![]()

|

|

|

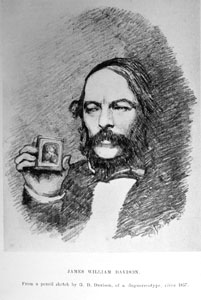

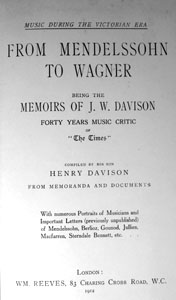

Unlike Charles Hallé and Wilhelm Ganz, James Davison did not write memoirs of his own; but left a large number of documents and letters. On the basis of these his son Henry Davison compiled posthumously an account of his father’s career as music critic under the title From Mendelssohn to Wagner (London, 1912). The book is valuable notably for the citation of numerous letters from or to contemporaries of Davison. With one exception, all the letters of Berlioz to Davison that are known are only to be found in this book, and the whereabouts of the originals is not known. This page reproduces all these letters, together with the translations provided in the book, a copy of which is in our collection. The typography and spelling of the original publication have been preserved, though obvious typographical and other errors have been corrected. The letters have been listed with the number and dating as reproduced in Correspondance Générale (abbreviated CG – note that a few letters are incorrectly dated in Davison’s book, to which page references are added).

From Davison’s book it emerges that his father kept a diary, but only one excerpt relating to Berlioz is quoted by him, in connection with Berlioz’s first trip to London in 1847. It is reproduced here in full before the letters of Berlioz that are cited later in the book.

Davison’s obituary notice on Berlioz in The Musical World of 13 March 1869, reprinted on pp. 501-2 of the above book, is reproduced elsewhere on this site.

![]()

Early in September [1847] Davison went to Paris and remained there, excepting a rapid run to and from the Gloucester Festival, until December. In Paris he witnessed Alboni’s début at the Académie Royale, and expected that of Miss C. A. Birch on the same stage, but was, after many delays, disappointed. Miss Birch fearing at the last that her defective pronunciation of French would expose her to ridicule. There he cultivated the acquaintance of Jules Janin and Fiorentino, Vivier (like the ancient mariner, buttonholing the unsuspecting stranger with the recital of the history of a mythic “Pietro”), Hallé, Balfe, Stephen Heller, Meyerbeer and Berlioz. There he went from theatre to theatre, from boulevard to boulevard, sometimes accompanied by his once arch-antagonist, Grüneisen. There he dined with Panofka, sumptuously, and with Carlotta Grisi and Vidal, whom he joined in reading from Voltaire’s poems. There he had a copious draught from the cup offered by Parisian artistic, literary and Bohemian life and withal wrote each week long and lively letters to the “Musical World.” On November 10, just after despatching one of these, the news reached him of Mendelssohn’s death….

The expression of Parisian musical regret was general. A group of artists, including Stephen Heller, Hallé and Panofka, signed a memorial addressed to Mendelssohn’s widow, in the name of the German musicians resident in Paris. Chopin was applied to for his signature and not unnaturally refused. “La lettre venant des Allemands, comment voulez vous que je m’arroge le droit de la signer?” This reply jarred on Davison’s highly-strung feelings and irritated him into some acrimonious remarks.

Presently the stream of youth, health, strength and spirits had resumed its interrupted course, flowing over everything, until, early in December, he prepared to return to London. Berlioz had already been there a month, having come over to take the direction of Jullien’s operatic enterprise at Drury Lane. There had been some talk, too, of his giving grand concerts at Covent Garden Theatre as early as November. Davison, in returning from Paris, was to escort the lady who after became Berlioz’ second wife [Marie Recio]. To quote from the last pages of a commonplace book that he was keeping at this time, under day Monday, December 5.

“Arrived at Boulogne at ¼ to 5, had some brandy and ham – some difficulty to find my passport – went to bed at ¼ to 6 – rose at 7 ¼ – found Mrs. Berlioz – a dreadful rainy morning – went to steamboat and embarked – passage awful – 7 hours at sea – couldn’t get into Folkestone – obliged to land at Ramsgate – went with Mad. B. to Castle Inn (both of us suffered horribly from sickness) – then had some soup, wine, etc., and dressed – thought I had lost Jarrett’s Horns, but found all right – quarrel between the two innkeepers (rivals) next door – got off by express at ½ 3 (22/6), reached London at 6 ½ and found Berlioz ready to meet us at the station – off in cab and arrived in time to get to Drury Lane Theatre and hear a great part of the opera (see M. W.) – saw Ella, T.; Chappell, Bodda, Miss Bassano, M. Seguin, wife and father-in-law – Albert Smith, etc. etc. etc. Markwell at theatre – Costa, Gruneisen and Webster in box opposite. After opera Mad. B. went away with B. Met Benedict at the door and walked with him to the French plays, round the Drury Lane and Strand way – raining – talking of Mendelssohn all the way – Benedict inconsolable – and told me 100 interesting things of poor Mendelssohn.”

![]()

Mon cher Davison,

Ne mettez pas dans mon programme, je vous prie, le nom de Miss Birch; je n’ai rien à lui faire chanter; et après avoir été annoncée, cela lui ferait peut-être de la peine de ne pas figurer dans le concert.

Nous essayerons une répétition générale des deux parties de Faust, mardi prochain; si vous pouvez, venez à Drury-Lane, à midi ½. Les chœurs me donnent bien de la peine; l’habitude qu’ils ont de chanter ces damnées rapsodies italiennes à deux parties, et même à l’unisson, les a gâtés.

Enfin, avec du temps nous arriverons.

Aidez-moi seulement, et reportez sur moi un peu de l’intérêt que vous portiez à Mendelssohn. Adieu, adieu, tout à vous.

H. BERLIOZ

Vendredi.

My dear Davison – Do not put Miss Birch’s name in my programme; I have nothing for her to sing; if her name were to appear in theprogramme she might be vexed at not appearing at the concert. We are going to try a full rehearsal of two parts of “Faust” next Tuesday; if you can come to Drury Lane at half-past twelve. The chorus give me a great deal of trouble; their habit of singing those damned Italian rhapsodies in two parts or, even, in unison, has spoilt them. However, we shall succeed in time. Help me, only, and give me a little of the interest you gave Mendelssohn. Farewell, farewell. Yours ever, H. Berlioz. Friday.

![]()

Mon cher Davison,

Je n’ai lu qu’hier votre bienveillant article du “Musical World” et je vous en remercie, il est écrit dans le sens qui peut m’être ici le plus utile et j’y vois de votre part des dispositions amicales dont je suis bien touché et bien reconnaissant. Adieu, je vous serre la main.

H. BERLIOZ.

Lundi, 14.

Jullien annonce mon second concert avec le même programme pour Jeudi, 24 Février.

My dear Davison – It was not till yesterday that I read your kind article in the “Musical World,” for which I thank you, it is written in a way that can be most useful to me over here, and shows a friendly feeling on your part for which I am very touched and grateful. [“Adieu, je vous serre la main” means] Yours sincerely, H. Berlioz. Jullien has announced my second concert with the same programme for Thursday, February 24.

![]()

17 Mars, 1848.

Mon cher Davison,

Je suis obligé de chercher à me tirer d’affaire ici comme je puis, maintenant que tout art est mort, enterré et pourri en France. En conséquence, en attendant que je puisse tirer parti de ma musique, peut-être, avec votre aide parviendrai-je à employer ma prose utilement. Veuillez donc vous informer auprès de l’Editeur du “Times”de la possibilité qu’il y aurait d’imprimer dans ce Journal des articles de moi (inédits) traduits par vous en Anglais; et sachez ce que cela nous rapporterait à tous les deux. J’ai fait une partie de mon voyage en Bohême, que les Débats possèdent depuis deux mois sans l’imprimer, l’impatience me prend et si le “Times” veut m’en donner un prix raisonnable je la lui céderai, et je finirai ce travail immédiatement. C’est romanesque, bouffon, et cela contient une critique assez drôle des mœurs musicales et Paris, avec quelques mots sur Londres. Adieu, soyez assez bon pour vous occuper de cela. Votre tout dévoué.

H. BERLIOZ.

P.S. – Je vous ai cherché comme un diamant dans le sable l’autre soir à Exeter Hall. Je voulais vous dire ce que vous savez aussi bien que moi, que la Symphonie de Mendelssohn est un chef d’œuvre frappé d’un seul coup, à la manière des médailles d’or. Rien de plus neuf, de plus vif, de plus noble et de plus savant dans sa libre inspiration. Le conservatoire de Paris ne se doute seulement pas que cette magnifique composition existe, il la découvrira dans dix ans.

My dear Davison – I am obliged to get along as best I can, now that all art in France is dead, buried and rotten. And so, until I am able to do something with my music, perhaps I might, with your help, be able to do something with literature. Would you then kindly sound the editor of the “Times” as to the possibility of his printing some (unpublished) articles of mine, to be translated into English by you, and find out what we should both get. There’s part of my Bohemian journey, which the Débats has had for two months without printing it. I am losing patience and if the “Times” can offer me a fair price. I will part with the work and finish at once. It is romantic, farcical, and contains some fairly funny criticism of Parisian musical manners, and a few words on London. Good-bye. Don’t forget this. Yours ever, H. Berlioz.

P.S. – I sought you as a diamond in the sand, the other night at Exeter Hall. I wanted to tell you what you know as well as I do, that that Symphony of Mendelssohn’s is a masterpiece, stamped, as gold medals are stamped, in one stroke. The fullness of his inspiration has given us nothing fresher, more spirited, more noble, more masterly. The Paris Conservatoire is not even aware of the existence of this magnificent work, it will make the discovery in ten year’s time.

![]()

Monsieur le rédacteur,

Permettez-moi de recourir à votre journal, comme à celui qui s’occupe exclusivement des choses musicales, pour exprimer en quelques mots des sentiments bien naturels après l’accueil que j’ai reçu à Londres. Je pars, je retourne dans ce pays qu’on appelle encore la France et qui est le mien après tout. Je vais voir de quelle façon un artiste peut vivre ou combien de temps il lui faut pour mourir au milieu des ruines sous lesquelles la fleur de l’art est écrasée et ensevelie. Mais quelle que soit la durée du supplice qui m’attend, je conserverai jusqu’à la fin le plus reconnaissant souvenir de vos excellents et habiles artistes, de votre public intelligent et attentif, et de mes confrères de la presse qui m’ont prêté un si noble et constant appui. Je suis doublement heureux d’avoir pu admirer chez eux ces belles qualités de la bonté, du talent, de l’intelligente attention unis à la probité de la critique; elles sont l’indice évident du véritable amour de l’art et elles doivent rassurer tous les amis de ce pauvre grand art sur son avenir, en leur donnant la certitude que vous ne la laisserez pas périr. La question personnelle est donc ici seulement secondaire car vous pouvez me croire, j’aime bien plus la musique que ma musique et je voudrais qu’il m’eût été donné plus souvent l’occasion de le prouver.

Oui, notre muse épouvantée de toutes les horribles clameurs qui retentissent d’un bout du continent à l’autre me paraît assurée d’un asyle en Angleterre; et l’hospitalité sera d’autant plus splendide que l’hôte se souviendra plus souvent qu’un de ses fils est le plus grand des poëtes, que la musique est une des formes diverses de la poésie, et que, de la même liberté dont usa Shakespeare dans ses immortelles conceptions, dépend l’entier développement de la musique de l’avenir.

Adieu donc vous tous qui m’avez si cordialement traité, j’ai le cœur serré en vous quittant, et je répète involontairement ces tristes et solennelles parole du père d’Hamlet: “Farewell, farewell, remember me.”

HECTOR BERLIOZ.

Sir – Permit me to have recourse to your journal, as that which concerns itself exclusively with matters musical, in order briefly to express feelings which are natural enough after the reception given me in London. I am going away, I am returning to the country which is still called France, and which, after all, is my own. I shall see by what means an artist may be able to live, or how long it will take him to die amidst the ruins under which the flower of arts is crushed and buried. But, how long soever be the suffering that awaits me, I shall, to the end, keep a most grateful recollection of your excellent and accomplished artists, of your intelligent and attentive public, and of those fellow journalists of mine who have given me such a chivalrous and constant support. I am doubly happy at being able to admire in them, those great qualities, kindliness, capability, intelligent attention united with honesty of criticism; those are the unmistakable sign of a real love for art and should reassure all lovers of poor great art as to her future, by comforting them with the certainty that you will not let her perish. Hence the personal question is only secondary, for, believe me, Music is much dearer to me than my music, as I wish I had had more opportunity of proving. Yes, our Muse, appalled by all the horrible clamours resounding from one end of the continent to the other, seems to me sure of a shelter in England; and the hospitality offered will be the more splendid, the more the giver of it remembers that one of her sons is the greatest of all poets, that music is one of the various forms of poetry, and that, on the very same freedom which Shakespeare allowed himself in his immortal conceptions depends the whole development of the music of the future. Farewell then to you all who have treated me so kindly, my heart is full at leaving you, and there rise to my lips those sad and solemn words of Hamlet’s father: “Farewell, farewell, remember me.” Hector Berlioz.

![]()

Il n’y a presque plus moyen de vivre dans notre infernal pays, et dans peu on n’y pourra plus vivre du tout.

It has become almost impossible to live in our infernal country, presently it will be quite impossible.

![]()

Mon cher Davison,

Can you have two places for us in your Box for the Wagner’s Début?

If I have not an answer to-morrow, I will understand an impossibility.

Thousand friendships,

Your,

H. BERLIOZ.

![]()

PARIS, 11 Septembre, 1852.

19, RUE DE BOURSAULT.

Mon cher Davison,

Richaut vient de publier une nouvelle ouverture que j’ai pris la liberté de te dédier. Je te l’envoie. Bonjour! Quid novi? Que devient-on à Londres? Te verra-t-on à Paris? On me l’avait fait espérer le mois dernier. J’ai été gravement malade, me voilà sur pieds. Donne moi de tes nouvelles. Milles amitiés.

H. BERLIOZ.

P.S. L’association des musiciens de Paris organise pour le 10 Octobre une grande exécution de mon Requiem dans l’Eglise de St. Eustache. Je vais à Weimar le 10 Novembre entendre mon opéra de Benvenuto. Voilà toutes mes nouvelles. Bonjour et amitiés à Jarret[t]. Est-il à Londres?

Paris, September 11, 1852. 19, Rue de Boursault. My dear Davison – Richault has just published a new overture of mine which I have taken the liberty of dedicating to you. I am sending it to you. How are you? Quid novi? Now are things going on in London? Is there any chance of seeing you in Paris? I hoped there was, from what I heard last month. I have been very ill, but I am on my legs again. Let me have news of you. Yours ever, H. Berlioz.

P.S. – The Society of Parisian Musicians are getting up a grand performance of my Requiem in the church of St. Eustace for October 10. On the 10th of November I am off to Weimar to hear my “Benvenuto.” That’s all my news. Remember me to Jarrett. Is he in London?

![]()

3 Juin.

17, OLD CAVENDISH STR.

Cher Davison,

Je n’ai pas le temps d’aller te serrer la main et te remercier du bel article du Times, mais tu ne doutes pas du plaisir qu’il m’a fait. Cela prépare à merveille la grande affaire de Covent Garden.

Les chanteurs commencent à comprendre leurs rôles, et nous marcherons je l’espère dans une quinzaine de jours. Tout à toi.

H. BERLIOZ.

June 3. 17, Old Cavendish Street. Dear Davison – I haven’t time to come and shake hands with you and thank you for your capital “Times ” article. I needn’t tell you what pleasure it gave me. It paves the way splendidly for the great Covent Garden affair. The singers are beginning to understand their parts, and, in a fortnight or so, we shall be in working order. Yours ever, H. Berlioz.

![]()

The concert cannot take place. The gentlemen of the committee organised to get it up, have conceived the delicate, charming and generous idea of devoting the sum realised by the subscription opened for the concert to the acquisition of the score of my ‘Faust,’ which will be published, with English text, under the superintendence of Beale, and other members of the committee. It would be impossible to be more cordial and artist-like at the same time; and I rejoice at the result of the performance at Covent Garden, since it has been the cause of a demonstration so sympathetic, intelligent and worthily expressed. Give all the publicity in your power to this manifestation; you will render justice to your compatriots, and, at the same time, confer a very great pleasure on

Yours, etc.,

HECTOR BERLIOZ.

![]()

Nous venons d’exécuter pour la 1ère fois à Brunswick ton ouverture du Corsaire, qui a très bien marché et produit beaucoup d’effet. Avec un grand orchestre et un chef au bras de fer pour le conduire ce morceau doit se présenter avec une certaine crânerie.

We have just performed your overture, the “Corsair,” at Brunswick; it went very well and was very effective. With a large orchestra and an iron-armed conductor, it’s a piece that isn’t without a sort of swagger of its own.

![]()

Mon cher Davison,

Une place est vacante à l’académie des beaux arts par suite de la nomination d’Halévy au poste de secrétaire perpétuel. Je me suis mis sur les rangs. J’aurais des chances si j’obtenais la voix d’Auber. Il pousse Clapisson!!! Veux tu avoir la bonté de tâcher par une lettre de décider Auber en ma faveur. Peut-être ne tient il guère à son protégé. En tout cas je puis lui être utile et je ne me trouverai jamais entre ses jambes pour le gêner dans ses opérations Lyriques comme fait et fera Clapisson.

L’assemblée est pour Samedi prochain, il sera important qu’Auber reçut ta lettre auparavant.

Mille amitiés bien vives,

Ton dévoué,

HECTOR BERLIOZ.

P.S. J’ai à t’envoyer un exemplaire de la grande partition de Faust qui vient de paraître; et qui n’a pas obtenu un succès équivoque à mon dernier voyage à Dresde, ainsi que l’a dit le “Musical World” mal informé.

Mardi, 8 Août

19, RUE DE BOURSAULT.

(AUBER 24, RUE ST. GEORGE).

My dear Davison – There is a vacancy at the Academy of Fine Arts due to Halévy’s appointment as permanent secretary. I am a candidate. I should have a chance if I got Auber’s vote. He is supporting Clapisson!!! Do you mind writing to Auber and trying to get him on my side? He may not be so very interested in his protégé. Anyhow, I might be useful to him and I could never obstruct his lyrical enterprises as Clapisson does and must continue to do. The meeting takes place next Saturday. Auber should receive your letter before then. Kindest regards from yours sincerely, Hector Berlioz.

P.S. – I have got to send you a copy of the full score of “Faust,” which has just come out; and which, on my recent visit to Dresden, obtained no “equivocal success” as stated by the “Musical World” on incorrect information. Tuesday, August 8. 19, Rue de Boursault. (Auber, 24, Rue St. George).

![]()

Mon cher Davison,

Voici ma partition que Barret[t] a la bonté de te porter. Je n’ai pas pu trouver plus tôt une occasion pour te l’envoyer.

Tu avais raison deux mille mois de te refuser à écrire à Auber. Mais on m’avait si fort prêché la platitude que je m’étais résigné à tout; et cela pour rien, car je savais bien l’inutilité de mes humiliations. Clapisson est nommé. N’y pensons plus. Adieu je te serre la main.

Mille amitiés sincères,

H. BERLIOZ.

Paris, September 8, 1854. My dear Davison – Here is my score, of which Barrett is kind enough to be the bearer. I haven’t had an earlier opportunity of sending it you. You were two thousand times right in refusing to write to Auber. But platitude has been so preached to me that I had resigned myself to everything; and all for nothing, for I foresaw the uselessness of my humiliations. Clapisson has been elected. We’ll think no more about it. Good-bye for the present, and kindest regards from yours sincerely, H. Berlioz.

![]()

PARIS,

Mercredi, 15 Décembre.

Mon cher Davison,

Il faut que je te dise que l’Enfance du Christ a obtenu Dimanche dernier un succès extraordinaire (Pour Paris surtout). Je t’écris cela non pas pour que tu le dises, mais seulement pour que tu le saches et parce que je suis sûr qu’il y aura pour toi plaisir à l’apprendre.

Tu me manquais dans cette salle en émotions…. Glover, qui a entendu la répétition générale et l’exécution, m’a écrit hier une ravissante et cordiale lettre en me demandant la partition qu’il a à cette heure entre les mains. L’exécution me semble vraiment avoir été belle et bonne, j’ai trouvé précisément les chanteurs qu’il fallait pour mes personnages.

Nous donnons le 2me. concert Dimanche, 24 Décembre à 2 h. Mr. Bowlby, que je viens de rencontrer, me fait espérer que tu seras alors à Paris. Ce serait trop de joie.

Adieu je te serre la main.

Ton dévoué,

H. BERLIOZ.

Paris, Wednesday, December 15. My dear Davison – I must tell you that “L’Enfance du Christ,” last Sunday, made an extraordinary success (for Paris especially). I am telling you this, not that you may repeat it, but only that you may know it, and because I am certain that the news will give you pleasure. I missed you in that scene of emotion…. Glover, who heard the full rehearsal and the performance, wrote me yesterday a charming and cordial letter asking me to let him have the score, which he has now got. I think the performance was really a fine one, I had just the singers I needed for the parts. We shall give the second concert, Sunday, December 24, at two o-clock. Mr. Bowlby, whom I have just met, gives me hopes that you will be in Paris then. That would be too delightful. Good-bye for the present. Yours ever, H. Berlioz.

![]()

Mardi, 19 Décembre, 1854.

Mon cher Davison,

Je suis désolé, mais désolé réellement de t’avoir chagriné ou seulement contrarié; je n’avais pas pris tout à fait au sérieux ta recommendation, à cause d’une phrase qui se trouvait dans ta lettre et qui semblait prêter à un sens contradictoire. Sans cela je n’eusse pas employé la forme ironique à propos de la rentrée de la Lionne. Crois moi, je ne suis pas de la force de Diderot à qui l’on recommandait un tableau en lui disant: “L’auteur a plusieurs enfants et n’a d’espoir d’existence que dans le succès de son ouvrage – Ah, vous me placez dit-il, entre l’art et la famille, je me décide pour l’art, le tableau est détestable.” Non, tu m’aurais vu répondre: placé entre la vérité et l’amitié, je me décide pour le mensonge et reste l’ami d’un ami. Qu’importe d’ailleurs un mensonge de plus ou de moins! Veux tu que je te dise à la prochaine occasion qu’elle a du style, qu’elle ne se livre à aucune extravagance vocale, qu’elle possède toutes les qualités musicales qui siéraient si bien à son admirable voix? Parole d’honneur je le dirai; mais je n’irai plus l’entendre qu’une seule fois, car à la dernière j’ai souffert cruvellement.

Adieu ne dis pas que je ne t’aime pas car tu mentirais, comme je suis prêt à mentir pour te prouver le contraire.

Ton dévoué,

H. BERLIOZ.

Tuesday, December 19, 1854. My dear Davison – I am sorry, really sorry, to have grieved you or even merely vexed you; I hadn’t taken your recommendation quite seriously, because a phrase in your letter struck me as lending itself to a contradictory interpretation. Else I would not have adopted an ironical style in reference to the reappearance of the Lioness. Believe me, I am not up to Diderot’s mark when a picture was recommended to him on the ground that: “The painter has several children and his only hope of a bare livelihood depends on the success of his work” – “Ah,” said he, “you ask me to choose between Art and Family, well then, I am for Art, the picture is abominable.” No, I should have replied: “If I must choose between Veracity and Friendship, I am for Lying, and for remaining the friend of my friend.” Besides, what does a lie, more or less, matter? Do you want me to say next time that she has style, that she indulges in no sort of vocal extravagance, that she lacks not one of the musical qualities that would so well become her splendid voice? I’ll say it, on my word of honour I will; but I will go and hear her again once only, for, last time, she made me suffer “cruvelly.” Adieu. Don’t say I don’t love you, for if you did you would be a liar, as I am ready to be in order to prove the contrary. Yours ever, H. Berlioz.

![]()

LONDON,

Dec. 20, 1854.

Mon cher Berlioz,

Merci mille fois pour tant d’amitié – mais tu m’as tout à fait mal compris – Je ne me suis plaint que de “la forme ironique” que tu as employé – voilà tout. Pour tes opinions sur les arts et les artistes j’ai trop de respect, crois moi, pour que je te demande quoi que ce soit en fait de critique qui puisse les dérouter, contrarier, modifier même – (tes opinions – comprends tu? non pas les artistes). Quand je ne me trouve pas de ton avis, comme par exemple sur des illustres compositeurs tels que Gounod, Adam, etc., – ou bien sur des éminentissimes réveilleurs des fées comme Prudent, ou des grands chanteurs avec ou sans style comme Massol, etc., je suis toujours fâché – mais je me sens assez entêté pour rester Diderot à leur égard, malgré la famille – Je ne partage pas tes sentiments cette fois – Je crois que le mensonge ne se marie pas bien avec l’amitié.

Sois persuadé, mon cher Berlioz, que je n’ai jamais demandé à un de mes confrères de mentir pour moi – et que jamais je ne le ferai. Crois tu que je ne lise pas tes feuilletons? Je sais bien, que tu a toujours fortement critiqué Mdlle. Cruvelli – Donc tu peux bien imaginer qu’en lui confiant ma lettre pour toi ce n’était pas une guet-à-pens pour te faire changer de couleur à son égard. Mais tu aurais pu “l’éreinter” en lui disant sévèrement tous ses défauts de chant et de jeu – de cantatrice et d’actrice – Bref – pour l’amour de Dieu et de moi, si tu en as véritablement pour moi (menteur) restes chez toi quand elle chantera.

London, December 20, 1854. My dear Berlioz – Thank you, a thousand times, for so much friendship – but you have quite misunderstood me – I objected only to your “ironical style” – that’s all. For your opinions on art and artists, believe me, I have too much respect to ask you for anything in the shape of criticism that could upset them, contradict them, or even cause their modification (your opinions, you understand, not the artists). When I find myself obliged to differ with you, as, for instance, in the case of such illustrious composers as Gounod, Adam, etc. – or in that of such super-eminent awakeners of fairies as Prudent, or such great singers, with or without style, etc., I am always sorry – but I am obstinate enough to remain Diderot despite Family. There we disagree. I believe falsehood and friendship can’t go together. I assure you, my dear Berlioz, that I have never asked a fellow-critic to tell lies on my account – and that I never will. Do you suppose I don’t read your articles? I am well aware that you have always strongly criticised Mdlle. Cruvelli – so you might have been sure that the letter I gave her for you was not a trap to get you to change your tone. Anyhow, you might have criticised her to some purpose, and denounced all her faults as singer and as actress – in short – for the love of Heaven and of me, if you really have any love for me (liar), stop at home next time she sings.

![]()

PARIS,

23 Décembre, 1854.

19, RUE BOURSAULT.

Ce qu’il y a de sûr, très cher ami, c’est que tu viens de m’écrire quatre bonnes pages, toi qui jusqu’à présent ne m’avais jamais adressé que des billets de dix lignes tout au plus. A quelque chose malheur est bon. Mais je te répète que je suis tout à fait chagrin de t’avoir fait de la peine. J’ai été comme toi il y a vingt ans; j’avais une passion admirative pour Mme. Branchu et je ne lisais pas sans douleur ni même sans colère la moindre critique sur son talent. Voilà pourquoi je te comprends. Ainsi rappelle toi le passage de Shakespeare où Hamlet dit à Laërtes: Supposez qu’en décochant une flèche par dessus le toit d’une maison j’aie blessé mon frère par hasard.

Il faut que tu saches ce qui m’arrive: Je reçois avant-hier une lettre de Sainton me proposant un engagement pour aller diriger les huit concerts de la société Philharmonique. Or j’étais par malheur, et à de très modestes conditions, engagé depuis quinze jours avec Wilde pour 2 concerts de la New Philharmonic Society dans le courant de Mai. J’ai écrit à Wilde pour obtenir de lui qu’il me rende ma liberté, s’il n’y consent pas il faudra que je tienne ma parole, et je perdrai ainsi une magnifique occasion de me produire à Londres. C’est une véritable catastrophe pour moi. Qu’est-il donc arrivé? Comment Costa a-t-il quitté la direction de ces concerts? J’ignore tout cela complètement. Adieu, je suis obligé de te quitter pour aller faire une dernière répétition, mon deuxième concert ayant lieu demain.

Je te serre la main Brutus, et Cassius espère qu’après cette petite discussion ton amitié pour lui n’en sera que plus vive et plus solide; c’est du moins ce dont il peut répondre pour la sienne pour toi.

Ton dévoué,

H. BERLIOZ.

Paris. December 23, 1854. 19 Rue Boursault. – One thing is certain, dearest friend, and that is you have written me four full pages, you who, till now have been in the habit of writing me notes of ten lines at the outside. Misfortune has its consolations. Once more let me tell you that I am truly grieved at having vexed you. I was like you twenty years ago; I was consumed with a passion of admiration for Mme. Branchu, so much so that the least criticism of her talent caused me not merely distress but anger. That’s why I can understand you. You remember what Shakespeare makes Hamlet say to Laërtes: “That I have shot mine arrow o’er the house, And hurt my brother.” I must tell you what has happened to me: I got a letter the day before yesterday from Sainton offering me an engagement to conduct the eight concerts of the Philharmonic Society. Now, unfortunately I had been engaged by Wylde a fortnight before, for two concerts of the New Philharmonic in May, and at very low terms. I have written to Wylde asking him to release me; if he refuses, I must, of course, keep my word, thereby losing a magnificent opportunity of bringing myself forward in London. It’s a veritable catastrophe for me. But what’s happened? How has it come about that Costa has given up the conductorship? I am in entire ignorance. Good-bye, I must leave you, in order to attend a last rehearsal, my second concert taking place to-morrow. Shake hands, O Brutus. Cassius hopes that the little argument there bas been will but add life and strength to thy friendship for him; he can guarantee that that, at least, will be its effect on his friendship for thee. Thine ever, H. Berlioz.

![]()

13, MARGARET STREET.

Mon cher Davison,

Je suis arrivé Vendredi soir [8 juin], et je n’ai pas encore eu une minute pour aller te voir. Aujourd’hui encore je serai pris toute la journée par notre répétition générale et en rentrant, mouillé comme un rat de rivière, j’aurai probablement tout juste la force de venir me coucher. Mais en attendant demain bonjour! Je te serre la main.

J’ai eu à me débattre ces jours-ci contre une exécution impossible, que j’ai heureusement évitée en supprimant toute la première partie de Roméo et Juliette, qui t’eût fait saigner les oreilles. A cause de deux ou trois instruments à vent (d’un cor surtout) nous serons peut-être obligés aujourd’hui de supprimer le Scherzo.

Adieu, on fait ce qu’on peut, on n’est pas parfait le temps est un grand maigre, et autres proverbes de circonstance.

H. BERLIOZ.

Mardi matin

13, Margaret Street. My dear Davison – I got here Friday evening, and I haven’t had a minute to spare to go and see you. To-day, again, all my time will be taken up by our general rehearsal, and when I come home, dripping like a water-rat, I shall probably have just enough strength left to get to bed. But, pending to-morrow, how are you? I shake you by the hand. These last few days I have had to contend against an impossible execution, which luckily I have evaded by leaving out the whole of the first part of “Romeo and Juliet,” which otherwise would have made your ears bleed. Owing to two or three wind instruments (a horn, especially) we shall now probably have to leave out the scherzo. Good-bye, one does what one can, nobody’s perfect. Time is a big lean, beggarly rascal, and other suitable proverbs. H. Berlioz.

![]()

A Mr. l’éditeur du “Musical World.”

Monsieur,

Un des membres du chœur de la New Philharmonic Society me demande des explications au sujet de la suppression des chœurs de ma symphonie (“Roméo et Juliette”) au concert que j’ai dirigé à Exeter Hall le 13 de ce mois.

Les raisons qui m’ont obligé de faire cette suppression étaient évidentes et impérieuses.

Le petit chœur du Prologue, pour quatorze voix seulement, avait été étudié en langue Française, M. et Mme Gassier étant à mon grand étonnement engagés pour les solos de cette partie de ma symphonie qu’il leur était impossible de chanter en anglais. Or, au dernier moment M. Gassier, dont la voix est celle d’un Baryton, a déclaré qu’il ne pouvait chanter un rôle de Ténor, et que Mme Gassier (soprano aigu) ne pouvait chanter un rôle de Contralto; ce qui, pour moi, était évident.

Il fallait donc commencer de nouvelles études avec texte anglais, et ces chœurs extrêmement difficiles, dont les paroles doivent être bien prononcées, et sans accompagnement, ne pouvaient être suffisamment appris en si peu de temps.

Quant au chant des Capulets, pour lequel Messrs. les choristes hommes s’étaient donnés beaucoup de peine, il était bien su. Mais en apprenant qu’on avait maintenant l’habitude de faire exécuter les chœurs devant le public sans que les choristes eussent une seule fois répété avec l’orchestre, j’ai éprouvé une vive inquiétude. D’autant plus qu’un petit nombre de ces messieurs étant venus à la dernière répétition et ayant deux fois de suite manqué leur entrée après la réplique de l’orchestre, il était évident que ceux qui devaient chanter au concert, sans avoir jamais entendu l’orchestre (c’est à dire le grand nombre) manqueraient leur entrée à coup sûr. Pouvais-je les exposer à un aussi fâcheux accident? Pouvais-je exposer la Société Philharmonique à un désastre de cette gravité? Et pouvais-je m’exposer moi-même à voir un des morceaux principaux de mon ouvrage compromis dans une tentative pareille?

Je laisse aux artistes et à toute personne qui a quelque connaissance des choses musicales le soin de répondre.

Quant à moi je ne crois pas qu’on doive faire en public de pareilles expériences.

J’ai l’honneur d’être, Monsieur,

Votre dévoué serviteur,

HECTOR BERLIOZ.

LONDRES,

26 Juin, 1855.

To the editor of the “Musical World.” Sir – One of the members of the chorus of the New Philharmonic Society asks me for an explanation concerning the suppression of the choruses in my symphony (“Romeo and Juliet”) at the concert I conducted at Exeter Hall on the 13th instant. The reasons that obliged me to make the suppression were obvious and irresistible. The small chorus of the prologue, for fourteen voices only, had been learnt in French, Mr. and Mme. Gassier having been, to my great surprise, engaged for the solos of that part of my symphony, which they were unable to sing in English. At the last moment, Mr. Gassier, whose voice is that of a baritone, said that he could not sing a tenor’s part and that Mme. Gassier (high soprano) could not sing the part of a contralto, which to me was obvious. So that it would have been necessary to start afresh, learning the English text, and those extremely difficult choruses, the words of which have to be very distinctly pronounced, which, moreover, are unaccompanied, could not possibly have been sufficiently learnt in so short a time. With regard to the Capulet’s song, over which Messrs. the male choristers had taken great pains, it was well mastered. But when I heard that it was now customary to give public choral performances without the choristers having a single rehearsal with orchestra, I got extremely nervous. The more so because a few of these gentlemen, who did attend the last rehearsal, having twice missed their cue after the re-entry of the orchestra, it was evident that those who were going to sing at the concert without having heard the orchestra at all (the large number) would miss their cue with absolute certainty. Could I expose them to so vexatious an accident? Could I expose the Philharmonic Society to so serious a disaster? and could I expose myself to seeing one of the principal pieces of my work mixed up in such a perilous enterprise? I leave the reply to artists and to any person with some little knowledge of musical matters. For my part, I do not think such experiments should be made in public. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, Hector Berlioz.

![]()

Mon cher Davison,

Puisque tu ne reviens pas à Paris, subis ma lettre. Voudrais-tu avoir la bonté de voir Mr. Ullah et de lui demander comment il entend que nous nous arrangions Beale et moi avec lui, pour les répétitions et l’exécution de deux concerts à St. Martin’s Hall, en employant cent de ses choristes, vers le commencement de Mars. Beale court les provinces et ne songe pas à cela. Il faut donc que je me renseigne le plus tôt possible.

Les choristes de Mr. Ullah seront ils payés? et combien par répétition? S’il faut les payer j’aime mieux prendre les bons de Covent Garden, en petit nombre, et leur chef Smithson qui est le meilleur instructeur de chœurs que j’aie jamais vu. Peut-être pourrait-on combiner l’une et l’autre masse vocale; prendre le petit chœur de Covent Garden pour l’Enfance du Christ qui n’exige pas de masses puissantes, et lui adjoindre une petite armée d’Ullah pour le Te Deum, à un second concert.

En ce cas il faudrait, après être bien convenu de tout avec Mr. Ullah, lui envoyer les parties de chants du Te Deum sans retard, pour que ses élèves eussent le temps de bien les apprendre.

Quant à l’orchestre de 68 ou 70 musiciens qu’il me faudra, il sera facile de les réunir huit jours avant mon arrivée à Londres, et, avec deux répétitions, ces messieurs iront comme des lions; car je compte éviter les chiens et les chats.

Crois-tu que Henri Smart veuille se charger de la partie d’orgue dans le Te Deum?

Adieu, je suis un peu éreinté des batailles de l’Exposition, dans quelques jours je serai prêt à recommencer.

Ton dévoué,

H. BERLIOZ.

Mille amitiés indiscrètes.

19, RUE BOURSAULT,

30 Nov., 1855.

My dear Davison – Since you are not coming back to Paris endure my letter. Would you mind kindly seeing Mr. Hullah and asking him how he would like Beale and me to arrange with him about the rehearsals and performances of two concerts at St. Martin’s Hall, with a hundred of his choristers, towards the beginning of March? Beale is touring in the country and not thinking of these matters. So I have got to obtain particulars as soon as possible. Are Mr. Hullah’s choristers to be paid? and, if so, how much for each rehearsal? If they have to be paid, I should prefer having a small number of the good Covent Garden ones and their conductor, Smithson, who is the best chorus instructor I have ever met. Perhaps it would be possible to make some sort of combination of these two vocal bodies; using the little chorus from Covent Garden for “L’Enfance du Christ” which does not require powerful masses, and reinforcing it with a little army of Hullah’s for the Te Deum at a second concert. In that event, as soon as everything has been quite settled with Mr. Hullah, the choral parts of the Te Deum ought to be sent to him that his pupils may have time to learn them properly. As to the orchestra of sixty-eight or seventy musicians which I shall want it will be easy enough to get them together a week before my arrival in London and after a couple of rehearsals those gentlemen will go like lions; for I mean to eschew dogs and cats. Do you think Henry Smart would undertake the organ part in the Te Deum? Good-bye. I am rather knocked up with the battles of the Exhibition. In a few days I shall be ready to start again. Yours ever, H. Berlioz.

![]()

Mon cher Davison,

Sois bon enfant et cordial pour mon jeune ami Théodore Ritter; je n’ai pas besoin de te dire que c’est un pianiste compositeur grand musicien; au reste il ne te faudra pas grand temps pour reconnaître les sérieuses qualités de son talent.

Adieu, je suis malade, inquiet, triste, découragé, mais toujours ton dévoué et affectionné.

H. BERLIOZ.

April 20. My dear Davison – Be a good sort and kind to my young friend, Theodore Ritter; I need not tell you that he is a fine musician, pianist, composer; it won’t take you long to recognize the sterling qualities of his talent. Good bye, I am ill, troubled, disconsolate, discouraged, but ever your devoted and affectionate, H. Berlioz.

![]()

Cher ami,

Je t’envoie par l’intermédiaire de la maison Brandus ma petite partition de Béatrice. Je serais bien heureux qu’elle te fît plaisir. Je suis toujours plus ou moins malade ou tourmenté par diverses violences de ma pensée et de mon cœur. Qy’y faire? Rien, mais les témoignages d’affection de certains amis me sont bien nécessaires, et voilà pourquoi tu ferais une bonne action en m’écrivant. J’ai dîné avant hier chez les Patti où nous avons tout naturellement beaucoup parlé de toi. La charmante enfant a été beaucoup plus gracieuse et espiègle que jamais. Elle s’est trouvée, dit-elle, paralysée par son entourage dans le Don Giovanni; en effet tout le monde dit que cette reprise du chef d’œuvre est honteuse. Celle de la Muette au contraire (où les rôles sont pitoyablement chantés) a obtenu un grand succès. Le Conservatoire m’a demandé pour le 8 Mars le duo des jeunes filles, final du 1r. acte de Béatrice. Je ne sais si ce public hargneux et plein de préventions se laissera prendre comme celui de Bade à la mélancolie de ce morceau. Quoi qu’il en soit je serai bien aise de faire entendre cela aux artistes. Je suis sur le point de prendre un parti pour ma partition des Troyens. Si d’ici à huit jours le Ministre ne se décide pas à la mettre en répétitions à l’opéra, je cède aux instances de Carvalho et nous tentons la fortune au th: Lyrique pour le mois de Décembre. Il y a trois ans qu’on me berne à l’opéra; et je veux entendre et voir cette grande machine musicale avant de mourir. Tu penses bien que ce ne sera pas avec les ressources actuelles de ce théâtre que nous viendrons à bout d’une telle entreprise; mais on va chercher à composer une vraie troupe lyrique grandiose; et Carvalho prétend qu’il y parviendra. Dimanche prochain je dirigerai un demi programme au concert de la Société Nationale des arts. J’ai répété pour la première fois hier et je crois que cela marchera. Au commencement d’avril j’irai à Weimar diriger les premières représentations de Béatrice que la Grande Duchesse a demandée pour le jour de sa fête. En Juin il faudra que j’aille à Strasbourg diriger l’Enfance du Christ au Festival du Bas Rhin. En Août je retourne à Bade remonter Béatrice.

Voilà toutes mes nouvelles.

Des événements qui me préoccupent le plus je ne te dirai rien, il y aurait trop à dire. Je vis comme un homme qui doit mourir à toute heure, qui ne croit plus à rien et qui agit comme s’il croyait à tout.

Je ressemble à un vaisseau de guerre en feu dont l’équipage laisse le champ libre à l’incendie, attendant tranquillement l’explosion de la Sainte Barbe…. Oh! je voudrais te voir et causer à cœur ouvert avec toi; j’ai été bien longtemps à te connaître, et je te comprends maintenant. J’aime tant ton excellente nature d’artiste et d’homme! On m’a tant accusé d’être intolérant et passionné que je suis tout sympathie pour la passion et l’intolérance. Les êtres qui m’inspirent une antipathie insurmontable sont les raisonneurs froids qui n’ont ni cœur ni entrailles, et les fous qui n’en ont pas davantage mais qui manquent en outre de cerveau.

Je viens de recevoir de New York une lettre qui m’a vivement ému; c’est celle d’un jeune musicien américain qui me demande de lui écrire, parce qu’il a une carrière difficile et que le chagrin le tue. Il s’adresse mal pour trouver un consolateur; je vais pourtant lui répondre de mon mieux.

Cette lettre que je t’écris va peut-être te trouver dans quelque ennui, dans quelque tristesse, car nous avons tous une large part dans ce fatal domaine. Si le malheur veut qu’il en soit ainsi, attends pour me répondre une éclaircie; le temps n’est pas toujours à l’orage.

Adieu, cher ami, pardonne-moi mes divagations, et crois à la sincère et vive affection de ton dévoué

H. BERLIOZ.

4, RUE DE CALAIS,

PARIS.

Le 5 Février, 1863.

4 Rue de Calais, Paris, Feb. 5, 1863. My dear Friend – I am sending you through the Brandus firm my small score of “Beatrice.” I should be glad if you like it. I am, as usual, more or less ill or worried by various violences of thought and feeling. What then? Nothing, except that signs of affection from certain friends are very necessary to me, and that you would be doing a good action by writing to me. I dined the day before yesterday at the Pattis where, naturally enough, we talked a great deal about you. The charming girl is more graceful and sprightly than ever. She says that, in “Don Giovanni,” she was paralysed by her surroundings; indeed everybody says that this production of the masterpiece is shameful. That of the “Muette,” on the contrary (though the parts are wretchedly sung), has had great success. The Conservatoire wants, for the 8th of March, the duet of the two young girls, finale of the first act of “Beatrice.” I don’t know if that crabbed and prejudiced audience will, like the audience at Baden, be allured at all by the melancholy of the piece. Anyhow I should much like artists to hear it. I am on the point of coming to a resolution concerning my score of “Les Troyens.” If within a week’s time the Minister does not decide to begin rehearsals of it at the opera, I shall yield to Carvalho’s persuasions, and try our luck at the Lyric for December. For three years they have been shilly-shallying with me at the opera; and I do want to hear and see that big musical concern before I die. We shan’t, as I needn’t tell you, be able to accomplish such an enterprise with the actual resources of that theatre; but endeavours will be made to get together a really grand lyrical company; and Carvalho declares he can do it. Sunday I am to conduct half the programme of a concert at the Société Nationale des Arts. The first rehearsal was yesterday and I think all will go well. At the beginning of April I am off to Weimar to conduct the first performances of “Beatrice” which the Grand Duchess has asked for, for her fête day. In June I am due at Strasbourg to conduct “L’Enfance du Christ” at the Lower Rhenish Festival. In August I return to Baden to produce “Beatrice” again. There you have all my news. Of the events that pre-occupy me most I tell you nothing, there is too much to tell. I live like a man who may have to die at any moment, who no longer believes in anything, and who acts as if he believed in everything. I am like a warship on fire, whose crew let things take their course, quietly waiting for the powder magazine to blow up…. Oh! I do wish I could see you and open my heart to you; I was a long time getting to know you, and I now understand you. I like the stuff you are made of, both as artist and as man! I have been so often denounced as intolerant and passionate, that I am all sympathy for passion and intolerance. The beings that inspire me with insurmountable antipathy are the cold reasoners, destitute of both heart and bowels, and the fools, who, similarly destitute are destitute, also, of brains. I have just received, from New York, a letter that touched me deeply; a young American musician asks me to write to him because his career is beset with difficulties and grief is killing him. He has scarcely applied in the right quarter for consolation; however, I am going to answer him as well as I can. The letter I am writing to you now may chance to find you in some worry, some distress or other for we all of us have a liberal allotment in the same fateful domain. Should ill luck have it so, don’t reply to this until your sky has cleared; the barometer is not always low. Adieu, dear friend, forgive me these digressions, and believe me your sincerely affectionate, H. Berlioz.

![]()

Mon cher foutu paresseux!

Pour te punir de ta paresse, de ton manque de parole, de ton manque d’amitié, de ton manque de tout… je t’adresse encore un pianiste M. Pfeiffer qui est fort désireux de faire ta connaissance… Accueille-le bien. Nous montons les Troyens pour le mois de novembre. Adieu je te serre la main.

à toi H. Berlioz.

My dear confounded lazybones!

To punish you for your laziness, your want of faith, your want of friendship, your want of everything…. I am sending you another pianist, Mr. Pfeiffer, who is particularly desirous of making your acquaintance…. give him a good reception. We are getting up “Les Troyens” for November. Good-bye.

Yours ever,

H. BERLIOZ.

[A facsimile of the autograph is printed in Davison’s book facing p. 208, and is reproduced on this site.]

![]()

Viens, c’est pour Mercredi, 4 Nov. On m’a fait un succès terribe ce matin à la répétition. Tout va.

A toi,

H. BERLIOZ.

Come, it’s settled – Wednesday, November 4. At the rehearsal this morning the success was terrific. All’s well. Thine, H. Berlioz.

![]()

Cher ami,

M. Jacquart qui est engagé par Ella, me demande pour toi une lettre d’introduction. Il n’en a pas besoin, puisque son talent est incontestable, pur, noble, et musical: tu seras le premier à le reconnaître. Je lui donne cependant la lettre parce que c’est un prétexte pour t’envoyer mille amitiés, et parce que je suis bien sûr maintenant, ayant renoncé pour jamais à la critique, de ne plus donner à tes protégées d’éloges insuffisants.

Comment vas-tu, pauvre esclave, comment traînes-tu ton boulet, pauvre galérien? Quant à moi j’ai peine encore à croire à ma délivrance, et les premières représentations d’opéras Parisiens me font toujours peur… par habitude. Aussi avec quel bonheur et quel acharnement je m’abstiens d’y assister!….

Ne viendras-tu pas passer quelques jours cet été à Paris? Nous ferions des courses à la campagne avec les moins bêtes de nos amis, et même sans amis. Mais tu n’auras pas le temps, pauvre misérable! car c’est surtout pour toi que “the Times” is money. Tiens, fais-moi gagner un million, et si je ne t’en donne pas immédiatement les trois quarts et demi tiens moi pour un drôle.

Bonjour, je te serre la main.

H. BERLIOZ.

PARIS

ce 22 avril 1864

Paris, April 22, 1864. Dear Friend – Mr. Jacquart, who has been engaged by Ella, asks me for a letter of introduction to you. He needs none whatever, for his talent is unquestionable, pure, noble and musical; you will be the first to see it. Nevertheless I am giving him a letter because it’s an excuse to send you a hearty greeting, and because there is no danger, now that I have given up criticism for ever, of my bestowing insufficient praise on your protégées. How are you, poor slave; poor galley-slave, how are you getting along with your cannon-ball? As for me, I can’t yet quite realise that I am free, and the first performances of Parisian opera always give me a fright – by force of habit. With what joy, with what furious obstinacy do I abstain from attending them! – Can’t you manage to spend a few days in Paris this summer? We’d make excursions into the country with the least stupid of our friends, or even without any friends at all. But, poor wretch, you won’t have time! For you more than anyone the “Times” is money. Now look here, help me gain a million, and if I don’t immediately hand you over three and a half quarters of it, reckon me a rascal, etc., H. Berlioz.

![]()

See also on this site:

Berlioz in London

Berlioz in London: friends and acquaintances (James Davison)

Index of letters of Berlioz cited

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 1 March 2009.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the information on this page. All rights of reproduction reserved.