Berlioz and Exeter Hall

1852

1853

1855

Exeter Hall and its history

Exeter Hall in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz first conducted concerts in Exeter Hall in 1852, and he conducted again there in 1855. But soon after his arrival in London in 1847 he had started to attend concerts there – on 17 November 1847 he heard for the first time Mendelssohn’s Elijah (Correspondance Générale no. 1144, hereafter CG; Les Soirées de l’Orchestre, 21st Evening, from Journal des Débats, 31 May 1851) and on 13 March of the following year he also heard for the first time his Italian Symphony (CG no. 1187). On 7 April 1852 he seems to have attended a performance of Handel’s Messiah (CG no. 1469bis, though the dating is uncertain); but whereas Berlioz was at one with English musical taste in his admiration for Mendelssohn, he remained temperamentally opposed to Handel (cf. e.g. CG nos. 1545, 1987, 1991, 2203, 2317).

![]()

The series of six concerts given by Berlioz in Exeter Hall in 1852 was one of the most important he gave in his whole career. The programmes of the concerts were as follows:

First concert (24 March): (Part I) Mozart, Jupiter Symphony (no. 41); aria of Thoas (sung by bass voices from the choir) and ballet from Iphigenia in Tauris by Gluck; Beethoven, Triple Concerto (Silas, piano; Sivori, violin; Piatti, cello); Weber, Overture Oberon (Part II) Berlioz, Romeo and Juliet, first four movements; Bottesini, Fantasia for double-bass played by himself; Rossini, Overture William Tell

Second concert (14 April): (Part I) Cherubini, Overture Anacreon; aria from Iphigenia in Tauris by Gluck (sung by Alexander Reichardt); Bortniansky, Chant des Chérubins (arr. by Berlioz); Henry Wylde, Piano concerto (Alexandre Billet, piano); F. Gambert, Liebeslied (sung by Alexander Reichardt); Beethoven, 5th Symphony (Part II) Mozart, Overture The Magic Flute; Edward Loder, Cantata The Island of Calypso

Third concert (28 April): (Part I) Mendelssohn, Overture Fingal’s Cave; Berlioz, Romeo and Juliet, first part; chorus and aria from Gluck’s Armide; Weber, Konzertstück for piano and orchestra (Mme Pleyel [née Camille Moke], piano) (Part II) Weber, Overture Euryanthe; Spontini, La Vestale Act II; Beethoven, overture Egmont

Fourth concert (12 May): (Part I) Beethoven, Choral Symphony (no. 9) [conducted by Berlioz] (Part II) [conducted by Henry Wylde] Mendelssohn, Piano concerto in G minor (Mlle Clauss, piano); vocal pieces by Wylde and Handel; Weber, Overture Der Freischütz; Mendelssohn, Wedding March

Fifth concert (28 May): (Part I) Mendelssohn, Italian Symphony (no. 4); Mercadante, Romanza; Silas, Piano concerto in D minor (Silas, piano); vocal piece by Henry Smart; Berlioz, Overture Les Francs-Juges (Part II) Mendelssohn, Violin concerto (Sivori, violin); Beethoven, Overture Leonora no. 2; aria by Handel; Weber, Invitation to the Dance (orchestrated by Berlioz)

Sixth concert (9 June): (Part I) Beethoven, Choral Symphony (Part II) Wylde, excerpts from a cantata; Berlioz, excerpts from the first two parts of the Damnation of Faust, including the Hungarian March and Dance of the Sylphs; Liszt, transcription of the Skaters’ Waltz from Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète and Tarantella from Rossini’s Soirées musicales (Mme Pleyel, piano); Benedict, chorus; Weber, Overture Jubilee

Berlioz’s correspondence gives detailed reports on most of these concerts, except for the second and the fifth (see also the Memories of a Musician (1913) by Wilhelm Ganz, who played in the orchestra and confirms what Berlioz says in his letters). The day after the first concert Berlioz wrote to his friend Joseph d’Ortigue (CG no. 1461):

I am writing to you a few lines to let you known that I scored a colossal success. I don’t know how often I was called back, and I was acclaimed both as composer and as conductor. This morning I read in the Times, the Morning Post, the Morning Herald, the Advertiser and others, eulogies such as have never been written about me. […]

There is dismay in the camp of the old Philharmonic Society; Costa and Anderson are drinking their bile by the full glass. […]

Be reassured, all is well. I have a great orchestra and a wonderful impresario (Beale) who does not count pennies. Since yesterday he is half mad with joy.

This success is a great event for the art of music in London and for me personally. From what everyone says there can be no doubt about the consequences. […]

A few days later he wrote to Liszt (CG no. 1462, 29 March):

[…] I have just had a huge success at Exeter Hall, at the very moment when you were conducting in Weimar the second performance of Benvenuto. The New Philharmonic Society has a vast and magnificent orchestra: 20 first violins, 18 seconds, etc... and all this works like a good quartet. […]

Concerning the second concert the only detailed information provided by the correspondence is an open letter of Berlioz to the composer Edward Loder in Manchester apologising for shortcomings in the performance of his cantata The Island of Calypso; the letter was published (in English translation) in the journal The Musical World, but the original French text has not survived (CG no. 1472, 15 April).

The third concert is much more fully documented. A letter of 20 April to Pierre Érard the instrument maker, who was settled in London at the time and whose sister had married Spontini, tells of the rehearsals for excerpts from La Vestale, a work that had great significance for Berlioz (CG no. 1473; Spontini had died the previous year):

I have just come from the first rehearsal of the excerpt of La Vestale which we are performing at our third concert at Exeter Hall, next Wednesday 28 April, at 8 o’clock.

The musicians are in a state of surprise and admiration which is hard to describe. And they had come with the hostile prejudices which a sort of anti-Spontini faction had been deliberately spreading in London for the last twenty five years. I believe I am going to teach them a hard lesson. The impact will be huge; we have 120 choristers and a huge orchestra. Staudigl sings the High Priest and Mme Novello Julia; for Licinius I have a young German tenor, Reichardt, whom I am coaching in the part, and he should do.

Try to come with Mme Spontini to witness a triumph that matters twenty times more than those achieved on the continent. To see the crushing of a cabal that has been going for a quarter of a century! That is a joy that is not to be experienced often. You must come at all costs.

The same day Berlioz invited Mme Spontini to come from Paris (CG no. 1474bis [in vol. VIII]). A week later she wrote to Berlioz announcing her arrival (CG no. 1476, 28 April):

[…] Allow me to offer you the conductor’s baton which my dear husband used for conducting works by Gluck and Mozart as well as his own. It could not be better placed than in your capable hands. This evening, when conducting La Vestale, it will remind you even more keenly of our dear Spontini who was so fond of you and had such admiration for your works!… […]

In the event, though the concert was a success, the result was not altogether what Berlioz had hoped, as he writes to d’Ortigue on 30 April (CG no. 1477; cf. 1478):

[…] Our third concert took place the day before yesterday in the evening, and included the second performances of the first four parts of Romeo and Juliet. Everything was played with a verve, finesse and intelligence that are unknown in this country. There were moments when the orchestra exceeded in power everything I have heard so far. The movement of the Festivities, which had not fully satisfied me the first time, was played as nowhere before… and would you believe that in the Introduction the trombone solo was interrupted after its third period by a round of applause?

As for the cheers that greeted the rest, I wish you had been there to hear them. The newspapers continue to support me warmly (with the exception of the Daily News, which is edited by M. Hogarth, a worthy old gentleman who up till now had been on very friendly terms with me, but who for a number of years has held the position of secretary of the old Philharmonic Society. Inde irae [hence his anger]. There is also Chorley in the Athenaeum who is rather playing the part of Scudo, because he was unable to extract from Beale le scudi [the money] he was demanding for the English translations of the new works we are performing (this is confidential!…). But this does not spoil anything, there is all-round success and I am at the centre of things. At the moment I am preparing Beethoven’s Choral Symphony which up till now has only been badly performed here. Would you believe that almost all the critics are hostile to La Vestale, the finest passages of which we performed grandly the day before yesterday? I had the weakness of being heart-broken at this lapsus judicii [error of judgement] … as though I did not know that nothing is equally beautiful, or ugly, or true, or false for everybody. As though the ability to understand certain works of genius is not of necessity refused to entire peoples…

I am almost ashamed of being so successful… All this is between us. […]

A letter of 12 May to the composer Gounod tells at greater length of the critical response of Chorley to Berlioz’s music and raises at the same time the delicate question of how Mme Pleyel reacted to Berlioz’s conducting of Weber’s Konzertstück (CG no. 1484):

[…] I very much regret that Rocquemont [Berlioz’s copyist] went to bludgeon you on the subject of Chorley and more still that you have written to Chorley. I don’t know what is the matter with him, but whatever the case I do not want to object to anything he has written against me: that is his right as a critic. I saw him at home a few days after my arrival; he received me very courteously and told me that he would shortly be arranging a dinner with friends to which I was invited in advance. Since then he has come down on Romeo, on the Philharmonic Society, and on its conductor; when he sees me he avoids me etc. etc. As a result we seem to be at loggerheads, which I greatly regret, though for my part I am not in the least annoyed with him. He was saying recently in the Athenaeum that the more he heard my music the less he understood it, that he could not see anything in it etc. etc. It is for me a misfortune for which I console myself with the thought that I share it with all artists of any originality and worth. The fact is none of them were ever able to please everyone at any time or in any place. You know this yourself. But when Chorley claims acrimoniously that I did not conduct well the Weber Concerto played by Mme Pleyel, there are 2000 members of the audience who could testify to the exactness, verve and finesse of the performance of this masterpiece in our third concert.

Even granting that Chorley found this performance bad, which I am perfectly prepared to admit, he was not obliged to mention this in his article, and had he been in the least way well-disposed towards me he would have kept quiet on the matter, which is something we do in circumstances that are even less important than these. There is therefore something I do not know which has prejudiced him against me. But I will not try to find out what it is, and if you wish to oblige me greatly, you will not say anything more to him about this.

Fortunately the entire press is extraordinarily warm in the opposite direction and Chorley is only supported by M. Hogarth (another one of my former friends), a very kind and very respectable old gentleman who unfortunately now happens to be the secretary of the old Philharmonic Society which we are trouncing (inde irae [hence their fury]), and besides has no real understanding of the ways of the modern Muse.

Tonight I am conducting Beethoven’s Choral Symphony. Here it has always been massacred; I hope it will go well for the first time. We have done five rehearsals, and it is a large undertaking. […]

Ten days after the fourth concert Berlioz wrote to d’Ortigue (CG no. 1488, 22 May):

[…] You write to me about the expenses of our concerts here; they are indeed enormous, and the organisers are losing money as are those of all musical institutions in London this year. But they knew in advance that this would be the case, and make so little mystery of the fact that in the programme of the last concert Beale* mentioned to the public the expenses caused by the rehearsals for Beethoven’s Choral Symphony which used up over a third of the subscription.

Nevertheless he regards these expenses as an initial investment and his intention still is to continue next year, though after getting rid of a certain individual who has an interest in the enterprise and who stands in our way. I will tell you about this in detail when I am back.

The Choral Symphony, which had never worked well here, produced a miraculous effect, and I scored a great success as a conductor. I was recalled after the first part of the concert. It was such an event that many doubted that we would emerge with credit from this formidable and wonderful work. That same evening Mlle Clauss played Mendelssohn’s G minor Concerto with wonderful purity of style, expressiveness and finish; she was asked to repeat the adagio. This child is now regarded in London as the best musician-pianist of our time, in spite of the intrigues of the Pleyel woman. Do not fail to mention Mlle Clauss and the Beethoven Symphony in your next feuilleton. […]

*But do not say a word about this to the French public.

The rivalry between Mlle Clauss and Mme Pleyel is also mentioned in a letter to Liszt of 7 June (CG no. 1491).

No letter survives concerning the fifth concert. Two days after the sixth and final concert Berlioz wrote to his sister Adèle (CG no. 1493, 11 June):

[…] I am in a state of intoxication after a success the like of which has never been seen in London, according to what the English say.

Our last concert was a triumph. My excerpts from Faust were encored and played again in a storm of applause, and then this immense audience called me back I know not how many times, crowns were thrown at me, and the cheers of the orchestra and the chorus etc., and the newspapers. In short a furious success. I wanted to write to you yesterday, but that was impossible. For a start I slept for half of the day, then the visits did not allow me a moment of freedom. Today it has been almost the same story. […]

Then the next day to d’Ortigue (CG no. 1495, cf. 1496):

I am writing to you just a few lines to say that our last concert took place last Wednesday with extravagant success, a huge crowd and large takings. I was called back four or five times. Two pieces of Faust were encored amidst shouts and stamping, and the English papers say that a musical success of such violence is unexampled in London. In short this is phenomenal. After the Chorus of Sylphs a crown was thrown to me; this success therefore has its laurels, as warriors say, and wreaths of oak and all St John’s herbs. I wanted to leave yesterday and then tomorrow. And yet I am staying for a few more days unless I am able to free myself of the remaining commitments, visits, dinners, letters of thanks etc…

Yet this prolonged stay worries me from the financial point of view; I have to pay so much rent in Paris, there are the expenses of my son who is now there, etc., so the luxury of living in London when I have nothing more to do there would be crushing. But in truth it is not altogether a luxury, because there is real disadvantage in leaving England at the point where I could see so many things coming up here.

A naive amateur from Birmingham was recently regretting he had not been able to get me to come and direct this year the Festival in his province. It is a great pity for us, he was saying, because it appears that M. Berlioz is even superior to M. Costa.

I am really going to miss my magnificent orchestra, and the chorus. What beautiful women’s voices! I wish you had heard the Choral Symphony by Beethoven which we gave for the second time last Wednesday!… In truth the whole experience in the immense Exeter Hall was grandiose and imposing.

I will soon be forgetting in Paris all these musical joys to resume my stupid task as music critic, the only one left for me to perform in our beloved country. […]

Berlioz long remembered his performances of the Choral Symphony (cf. CG no. 3287, in October 1867).

![]()

After the failure of Benvenuto Cellini at Covent Garden on 25 June Berlioz’s friends in London and the musicians of the orchestra offered to Berlioz to put on a special concert in his honour in Exeter Hall without charging for their services, though the plan could not be carried through. The episode is mentioned in Berlioz’s Memoirs (chapter 59) and told in more detail in several letters (CG nos. 1612, 1613, 1615, 1616, 1619), as for example one to Liszt on 10 July, just after his return to Paris (CG no. 1617):

[…] The musicians of Covent Garden and of the New Philharmonic Society wanted to give me a proof of sympathy on this occasion. Some 220 got together to organise at no cost a vast concert at Exeter Hall; they formed a committee and opened a subscription for the tickets for the concert, which quickly raised nearly £200. But as they were unable to obtain Exeter Hall for the time when the concert was possible, the project had to be abandoned; the players had to leave London later to go to the Festival at Norwich. The subscribers then said they did not want to take their money back, and the Committee decided to devote the sum to the publication of the score of my Faust with an English text. A delightful idea, worthy of true artists, though it would have been a more direct protest if the Committee had voted to publish Benvenuto instead of Faust, but you cannot always think of everything. […]

![]()

In his 1855 visit, Berlioz gave two further concerts with the New Philharmonic Society at Exeter Hall, on 13 June and 4 July. The programme of the first concert was: (Part I) Henry Leslie, overture The Templar; Mozart, Symphony in G minor (no. 40); arias by Rossini and Mozart; Beethoven, Piano Concerto no. 5 in E flat (Mme Oury, piano) (Part II) Berlioz, Romeo and Juliet, excerpts; aria by Mozart; Venzano, Valse; Mozart, overture The Magic Flute

Detailed reports of the first concert survive in two letters of Berlioz, the first the day after the concert to the music critic Pier Angelo Fiorentino in Paris (CG no. 1980):

Yesterday my first concert with the New Philharmonic Society took place at Exeter Hall. I only performed three movements from Romeo and Juliet as part of a vast programme (an English programme). The reception I received was dazzling, and despite a host of mistakes in the playing the effect of my pieces was altogether stupendous. The instrumental movement from the Fête chez Capulet literally swept the audience off its feet, and for the first time since this symphony exists it was encored amid furious shouts and applause enough to make you dizzy. I must also say that as a whole it has never been put across with such élan. This huge orchestra with its 44 violins (etc.) seemed drunk with verve.

The Morning Herald, written by someone completely unknown to me, observes that the piece was encored with the most vociferate enthusiasm.

The Morning Post, written by one of my warmest admirers [Howard Glover], announces an article which he has not yet had time to write, and states that never before did I score such a success in England. Davison was unable to get his article printed tonight, and I was unable to see him. I only know that in the hall he displayed the greatest enthusiasm. So all is going well. Next time we are giving Harold with Ernst playing the solo viola. I am being urged to perform L’Enfance du Christ, but I do not have any singers, and the English translation is not yet finished. […]

P.S. The programme included also Mozart’s Symphony in G minor [no. 40], an overture by M. [Henry] Leslie [The Templar], three pieces sung by M. and Mme Gassier (she was warmly applauded) and Beethoven’s Piano concerto en E flat [no. 5] played by Mme Oury, etc. etc.

The second letter, two days later, was addressed to Gaetano Belloni, Liszt’s agent in Paris (CG no. 1981):

[…] Last Wednesday’s concert was exceptionally enthusiastic; I mean that the public gave me a welcome of incomparable warmth and understanding, given that the playing suffered greatly from the absence of the orchestra’s principals who had to play elsewhere and had themselves replaced with mediocrities. All the same the ensemble was satisfactory for everything that was not from my own composition. Neither Mozart nor Beethoven had anything to suffer. In addition my piece the Fête chez Capulet was rendered with such verve and such unbelievable inspiration that for the first time in its existence it was encored amidst shouts and applause of which you have no idea in Paris.

This huge Exeter Hall was overwhelmed by the experience.

So far there has only been one (excellent) article in the Morning Herald and the acknowledgement of an unprecedented success in the Morning Post. Davison writes to me that his article in the Times could not be included because of the news from Crimea, and he urges me to read the Musical World which I have not yet done. […]

In a letter of 7 June, a few days before the concert, Berlioz mentions meeting the amateur composer Henry Leslie in Regent Street, who said to him: ‘I am delighted to meet you, M. Berlioz; I wanted to visit you at home to find out why I cannot make head or tail of your music’ (CG no. 1976).

The concert was attended by Richard Wagner, who was in London at the same time as Berlioz (he had been asked to conduct the concerts of the Royal Philharmonic Society which Berlioz had been unable to accept). It is interesting to compare Wagner’s critical reaction to the concert in his correspondence and his autobiography with Berlioz’s own account.

No detailed account from Berlioz’s pen has survived of the second concert (see CG nos. 1991, 1999). The large programme was as follows. Part I: the March from Mendelssohn’s Athalie, a cavatina from Benedict’s The Brides of Venice, a piano concerto by Henselt (soloist, Klindworth), the cantata Tam O’Shanter by Glover, Mendelssohn 1st Symphony, and Beethoven’s overture to Fidelio. Part II included Berlioz’s Harold in Italy (Ernst, solo viola), arias by Meyerbeer (from Le Prophète) and Rossini, and ended with Praeger’s Abellino overture. Meyerbeer was present at the concert (on the concert see Ganz [1913], p. 138). This was the last concert Berlioz ever conducted in Exeter Hall.

![]()

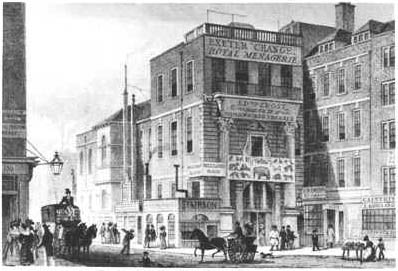

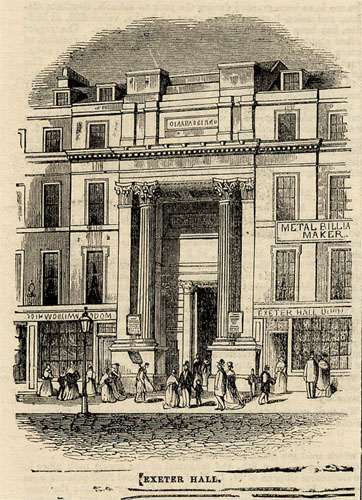

Exeter Hall was built between 1829 and 1831 on the site of the Exeter Exchange, which had itself been built in the 17th century in the reign of William and Mary on the site of the gardens of Exeter House, the town residence of the Bishops (or Earls) of Exeter. Exeter Hall was intended to provide a suitable place for the meetings of religious and charitable institutions, which previously held their meetings in banqueting rooms and taverns. It opened on 29 March 1831. Although designed initially for religious and charitable purposes, it was also used for music. In 1834 the Sacred Harmonic Society gave concerts in the smaller of its two halls, and following the establishment of singing classes in 1841 in the hall, the decade 1840-50 saw a series of popular Wednesday concerts, whose programmes included symphonies by Haydn and Mozart. The New Philharmonic Society, founded in 1852, gave its first concerts there under the direction of Berlioz.

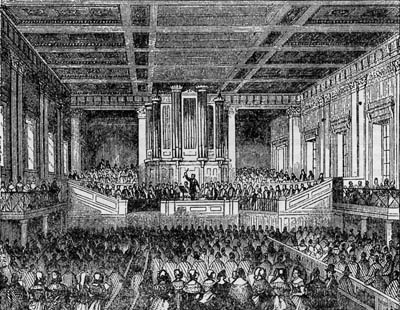

The hall was very large – it could hold over 3000 people, and was the largest concert hall available in London at the time, as Berlioz noted (CG no. 1451). He thought in fact that it was too large (CG no. 1449), and his preference generally was for smaller halls with a more favourable acoustic, such as the Conservatoire in Paris. On the other hand concerts given in Exeter Hall with large forces could acquire a special grandeur and sense of occasion, and this was true of a number of concerts Berlioz gave there (CG nos. 1492, 1495, 1496, 1542, 1981).

In 1882 the building, which had ceased to be financially profitable as a concert hall – it was too large to fill easily – was sold to the Young Men’s Christian Association and in 1907 it was demolished; the Strand Palace Hotel was built on the site.

(For further details on Exeter Hall and its history see our source: Elkin, 1955.)

![]()

The modern photos reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in 2001; other pictures have been scanned from engravings, postcards, and books (Ganz, Carse and Elkin) in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

This engraving is reproduced on a 1905 postcard.

The main entrance of Exeter Hall, in the Strand was narrow but high. The portal was flanked by two Corinthian pillars above which was sculptured in Greek letters the word Philadelpheion [Brotherly love]. A flight of stone steps from the pavement would lead to the Great Hall.

This engraving was published in The Illustrated London News.

The Great Hall was 138ft long, 90ft wide and 48ft high, and was lighted by eighteen large windows, with accommodation for 3000 people in the auditorium and 500 on the platform. Underneath the Great Hall was a smaller hall.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.