several modern recordings.

Several years later, in 1848, Berlioz wrote and published an account of his visit to Lille, together with accounts of his visits the previous year to Marseille and Lyon. They were published in the Revue et Gazette Musicale, the section on Lille appearing in the issue of 19 November (CM VI, pp. 449-58). In 1859 Berlioz reproduced all three in his book Les Grotesques de la musique, though the account of the Lille visit omitted a long introductory section, dated 20 October 1848 [CM VI pp. 449-51] and included only the main section, written later and dated 20 November 1848. The account in RGM/Grotesques shows a number of differences with the contemporary letters cited above, and is light-hearted in tone, as though Berlioz was deliberately playing down the importance of his musical excursions to these provincial French cities and of his own cantata. The cantata was, in this account, written ‘in one night’, not four days and three nights as in the letters. Berlioz does not mention the loss of the music, which may indicate that it had been recovered by that date. Although Berlioz gives full credit to the musicians for their performance of the cantata, he tactfully omits any mention of Lille as being ‘the most musical city of France’, which in the context would have been a slight to Marseille and Lyon. But the account adds some details not found in the correspondence, for example that musicians from neighbouring cities (Valenciennes, Douai and others) took part in the concert; and it ends characteristically with a deliberate anti-climax, told at great length — the failure of the artillery twice to fire their cannons during the performance of the Apotheosis of the Funeral Symphony, on which the correspondence is silent.

![]()

For several years after 1846 Lille drops out of sight once more (Berlioz mentions in 1850 the audition at the Conservatoire of a symphony by Ferdinand Lavainne, ‘a composer of great merit who does credit to the city of Lille’: Journal des Débats, 5 February 1850). But in 1851 the possibility arose of Berlioz taking part in a music festival at Lille, as he writes to his sister Adèle on 17 March (CG no. 1392):

[…] Plans are afoot for a Festival in Lille for the end of June, in which all the northern provinces are to take part.

I am supposed to be invited there to conduct two of my works. It will be splendid. Then there is talk of other possibilities for the Universal Exhibition in London, and if only one of them materialises I will be going to England in May.

But what preoccupies me most at the moment is the imminent arrival of Louis. […]

Berlioz was indeed invited in April to act as member of an international jury assessing musical instruments at the Great Exhibition in London and departed the following month. While in London he still expected to attend the Lille festival, as he wrote to his son Louis on 1 June (CG no. 1415):

[…] I am very anxious to hear from you. If your letter arrives in Montmartre, it will be forwarded here. It is better for you to send them all to Montmartre, as I do not know whether I am going to stay another full month in London. I will probably be in Lille on June 1st [sic], to hear the Lacrymosa from my Requiem which is being performed at the Festival of the North; I have just received an invitation from the committee in Lille. […]

In the event Berlioz’s stay in London was prolonged till late July and the projected visit to Lille thus lapsed (the Lacrymosa was actually performed there on 30 June under the direction of Girard, with great success). Thereafter Berlioz had no occasion to return to Lille, though there are a few mentions of the city in several of his feuilletons after this date: Journal des Débats, 2 March 1854 (a Requiem by Henri Cohen, recently appointed director of the Lille Conservatoire), and 4 July 1854 (a sextet by Ferdinand Lavainne, now professor at the Lille Conservatoire; he is mentioned as giving a concert in Paris in a feuilleton of 7 May 1857).

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, all the pictures displayed below have been scanned from engravings, postcards and a 1951 publication in our own collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved. We are most grateful to Pepijn van Doesburg for providing us with his own original 2003 photographs, for which he holds the copyright.

The autograph score of Berlioz’s cantata is in the Bibliothèque

nationale de France, Paris.![]()

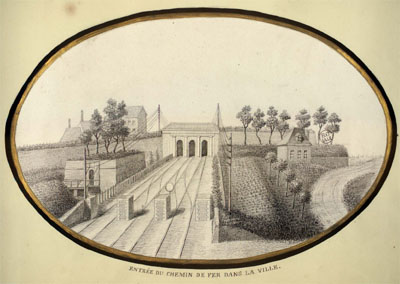

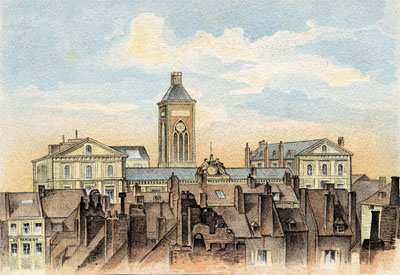

This postcard, posted on 23 May 1915, reproduces an engraving, probably made around the same time.

The above engraving is reproduced here courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lille.![]()

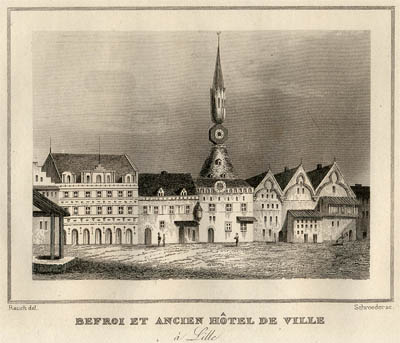

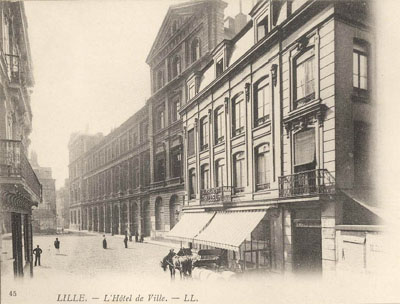

The old Town Hall was called at the time Maison de Ville de Lille and had a beautiful and elaborate clock tower. The building was demolished in 1664 and the town’s archives were subsequently moved to Rihour Palace where a new town hall was housed. After the fire of 1916, the Town Hall was moved in the late 1920s to its present location at place Roger Salengro; it was built by the architect Émile Dubuisson from 1924 to 1928. Its clock tower dates back to 1932.

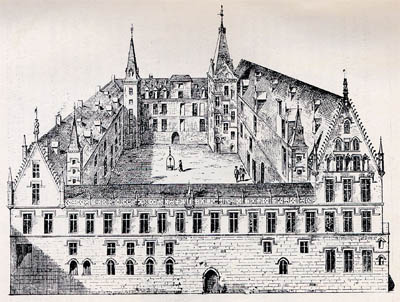

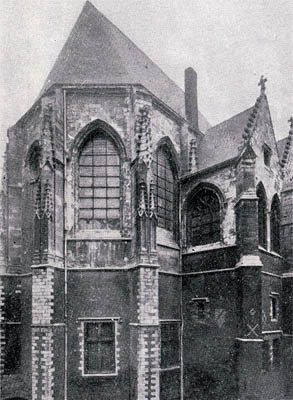

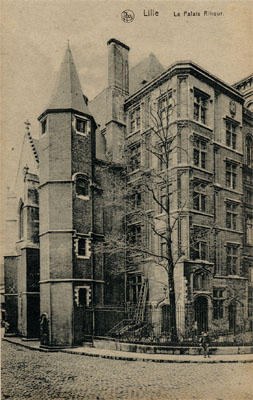

The origins of the Palace date back to 1453 when Philippe le Bon, duke of Burgundy, lay its foundation near the Grand Marché. The Palace was bought by the city magistrate in 1664 and housed the town hall; it was there that in 1846 Berlioz’s cantata was first performed.

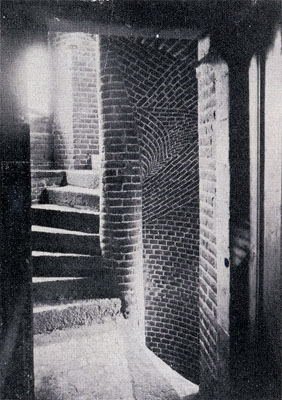

Rihour Palace, like many buildings of similar longevity, has undergone reconstruction over the centuries. For instance, the four wings of the Palace (including the town hall and its clock tower), were rebuilt in neo-classical style, after designs by Charles-César Benvignat, between 1847 and 1859, but the conclave was unaffected by this reconstruction. In addition the Palace suffered three major fires, on 17 November 1700, 6 November 1756 and 23 April 1916, the last of which destroyed much of the complex. The chapel and the turret (with its staircase) in late Gothic style escaped the fire and they are all that remain of the building that Berlioz knew. Place Rihour now occupies the spot where the Palace once stood.

The above 1834 engraving was made by J. Schroeder after a drawing by C. Rauch, based on the available contemporary documents.

The above engraving was published in Guide Illustré Historique et Descriptif de l’Exposition rétrospective de la Toison d’Or, Lille, Palais Rihour, 5-20 May 1951.

The above engraving is reproduced here courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lille.

The above postcard is reproduced here courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lille.

The above photo is reproduced here courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lille.

The above photo was published in Guide Illustré Historique et Descriptif de l’Exposition rétrospective de la Toison d’Or, Lille, Palais Rihour, 5-20 May 1951.

The above photo is reproduced here courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lille.

The above engraving was published in Guide Illustré Historique et Descriptif de l’Exposition rétrospective de la Toison d’Or, Lille, Palais Rihour, 5-20 May 1951.

The above card was posted on 28 June 1940.

The above card was posted on 26 October 1915.

The arch on the right in this photo is a relic from the neo-classical town hall of 1847-1859.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel

Austin on 18 July 1997;

Berlioz in Lille page created on 11 July 2003, enlarged on 17 January

2004 and on 15 February 2011. Revised on 1 July 2023.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.