![]()

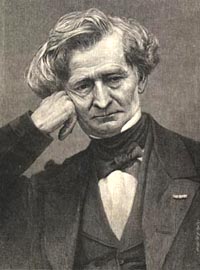

HECTOR BERLIOZ.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES AND PERSONAL REMINISCENCES.

BY THE COMPOSER OF “SALAMMBÔ.”

Published in the Century Monthly Magazine,

December 1893![]()

|

HECTOR BERLIOZ.BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES AND PERSONAL REMINISCENCES.BY THE COMPOSER OF “SALAMMBÔ.” Published in the Century Monthly Magazine,

December 1893

|

|

ROBABLY no musician has ever been

more ridiculously criticized, more scoffed at, more insulted, than was Berlioz

during the greater part of his career. And these outrages were heaped upon him

by his own country! He was only too sensible of this fact. Luckily he possessed

beak and claws, as certain feuilletons in the “Journal des Débats” attest.

ROBABLY no musician has ever been

more ridiculously criticized, more scoffed at, more insulted, than was Berlioz

during the greater part of his career. And these outrages were heaped upon him

by his own country! He was only too sensible of this fact. Luckily he possessed

beak and claws, as certain feuilletons in the “Journal des Débats” attest.

After age, disease, and discouragement had rendered him less eager for the fray, he was allowed a little more peace; but when the “Trojans” appeared, those of his maligners who still survived availed themselves of the occasion to renew the attack. Among these the critic of the “Revue des Deux Mondes”, the unimpeachable Scudo, who died stark mad a short time afterward, was one of the first to make himself prominent by the violence of his attacks and the extravagance of his pen, which, by the way, did not fail to recoil somewhat upon him. The day after the first performance of the symphony of “Harold”, Berlioz received an anonymous letter in which, after a tirade of coarse abuse, he was charged with being “too cowardly to blow out his brains”. Scudo never ventured to go so far as that, — not that he was lacking in the will, — but one day he wrote this sentence, which is worthy of being recorded: “The Chinese, who amuse their leisure moments by the sound of the tom-tom; the savage, who is roused into fury by the rubbing together of two stones, make music of the kind composed by M. Hector Berlioz”. The insult, with the signature of its author, should go down to posterity beside the name of the illustrious artist whom it wounded. It is worthy to be written under the list of his masterpieces on the pedestal of the statue erected to him by the tardy enthusiasm of his fellow-citizens.

The reaction preceding his apotheosis was not slow to appear. It began almost immediately after the death, in 1869, of the man who, perceiving as in a sudden flash of light the glory that awaited him, said with his last sigh: “On va donc jouer ma musique!” I was there, at his bedside, gazing upon that pale, noble head, with its magnificent crown of white hair, waiting in anxious affliction for the last breath to be exhaled from those thin and colorless lips.

I watched over him all night. In the morning his faithful servant handed me the copy of his memoirs designed for me. I had occasion at a later period to reward this honest man, who, during the long sickness of Berlioz, had not left him for a single moment, lavishing on him the most devoted care. A short time before the death of his master, he had accompanied Berlioz to my house. Painfully did the poor musician mount up the four flights of stairs to come and sit at my table. After the meal I begged him to write his name on the score of “Benvenuto Cellini”. He seized a pen, wrote with a trembling hand “A mon ami”, and then, looking at me with a wistful glance, said: “I have forgotten your name”. It was a cruel blow, which went to my very heart. I was to see him no more till I gazed on his face as he lay upon his death-bed, that master whom I had so much admired, and on whom I had bestowed an affection which he could never doubt from the very moment when I first had the happiness to make his acquaintance. M. Adolphe Jullien, to whom I related this sad incident, has recorded it in his beautiful book entitled “Hector Berlioz: his Life and Works”, the most complete monument which has ever been reared to the memory of the immortal author of the “Trojans” and the “Damnation of Faust”.

I had not long been acquainted with Berlioz when his “L’Enfance du Christ” was performed for the first time, under his direction, in the Salle Herz, in the month of December, 1854. I was seated beside one of his intimate friends, Toussaint Benet, the father of the pianist Théodore Ritter, then almost a child. The emotion which I felt was such that at the end of the second part I burst into tears, and was on the point of fainting. My neighbor pressed my hands in his to restrain me from uttering a cry. From that time my admiration for Berlioz knew no bounds, and I began to study his works, with which I had had but slight acquaintance, never having had an opportunity to hear them. The Parisians were not at all pleased with them. The success of “L’Enfance du Christ” was, however, very great, and this piece opened to Berlioz the doors of the French Academy, of which he became a member two years afterward. Clapisson entered first. The very day of the election of the author of “La Promise”, who was not yet the author of “La Fanchonnette”, I was walking on the boulevard with the author of “L’Enfance du Christ” and certain earlier masterpieces. It was the moment when the balloting was going on under the cupola of the Mazarin palace, and he was impatient to know the result. “But why?” I said to him. “At this very moment Clapisson is being elected”. “You are a bird of ill omen”, replied he, jumping into a cab to go to the secretary of the Academy, hoping to get a little earlier account of — the triumph of his competitor. I was not mistaken.

Toussaint Benet, whose name I have mentioned above, was a jovial fellow from Marseilles, who, possessed of an ample fortune, had settled at Paris to educate his son in music. Berlioz had recognized in the young Théodore a remarkable precocity and exceptional talents, and had taken great interest in him. He gave him the scores of the masters to read, and pointed out their beauties. Berlioz and I often met at the rooms of Toussaint Benet. The child had grown up, and on his return from Germany, where he had been to take lessons from Liszt and the learned Professor Schnyder von Wartensee, he was already something more than a surprising virtuoso; he was even a finished musician. What delightful evenings I owe to him! After dinner young Ritter would sit down at the piano and play his favorite works, “Romeo and Juliet” and the “Damnation of Faust”, in turn. This was long before the appearance of the “Trojans”. Berlioz, seated before the fire with his back toward us and his head bowed, would listen. From time to time a sigh would escape him: a sigh — perhaps a sob. One evening, I remember, after the sublime adagio of the “scène d’amour”, he suddenly rose, and, throwing himself into the arms of Théodore, exclaimed in an ecstasy, “Ah, that is finer than the orchestra!” No, it was not finer; but it gave the impression, produced the illusion, of orchestra, so exquisite were the nuances in the playing of this most skilful virtuoso, so various were the qualities of tone — now delicate and caressing, now bold and passionate — that he evoked from his instrument. Nobody has ever equaled Ritter in this peculiar talent of making a piano suggest an orchestra.

No stranger, no friend even, — if we except a young relative of the family, — assisted at these reunions. Berlioz and I would withdraw together; he would accompany me to my house, I would see him to his, and we would walk the distance over two or three times, he smoking ever so many cigars, which he never finished, sitting down on the deserted sidewalks, giving himself up to the exuberance of his spirits, and I laughing immoderately at his jokes and puns. Ah, how few have seen him thus! The moment came to separate. Usually I accompanied him to his door, covetous of the last word. As we approached his house in the Rue Calais (to-day it bears a commemorative tablet, tardily set up), his enthusiasm vanished; his face, lighted up by the flickering gas-jet, settled into its habitually sad, careworn expression. He hesitated a moment as his hand touched the bell-pull, then murmured a cold, chilly adieu in a suppressed voice, as if I were never to see him again. He entered his house; and I — I went away with my heart torn, knowing well what a painful reaction would succeed the few hours of unbending delight and childish glee I had just witnessed.

Seven months after the death of his first wife Berlioz married again (in October, 1854). “This marriage”, he wrote to his son, “took place quietly, without any parade, but also without any mystery. If you write me on this subject, do not mention anything that I cannot show my wife, because I am very anxious that no shadows should settle on my home”. In a letter addressed to Adolphe Samuel some years after he says: “I am sick, as usual; besides, my mind is restless and disturbed, ... my life seeks consolation abroad; my home wearies me, irritates me, is an impossible home, quite the contrary of yours. There is not a day or an hour when I am not on the point of ending my life. I repeat, I am living in thought and in affection far away from my home; ... but I can tell you no more”. Had he not said enough in this to make himself understood? After the death of his second wife, June 14,1862, Berlioz continued to live with his mother-in-law, who cared for him with unfailing tenderness. This worthy woman was the widow of Major Martin, who had been in the Russian campaign with Napoleon. In company with her husband she had braved the cold, the snow, and all the other dangers of the journey with a babe in her arms. She was a courageous woman, who concealed great sensitiveness of feeling beneath a mask of impassibility. She idolized the genius of Berlioz, and every enemy of the great artist became her own. Her grateful son-in-law left her at his death the use of all he possessed, with the exception of some private bequests and his manuscripts, which went to the Conservatory. I see her still, trembling with emotion, but rigid as a specter, as she sat far back in her opera-box, the evening, a year after the death of the master, when we held the festival which was the first shining of the posthumous glory with which posterity should avenge him. Our finest artists sought the honor of appearing on that program, where the great names of Gluck, of Beethoven, and of Spontini were associated with that of Berlioz, the only contemporary musician who had nothing to fear from such dangerous companionship. Unhappily, the pecuniary result of this noble occasion came very far from answering the expectations of the friends and disciples who organized it. Many years were still to elapse before these disciples should record in bronze his complete glorification and final apotheosis.

The unveiling of the Berlioz statue took place on the 17th

of October, 1886. The sky was leaden, the weather cold and rainy, but the

approaches to Montholon![]() Square had been invaded from an early hour in the

morning. When the veil fell which covered the statue, and the first tone of the

triumphal symphony swelled out, what an immense acclamation and long cry of

enthusiasm burst among the multitude! This brilliant homage bestowed “on

one of the most illustrious composers of any age, the most extraordinary one,

perhaps, that ever existed”, had long been in preparation by the directors

of our three great musical societies, Messrs. Pasdeloup, Colonne, and Lamoureux.

By initiating the public little by little into the beauties of the master’s

wonderful conceptions, they had conducted with ever-increasing success the work

of reparation and of public recognition which had been started at the Opéra,

and some years later was renewed at the Hippodrome.

Square had been invaded from an early hour in the

morning. When the veil fell which covered the statue, and the first tone of the

triumphal symphony swelled out, what an immense acclamation and long cry of

enthusiasm burst among the multitude! This brilliant homage bestowed “on

one of the most illustrious composers of any age, the most extraordinary one,

perhaps, that ever existed”, had long been in preparation by the directors

of our three great musical societies, Messrs. Pasdeloup, Colonne, and Lamoureux.

By initiating the public little by little into the beauties of the master’s

wonderful conceptions, they had conducted with ever-increasing success the work

of reparation and of public recognition which had been started at the Opéra,

and some years later was renewed at the Hippodrome.

One after another the detractors of Berlioz are disappearing. To-day only few remain. These timidly hazard a criticism or two in the following style: “Doubtless he is a great poet in music, but he imagines at times an ideal that neither his pen nor his genius is capable of realizing. ... He does not always write with that firmness of hand which is the prime quality of a perfect musician. ... His style exhibits defects resembling hesitation, and then there are awkward passages which often mar his work”. Heaven pardon me! I think some, in memory of Cherubini, reproach him also with not knowing how to make a fugue — a man who has written fugues both vocal and instrumental, so perfect, so melodic, in his dramatic symphonies of “Romeo and Juliet”, the “Damnation of Faust”, in his sacred trilogy of “L’Enfance du Christ”, in the “Mass of the Dead”, in almost every one of his great works!

Such was the opinion of that composer, always mediocre, and to-day discredited and forgotten, to whom I used to vaunt the beauties of Berlioz’s symphonies. Refusing to admire or to comprehend them, he would close the discussion with this phrase, astounding in its folly and stupidity: “What would you have? Berlioz and I do not speak the same language!”

But do not all innovators, all artists of genius, bear the same reproach? Was not Titian charged with not always being correct in his sketches; Delacroix, with not knowing his business; Spontini, with knowing less than the poorest pupils in the Conservatory, who laughed at him? And did not Handel say of Gluck, the author of “Alceste” and of “Armide”, “He is as much of a musician as my cook”?

Poor Berlioz! He heard things to make him wince after he wrote his “Trojans at Carthage”. True, at this period of his life invective was not used against him with such violence as in the earlier contests, but the most unjust and bitter criticisms were not wanting. I have cited a few of the “amenities” that Scudo indulged in every time he had occasion to mention a composition of Berlioz. I add another emanating from a pen less authoritative than that of the critic of the “Revue des Deux Mondes”, but a pen wielded by a man who commanded a much larger number of readers through his position on one of the most widely circulated journals of Paris.

Having characterized the score of the “Trojans” as “a mountain of impotence compared with the chefs-d’œuvre that shine in the heaven of music”, he gave M. Carvalho a piece of good advice: “Why not replace the specters of Priam, Chorèbe, Cassandra, and Hector, too little known to the public, by four others which should address Berlioz in the following words? The first: ‘I am Gluck; you admired me, you spoke of my “Alceste” in rare terms of eloquence, and to-day you dishonor my recitative, so strong in its sobriety, so grand in its simplicity.’ The second: ‘I am Spontini; you loved my “Vestale” more than Licinius did; you say you are my disciple, and you extinguish its burning rhythm with the stagnant waters of your sluggish melopoeias. Lay aside those fillets which I have bequeathed to my fellow-countryman Rossini.’ The third: ‘I am Beethoven, author of so many immortal symphonies, rudely torn from those visions which attend the illustrious dead, as they lie on the couch of their glory, by your symphony “La Chasse Royale”.’ And the fourth: ‘I am Carl Maria von Weber. After having learned instrumental coloring from my school, you rob me of my palette and my brushes to daub on images worthy of a village painter’.”

Further on, speaking of “La Chasse Royale”, the same critic, whose resources are inexhaustible, adds a few reflections to the monologue of Beethoven: “If the violent and horrible dissonances maintained through the strains of the orchestra are music; if that charivari which surpasses the pitiful and presumptuous failure of Jean Jacques at the Geneva1 concert (!) be art, I am a barbarian. I am proud of it. I boast of it”. There is some truth in this.

The first representation of the “Trojans” took place at the Théâtre Lyrique, November 4, 1863. Berlioz, as he relates in his memoirs, had composed this work at the instance of the Princess of Sayn-Wittgenstein, to whom he dedicated it. The princess lived at Weimar, where Liszt was director of the grand duke’s chapel. She requested the grand duke to write to the Emperor Napoleon III. to request that rather unmusical sovereign to have the “Trojans” brought out at the Opéra. The Opéra was directed at that time by Alphonse Royer, one of the authors of the libretto of “La Favorite”, a charming man, possessed of exceedingly distinguished manners. Berlioz went to several receptions at the Tuileries, and came away as he had gone. But one evening the emperor, perceiving him, asked him about the “Trojans”, and expressed a desire to read the poem. Great was the joy of the composer, who thought the game was won. It was not long, however, before he was undeceived. The poem, sent back through the director of theaters by the emperor, who certainly had not read it, was thought to be “absurd and stupid”, and of a length that far exceeded the ordinary dimensions of a great opera. A year afterward, Alphonse Royer told Berlioz, who could not believe his senses, that the “Trojans” was going to be “studied”, and that the minister of state, “desirous of giving him full satisfaction”, commissioned him to report this happy news. Nothing more came of the matter. “Tannhäuser” was represented instead of the “Trojans”, and by an imperial order. The exasperation of Berlioz knew no bounds. Then it was that he accepted the proposition of M. Carvalho, who agreed to put on the stage the second part of the work, the “Trojans at Carthage”, reserving the “Fall of Troy” for a second trial, in case the first should succeed. After a series of twenty performances, sustained with difficulty, the “Trojans” disappeared from the bulletin-board, and has never since graced it. I was at Weimar a short time after the first representation. It was the birthday fête of the grand duchess. I was invited to court and presented to the grand duke, who immediately inquired about Berlioz, of whom he was personally very fond, and whose works he passionately admired. He told me that he had been delighted to hear of the success of the “Trojans” at the Opéra. “But, sir”, I rejoined rather hastily, “the ‘Trojans’ was not played at the Opéra, but at the Théâtre Lyrique”. “Why, I wrote an autograph letter to the emperor, and I thought —” I might have finished his phrase. The emperor had undoubtedly received the letter, but had paid no attention whatever to it.

When I came back to Paris I related to Berlioz my conversation with the grand duke. “How!” cried he, with astonishment. “You told him! You undeceived him! Ah, I never would have dared to do that”. The error was easy of explanation: the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar had been informed that the “Trojans” had just been played at Paris, and he had made no further inquiry. A little more, and he would have written a second letter to the emperor — to thank him!

Berlioz never heard the “Fall of Troy”, except a single fragment, — the duo between Chorèbe and Cassandra, — sung by the barytone Lefort and Madame Pauline Viardot, at one of the concerts directed by the master at Baden in the merry season — that season in which “Tout Paris” came together in the coquettish little town of the grand duchy. This first part of the “Trojans”, superior to the second in the judgment of many musicians, has not to this day been performed at Paris, except at concerts. M. Pasdeloup first gave one act, then two; and lastly the whole work, on the same day on which it was given by M. Colonne at the Châtelet (December 7, 1879). The star of the founder of popular concerts2 had begun to wane, and, besides, the execution was better, and much more careful, at the Châtelet than at the Cirque d’Hiver. M. Colonne, however, was able to give only four representations of the “Fall of Troy”, while the success of the “Damnation of Faust”, after more than fifty performances, is far from being exhausted.

Madame Rose Caron was the young artist who sang at Pasdeloup’s the little part of Hecuba in the fine ottetto of the second act. She hardly suspected at that time that she would become a few years later the great lyric tragédienne so applauded by Paris, for whom no rival need be sought, because there is none.

The “Trojans” complete, but played in two successive evenings,3 has lately obtained an immense success at Carlsruhe. The Capellmeister, Felix Mottl, a spirited Wagnerian, was the one who took the initiative in this grand manifestation. Unfortunately, it will doubtless produce a greater stir in Germany than with us of France.

It is ever to be regretted that the attempt of M. Lamoureux to produce “Lohengrin” at the Eden Théâtre failed on account of the threats and hisses of a troop of rattle-brained blackguards. The success of “Lohengrin” would have paved the way for that of the “Trojans” and “Benvenuto Cellini”; and, sanctioned by the theater, as it already had been by the concert, the fame of Berlioz would have been much more complete and glorious. Berlioz and Wagner applauded in turn upon the same stage, and that, a French one! Why not? The hostility existing between those two musical geniuses, the hatred with which the latter pursued the former, has but little interest at the present day except for biographers; the musical world cares little for it. Nobody denies to the one the priority of certain innovations, certain harmonic and instrumental combinations by which the other may have profited; but to try to make out the inventor of the modern lyric drama to be the humble imitator of his predecessor, who was above all a great innovator as a symphonist; to brand as plagiarisms a few involuntary reminiscences, a few chance coincidences, such as few composers, even those most original and most distinguished, have been able wholly to avoid, marks the difference between a rational and just opinion and an imbecility.

The first concert given by Richard Wagner at the Théâtre Italien, on the 25th of January, 1860, had just come to an end. Madame Berlioz, passing by leaning on the arm of her husband, said to me in her sarcastic tone, “Oh, Reyer, what a triumph for Hector!” And why? Because a certain air of kinship seemed to be discoverable between this or that passage in the prelude to the third act of “Tristan and Isolde” and the fugued theme of the “Convoi de Juliette”; between the figure played by the violins in the Pilgrim chorus in “Tannhäuser”, and that which accompanies the oath of reconciliation between the Montagues and the Capulets over the inanimate bodies of Juliet and Romeo; because the ascending progression in the admirable prelude of the third act in “Lohengrin” was drafted, it is said, on that which ends at the principal motif of the “Festival at Capulet’s” in the symphony of “Romeo”. And the flatterers, happy to be able to point out those supposed coincidences to Berlioz, who perhaps had already perceived them, did not fail to exaggerate them. No, no; Hector would not have triumphed for so small a thing. And when, the day after the third concert, given with the same program as the two preceding ones, there appeared in the feuilleton of the “Débats” that famous credo which marks with an ineffaceable line the break between Berlioz and Richard Wagner, the most fervent admirers of Berlioz, instead of reciting devoutly the “act of faith” which spite or anger had dictated, did much better by beginning to study the works of Wagner, and trying to penetrate their undoubted beauties. There was certainly more profit for them in that course, and I affirm that some of them have not come out the worse for it.

During their stay in London Berlioz and Richard Wagner maintained friendly relations. Later, a German newspaper is said to have published an article, written by no less a personage than Wagner himself, in which Berlioz was very roughly handled. Some one, doubtless a friend of one of the parties, translated it so that Berlioz could read it with more ease, and sent it to him. The latter, it may be conceived, exhibited no little irritation. The story is probable enough; I will not be responsible for its truth.

Berlioz had a son named Louis, of whom he was very fond. In 1867, having been recently appointed captain in the merchant service, the young man suddenly died at Havana, in his thirty-fourth year. Berlioz learned this sad news just as he was getting ready to pass an evening at the house of one of my friends, the Marquis Arconati-Visconti. Arconati had organized in honor of the master he admired — for he had not failed to be present at a single performance of the “Trojans” — a private entertainment, to which several artists, and among others Théodore Ritter, had been invited. Berlioz did not come. Ritter repaired to his house, and found him in tears. The great composer outlived that son who was his only consolation and pride scarcely two years. Louis Berlioz, however, was not a musician, either by temperament or by instinct; and there is no doubt that on the rare occasions presented to him of hearing his father’s music, his filial piety alone induced him to admire it.

Berlioz left me by his will a volume of “Paul and Virginia” with his name written in it, and with his autograph notes. One of these annotations (most of them are very curious) has been reproduced in the very remarkable and interesting work by M. Adolphe Guken. Here it is: “To sum up, a book sublime, heartrending, delicious, but which would make a man an atheist if he were not one already”. It is found quite at the end of the romance, and is followed by certain chords which reproduce in the minor mode those which are found on the first page of the book. I have never believed in the atheism of the man who wrote the poem and the music of “L’Enfance du Christ”, who sang such pure melodies to the Virgin Mary and to the angels guarding the sleep of the Child Jesus. A free-thinker — like his father, Dr. Berlioz — he was, perhaps; but nothing more. When the hearse which bore the remains of the master arrived before the Church of the Trinity, the horses reared and refused to advance. This was very much noticed and commented on at the time, with reference to the anti-religious sentiments of the illustrious dead. I imagine, however, that like accidents may have occurred more than once at the burial of very fervent Catholics.

A few days after the concert which I directed at the Opéra, March 22, 1870, Madame Damcke, the testamentary executrix of Berlioz, was kind enough to present me with an orchestra score of the “Messe des Morts”, annotated and corrected by the author. I have also in my library a copy, given me by Berlioz himself, of the symphony “Romeo and Juliet”, with his autograph corrections and some changes introduced into the instrumentation of the first morceau in fugue style, principally in the altos and violoncellos. This score bears the date of 1857, and the symphony is dated September, 1839. Eighteen years after its publication, Berlioz discovered faults in the engraving, and whole passages to modify.

The day after my election to the Institute, I saw coming to my house the faithful servant whom I mentioned at the beginning of this article, the same who had nursed Berlioz with such devotion during his long sickness, and whom for many years I had not seen. He brought me the Academician’s coat and sword, which his master had intrusted to him to be delivered to me — when the moment should come. I had been elected the night before; he had lost no time. He related to me how during the war his house, situated in the outskirts of Paris, had been pillaged by the German soldiers. Nevertheless, he had succeeded in concealing these relics from the rapacity of Prussians and Bavarians. I preserve them with religious veneration; and, as I have no great love for uniform, make as little use of them as possible. I ought, perhaps, to have exhibited them to the inhabitants of La Côte Saint-André when I went there last September to attend the inauguration of the Berlioz statue in the little town where he was born. This statue is a reproduction of the one in Montholon Square; it was unveiled with great pomp, the minister of public instruction and fine arts presiding at the ceremony, with all the authorities of the town and the department gathered on a vast platform, and a large number of Orpheonic societies drawn up around the pedestal. Medals with the bust of the master were sold in the street; flags waved at the windows of the houses; and upon the front of the one in which Berlioz was born you could read engraved upon a marble slab that inscription which ought to have been placed there twenty years before:

“To HECTOR BERLIOZ,

FROM HIS FELLOW-CITIZENS, HAPPY IN HIS

GLORY, AND PROUD OF HIS GENIUS”.

But for the commemorative slab no particular mark would point the attention of tourists to that house, so plain in its appearance and so simple in its architecture. It belongs today to a grocer.

I said that I have no great faith in the atheism of Berlioz; neither do I believe much in his Platonism. Nevertheless, he has devoted some twenty pages in his “Memoirs” to the story of his passion for Mme. F—, with letters to prove it, and some details which have always seemed to me rather puerile. Like Dante, he was ambitious of having a Beatrice — a very beautiful Beatrice apparently, but rather rustic, whom he knew very little, having seen her only three or four times at most, and those at long intervals. She was older than he, and was some seventy years of age when, having gone to visit her at Lyons, he came near fainting at her feet. It was at Meylan, a little village of the Dauphiné which overlooked the valley of the Isère, that she appeared to him one fine day wearing little pink shoes. She was then eighteen; he was twelve. That vision was never erased from his memory. “No; time can have no effect... new loves never erase the first one”. Her name was Estelle, but to him she was always the nymph, the hamadryad of St. Eynard, the stella montis. That name was the one he wrote in the last line of his “Memoirs”: it was perhaps that name, too, that he murmured when he heaved his last sigh.

Ernest Reyer.

_____________________

1

“The Confessions” have taught those who have

read them that that wretched “Geneva” concert took place at Lausanne!![]()

3

It must be conceded that Berlioz made a mistake in

fixing four hours and twenty-six minutes as the time required for the

representation of this work; and about three hours and three quarters with the

suppressions which he himself indicated in the complete score just issued by the

publishers Choudens.![]()

![]()

* This article has been scanned from a copy of the December 1893

issue of the Century Monthly Magazine, in our own collection. The

original spelling, syntax and punctuation of the article have been preserved

(for example, the name of Toussaint Bennet is given as Toussaint Benet).

Berlioz’s engraved portrait, reproduced here on the top-left corner, accompanies

the original article on a separate page.

The same article was republished in The International Library of Music,

1925 (New York: The University Society), a copy of which is also in our

collection. The original French version of the article dates from 1891.![]()

** Reyer’s memory is

betraying him: in fact the square is the Square Berlioz in another part of the

9th arrondissement.![]()

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created in March 2005.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains

Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil