Berlioz at the 1851 Exhibition

Illustrations:

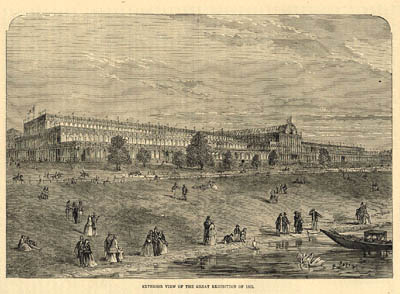

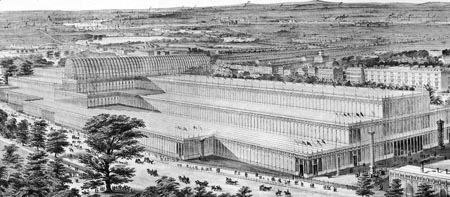

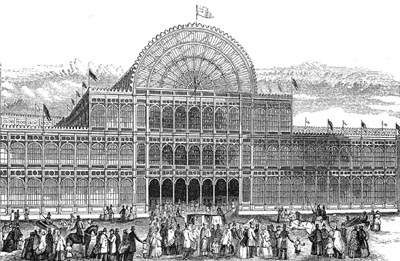

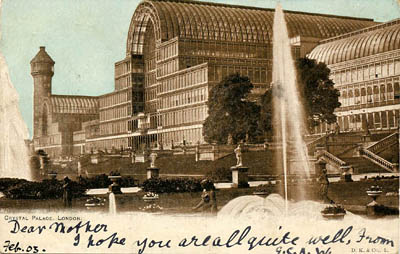

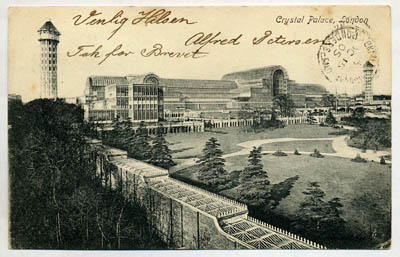

Crystal Palace in Hyde Park

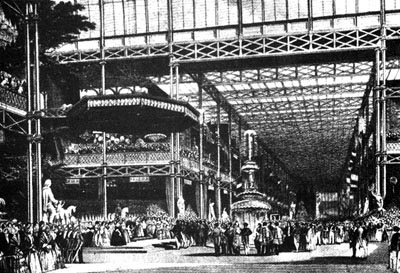

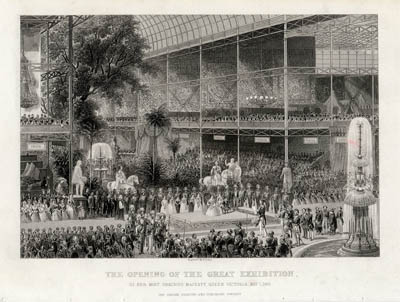

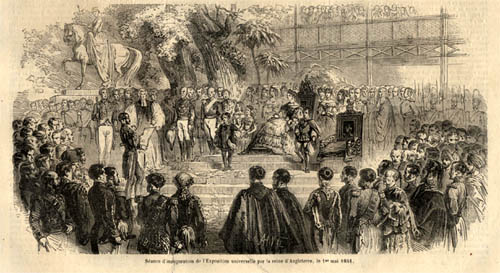

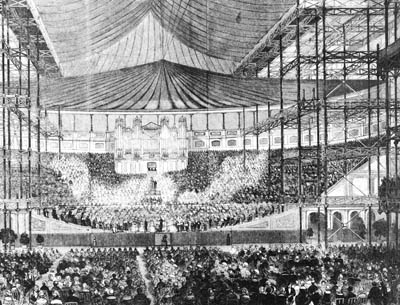

Opening ceremony of the Exhibition

Crystal Palace in Sydenham

Great Exhibition memorabilia

This page is also available in French

![]()

In April 1851 Berlioz was appointed by the Minister of Agriculture and Trade to serve as representative of France on the international commission examining musical instruments at the celebrated Universal Exhibition in London. He stayed there from May till the end of July.

The Exhibition Palace, nicknamed Crystal Palace by the satirical magazine Punch because of the enormous amount of glass used in its construction, was erected in Hyde Park. Ever since the hall has been known as Crystal Palace. The building that housed the Great Exhibition was proposed by Prince Albert (Queen Victoria’s husband), and designed by Joseph Paxton. The Exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria on 1 May 1851; it closed on 11 October of the same year. The Exhibition Palace was dismantled in 1852 and later re-erected in Sydenham, in South London, as a sporting and cultural venue until it was burnt down by fire in 1936.

The task of the Jury of which Berlioz was a member was very intensive and their daily schedule quite full; they had to listen to hundreds of musical instruments of all sorts exhibited by many countries from around the world – East as well as West. The Jury’s job was to give prizes to the best in each category. In June Berlioz wrote to his sister Adèle (Correspondance générale no. 1417, hereafter abbreviated to CG):

[…] I have been in London for a month and a half, very busy with the stultifying job of examining musical instruments sent to the Exhibition. There are days when I am overcome with despondency and feel on the point of returning to Paris. No one could imagine a more dreadful chore than the one for which I have been specially selected. I have to listen to wind and brass instruments. My head is bursting with the sounds of hundreds of wretched contraptions, each more out of tune than the rest, with three or four exceptions.

Apart from this chore my stay in London is very pleasant; I receive invitations from every quarter, from the Lord Mayor, from the Mayor of Birmingham, from compatriots, without counting all the courtesies with which the English are so generous. Then the theatre directors and the concert organisers who have to be humoured as far as possible, and the exhibitors who want to explain something to me. It is only on Sundays that I can catch my breath and go for walks in the countryside. In the midst of all this I have to find time to write long feuilletons for the Journal des Débats; I have already done three, only one of which has appeared. So you will not be surprised that I missed my uncle who came to spend a mere three days here. […] As for meeting in Crystal Palace there was little chance, it is far too immense and crowded.

I am reasonably well paid by the Minister of Trade, though they had the singular meanness of leaving us to pay for our own travel expenses. […]

Today is the first day of warm weather; I was worried I would not see any summer this year. The parks and squares in London are now very pleasant, and as for the surrounding countryside it is delightful and the abundance of vegetation is not to be seen anywhere on the Continent. […]

Berlioz had been wary of the pressures caused by the competition between rival makers from different countries, many of whom were personally known to him (CG no. 1400). A letter to Armand Bertin, the director of the Journal des Débats, refers to these tensions: ‘What we hear every day is pitiful. It is obvious that Érard [pianos] and Sax [wind and brass] are head and shoulders above all their rivals. As a result the English commission would like there to be no grand prix, to avoid the national heart-break of being placed in second or third place’ (CG no. 1414). In the end Berlioz came down categorically in favour of the French makers: ‘France wins over the whole of Europe, with no possible comparison. Érard, Sax and Vuillaume [string instruments]. All the rest belongs to the category of cauldrons, pipes and toy fiddles’ (CG no. 1419; cf. 1424). The same conclusion was openly expressed by Berlioz in the report of the Jury on musical instruments which he wrote up and was eventually published in Paris in 1854 and again in 1855. The full text of this report is reproduced on this site in the original French and in an English translation.

Berlioz was very impressed by the Exhibition itself, as he said to his son Louis in a letter (CG no. 1415, 1 June):

[…] This universal exhibition, the competition of all nations, and especially the vast Crystal Place where everything is exhibited, these are wonders which I will not attempt to describe to you. […]

The whole of the 21st evening in Berlioz’s Les Soirées de l’orchestre is devoted to his experiences in London during his stay in 1851 (this reproduced parts of the five original feuilletons published in the Journal des Débats between May and August 1851). He has very little to say of his role as judge of musical instruments on the Jury, but concentrates on more picturesque aspects, such as the Great Exhibition itself, musical life in London, and the exotic music (especially Chinese) that was to be heard at the Exhibition from various parts of the world. But pride of place in his narrative goes to the extraordinary experience he had at the Anniversary Meeting of the Charity Children which he heard at St Paul’s Cathedral one evening, sung by a chorus of 6500 children. He went home after the concert but was so moved that he was unable to get to sleep and decided to get up and walk to Crystal Palace very early in the morning (see also 27 Queen Anne Street). The Palace was still closed to visitors, but, as he relates:

The guard which watches over the gates of this Louvre were used to seeing me at all sorts of strange hours, and so let me walk in. The deserted inside of the Exhibition palace at seven in the morning was a spectacle of original grandeur: the vast solitude, the silence, the gentle light coming from the transparent roof, the dried-up fountains, the silent organs, the motionless trees, this harmonious display of opulent goods brought from the four corners of the world by rival peoples. These ingenious creations, the products of peace; the engines of destruction that brought war to mind; all the causes of movement and noise – while human beings were absent, everything seemed to be holding a mysterious conversation together in the strange language that can be heard with the ear of the mind. […]

At some point during his contemplation and walk around the hall, Berlioz suddenly heard a sound:

a noise rather like that of rainfall spread under the vast galleries; it was the waterfalls and fountains which the wardens had just turned on. The crystal castles, the artificial rocks, all quivered under the flow of their liquid pearls; the policemen, these worthy guards without arms, were going to their stations...

The palace was getting ready to receive the visitors of the day:

The silence had kept me awake, but these sounds made me feel drowsy; the need for sleep had become irresistible; I came to sit before Erard’s large piano, that musical marvel of the Exhibition. I leaned on the ornate lid, and I was about to fall asleep when Thalberg touched me on the shoulder, saying: ‘The jury is assembling, colleague! Take heart – today we have thirty two musical snuffboxes, twenty four accordions, and thirteen bombardons to examine’.

On his return to Paris he was invited to attend the week-long Paris Fête, or what Berlioz referred to in one of his letters as ‘les fêtes anglo-parisiennes’ (CG no. 1427). The event started on 1st August; the Executive Committee of the Exhibition, the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London, had all been invited by Louis Napoleon and the city of Paris. According to John Davis, it included ‘a banquet at the Hôtel de Ville, a reception hosted by Napoleon at St Cloud, a fête at the British Embassy, a review at the Champs de Mars, and a performance at the Théâtre Français, including a ballet entitled Crystal Palace’ (The Great Exhibition [Stroud, 1999] pp. 168-169).

While Berlioz was in London he had toyed with the idea of staging a Musical Festival at Crystal Palace, where he would conduct various works including his own Te Deum, written in 1848-9 but not yet performed, but his plans did not materialise (CG no. 1418).

During his 1855 visit Berlioz went to a concert held at the Crystal Palace. A letter of his refers to this visit (CG no. 1984), and extant is also a letter by Marie Recio, Berlioz’s second wife, to her friend Mme Duchène relating the same experience (quoted by Ganz [1950], p. 202; the original French text is in CG vol. V, p. 123 n. 1). By that time Crystal Palace had been ‘moved’ to Sydenham (see below), and a large concert hall had been erected in the central transept of the building. This hall held so many people that only a small charge was made for admission. In October 1855 Berlioz discussed the possibility of doing himself a large concert there, but the plan failed to take shape (CG no. 2036).

As a measure of Berlioz’s fame in London, it is interesting to note that in 1851 one of his correspondents (his name is not known) had sent him a letter with the envelope addressed ‘To Monsieur Berlioz in London’, and the letter reached its destination! In his letter of 11 June 1851 Berlioz writes to this friend (CG no. 1418):

[…] I am answering you by return post; don’t accuse me of negligence; your letter had only the words: ‘To M. Berlioz in London’ written on, and so it went round in circles before reaching me, hence my delay in replying. […]

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, all the pictures on this page have been scanned from engravings, medals, postcards, prints, objects and books in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

The above 1851 engraving is by George Baxter.

The above engraving was published in Cassell’s Illustrated History of England, by John Frederick Smith, William Howitt and John Cassell, volume IV, 1862 (p. 121); it is in our collection.

This engraving dates from the 19th century.

This steel engraving dates from the 19th century.

This 1951 print is a reproduction of an original 1851 engraving of the Great Exhibition.

This image shows the lid from a contemporary pot of meat-paste, representing the Crystal Palace. The original is in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK.

The original copy of this engraving is in the Guildhall Library, City of London / The Bridgeman Art Library.

This engraving of the entrance to the main hall has been reproduced courtesy of Dr John Davis from page x of his book The Great Exhibition.

A copy of this engraving is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The original copy of this engraving is in the BBC Hulton Picture Library.

The original copy of this engraving is in the BBC Hulton Picture Library.

![]()

This picture was published in L’Illustration on 10 May 1851, a copy of which is in our collection.

The above 1851 engraving is H. Bibby.

This picture was published in L’Illustration on 10 May 1851, a copy of which is in our collection.

![]()

Crystal Palace was re-erected in Sydenham in 1854. The Triennial Handel Festivals were held here between 1859 and 1926, with chorus and orchestra of up to 4000 performers (see below). Other events such as Saturday concerts conducted by August Mann (between 1855 and 1901), Schools Choral Festivals and the like were also held at the Sydenham site. Originally owned by a private company, the Crystal Palace became national property by public subscription in 1913; it was destroyed by fire in 1936 (Elkin, 1955).

![]()

This engraving, showing the Handel Festival, was published in the Illustrated London News in 1859.

This photo shows a great “Festival Concert”, possibly one of the ‘Handel Triennial Festivals’, given in the concert hall under the direction of Frederic Hymen Cowen; it was published in Musica (vol. III, 1905; Publications Pierre Lafitte, Paris).

We are most grateful to our friend Gene Halaburt for sending us this picture.

![]()

|

Front

|

|

|

Front

|

Back

|

|

Front

|

Back

|

Front

|

Back

|

|

Front

|

Back

|

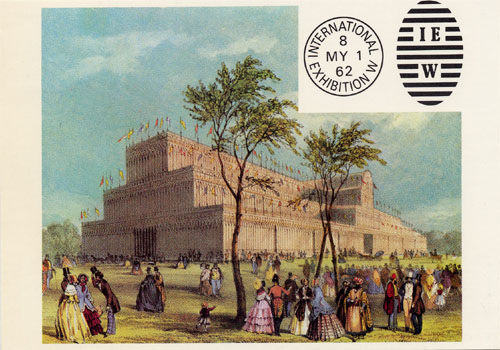

This card reproduces a contemporary engraving of the 1851 Exhibition. The inset shows the postmark used at the 1862 Exhibition. It was issued to commemorate the National Postal Museum Exhibition, ‘Exhibitions in London 1851-1951’ which was held from 6 January to 1 July 1983.

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.