![]()

Introduction

Exposition Universelle and the Palais de l’Industrie in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

In 1855 Berlioz participated in two ways in the Exposition Universelle, first as member of a jury which assessed musical instruments at the exhibition, then as organiser and conductor of three large-scale concerts.

The Exposition Universelle of 1855, held on the Champs-Élysées in Paris from 15 May to 15 November, was designed by Napoleon III as the counterpart to London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, the first of its kind, and the monumental Palais de l’Industrie was constructed in emulation of London’s Crystal Palace. Prince Napoleon, the cousin of the emperor, was in overall charge of the organisation of the exhibition, which attracted vast crowds. Berlioz participated in both exhibitions in the first instance as member of an international jury which was set up to assess the musical instruments exhibited by their manufacturers (our English translation of his report on his work in 1851 is reproduced elsewhere on this site, as is the original French text).

His work as juror in 1855 kept Berlioz busy for much of August and September, and he eventually published his report in the form of feuilletons in the Journal des Débats in three instalments, on 9 January, 12 January and 15 January 1856. Berlioz lists in the second of these articles the medals awarded to the successful contestants; we possess in our collection the two medals that were awarded to the manufacturers Alexandre père et fils.

Work on the jury service was arduous and time-consuming, and few letters of Berlioz have survived for this period, but they give glimpses of his activity as juror. First a letter to the poet Heinrich Heine, written on receipt of his recently-published collection entitled Poèmes et Légendes (CG no. 2001, 16 August):

[…] Forgive me for not having already come to thank you for your delicious and wonderful poems; I have the terrible honour of being a member of the jury for the musical instruments at the Exhibition, and every day, from nine in the morning to five in the afternoon, instead of going to listen to a great poet I am obliged to listen to dreadful pianos and to their even more dreadful manufacturers. But in spite of all I will come to see you, possibly even today if our forced labour is limited to the audition of a mere fifty instruments. […]

Then a fortnight later to his sister Adèle (CG no. 2009, 2 September):

[…] We are making progress in this deadly chore of assessing musical instruments, though it is going to keep us busy for at least another week. And what scenes now! what fury! what despair! The exhibitors are coming to blows in the foyer of the Conservatoire while we are holding our sessions; they scream that this is barbaric, that we want to ruin the famous companies and raise new ones on their ruins! Mme Érard is in despair.

The day before yesterday Halévy, who has relatives with interests in Pleyel’s business, wanted us to state that we had placed Pleyel hors concours because he is too far above the others, when the exact opposite is the truth. To get the others to share my views I had to speak out vigorously against this strange proposal, and Fétis was the only one to give me support. In the end justice and commonsense prevailed.

« That is what happens, Halévy was saying naïvely, when you audition instruments without knowing who made them! »

This is putting a spanner in the works of many, but everyone supports our view. […]

Finally, to the composer Camille-Marie Stamaty (CG no. 2029bis, late September):

[…] I would now be [at St Valéry en Caux] if the Jury of the Exhibition had not reduced me to slavery. We have auditioned 387 pianos, at least 400 brass instruments, without counting loads of flutes, bundles [fagots] of oboes and other bundles that are still commonly referred to as bassoons [a play on the German word for bassoon, Fagott], and bleating flocks of melodiums and harmoniums; we are now exposed to the wind of organs and of calumny. We will have suffered torment for two months, and that is the only recompense we will receive. […]

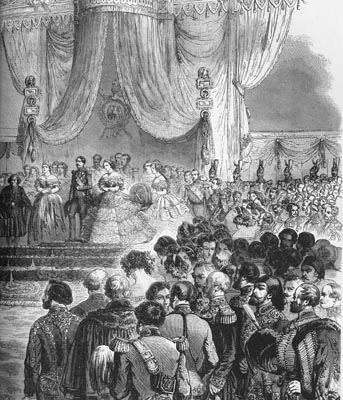

With the completion of his work as juror Berlioz may have imagined that his participation in the Exhibition was at an end. But late in the day there was a new development: Berlioz was asked by Prince Napoleon to organise three large concerts as well, as he writes to his sister Adèle the following month (CG no. 2035, 21 October):

[…] I am taking advantage of a moment of leisure to write to you; I will not enjoy any for a long time to come. Prince Napoleon summoned me yesterday and suggested that I take charge of the organisation and direction of a concert of Babylonian proportions which is to take place at the Palais de l’Exposition on 15 November, the day of the distribution of prizes by the Emperor. I asked that I should be given enough time; it involves an orchestra of 1000 musicians, and the Prince then called all the staff of the Imperial Commission to decide on the spot on the main questions, and this done said to them: « Gentlemen, you see that M. Berlioz is kind enough to take charge of this vast undertaking; we are therefore all agreed that as far as the music is concerned everyone here is under his orders. »

The expenses are being met not by the government but by an entrepreneur [Ernest Ber], who was not prepared either to take on this burden without my collaboration.

There will be three concerts, two of them after that of the ceremony. […]

The large programme selected by Berlioz included excerpts from his own music: three movements from the Te Deum (Te Deum laudamus, Tibi omnes, and the concluding march), which had received its first performance earlier that year at Saint-Eustache, the last movement (Apothéose) of the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale, and the cantata in honour of Napoleon III, L’Impériale which now received its first performance. Also included were the overture to Weber’ Der Freischütz, a scene from Gluck’s Armide, the last three movements of Beethoven’s fifth symphony, the prayer from Rossini’s Moïse en Égypte, the Blessing of the Daggers from eyerbeers’s Les Huguenots, Mozart’s Ave verum and the chorus ‘See the conquering hero’ from Handel’s Judas Maccabæus. This programme should be compared with that of the similarly grand concert he gave at the Festival de l’Industrie a decade earlier, on 1 August 1844. In the 1855 concerts, the full programme was only performed at the concert on 16 November, the day after the ceremony when there was only time for part of L’Impériale and the Apothéose; the whole programme was repeated at the third concert on 24 November.

A glimpse of the vast preparations involved is provided in a letter of Berlioz to Princess Sayn-Wittgentsein dated 6 November (CG no. 2044):

[…] You know what a furnace I am roasting in at the moment… I have to direct and organise the musical part of the festival which will take place at the Palais de l’Exposition on the 15th of this month, for the distribution of prizes by the Emperor. In addition there will be two public performances of this immense concert, which involves 1200 musicians. Yesterday I embarked on my rehearsals and my battles with the architects, the copyists, etc., etc. I have another nine days ahead of me, with my baton in my hand from nine in the morning till four in the afternoon, and I have to hold special rehearsals for each vocal or instrumental part. […]

Berlioz later devoted a paragraph of his Memoirs to an account of the concerts (Memoirs, Postface); his correspondence provides further details. After the first two concerts he wrote to Liszt (CG no. 2046, 17 November), and on the same day in similar terms to his sister Adèle (CG no. 2047):

[…] I am writing these six lines to tell you that I am now in command of two victorious battles. Yesterday and the day before my huge orchestra worked like a quartet.

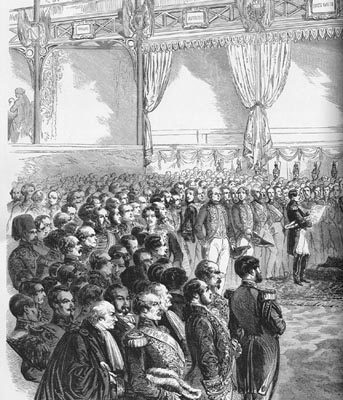

Yesterday in particular, before a crowd such as has never been seen in Paris. (The receipts amounted to over sixty thousand francs!) As for the magnificence of the imperial ceremony, the sight of this Babylonian hall decorated like the palace of Aladdin; and as for the sight of this audience of forty thousand spectators, these uniforms from every country arranged in tiers on a triple amphitheatre, these chandeliers, these trophies, this buzz of enthusiasm which rolled like the sound of the sea — I will not attempt to convey this to you.

I know that the emperor and Prince Napoleon, who were so apprehensive about the success of my project, are very satisfied. I will probably be seeing the Prince this evening at the reception given by the Prefect of the Seine.

I am worn out, exhausted, and move like a sleepwalker. […]

After the third concert Berlioz wrote again to Liszt briefly: ‘The last concert was magnifique. Thanks to my electric metronome I literally held in my hand this immense musical mammoth’ (CG no. 2056, 30 November). The reference is to the electric metronome he used to maintain the ensemble with several sub-conductors. The device had been newly created by the Belgian inventor Verbrugghen, who had come from Brussels to Paris at Berlioz’s request to install the equipment. The use of this instrument was seized upon by the press: a cartoon in the satirical paper Charivari of 2 December 1855 depicts ‘M. Berlioz making use of his electric baton to conduct an orchestra with the players located in all the regions of the globe’.

A letter of Berlioz to his brother-in-law Marc Suat comments on the general success of the three concerts (CG no. 2057, 2 December):

[…] I am still feeling rather lame and sick because of the dreadful fatigue caused by the concerts of the Exhibition. The last one was splendid; never in France, nor anywhere else probably, has such a performance by such a multitude of musicians been heard. News of the success spread far away, to all the corners of Europe. This was brilliantly vouched for by the papers Le Constitutionnel, le Pays, La Patrie, Les Débats, La Gazette Musicale, and La Presse. As it usually does, Le Siècle wrote an article both sour and flat. At all three sessions the musicians gave me a huge ovation. At the Prefect’s reception Prince Napoleon came to shake my hand; I know since yesterday that he put forward my name to the Emperor for the cross of Officer of the Légion d’honneur. […]

In the event Berlioz had to wait many years for the award: it was only given to him in August 1864.

![]()

All the pictures reproduced on this page have been scanned from 19th century engravings, photos, newspapers (notably 1855 issues of L’Illustration), books, medals and other items in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

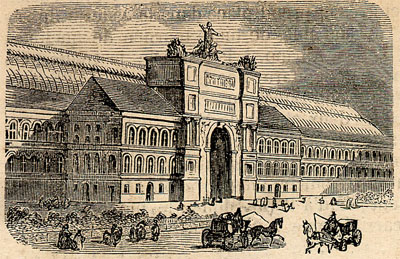

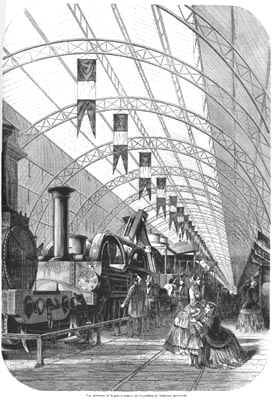

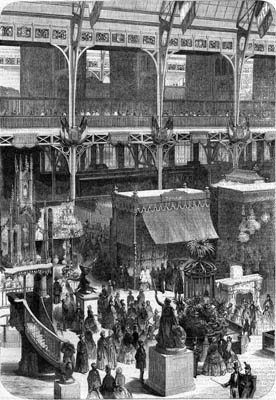

The Palais de l’Industie was built in 1853 by the architect Vial, on an open space used until then for recreational activities, to house the 1855 Universal Exhibition. It was an imposing building of 200 meters long, 47 wide and 35 high, with 408 windows, facing the Elysée palace, on what is now partly occupied by the Avenue Alexandre-III. Inaugurated on 1st May 1855, the building was also used later for the Universal Exhibitions of 1878 and 1898, and then was used until 1897 for various other exhibitions and public celebrations. It was demolished for the Universal Exhibition of 1900; part of the Grand-Palais, the Petit-Palais, Place Georges-Clemenceau and the Avenue Alexandre-III now occupy its site (from Jacques Hillairet, Dictonnaire historique des rues de Paris, vol. A/K, p. 299).

The above engraving was published in Le Monde Illustré on 5 March 1859.

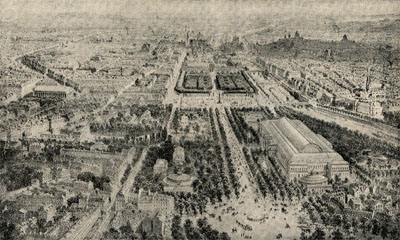

This 1860 engraving has been scanned from Jacques Hillairet, Dictonnaire historique des rues de Paris, vol. A/K, p. 298.

This 1860 engraving has been scanned from Harmsworth History of the World, volume VII (London, 1909, p. 5017). It shows the Palais de l’Industrie by the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, leading up to Place de la Concorde (and its Egyptian obelisk from Luxor), and beyond it the Tuileries Gardens and the Louvre. The Madeleine can also be seen in the picture, to the left of Place de la Concorde.

This picture has been scanned from John L. Stoddards Lectures, Volume V – Paris La Belle France and Spain, by John L. Stoddard (Balch Brothers, 1898).

This lithograph was designed and engraved by Philippe Benoist and Auguste Bayot, and published by Nantes, Lith Charpentier Edit – Paris Quai des Augustins, 55.

Front |

Back |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Front |

Back |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

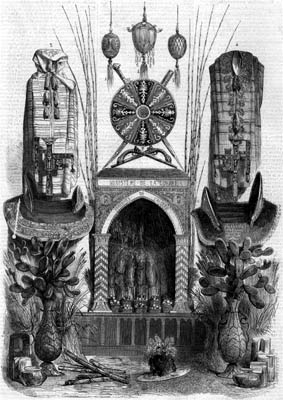

The text on the emblem reads:

on the outer circle: MULL A LA SUISSE

on the inner circle: EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE AGRICULTURE INDUSTRIE BEAUX ARTS PARIS 1855

This emblem could have been cut out from a programme, or something official; the name of the lady who owned it, and who was the great-grand-mother of the person from whom we purchased the item, is written on the back.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.