Berlioz and the Americas

The 19th Century

|

Berlioz and the AmericasThe 19th Century

|

|

Introduction

Musicians on the move

Berlioz on the Americas

Invitations to travel

Berlioz’s music in America

Excerpts from Berlioz’s correspondence

Table of performances of Berlioz in the United States in his lifetime

Programme notes: Harold in Italy (1863) and the Fantastic Symphony (1866)

Illustrations

Portraits of conductors

Concert programmes — in Berlioz’s lifetime

Concert programmes — after his death

This page is also available in French

See also: Berlioz and the Americas — Concert programmes of the 20th century

Allen Lott = R. Allen Lott, ‘A Berlioz Premiere in America: Leopold de Meyer and the Marche d’Isly’, in 19th Century Music, vol. 8, no. 3 (Spring 1985), pp. 226-30

CG = Correspondance

générale (8 volumes, 1972-2003)

Débats = Journal des Débats

Grotesques = Les Grotesques de la musique

Holoman = D. Kern Holoman, Catalogue of the Works of Hector Berlioz (1987)

Saloman = Ora Frishberg Saloman, Listening Well. On Beethoven, Berlioz, and Other Music Criticism in Paris, Boston, and New York, 1764-1890 (Peter Lang, New York, 2009)

Soirées = Les Soirées de l’orchestre

![]()

Berlioz’s musical career is punctuated by a series of wide-ranging travels in Europe, from his trip to Italy in 1831-1832 after winning the Prix de Rome of 1830 to his last trip to Russia in 1867-1868 at the very end of his career. In between came numerous trips to Germany, Belgium, central Europe and London. But like other major contemporary musicians — Liszt, Schumann and Wagner, among others — Berlioz never crossed the Atlantic, though many other European musicians did, and Berlioz might conceivably have followed their example. Very early in his career, in 1826-7 and again in 1835, he did contemplate trying out his fortunes in the Americas. There was interest in him and his music in north America from at least the late 1830s onwards, and from the early 1850s he received from time to time invitations to go and give concerts there. In the event he did not take up any of these, but might well have done so if circumstances had been different. It is legitimate to speculate on the possible impact of a trip by Berlioz to north America, given the long-term effects of his other trips, notably those to Germany and Russia. This page collects the evidence of Berlioz’s relations with the Americas, especially but not exclusively North America and the United States. It is illustrated with evidence from Berlioz’s writings, notably his correspondence and his articles in the Journal des Débats, and with reproductions of concert programmes in our collection of performances of his music, mainly in New York, in his lifetime and later in the 19th C after his death.

The terminology used by Berlioz to refer to the Americas is not always consistent; it reflects that of his own time and is similar to that of the present day. Berlioz sometimes talks of ‘the Americas’ in the plural when he means both North and South America; alternatively, he might say specifically ‘North America’ or ‘South America’ when he wants the distinction to be clear. When he uses ‘America’ or ‘American’ on their own, he occasionally means both Americas, North and South (see below for one example), but more frequently he is referring to the whole of North America (the United States and Canada). On the other hand, by ‘America’ he very often means the United States specifically, as the context usually makes clear. The reason for this usage is of course that unlike other American countries, north and south, such as Canada or Brazil, there was in the case of the United States of America no adjective to refer to the country or its people specifically: hence the use of the generic ‘America’ as a convenient shorthand to refer to the country and people that was most prosperous and conspicuous in the whole continent of America.

Starting in the late 15th century the Americas were settled by colonists from Europe, and new countries were created there, at the expense of the indigenous populations. From this time onwards a steady stream of peoples from Europe travelled across the Atlantic, some settling there permanently, others returning home after their travels. Europe in the 19th century was a world of expanding horizons, and crossing the Atlantic in both directions became increasingly commonplace. Berlioz himself had shown from his childhood a keen interest in foreign countries and distant travels, as he relates in his Mémoires (chapter 2), and says that he even toyed with the idea of a career at sea. That passion was inherited by his son Louis, who became a sailor and eventually commanded his own ship. There are numerous references in Berlioz’s correspondence to his son’s travels, including to central America (see for example CG nos. 2698, 2871, 3241), but tragically Louis was to die in Havana during one of his travels (5 June 1867).

What attracted Europeans to the Americas was simply the lure of wealth. The early years of Berlioz’s career in Paris show him to have assumed, like many of his contemporaries, that the Americas, south as well as north, were lands of opportunity where fortunes could be built. In 1826 Berlioz, short of money and feeling that his father was not prepared to support his musical studies, contemplated travelling to Brazil to restore his fortunes (CG no. 63, cf. no. 696). He relates later thinking of seeking employment around the same time as a flautist ‘in a theatre orchestra in New York, Mexico, Sidney or Calcutta’ (Mémoires, chapter 12). In 1835, now married to Harriet Smithson and with a young son, he thought again of leaving, this time for North America (CG no. 439). On both occasions he held back, but many other contemporary European musicians did not. The Americas provided them with opportunities which Europe often could not, and political instability created further incentives to travel: the revolutions of 1848 resulted in the displacement of many, musicians included, who needed to find a living elsewhere and were drawn to the Americas. Berlioz’s writings, especially his feuilletons in the Journal des Debats, provide numerous examples of such musicians from Europe who ventured across the sea to the Americas, and among them almost every kind of musical talent was represented. The examples mentioned by Berlioz represent of course only a fraction of a no doubt much larger total.

Most conspicuous were some of the famous singers of the day, who were in great demand in the leading opera houses of the Americas (Havana, Rio de Janeiro, New Orleans, New York) and could command exorbitant fees that most European opera houses were unable to match. These included singers such as Rosine Stoltz, who sang Ascanio in Benvenuto Cellini in 1838 and made two visits to Rio de Janeiro (Débats 8 June 1855; Grotesques VI); Henriette Sontag, much admired by Berlioz, and who actually died while on tour in Mexico (Grotesques VI, from Débats 5 October 1854); the celebrated Jenny Lind, whose arrival in New York in 1850 caused a sensation, as Berlioz reported (Soirées 8, from Débats 27 August and 25 September 1850, cf. 19 October 1850) and was illustrated in contemporary cartoons in the European press (see the page in Memorabilia); or Mme Charton-Demeur, who was to sing Béatrice in 1862 and Didon in 1863, and who made repeated visits to the Americas — Rio de Janeiro, Havana — though was unable to accept an engagement in New York in 1861 because of the American civil war (Débats 25 November 1854, 20 July 1858, 3 July and 21 December 1861, 23 December 1862; CG nos. 2575, 2646, 2690, 2694). In other articles Berlioz mentions some less famous names: Mlle Blangy in New York (Débats 7 October 1846), Mme Bosio in Havana (Débats 6 February 1853), Mme Lagrange in Brazil (Débats 20 July 1858). It will be noted that all of these singers were women: for whatever reason, male singers who crossed the Atlantic seem to have been fewer in number, or at least they did not attract as much attention (one example is the tenor Tamberlick: see Débats 3 April 1858).

Among instrumental players, virtuoso pianists were assured of success: Léopold de Meyer, the Austrian pianist who became associated with Berlioz in 1845, was early in the field with a successful tour of North America in 1845 and 1846 (Débats 4 March 1845, 7 October and 29 November 1846; see also below). Henry Herz, a celebrity in Paris for many years, followed close on his heels, this time with a prolonged tour of North and South America which lasted several years; he travelled first to New York, then to Boston, Philadelphia and Halifax, and then (with his piano!) to California, and finally to South America (Débats 7 October 1846, 27 August 1850, 30 September 1851, cf. 19 November 1862). In 1856 Thalberg set sail for North America (Débats 24 September 1856). A different case was that of Berlioz’s close friend Stephen Heller, who as a result of the hardships caused to many musicians (and others) by the revolutions of 1848 considered going to Brazil (Rio de Janeiro) to give piano lessons, but in the event was persuaded to stay in Europe (Débats 15 December 1848).

String players were also in demand. At the same time and for the same reasons as Stephen Heller toyed with the idea of travelling outside Europe, the Austrian violinist Moëser did actually leave for Brazil (Débats 15 December 1848). The celebrated violinist Sivori had previously made a trip to North America in late 1846 (Débats 7 October 1846), as had the cellist Max Bohrer in 1843-44 (Débats 9 January 1844, 29 April 1845). Another cellist, Dominique Tajan-Rogé, a friend of Berlioz since the 1840s, travelled to North America later in the 1850s: he is found in New Orleans in 1855, and in New York in 1857 (Débats 26 April 1857). Though the major European composers of the day seemed reluctant as yet to cross the Atlantic lesser names did. Among these Berlioz mentions Julius Benedict who in 1851 went to North America and Havana (Débats 30 September 1851), and Vincent Wallace who in the course of his wide-ranging travels was active in New York (Débats 31 October 1850, reproduced in Soirées 2nd Epilogue; cf. CG no. 2317).

Among other musicians Berlioz mentions the conductor Barbieri, whom he had met in Bremen in 1853, and who in 1854 was in charge of the orchestra of the opera at Rio de Janeiro (Débats 25 November 1854). Another conductor, Eugène Prévost, had settled in New Orleans in the early 1840s as director of the opera house there, though his career was brought to a halt in 1861 with the outbreak of the American civil war (Débats 12 November 1861). Max Maretzek, the chorus-master at Drury Lane in 1847-1848, later emigrated to North America and worked as impresario in New York and also Havana (Débats 12 November 1861, 23 May 1862). Even instrument makers were tempted by the New World: Berlioz’s correspondence reveals the case of his own cousin Jules Berlioz, who had constructed a new organ; in 1848 he considered travelling to North America to explore the market, and asked his cousin Hector to provide him with information on the costs and opportunities of such a trip (CG nos. 1238, 1241; compare the case of Steinway below).

There was of course also movement in the other direction: American musicians travelled to Europe. The singer Mlle Nau, who sang at the Paris Opéra for many years from the mid 1830s onwards and is frequently mentioned by Berlioz in his feuilletons, was in fact American born, as emerges from a passing allusion in one of these articles (Débats 12 April 1840). Elsewhere Berlioz gives warm praise to the American-born pianist Gottschalk who gave concerts in Paris in 1850 and 1851 (Débats 13 April 1850, 13 April 1851). At the great Exhibition in London in 1851 one member of the jury on which Berlioz sat was an American, one J. Robert Black, and Berlioz mentions the presence of Americans among the cosmopolitan crowds that flocked to the festival at Baden-Baden in 1861 (Débats 3 July 1861). He even introduced a fictitious American musician among the orchestral players in his Soirées de l’orchestre, the bassonist Winter; Berlioz slyly points out that Winter spoke with an American, not an English accent! (Soirées 10, beginning).

The frequent references in Berlioz’s writings to musicians crossing the Atlantic show how he assumed the Americas were an integral part of the musical world of his time, and how he kept himself informed about what was happening there (through newspapers, travellers’ stories etc.). They also reveal something of his attitudes to the Americas, which were very mixed. He viewed them from the point of view of a European, for whom Europe was naturally assumed to be the centre of the civilised world. He never set out his views on the Americas at length in any single passage, but they are implicit in the numerous incidental remarks that are scattered in his different writings.

The Americas belonged in the first place to the same category as the other distant lands around the world which in Berlioz’s time were in the process of being colonised by Europeans. Their inhabitants did not have the same level of civilisation as Europe did, and in some cases their populations could simply be thought of as ‘savages’ who were backward until the arrival of the European settlers (cf. CG no. 2979). But these very European settlers could not be assumed to bring to these new countries all the best that Europe had to offer. Concerning North America specifically (i.e. the United States) Berlioz acknowledged its dynamism and material efficiency: in one letter he describes himself as a ‘heavy German locomotive’ while his correspondent is ‘an American one which travels at 100 km an hour belching out torrents of sparks without emitting any smoke’ (CG no. 2349). But he viewed the country as a whole as utilitarian and dedicated to the pursuit of material gain, to the almost complete exclusion of everything else. ‘I do not know whether your love for this great people and its utilitarian culture is any stronger than mine... I rather doubt it’, he writes to his friend Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 2566). He quotes elsewhere the American saying ‘Time is money’ which he wishes could be turned into ‘Time is art’ (Débats 24 September 1856). In the context of a discussion of current attitudes to art he has a striking comment on the settlement of the Far West which was currently underway (Débats 24 September 1857):

Today’s civilised peoples, so different from those of antiquity, treat certain arts more or less in the same way as the American pioneers are treating the prairies of the Far-West. Attracted by the beauty of a site, by the luxuriant vegetation which grows there, by the purety of the waters and the mildness of the temperature, these vagabonds pause there for a few days, and cut, burn, tear up everything that is green and in blossom, pasture their cattle, hunt and pillage. Then, when the finest trees have been felled, when the grass has been stripped bare, when the most splendid flowers have been crushed under the feet of the animals and covered with their dung, the pioneer breaks camp and seeks out elsewhere some new masterpiece of nature to pollute.

Concerning the many musicians who travelled to the Americas, Berlioz needed to be persuaded that they did so for better reasons that the simple pursuit of wealth. When in 1849 he heard that Liszt was contemplating a tour of North America (which he never undertook), Berlioz’s reaction was lukewarm (CG no. 1250): ‘To cross the Atlantic in order to play music for the Yankees, whose sole concern at the moment are the mines of California!... You alone can pronounce on the usefulness of such a trip’. He described the idea as ‘violent’. This brings to mind his characterisation of the Irish composer Vincent Wallace: ‘An excellent excentric man, phlegmatic in appearance like some Englishmen, but at heart rash and violent like an American’ (Soirées 2nd Epilogue). In 1855 Berlioz reported that Rosine Stoltz was making a return visit to Rio de Janeiro: ‘And Mme Stoltz is going back to Brazil! 450,000 francs! […] How can you resist?… But let us at least resist, and refuse to let our heavens be pillaged in this way, and our stars abducted by these people from the Antipodes, who all have their heads turned upside-down’ (Débats 8 June 1855). The previous year he had deplored the death of Henriette Sontag while on tour in Mexico: ‘Poor Sontag! To go and die so miserably, so absurdly, far from Europe, which alone could know what a great artist she was!’ (Grotesques VI). In yet another passage he mocks the extravagant, un-European, reception given in 1850 in New York to Jenny Lind (Soirées 8): ‘Whatever we do in Europe we will always be outclassed by the enthusiasts of the New World, who are to ours as the Mississipi is to the river Seine’.

On the other hand Berlioz was not indifferent to the fate of his music in America nor to his general reputation there. In 1852 he noted with satisfaction that the success of his concerts at Exeter Hall in London had reverberated in America (CG no. 1500). In 1857 he was keen to discuss with his Swiss publisher the possibility of increasing sales of his music in America (CG no. 2233; cf. 2679). Berlioz was capable of taking a more positive view of music-making in the Americas; a passage in a feuilleton of 1854 is worth citing here (Débats 25 November 1854):

Now that we have more or less recovered from our prejudices over the state of music in England, I believe we are also going to have to rectify our opinions on America’s musical institutions. Leaving aside New York, where you can hear nowadays large-scale and very careful performances of the serious works of ancient and modern music, thanks to the considerable and ever-increasing influx of musicians from Europe, the theatre of New Orleans and that of Rio de Janeiro must be taken into account. The latter, a provisional theatre like that of the Paris Opéra, is on a very large scale, and though not furnished in a luxurious manner, is at least built to provide the best conditions for the acoustic and for the convenience of spectators. You find there an orchestra of 70 very passable musicians, directed by a capable conductor I met in Bremen last year, M. Barbieri. Mme Charton-Demeur […] is having fabulous success at the moment at Rio’s Grand Opera and earning tropical ovations.

The evidence for the invitations Berlioz received from America comes entirely from his correspondence, and not from his other writings. Given that his known correspondence represents only a fraction of what once existed, it may well be that in the course of his career he received more invitations than we know of.

The first known approach came as early as 1836, and from an unexpected quarter: he received a letter from New Orleans — not New York, from where all subsequent invitations were to come — requesting that he send manuscript copies of some of his orchestral music for performance. This presumably refers to the Symphonie fantastique and Harold en Italie, for which Vienna and Milan had made a similar request not long before (CG no. 486). Berlioz, who had yet to embark on his long-planned tour of Germany (it did not materialise until late in 1842), refused all these requests, and with good reason. The music was as yet unpublished, and he was determined not to let it be performed by anyone but himself, and thus risk being misinterpreted and disfigured.

The next known offer came years later, in 1852, by which time Berlioz had made many trips abroad, to Germany, Central Europe, Russia, and London, and built up a considerable international reputation as both composer and conductor. It is not known from whom the offer emanated, but it was sufficiently serious to tempt him, at least with the prospect of earning enough to be able to give up his burdensome work as music critic; he refused it while still keeping open his options for the future (CG nos. 1499, 1500).

The next offer, some five years later in 1857, was even more tempting. It involved this time a five-month tour of North American cities (New York, Philadelphia, Boston) for which a large fee of 20,000 dollars was offered, plus travel expenses. Because of his work on the composition of Les Troyens, and also because of his health, Berlioz declined, while declaring his readiness to go the following year (CG nos. 2222, 2233, 2235). The surviving allusions in Berlioz’s letters evidently do not tell the full story; they imply continued negotiations over the following months, and considerable eagerness on the American side to entice the composer to the American continent. In the event the plans all fell through. The offer may conceivably have emanated from the impresario Bernard Ullman, who in 1858 organised a festival in New York in April, one part of which was devoted to the music of Berlioz (see below and the table of concerts). In the course of the festival Ullman announced that Berlioz would be coming the following year — which did not happen (on Ullman’s activities later see Débats 3 July 1861; CG no. 3197).

Another offer came in 1861, but this time Berlioz’s reaction was noticeably cooler (CG no. 2566). Berlioz does not give any details, but dwells rather on his reasons for not accepting: invincible ‘antipathies’ on his part, his disdain for money, and lack of sympathy for the ‘utilitarian culture’ of America… Besides, the fate of Les Troyens was still in suspense. According to CG (volume VI p. 239 n. 6) the invitation may have come from the impresario Max Maretzek, whom Berlioz had met in London in 1847 and was now established in New York (see above). Be that as it may, several more years were to elapse before any further invitation from America (whether the delay was in any way related to the effects of the American civil war of 1861-1865 is uncertain).

The last known offer to Berlioz, and the most serious, came as late as 1867, by which time Berlioz’s health had deteriorated even further, and his inclination to travel diminished correspondingly. It came from a new source, the piano-manufacturing firm of Steinway in New York. The founder of the firm, the German Heinrich Steinweg (1797-1871), had emigrated from Brunswick in 1850 to set up his manufacture in New York, where he anglicised his name to Henry Steinway; his firm prospered and established a strong reputation. Theodore Steinway (1825-1889), one of his sons, remained at first in Brunswick: in 1856 he wrote a letter of congratulations on behalf of the musicians of Brunswick to Berlioz on the occasion of his election to the Institut, for which Berlioz thanked him warmly (CG no. 2166, 28 August 1856). In 1865 he eventually joined his father in New York on the death his two brothers and took charge of the firm. Steinway Hall, a large concert hall at 14th Street, New York, opened in 1866. Early in 1867 Berlioz received a request for a bust of himself to adorn that hall (CG no. 3211): Steinway had probably already then conceived the plan of attracting the composer to New York. Later in the year he visited Paris for the Universal Exhibition where he exhibited some of his pianos; they received the endorsement of none other than Berlioz himself, a demanding critic with a long experience of musical instruments (CG no. 3278). (It should be said that Berlioz was not on the panel of judges of musical instruments, unlike in 1851 in London and 1855 in Paris.) Berlioz’s letter (dated 25 September) makes no mention of any invitations to New York. And yet earlier in the year, in June, he had received repeated offers to go to give concerts in New York where, he was told, his music was very popular (see the following section); he described the offers as ‘very seductive’ but nevertheless refused on the grounds that he was not in a position to undertake such a journey (CG nos. 3244, 3245). This was, it should be said, before he heard late in June the news of the death of his son Louis in Havana. The proposal is ascribed by Berlioz to ‘several Americans’ who are not named, but they must have included Steinway himself or his agents. Then in September Berlioz received an invitation from the Grand-Duchess of Russia to give a series of concerts in St Petersburg during the winter, an offer which he accepted after consultation with his friends (18 September; see the page on Russia). His acceptance of the Russian offer contrasts with his earlier refusal of the repeated American advances. Steinway heard of Berlioz’s plans for Russia, and encouraged no doubt by Berlioz’s letter of 25 September praising his pianos, promptly came back on 27 September, and again in early October, with a generous offer and the hope of luring Berlioz to New York the following year. But Berlioz refused again (CG nos. 3279, 3283, 3284, 3286). By the time he came back from Russia the following year his musical career was effectively over, and he was no longer able to undertake any long-distance journey. There was no further talk of the invitation to New York, only of the completion of the bust for Steinway and of copies of it (CG no. 3346). Berlioz thus never visited America — though at least his bust went there in his lifetime.

News of musical developments in Europe travelled regularly across the Atlantic, by word of mouth and through the press, just as they did within Europe itself. As seen in the previous section, interest in Berlioz and his music in north America developed well in advance of any performance of his works there: in 1836 New Orleans requested from the composer manuscript scores of some of his music for performance, at the same time as Berlioz was receiving similar requests from some European cities (CG no. 486). But as the case of New Orleans shows, interest in Berlioz’s music was not sufficient: the precondition for independent local performance of his works was the availability of published scores and orchestral parts. And here Berlioz was deliberately slow in publishing his compositions: when he set out for his first major tour of Germany in late 1842, much of the music he performed was as yet unpublished and he had to travel with a considerable load of manuscript material. His reasons for doing so are well known and were based on his own experiences: in 1834 the conductor Girard mishandled the first performance of Harold en Italie (Mémoires chapter 45), and in 1836 the publication of the overture to Les Francs-Juges resulted in the appearance of a distorted arrangement of the work in Germany. As a result Berlioz decided first, that he had to conduct himself the early performances of his works so as to establish a correct performing tradition, and second, that he should delay the publication of his music so that it should not be misrepresented in his absence. It also allowed him to test his music in performance and to make improvements to it in advance of publication. Hence until well into the 1850s there was a significant time-lag between the first performance of many of his works and their actual publication. The Requiem, first performed in 1837 was an exception and was published the following year. The earliest works to appear otherwise were several of his overtures: Waverley and Benvenuto Cellini, both in 1839 (first performed in 1826 and 1838 respectively), Le Roi Lear in 1840 (first performed in 1833), Le Carnaval romain in 1844 (first performed in the same year). But the symphonies had to wait longer: the Symphonie fantastique till 1845 (first performed in 1830, and substantially modified since then), Harold en Italie till 1848 (first performed in 1834), Roméo et Juliette till 1847 (first performed in 1839); the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale appeared earlier than the others, in 1843 (first performed in 1840). The consequence of this was to delay the chance of independent performances of his works abroad, and this included north America.

The known performances of Berlioz’s music in his lifetime in north America (i.e. the United States) are summarised in the table below. It should be repeated here that the information provided is likely to be incomplete and will probably need to be supplemented or corrected in due course.

As can be seen, the first that New Yorkers heard of Berlioz (in 1845) was not one of his own works, but an orchestral arrangement by him of a piano piece. This happened in the course of a concert tour of North America by the Austrian pianist Leopold de Meyer in 1845 and 1846 (see also above); Meyer had appeared with great success at a concert of Berlioz in Paris in February 1845, which prompted Berlioz to orchestrate Meyer’s Marche marocaine which he performed, again with great success, at another concert in April. In New York Meyer conducted himself the orchestral version, which was announced by the New York Herald as “instrumented by the great Berlioz, with an original Coda, and executed in Paris under his direction with astonishing effect” (Allen Lott p. 228 n. 12). The following year (1846) the work was repeated in New York in October and November, with George Loder as conductor, together with another march by Meyer, the Marche d’Isly which Berlioz had also orchestrated; the New York Herald again announced the new piece as “expressly arranged for the orchestra by the celebrated Berlioz in Paris” (Allen Lott p. 230 n. 13). The Marche d’Isly received a further performance in Philadelphia on 10 November, this time conducted by Meyer himself; the announcement for this concert is reproduced by Allen Lott (p. 230); it also described the work as “Instrumented by the celebrated Berlioz of Paris”.

By the end of the year 1846 New York had heard the very first performances in the Americas of Berlioz’s own music, the Francs-Juges overture on 7 March and the overture Le Roi Lear on 21 November. The Francs-Juges was conducted by A. Boucher (on whom we do not have further information) and Le Roi Lear by George Loder (1816-1868). Loder came from an English musical family and had settled in America as early as 1836, where he played an important part in the early years of the New York Philharmonic Society (founded in 1842). He gave there the first American performance of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, and also conducted the three performances of the marches by Meyer mentioned in the previous paragraph (he later went to Australia, where he died).

After 1846 there was an apparent lull in performances of Berlioz in North America until the 1850s when the pace gradually increased. Until this time Berlioz did not have any obvious champion on the American musical scene, but from at least the mid-1850s this was to change. Three conductors were to emerge who showed in one way or another a particular interest in Berlioz’s music: Theodore Eisfeld, Carl Bergmann, and Theodore Thomas. All three were German musicians who came to settle in North America. This is no coincidence: it reflects not only the important role played in music in Europe by Germans at this period, but is also an indirect illustration of the impact that Berlioz had started to have in Germany already in the 1830s, which was then considerably amplified by his travels in the 1840s and 1850s.

Theodore Eisfeld (1816-1882) emigrated to America in 1848 as a result of the revolution of that year. From 1849 to 1866 he frequently conducted the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, and from 1862 to 1865 also that of the Brooklyn Philharmonic Society. He is known to have conducted the overture Le Roi Lear twice, in 1853 and again in 1864 (see also CG nos. 2970, 2973). Berlioz mentions him as one of his friends in New York (together with Maretzek) in Débats 12 November 1861, but it does not seem to be known when and in what circumstances they first met and became acquainted. Eisfeld’s career was terminated prematurely by ill-health in 1866, and he returned to Germany where he died.

Carl Bergmann (1821-1876), like Eisfeld, also emigrated to America in 1849 after being involved in the 1848 revolution, and like him was active with both the Brooklyn Philharmonic Society and the New York Philharmonic, of which he was sole conductor after Eisfeld’s retirement. He is not known to have had any relations with Berlioz while still in Europe, but his Berlioz repertoire in this period was much more extensive than that of Eisfeld and broke new ground in America. It included the overtures Les Francs-Juges (1856, 1861), Waverley (1856), Le Carnaval romain (1856, 1861, 1862, 1865, 1866), and Le Corsaire (1863), four movements from the Symhonie fantastique (1866, 1868), two from Roméo et Juliette (1867), and Weber’s Freischütz with Berlioz’s recitatives (1860).

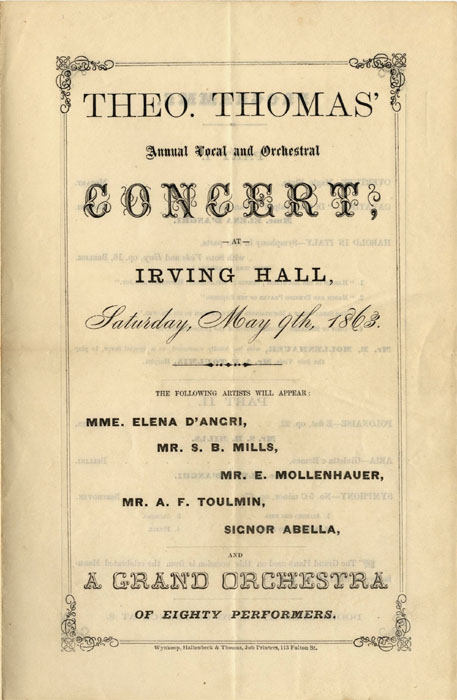

Theodore Thomas (1835-1905), younger that his two colleagues, emigrated earlier than them in 1845. Because of his young age at the time he did not have any connection with Berlioz dating from his period in Germany, but once in America went on to develop an interest in his music, and over his career as a whole he promoted Berlioz more than Bergmann had done. He started off as a violinist before turning to conducting, and gave performances of the Rêverie et caprice, though not with orchestral accompaniment (1859). His remaining Berlioz repertoire up to 1869 included the overture Benvenuto Cellini (1867, 1868), four parts of Roméo et Juliette (1864, 1867, 1868; cf. 1881), and especially a complete Harold en Italie (1863, 1866). The work became a great success in New York, a development which pleased Berlioz greatly (CG nos. 2840, 2856, 3076, 3244). In 1867 Thomas made a trip to Europe and paid a visit to Berlioz at his home address in Paris (8 May), on which occasion Berlioz presented him with a copy of the new Ricordi edition of the Requiem, as related by Thomas himself in his diary (cited by David Cairns, Berlioz volume II [1999], p. 749). (See also below.)

Taken as a whole, the performances of Berlioz in America during the composer’s lifetime by these three conductors succeeded in popularising his music, especially in New York. Berlioz received reports of this, through friends and through the press, and noted this with satisfaction (CG nos. 2856, 2970, 2973, 2982, 3032, 3076, 3244). The popularity of his music is implicit in the repeated performances of some works, notably the overtures (especially Les Francs-Juges, Le Roi Lear and Le Carnaval romain), excerpts from Roméo et Juliette and the Symphonie fantastique, and the complete Harold en Italie. It will be noted that on almost all the concert programmes reproduced below the works by Berlioz are, with the exception of the concerts of 9 May 1863 and 20 April 1867, placed at the end of the concert; in the case of the concerts of 9 May 1863 and 20 April 1867 they come at the end of the first part. The intention was presumably to give those works greater prominence. Mention should also be made of the great success of the ‘Berlioz Night’ organised in New York in 1858 by the impresario Bernard Ullman as part of a grand Festival: one part was devoted to popular works of Berlioz (the Francs-Juges overture, Weber’s Invitation to the Dance in Berlioz’s orchestration, and the Marche hongroise). Such was the success of the festival that it had to be given four times in quick succession (19, 20, 21, 23 April 1858). On the other hand the limitations of the repertoire covered are evident: neither the Fantastique nor Roméo were performed complete till after the composer’s death, and apart from performances of Weber’s Freischütz with Berlioz’s recitatives, none of Berlioz’s choral and vocal works were attempted, not even Part II of L’Enfance du Christ (La Fuite en Égypte), though its instrumental and vocal requirements were extremely modest. All that was played of La Damnation de Faust were orchestral excerpts.

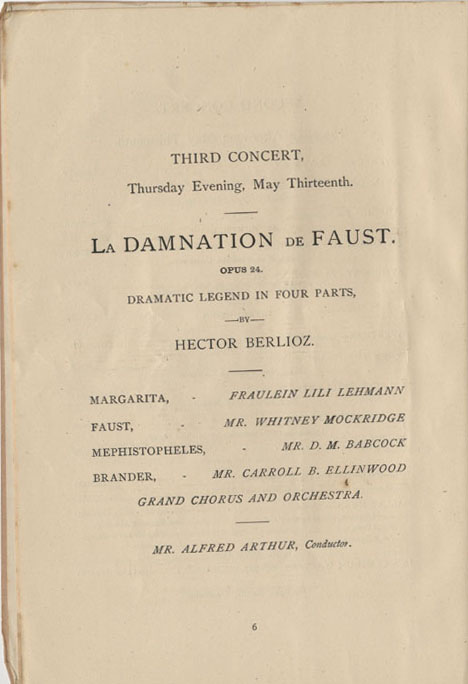

For this America had to wait for the arrival of another German conductor, Leopold Damrosch (1832-1885; portrait below), who only emigrated to America in 1871, much later than the others mentioned. Like Berlioz himself, Damrosch had abandoned a career in medicine that his parents urged on him to devote himself to music as a violinist, conductor and composer. He was active in Breslau (Wroczlaw) from 1858 onwards and developed independently a special interest in contemporary music, namely Berlioz, Liszt and Wagner. Berlioz met him in Löwenberg in April 1863 and was informed that Damrosch had performed the Queen Mab scherzo in Breslau with great success (CG no. 2714). His move to the United States was to transform the scene as regards performances of Berlioz’s music, and the list of works he premièred there is extensive (for what follows see the table in Saloman pp. 210-15). This includes the first complete performances of the Symphonie fantastique (1879), La Damnation de Faust (1880; cf. also 1886), the Requiem (1881), Roméo et Juliette and L’Enfance du Christ (both 1882). In addition he performed excerpts from Les Troyens à Carthage (1877). His son Walter Damrosch (1862-1950) — he was born in Breslau while his family was still in Germany — followed in his father’s steps in his promotion of Berlioz’s music. The activities of Damrosch stimulated Theodore Thomas to extend his own Berlioz repertoire to include some novelties, notably a few shorter vocal works (1887 and 1888), excerpts from the operas (Benvenuto Cellini [1882], Les Troyens [1882 and 1883] and Béatrice et Bénédict [1881]), and the first American performance of the complete Tristia (1885).

It will be noted that the upsurge of interest in Berlioz in America in the late 1870s and through the 1880s coincides with the Berlioz revival in Paris after the composer’s death and the activities of leading conductors there, notably Jules Pasdeloup and especially Édouard Colonne. It is tempting to conjecture that across the Atlantic the latter development may have influenced the former.

![]()

To Édouard Rocher, (CG no. 63; ca. 10 September 1826)

[…] My father is giving me a sum of 50 francs a month, or at least he told me that next year that is all he would be giving me, and to get me accustomed to this diet, he sent me on the 14th of August the sum of 100 francs telling me that it is all he was able to give me this year. When I received that letter I saw clearly what his objective was, which is to cut me down little by little until he gives me nothing. I therefore immediately approached the Brazilian consul to find out whether there was anything positive I could hope for in South America. His answer was that a French artist could earn prodigious amounts of money in the Republic of Buenos Aires, and that if I wanted to travel there he would pay for my trip and also that of the young man who was talking to him and was due to depart with me. He did not want to enter into any commitment or give anything in advance. That was partly what held me back. Besides, I did not have a penny to travel to Le Havre, and I do not know Portuguese, which takes at least four months to learn. Charles [Bert] and [Antoine] Charbonnel pointed out to me all these reasons; but the most decisive ones for me were the dreadful impression that such a departure would make on the minds of my parents, and the huge hold-up that this trip would have caused to my career. To begin with I would have to give up the Prix de Rome competition in which I am at present the leading contender since Pâris and Simon have now withdrawn. […] In addition, by going to Buenos Aires, the opera I have completed and those that are to be written would run a terrible risk of never being performed in Europe. So therefore I am staying. […]

[Note: According to CG vol. I p. 153 n. 1 Berlioz is confusing in this letter Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro]

To his sister Adèle Berlioz (CG no. 439; 2 August 1835)

[…] (Berlioz is obliged to write articles for newspapers to make a living and has no time for musical composition) Harriet is very upset to see me in such a state of servitude, all the more so as she is unable to do anything herself; at one stage we were on the point of departing for North America, but we were held back by the uncertainty of what fate she might expect, as well as the fact that Louis is too young. […] In a few years’ time there will be virtually no theatres left in France (except for boulevard theatres); there are none left in England, and all actors with any merit in elevated dramatic poetry are fleeing to America. […]

To Robert Schumann (CG no. 486; 19 February 1837)

[…] Last year I received at nearly the same time letters from Vienna and from Milan, requesting a manuscript copy of these two works [the Symphonie fantastique and Harold en Italie]; the intention was not to publish them, but only to have them performed. A few months ago, a similar letter was sent to me from New Orleans. I was not seduced by the very generous offers that accompanied these requests. I have always refused them, and always for the same reason, namely the fear of being betrayed by an unfaithful or incomplete performance. […]

To his sister Nancy Pal (CG no. 696; 13 December 1839)

[…] (In this letter Berlioz refers to the article by Jules Janin on the hardships endured by the composer in 1826-27 during his early years in Paris) As for what did take place there is no point in disputing the facts, as too many artists knew me at the time and saw me at the Théâtre des Nouveautés, so the story could not be suppressed. What is more, I was so desperate at the time and so incensed by the opposition I was facing, that rather than going back to La Côte, as my parents were trying to force me, I requested to be allowed to leave for Bourbon Island [now Reunion Island] or for America. […]

To his paternal uncle Victor Berlioz (CG no. 1238; 26 November 1848) (See also the following letter)

[…] What is Jules doing? [Jules Berlioz, Berlioz’s cousin] Has he completed his organ? Someone who can create such an instrument has evidently the makings of a master and could earn a fortune given favourable circumstances. […] But this is evidently a competitive career, as with all other branches of high-skill industries, and it is only by going to exploit it in North America that it would be possible to tap the seam of gold that it contains. Protestants have a fixation for organs and religious chants, and every day a new church is being built in the United States. This is worth thinking about... […]

To his cousin Jules Berlioz (CG no. 1241; 19 December [1848]) (See the previous letter)

I have only been able to obtain a very small part of the information you requested. I cannot tell you how much capital you would require; but if it is only a matter of a stay in America to explore the ground, I think you would need about five or six thousand francs. I know nothing about the workers you would need to take with you, but you would probably find them over there.

Among other people I approached Michel Chevalier, my colleague at the Journal des Débats, who has lived for many years in the United States. This is what he told me:

The port of departure is always Le Havre. The crossing by sail would cost a maximum of 800 fr. and 1100 francs on a steamer.

The expenses in the United States for food, lodging, etc. could not amount to less that 10 dollars a week, i.e. 55 francs.

Every part of the United States, and Canada, which is Catholic to a large extent, would be suitable for you. […]

But let me advise you: you must start by learning English. It is true that French is spoken, but only to a limited extent, and you would be hindered at every step by this obstacle.

That, dear friend, is all I can tell you on this subject. To make a good start, what is important is to have time and money.

But in the meantime you should learn English. […]

To Franz Liszt (CG no. 1250; ca. 25 March 1849)

[…] Belloni [Liszt’s secretary] tells me about your project of a tour of North America. This seems to me a violent project. To cross the Atlantic in order to play music for the Yankees, whose sole concern at the moment are the mines of California!... You alone can pronounce on the usefulness of such a trip. As to what might be done here in Paris before this, I know absolutely nothing... It varies from day to day depending on whether the thermometer of insurrection is rising or falling, whether socialism indicates stormy weather, dead calm, or settled ugly weather. […]

To Franz Liszt (CG no. 1499; 2 July 1852)

[…] Yesterday I received a proposal from America. It involved going to give a series of concerts in New York. I did not accept; but should I ever do, lured by more favourable offers, it would solely be in the hope of being able on return to resign from my duties as a music critic, which are for me a source of shame and despair. […]

To his brother-in-law Camille Pal (CG no. 1500; 2 July 1852)

I am now back after the most brilliant musical season that London can remember. […] I have been warmly adopted by England; I even received yesterday a proposal from New York, which goes to show that this latest success has reverberated in America. I had to keep a very firm grip on myself not to accept it, as I am hoping for a better one next year. […]

To his sister Adèle Suat (CG no. 2222; 9 April 1857)

[…] I recently received a very serious proposal from some Americans. It involved going next October to spend five months in New York, Philadelphia and Boston, to give performances of my works. I was offered 20,000 dollars (105,000 francs) and my travel expenses. The sum was to be deposited in Paris. After serious consideration I refused for this year, while offering to accept for 1858. I want above all to complete my score [Les Troyens]. The organisers will be arriving in Paris in six weeks, and we will resume negotiations.

My serious friends approve my decision to stay in Paris. Besides, I am so weakened by my nervous complaint that I would not have the strength to carry through such a demanding expedition. […]

To the publisher Jakob Melchior Rieter-Biedermann (CG no. 2233; 14 June 1857)

[…] This year I will be going again to conduct the concert in Baden-Baden, which will take place on 18 August. I will be leaving Paris for Plombières on 15 July, and consequently will not be able to have the pleasure to see you in Paris. But will you not be coming to Baden-Baden? I have a great deal to tell you about our publications. An opportunity might arise next year which could greatly facilitate their sales in America. We will talk about this. […]

To his sister Adèle Suat (CG no. 2235; 26 June 1857)

[…] The American press continues to announce my arrival for the autumn of 1858, as though the whole business was concluded and signed. What strange people these businessmen are! […]

To princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein (CG no. 2264; 30 November 1857)

[…] Everywhere in America the talk is of nothing but bankruptcies, and theatres and concerts are heading for the Niagara Falls. Ours do not run such a risk. We do not have a cataract here, because there is no motion flowing in that direction. […]

To Franz Liszt (CG no. 2317; 28 September 1858)

[…] Wallace the New-Zealander, whose story is to be found at the end of my Soirées de l’orchestre, is once again back from the Antipodes. He is going to visit Weimar in a few months, and would like me to give him a letter of introduction for you. You may welcome him without fear, he will not eat you; exceptionally, and despite beinng a New-Zealander, he has no taste for human flesh. […] I do not know a single one of Wallace’s scores, and consequently cannot tell you anything about them. His opera Maritana was successful in several theatres in England and Germany, and his name is popular in the United States. […]

[Note: Vincent Wallace was Irish-born and not a New-Zealander]

To Alfred-Auguste Cuvillier-Fleury (CG no. 2349 [see vol.VIII p. 470]; 6 February 1859)

[…] I have read it again with almost childish delight, that is if there can be anything childish in the pleasure experienced in being praised by you.

You are talking about my verve, but it is yours which is marvellous! I am at best a heavy German locomotive, while you are an American one which travels at 100 km an hour belching out torrents of sparks without emitting any smoke. […]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 2566; 14 July 1861)

[…] An American impresario wanted to sign me up for the Disunited States this year; but his advances came to nothing in the face of antipathies which I am unable to overcome, and of my very limited passion for money. I do not know whether your love for this great people and its utilitarian culture is any stronger than mine... I rather doubt it.

In any case it would be extremely rash of me to absent myself from Paris for a whole year. I might be asked for Les Troyens at any moment. […][Note: The ‘American impresario’ might be Max Maretzek, whom Berlioz had met in London in 1847-1848 where he was chorus master at Drury Lane Theatre. He subsequently went to settle in the United States where he founded the company of the Italian Opera in New York (see further above). — The ‘Disunited States’ alludes to the American Civil War which broke out at the beginning of the year and lasted till 1865]

To his niece Nancy Suat (CG no. 2575; 1 October 1861)

[…] I have recently recruited an admirable and charming singer for my role of Béatrice (in the little opera Béatrice et Bénédict). She is Mme Charton-Demeur. She was about to leave for America, but the events of the war between the Disunited States have enabled her to break her contract, and I seized her in mid-flight for our opera in Baden-Baden. […]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 2646; 21 August 1862)

[…] They would like to stage Béatrice et Bénédict at the Opéra-Comique, but no Béatrice is available. Our opera houses do not have a woman capable of singing and acting this role, and Mme Charton is leaving for America. […]

To his niece Nancy Suat (CG no. 2679; 11 December 1862)

[…] You are telling me about my book A travers Chants; it is enjoying great success in France, Germany, England and America. . […

To his uncle Félix Marmion (CG no. 2690; 15 January 1863)

[…] I have still not been able to decide to give this opera [Béatrice et Bénédict] at the Théâtre Lyrique where they are asking for it; I cannot find there singers who are up to it and Mme Charton Demeur is in America. […]

To his brother-in-law Camille Pal (CG no. 2694; 3 February 1863)

[…] I am promised everything I want at the Théâtre lyrique [for staging Les Troyens]; they would recruit Mme Charton (who is returning from America) for the role of Dido […]. In August I will be going back to Baden-Baden to give another performance of Béatrice with Mme Charton-Demeur. […]

To James William Davidson (CG no. 2695; 5 February 1863)

[…] I have just received from New York a letter which moved me deeply; it is from a young American musician [Jerome Hopkins — see the next letter] who asks me to write to him, because he is having difficulties with his career and is overcome with sadness. He is writing to the wrong person if he is looking for someone to console him, but I will do my best to reply to him.. […]

To Edward Jerome Hopkins (CG no. 2696; 6 February 1863) (see the previous letter)

[…] You probably have a very wrong idea of what life is like for artists in Paris (those worthy of the name). If New York is for you the Purgatory of musicians, for I who know it Paris is their Hell. So do not be too discouraged. […]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 2698; 3 March 1863)

[…] Louis [Berlioz’s son] has gone back to his ship, and hopes soon to be a captain. He is now in Mexico, and ready to leave for France where he will be in a month’s time. […]

To Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray (CG no. 2718; end April 1863)

[…] A young American [Jerome Hopkins — see above] wrote to me recently from New York, and among his confessions he declared that one of his dreams would be to see me reorchestrate Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, particularly the storm — “with your special knowledge of brass instruments, he said, you would turn this movement into an immortal monument”. You need to be born on the banks of Lake Ontario to have such monstrous ideas! I was furious. […]

To his brother-in-law Camille Pal (CG no. 2840; 1 March 1864)

[…] I am asked for a few scenes from Roméo et Juliette for the last concert of the Conservatoire.

The same work has just been performed at Basel in Switzerland, Harold en Italie in Weimar, Le Carnaval romain in Vienna, and again Harold en Italie in New York.

That is all I know; fortunately, I am not hearing any of this, because with very few exceptions the performances are unlikely to be marvellous. […][Note: Harold en Italie was performed for the first time in the United States on 9 May 1863, by the Brooklyn Philharmonic Society conducted by Theodore Thomas, with E. Mollenhauer as solo viola]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 2856; 4 May 1864)

[…] Our Harold has been performed again with great success in New York… What is going through the head of these Americans? [ …]

To Grand-Duke Carl Alexander of Sax Weimar (CG no. 2857; 12 May 1864)

[…] A few of my works are performed far away, in several cities in Germany, in England, in America, and elsewhere. I have composed four operas which are not played anywhere. […]

To princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein (CG no. 2871; 3 August 1864)

[…] If I was not so ill, I would climb on the ship of which my son is captain, and I would go to Mexico. But when it is not possible to cross the Atlantic, it is better to stay in our beautiful Paris, which is becoming more beautiful every day, and is all green and radiant. […]

To Madame Estelle Fornier (CG no. 2970; 20 January 1865)

[…] I have been sent an American newspaper which contains a delightful article on the performance of my overture le Roi Lear in New York. […]

[Note: Le Roi Lear, which was performed for the first time in New York in 1846, was played on 17 December 1864 by the New York Philharmonic Society conducted by Theodore Eisfeld; see also the following letters]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 2973; 25 January 1865)

[…] I have just been sent an American newspaper which contains a very fine article on the performance in New York of my overture le Roi Lear, sister of the overture I just mentioned [les Francs-Juges]. What a pity not to live a hundred and fifty years! One might get the better in the long run of these scoundrels and cretins! […]

To De La Chapelle (CG no. 2979; 26 February 1865)

[…] At the request of M. Weber, son of the illustrious author of Der Freischütz, I looked in vain for a publisher who would dare to publish the memoirs of this great master: but nobody wanted the book. You must not forget that we are in Paris, where music is regarded very much as it is among the Sioux, the Pawnies and the Blackfoot tribe of America.[…]

To princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein (CG no. 2982; 20 March 1865)

[…] I am now performed frequently in St Petersburg, Berlin, Vienna, Copenhagen, New York, Bordeaux, and even in Paris. […]

Have you read the story of the discovery made not long ago, on the banks of the Mississipi, of a valley called the Badlands? They discovered there mountains of bones of prehistoric animals, lying dead in a heap there, from the time of the last cataclysm. None of those species exists anymore, with the exception of the rhinoceros.

What a glorious survivor!

Who among us will be able to flatter himself of being a rhinoceros?

To his nieces Nancy and Joséphine Suat (CG no. 3032; 11 August 1865)

[…] A good deal of my music is now performed in Russia, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and in America; there are people who adore me whom I shall never know .[…]

To Madame Estelle Fornier (CG no. 3057; 4 November 1865)

[…] They are announcing performances of several of my works at concerts in Brussels, Vienna, Dresden, Boston, and New York. […]

To Adolphe Samuel (CG no. 3076; 3 January 1866)

[…] I am still unwell and increasingly indifferent from day to day to what is going on in our musical world. But I admit that it was a great pleasure for me to learn that my Harold symphony was performed with great precision and verve in Moscow and New York. These are peoples who are new to music and who are fond of saying: Go to the head ! […]

To his nieces Joséphine and Nancy Suat (CG no. 3211; 11 January 1867)

[…] I am asked from New York to suggest a sculptor to carve a bust of myself which they want to display in an immense concert hall which has just been built. Here is the real proof that I am dead. There cannot be any doubt about it now. And yet the dead do not experience any pain... […]

[On the bust of Berlioz by Jean-Joseph Perraud which was ordered by Theodore Steinway for the Steinway Hall in New York, see below the letters CG nos. 3279, 3283, 3284, 3286, 3346. Steinway Hall had been opened the previous year at 14th Street, New York; the main hall had a capacity of 2000 and became the seat of the New York Philharmonic until the opening of Carnegie Hall in 1891]

To Auguste Morel (CG no. 3241; 12 May 1867)

[…] The day before yesterday there was a performance of L’Enfance du Christ in Copenhagen; it was played a month earlier at Lausanne in Switzerland. My works are performed almost everywhere now, except in Paris. And yet Pasdeloup massacres here some of my pieces from time to time.

Louis is still in Mexico. […]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 3244; 11 June 1867)

[…] A few days ago I was pressed by some Americans to go to New York, where according to them I am very popular. Last year our symphony Harold en Italie was performed there five times, with increasing success and Viennese applause. […]

To Madame Estelle Fornier (CG no. 3245; 15/16 June 1867)

[…] I have received on a number of occasions some very tempting offers from several Americans who would like me to go to New York, where they claim that I am very popular. But I am not in a position to undertake such a journey, and I have refused all their offers. […]

To Theodore Steinway (CG no. 3278; 25 September 1867)

[…] I have just heard the magnificent instruments which you brought to us from America and which come from your workshops. Allow me to compliment you on the fine and rare qualities which these pianos possess. […] This is one great improvement among others which you have introduced in the manufacture of the instrument, an improvement for which all artists and music-lovers gifted with a sensitive ear will be infinitely grateful to you. […]

To his niece Nancy Suat (CG no. 3279; 29 September 1867)

[…] I have had another proposal from Steinway, the wealthy piano-manufacturer from New York; the day before yesterday he came before his departure to ask me go to America at least next year, and do you know what he offered me?...

ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND FRANCS!

Just about time, now that I am good for nothing!

And yet I will try to do something good in Russia. Ah! if only I had the energy.

I am due to go later today to the Institut to agree with my colleague Perrot [sic for Perraud] who is going to make a marble bust of myself for M. Steinway. It will then be cast in bronze for the great hall in New York. These gentlemen have come to an agreement on the costs of this bust. […][On the bust of Berlioz by Perraud see above CG no. 3211. The bust is still extant in New York, and there are copies of it in St Petersburg (see CG no. 3346), at the Hector Berlioz Museum in La Côte-Saint-André, and at the Institut. See the image in the top left corner of this page]

To Madame Estelle Fornier (CG no. 3283; 4 October 1867)

[…] Everything is coming my way now that I no longer have the strength. Present in Paris was also a wealthy American piano-manufacturer [Steinway], who two months ago had already made me glittering offers to entice me to go to New York, though I refused them. On learning that I was accepting the Russian proposal he came back yesterday to renew his offer. « Do come at least new year, he said to me, and remember that for six months spent in New York I am offering you one hundred thousand francs. »

While waiting for me to make up my mind, he is having a bronze bust of myself made here, which is to go in a magnificent hall which he has just built for concerts in New York; everyday I go to pose for the sculptor [Perraud]. […]

To Lambert and Aglaé Massart (CG no. 3284; 4 October 1867)

[…] Let me tell you also that an American, whose offers I had declined a month and a half ago, on learning that I was accepting the offers from the Russians, came back three days ago to offer me one hundred thousand francs if I was willing to go to New York next year. What do you say about this? In the meantime he is having a bronze bust of myself made for a magnificent hall which he has built over there, and everyday I go to pose for it. If I was not so old, all this would give me pleasure. […]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 3286; 8 October 1867)

[…] The Grand-Duchess Helen of Russia was recently in Paris […] She asked me to come to St Petersburg next month to conduct six concerts at the Conservatoire, of which one would be composed exclusively of my music. […]

On the other hand I refused, and obstinately, the urgent request of an American impresario who came to offer me one hundred thousand francs to go to spend six months in New York. Out of pique this worthy gentleman has had a bust of myself made, in bronze and larger than life, to place it in a hall which he has just built in America. As you can see, everything comes your way when you wait long enough and are more or less fit for nothing. […]

To princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein (CG no. 3296; 27 October 1867)

[…] I have had news from Meiningen through three people: a German, who wrote to me about the love scene, the adagio from Roméo et Juliette, an American who was at the festival, and Gasperini the critic who was also there. Without that I would not have heard about it. Almost everything is now a matter of indifference to me. […]

To Vladimir Stasov (CG no. 3346; 1 March 1868)

[…] Yesterday I dragged myself to the Académie where I saw my sculptor and colleague Perrot [Perraud]. He informed me that Steinway the American had at last paid him for my bust and that they are busy at the moment casting three copies larger than life for New York and Paris. I believe it is you who expressed the wish to have a bronze copy for the Conservatoire of St Petersburg. If it was not you, it was Kologrivov, or Cui, or Balakirev. In any case pass on to them the information that M. Perrot told me that it was possible to cast more copies of this bust and that the casting would cost 280 fr. Write to me at no. 4 rue de Calais in Paris. […]

![]()

The table below has been compiled from a number of sources: concert programmes in our collection (reproduced below), the entries for performances of individual works of Berlioz in Holoman’s Catalogue (pp. 43, 51, 105, 189, 202, 240, 243, 256, 263, 269, 274, 296), and the Appendix in Saloman (Selected Performances of Hector Berlioz’s Works in New York, 1846-90), pp. 210-15. The table below does not claim to be complete, and there are some discrepancies between the listings of Holoman and of Saloman. It is likely to need some corrections and additions. For a commentary on these performances see above.

The following abbreviations have been used: Carnaval romain = Ouverture du Carnaval romain, Corsaire = Ouverture du Corsaire, Francs-Juges = Grande Ouverture des Francs-Juges, Invitation = Weber, L’Invitation à la valse orchestrated by Berlioz, Marche marocaine = Léopold de Meyer, Marche marocaine arranged and orchestrated by Berlioz, Marche hongroise = Marche hongroise from la Damnation de Faust, Marche d’Isly = Léopold de Meyer, Marche d’Isly orchestrated by Berlioz, Roi Lear = Grande Ouverture du Roi Lear, Roméo = Roméo et Juliette, Waverley = Grande Ouverture de Waverley.

|

![]()

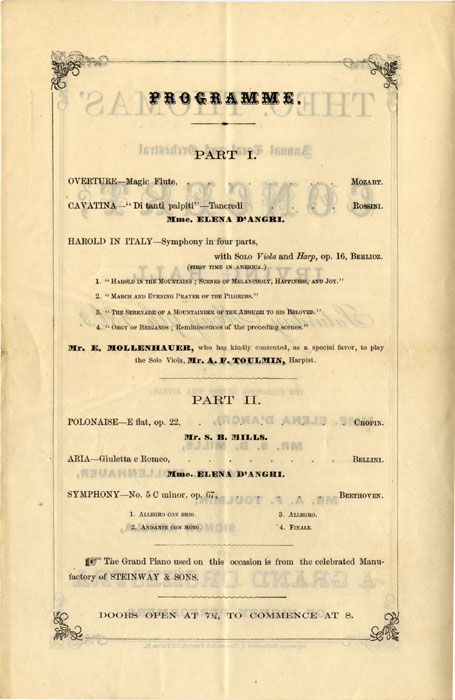

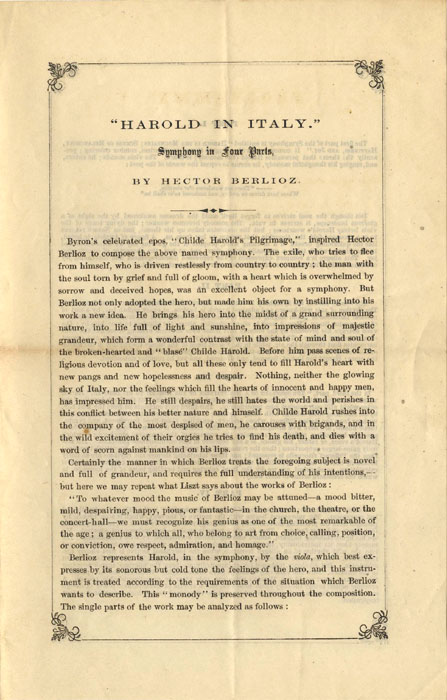

The programme note for the concert at which Harold en Italie received its first performance in America (9 May 1863) under Theodore Thomas is of special interest (see the image below). The conductor evidently wished to give the occasion special prominence, not only by emphasising his own role, but by having a detailed (though unsigned) note written to introduce the Berlioz symphony (whereas the other items did not receive similar treatment). The note, transcribed in full below as it stands, brings out implicity the similarities between Harold en Italie and La Damnation de Faust: in both cases a wandering observer witnesses contrasted scenes from the world around him, but is unable to find solace in them.

“HAROLD IN ITALY.”

Symphony in four Parts.

BY HECTOR BERLIOZ

Byron’s celebrated epos, “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”, inspired Hector Berlioz to compose the above named symphony. The exile, who tries to flee from himself, who is driven restlessly from country to country ; the man with the soul torn by grief and full of gloom, with a heart which is overwhelmed by sorrow and deceived hopes, was an excellent subject for a symphony. But Berlioz not only adopted the hero, but made him his own by instilling into his work a new idea. He brings his hero into the midst of a grand surrounding nature, into life full of light and sunshine, into impressions of majestic grandeur, which form a wonderful contrast with the state of mind and soul of the broken-hearted and “blasé” Childe Harold. Before him pass scenes of religious devotion and of love, but all these only tend to fill Harold’s heart with new pangs and new hopelessness and despair. Nothing, neither the glowing sky of Italy, nor the feelings which fill the hearts of innocent and happy men, has impressed him. He still despairs, he still hates the world and perishes in this conflict between his better nature and himself. Childe Harold rushes into the company of the most despised of men, he carouses with brigands, and in the wild excitement of their orgies he tries to find his death, and dies with a word of scorn against mankind on his lips.

Certainly the manner in which Berlioz treats the foregoing subject is novel and full of grandeur, and requires the full understanding of his intentions, — but here we may repeat what Liszt says about the works of Berlioz :

“To whatever mood the music of Berlioz may be attuned — a mood bitter, mild, despairing, happy, pious, or fantastic — in the church, the theatre, or the concert-hall — we must recognize his genius as one of the most remarkable of the age ; a genius to which all, who belong to art from choice, calling, position, or conviction, owe respect, admiration, and homage.”

Berlioz represents Harold, in the symphony, by the viola, which best expresses by its sonorous but cold tone the feelings of the hero, and this instrument is treated according to the requirements of the situation which Berlioz wants to describe. This “monody” is preserved throughout the composition. The single parts of the work may be analyzed as follows :

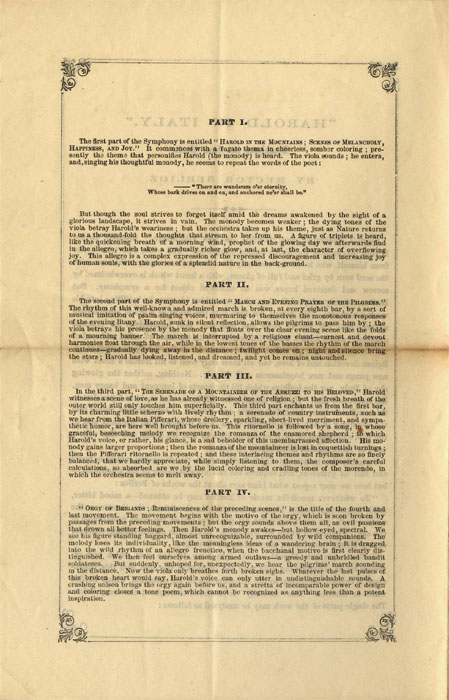

PART I.

The first part of the Symphony is entitled “HAROLD IN THE MOUNTAINS ; SCENES OF MELANCHOLY, HAPPINESS, AND JOY.” It commences with a fugato thema in cheerless, somber coloring ; presently the theme that personifies Harold (the monody) is heard. The viola sounds ; he enters, and, singing his thoughtful monody, he seems to repeat the words of the poet :

— “There are wanderers o’er eternity,

Whose bark drives on and on, and anchored ne’er shall be.”

But though the soul tries to forget itself amid the dreams awakened by the sight of a glorious landscape, it strives in vain. The monody becomes weaker ; the dying tones of the viola betray Harold’s weariness ; but the orchestra takes up his theme, just as Nature returns to us a thousand-fold the thoughts that stream to her from us. A figure of triplets is heard, like the quickening breath of a morning wind, prophet of the glowing day we afterwards find in the allegro, which takes a gradually richer glow, and, at last, the character of overflowing joy. This allegro is a complex expression of the repressed discouragement and increasing joy of human souls, with the glories of a splendid nature in the back-ground.

PART II.

The second part of the Symphony is entitled “MARCH AND EVENING PRAYER OF THE PILGRIMS.” The rhythm of this well-known and admired march is broken, at every eighth bar, by a sort of musical imitation of psalm-singing voices, murmuring to themselves the monotonous responses of the evening litany. Harold, sunk in silent reflection, allows the pilgrims to pass him by ; the viola betrays his presence by the monody that floats over the clear evening scene like the folds of a mourning banner. The march is interrupted by a religious chant — earnest and devout harmonies float through the air, while in the lowest tones of the basses the rhythm of the march continues — gradually dying away in the distance ; twilight comes on ; night and silence bring the stars ; Harold has looked, listened, and dreamed, and yet he remains untouched.

PART III.

In the third part, “THE SERENADE OF A MOUNTAINEER OF THE ABRUZZI TO HIS BELOVED,” Harold witnesses a scene of love, as he has already witnessed one of religion ; but the fresh breath of the outer world still only touches him superficially. This third part enchants us from the first bar, by its charming little scherzo with lively rhythm ; a serenade of country instruments, such as we hear from the Italian Pifferari, whose drollery, sparkling, short-lived merriment, and sympathetic humour, are here well brought before us. This ritornello is followed by a song, in whose graceful, beseeching melody we recognize the romanza of the enamored shepherd ; to which Harold’s voice, or rather, his glance, is a sad beholder of this unembrassed affection. His monody gains larger proportions ; then the romanza of the mountaineer is lost in coquettish turnings ; then the Pifferari ritornello is repeated ; and these interlacing themes and rhythms are so finely balanced, that we hardly appreciate, while simply listening to them, the composer’s careful calculations, so absorbed are we by the lucid colorings and cradling tones of the morendo, in which the orchestra seems to melt away.

PART IV.

“ORGY OF BRIGANDS ; Reminiscences of the preceding scenes,” is the title of the fourth and last movement. The movement begins with the motivo of the orgy, which is soon broken by passages from the preceding movements ; but the orgy sounds above them all, as evil passions that drown all better feelings. Then Harold’s monody awakes — but hollow-eyed, spectral. We see this figure standing haggard, almost unrecognizable, surrounded by wild companions. The melody loses its individuality, like the meaningless ideas of a wandering brain ; it is dragged into the wild rhythm of an allegro frenetico, when the bacchanal motivo is first clearly distinguished. We then feel ourselves among armed outlaws — a greedy and unbridled bandit soldatesca. But suddenly, unhoped for, unexpectedly, we hear the pilgrim’s march sounding in the distance. Now the viola only breathes forth sighs. Whatever the last pulses of this broken heart would say, Harold’s voice can only utter in indistinguishable sounds. A crashing unison brings the orgy again before us, and a stretta of incomparable power of design and coloring closes a tone poem, which cannot be recognized as anything less than a potent inspiration.

![]()

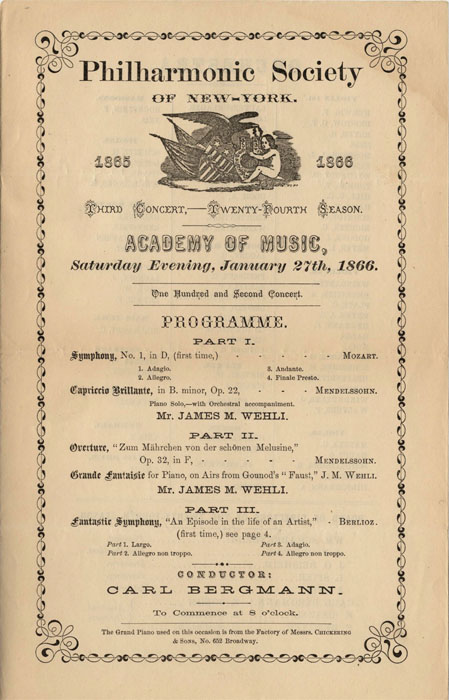

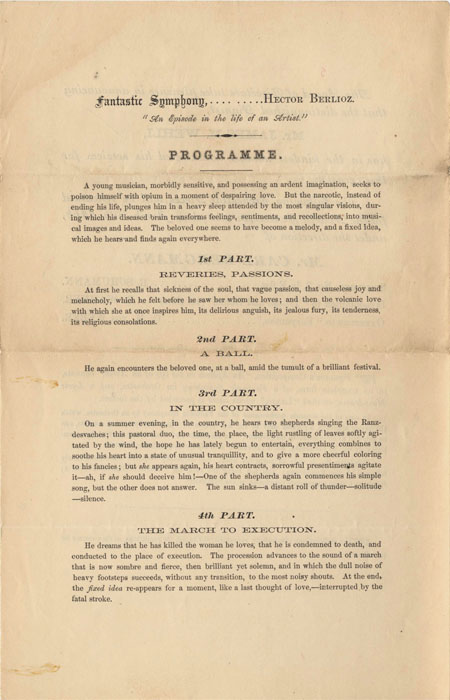

The following programme note for the performance of the Symphonie fantastique on 27 January 1866 under Carl Bergmann is transcribed from the image of the programme (reproduced below). It is much less original than that for Harold en Italie transcribed above: it is simply a translation of the programme for the symphony that Berlioz published in 1855, with the omission of the programme for the last movement which was not performed at this concert.

Fantastic Symphony,……….HECTOR BERLIOZ

“An Episode in the life of an Artist.”

PROGRAMME

A young musician, morbidly sensitive, and possessing an ardent imagination, seeks to poison himself with opium in a moment of despairing love. But the narcotic, instead of ending his life, plunges him in a heavy sleep attended by the most singular visions, during which his diseased brain transforms feelings, sentiments, and recollections, into musical images and ideas. The beloved one seems to have become a melody, and a fixed idea, which he hears and finds again everywhere.

1st PART.

REVERIES, PASSIONS.

At first he recalls that sickness of the soul, that vague passion, that causeless joy and melancholy, which he felt before he saw her whom he loves ; and then the volcanic love with which she at once inspires him, its delirious anguish, its jealous fury, its tenderness, its religious consolations.

2nd PART.

A BALL.

He again encounters the beloved one, at a ball, amid the tumult of a brilliant festival.

3rd PART.

IN THE COUNTRY.

On a summer evening, in the country, he hears two shepherds singing the Ranz-desvaches [sic]; this pastoral duo, the time, the place, the light rustling of leaves softly agitated by the wind, the hope he has lately begun to entertain, everything combines to soothe his heart into a state of unaccustomed tranquillity, and to give a more cheerful coloring to his fancies ; but she appears again, his heart contracts, sorrowful presentiments agitate it — ah, if she would deceive him ! — One of the shepherds commences again his simple song, but the other does not answer. The sun sinks — a distant roll of thunder — solitude — silence.

4th PART.

THE MARCH TO EXECUTION.

He dreams that he has killed the woman he loves, that he is condemned to death, and conducted to the place of execution. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is now sombre and fierce, then brilliant yet solemn, and in which the dull noise of heavy footsteps succeeds, without any transition, to the most noisy shouts. At the end, the fixed idea re-appears for a moment, like a last thought of love, — interrupted by the fatal stroke.

![]()

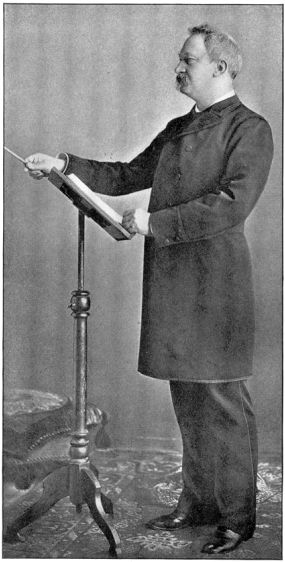

Portraits of conductors

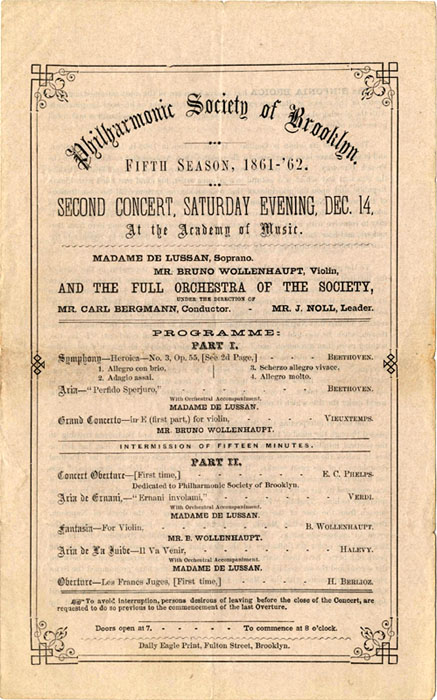

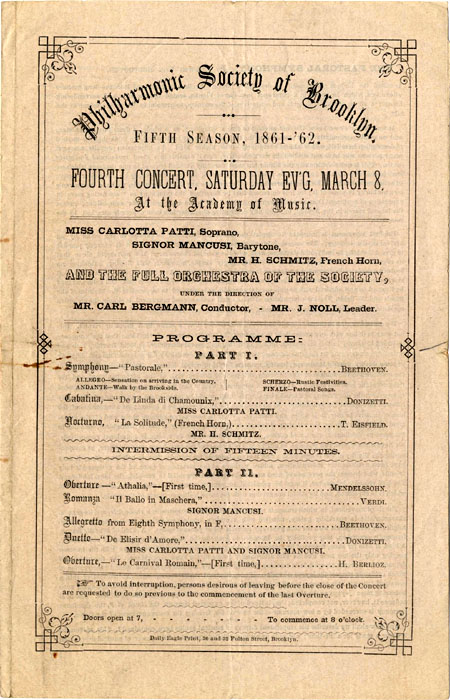

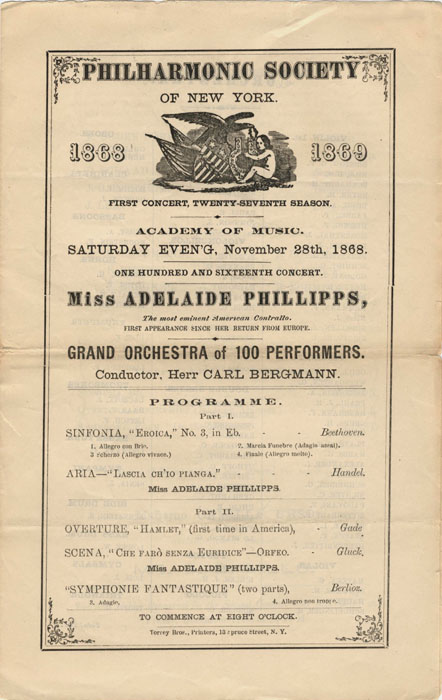

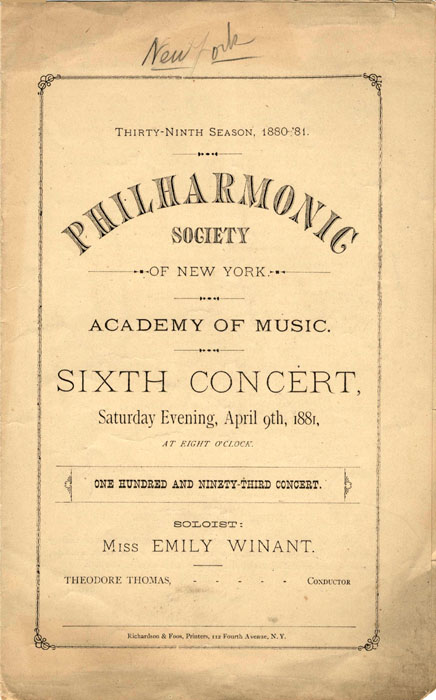

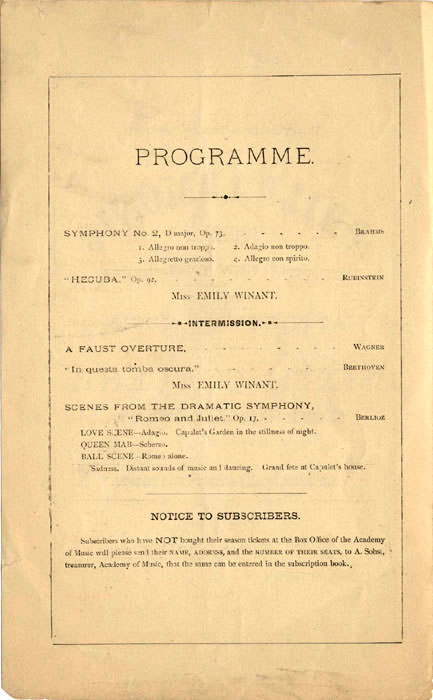

Concert programmes — in Berlioz’s lifetime

Concert programmes

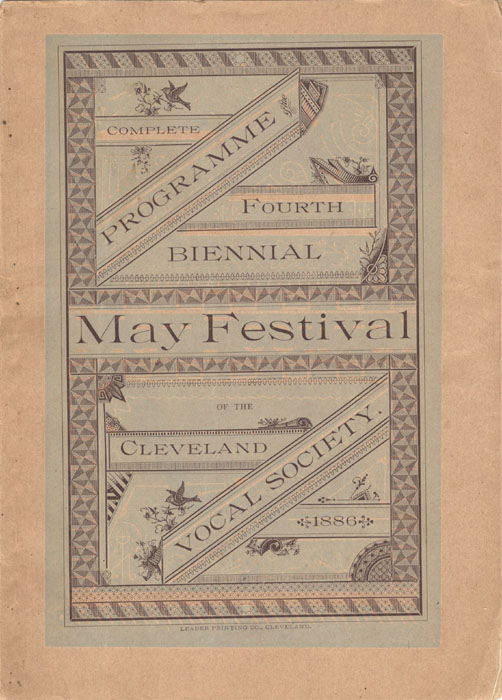

— after his death

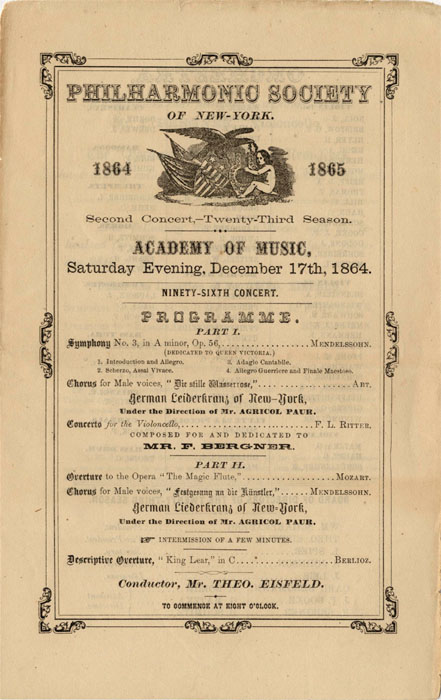

On Theodore Eisfeld see above.

On Carl Bergmann see above.

On Theodore Thomas see above.

On Leopold Damrosch see above.

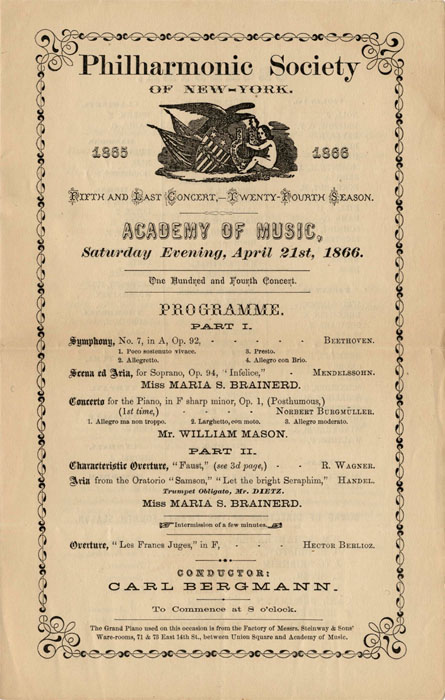

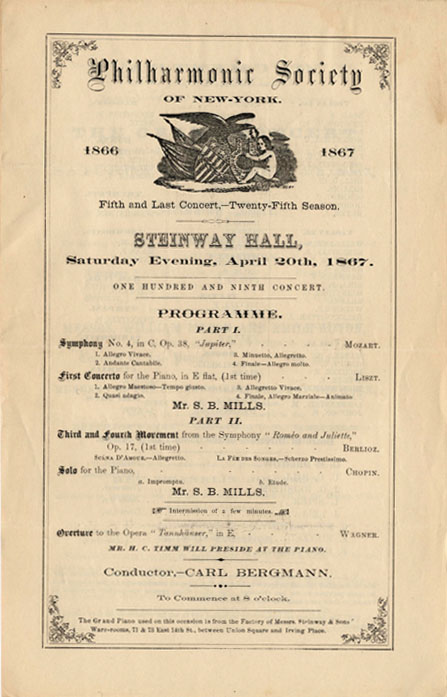

The concert programmes reproduced in the two sections below, in chronological sequence, are all from our own collection. They have been donated by us to the Hector Berlioz Museum in La Côte Saint-André. See also above the table of concerts and the commentary on performances of Berlioz in the United States in the 19th century.

See above for the role of Carl Bergmann in promoting the music of Berlioz.

It will be noted that the programme includes a work by Theodore Eisfeld, since 1862 one of the conductors of the Philharmonic Society of Brooklyn.

Note that the piano used for this concert comes from “the celebrated Manufactory of STEINWAY & SONS” .

See above for a transcription of the programme note and the role of Theodore Thomas.

See above for Theodore Eisfeld and Berlioz.

See above for a transcription of the programme.

This concert was given in Steinway Hall which had opened in 1866.

Note how the conductor is referred to here as ‘Herr CARL BERGMANN’

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; Berlioz and the Americas page created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 1 December 2018, updated on 1 January 2019.

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the texts and images on Berlioz and the Americas page. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Berlioz and the Americas — Concert programmes of the 20th century

Berlioz and the Americas — Concert programmes of the 20th century