![]()

Biographers and critics: David Cairns

|

Biographers and critics: David Cairns

|

|

This page is also available in French

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.

![]()

David Cairns is the author of what is currently the most detailed and authoritative biography of Berlioz in existence. Cairns has written at different times for several London-based newspapers and periodicals, notably The Musical Times, the Times, the Sunday Times, the Evening Standard, the Financial Times, the Times Educational Supplement, the Spectator, and the New Statesman. He has also worked for the London branch of Phonogram (1967-1972), where he was involved in planning and carrying out large-scale recordings of Berlioz [the Colin Davis Berlioz cycle], Haydn, Mozart, and Tippett. He was Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of California at Davis, a visiting scholar at the Getty Center in Santa Monica, and a visiting fellow of Merton College, Oxford.

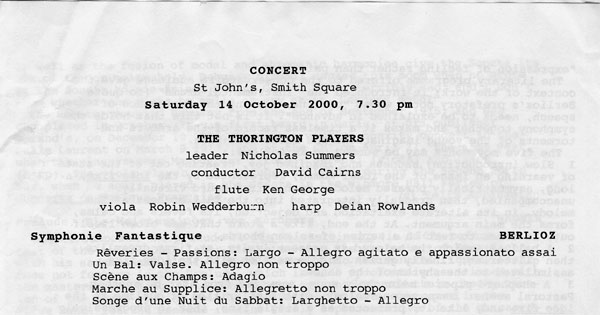

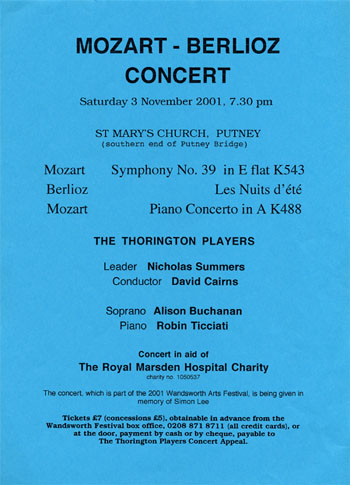

Together with Stephen Gray, David Cairns founded the amateur Chelsea Opera Group in 1950, which Colin Davis conducted in La Damnation de Faust, Roméo et Juliette and concert performances of Les Troyens and Benvenuto Cellini in the early 1960s, and of which Davis was president. The Chelsea Opera Group has also performed many of Berlioz’s major works over the years. David Cairns also formed in 1983 The Thorington Players, an amateur orchestra, which he conducts. The orchestra’s repertoire includes Haydn, Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Brahms, Sibelius, Bruckner, and Berlioz. David Cairns was made Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1991 in recognition of his services to French music, and created a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1997. He was made the Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2013. See below the speeches by H.E. Bernard Emié, French Ambassador to the United Kingdom, and David Cairns, given on this occasion at the French Embassy in London on 13 November 2013.

David Cairns relates in the Prologue of the first volume of his biography of Berlioz (pp. xvii-xviii) how he first discovered Berlioz’s music:

For a long time the music of Berlioz remained a sealed book to me. Each person comes to a particular composer in his or her own way and time; no rules govern the processes of musical discovery. But circumstances of cultural climate and environment may delay it. The more conditioned we are to the music we know, the more, subconsciously, we expect the unfamiliar to approximate to it. […] I remember, one day when I was in my early twenties, my sister coming home in great excitement with a recording of the Fantastic Symphony that she had just heard. She insisted on my listening to it then and there. It made absolutely no sense to me.

Nearly ten years passed before anything occurred to change this attitude. My musical tastes grew outwards from their Germanic centre but on the rare occasions when I heard any Berlioz I could make little sense of it. Then in 1957 Covent Garden produced The Trojans. I went to the dress rehearsal and the première. Unlike many, bouleversés by the experience (the origin of the modern Berlioz revival), I was only partly persuaded. But had I not to go abroad immediately after the first night I should certainly have returned to Covent Garden for a later performance. For by then my interest had been aroused. Not long before, a cousin had played me the old 78 recording by Jean Planel of “Le repos de la sainte famille”, from The Childhood of Christ and had lent me the Memoirs (in the Everyman edition, with its racy, sympathetic translation by Katharine Boult). I was charmed by the strange sweetness and the purity of the piece; and I was riveted by the book: the personality of the author intrigued and attracted me. I felt I must reconsider my rejection of his music and have another shot at it.

The opportunity came a few months later. The Chelsea Opera Group performed The Damnation of Faust, under Meredith Davies. I played in the orchestra, in the percussion section. We had half a dozen rehearsals. Gradually, in the course of them, the barriers fell away and enlightenment dawned – until I realized with delight that the language which ten years before had been so much gibberish to my musical understanding had become familiar and made sense, thrilling, unimagined sense after all.

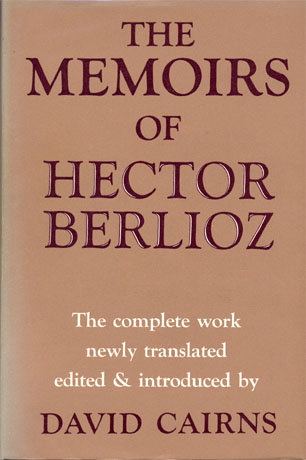

Cairns’ biography of Berlioz was preceded by his work on Berlioz’s own autobiography. In 1969, the first edition of his English translation of Berlioz’s Memoirs was published by Victor Gollancz to coincide with the centenary of Berlioz’s death. Berlioz’s Memoirs had been translated into English as early as 1884 by Rachel and Eleanor Holmes, which was revised and annotated by Ernest Newman in his 1932 edition of the book. However, it was David Cairns’ translation which did full justice to the Memoirs and made Berlioz’s own account of his life, complete and unabridged, known to the English-speaking world; the translation is supported with detailed critical notes and appendices. The work received at once deserved critical acclaim (see for example on this site the review by Gerald Abraham), and it has since been reprinted many times over, including in the Everyman’s Library Classics & Contemporary Classics series in 2002.

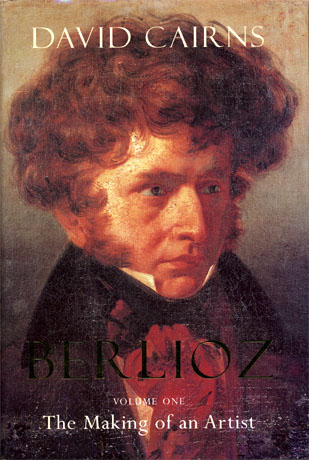

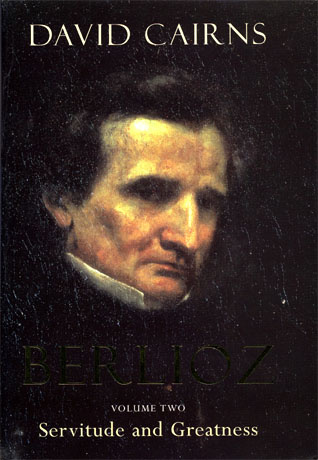

The full-scale biography of Berlioz followed as a natural sequel to the translation of the Memoirs. In 1989 the first volume was published (Berlioz: The Making of an Artist 1803-1832), and it was followed in 1999 by the second volume (Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness 1832-1869), together with the revised edition of the first one. The two volumes, over 1543 pages in all, were the result of many years of meticulous original research into Berlioz’s life through, among others, unpublished correspondence and documents, as David Cairns states in the Preface to volume one of the biography (p. xiii):

I … owe a profound debt of gratitude to Yvonne Reboul-Berlioz, who gave me unrestricted access to the large collection of family documents belonging to her late husband (a great-grandson of Berlioz’s sister Nanci) and made me welcome at her Paris apartment in the Rue du Ranelagh. It was in the many weeks spent going through the letters, diaries and account books of the Reboul Collection that I began to get a picture of the environment from which the composer sprang, and the idea of the book I should write about him first took shape.

The merits of Cairns’ magisterial biography of Berlioz are many: extensive documentation, breadth of historical vision, sympathetic appreciation of the composer coupled with objectivity of approach, fair-mindedness, and a natural elegance of style. The work commands immediate respect and trust, and has an unforced distinction that few other biographies of the composer can emulate. It was deservedly greeted with prizes, awards and appreciative reviews. The first edition of the first volume won the Royal Philharmonic Society’s Music Award, the Yorkshire Post Book of the Year and the British Academy’s Derek Allen Prize. Volume two won the Whitbread Biography of the Year (1999), the Royal Philharmonic Society’s Music Award (1999) and the Samuel Johnson Prize for non-fiction (2000). It is also important to note that, unlike Barzun’s earlier monumental work, Berlioz and the Romantic Century (1st ed. 1950, 3rd ed. 1969), Cairns’ biography of Berlioz was made available to the French-speaking public: a French translation of both volumes was published in Paris in 2002 under the title Hector Berlioz : La formation d’un artiste 1803-1832 and Hector Berlioz : Servitude et Grandeur 1832-1869.

In addition to these major publications, David Cairns has also contributed several articles and chapters in edited books, and has lectured widely on Berlioz on both sides of the Atlantic.

See also on this site by David Cairns:

Berlioz

and Colin Davis, Berlioz,

Master Musician: A book review, Berlioz:

a centenary retrospect,

Introducing

Benvenuto Cellini, Interview

with Sir Colin Davis, Putting

Hector’s house in order, A

Berlioz bicentenary speech

See also: David Cairns (ed.), Discovering Berlioz (Toccata Press, 2019)

![]()

These speeches were given at the ceremony to award the insignia of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres to David Cairns on Wednesday 13 November 2013; they are reproduced here in the order in which they were given.

We are most grateful to David Cairns for sending us the text of his speech, and to the French Embassy in London for sending us the text of His Excellency Bernard Emié’s speech, and for granting us permission to reproduce them on this page. All rights of reproduction reserved.

Ladies and gentlemen,

It’s a great joy to welcome you to the French Residence for a special celebration.

Cher David Cairns,

Like your friend Neil Stratford, you took on a towering figure in French culture and restored his prestige at a time when he was on the verge of being forgotten.

It’s fair to say that the modern Berlioz revival largely began in the UK. His finest successes, today in Parisian concert halls are due largely to the passion of British conductors: from the late lamented Colin Davis, who passed away a few months ago, to John Eliot Gardiner, Roger Norrington and Simon Rattle, to name but a few.

When we look closely at the story of this group of Berlioz champions, cher David Cairns, we find that you play a key role in it. Not least, you began Sir Colin Davis’s love affair with the composer’s music, and you are Chairman of the Berlioz Society, founded in 1952.

I want to say how profoundly grateful we are to you for enabling today’s music lovers to enjoy Berlioz.

Born in Essex in 1926, you were extremely sensitive to music and early on you became aware of the musician’s practical needs, the urge to join forces and bring orchestral scores to life.

So in 1950, you persuaded a 22-year-old clarinettist, Colin Davis, to put on a concert performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni with you in Oxford. The experience was decisive; a new ensemble was born, and you called it the Chelsea Opera Group…so called because you were living in Chelsea at the time.

This group – in which it seems you sang and played percussion – was a fantastic springboard for the greatest musicians, from Simon Rattle to Kiri Te Kanawa. Colin Davis was its first appointed conductor, performing Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust and Romeo and Juliet back in the 1960s.

Since then, the Chelsea Opera Group has continually staged concert performances of what are occasionally little known operas, contributing to the renaissance of works which have since entered the repertoire of the biggest opera houses.

Just over 30 years later, you formed another amateur orchestra with a group of friends, The Thorington Players, which you conduct. Many of your concerts are for charity.

Berlioz dominates these two ensembles’ repertoire. And indeed, over the years you have forged a steady dialogue with the French composer.

But you weren’t immediately won over by him.

In your early twenties, when your sister made you listen to a recording of the Fantastic Symphony, the music made absolutely no sense to you.

In 1957, however, Covent Garden produced The Trojans. Many people were overwhelmed by the music; there was talk of a modern Berlioz revival. Your interest was kindled. Your cousin played you an old 78 recording of The Childhood of Christ. This time you were charmed by – in your words – "the strange sweetness and the purity of the piece", and when you were lent what was to prove a decisive book, Berlioz’s Mémoires, you became captivated by his personality.

In the 1960s, you set to work on your English translation of Berlioz’s memoirs. The critics were unanimous: your translation was the first to do full justice to the original.

While some people might sit back after such a success, for you it was only the start of a long love of Berlioz. You became the figurehead of the famous "Berlioz revival" in the UK.

Convinced that there were still documents to be explored, you contacted Berlioz’s descendants and unearthed a treasure trove of unpublished correspondence and other texts. You’ve said that you owe Yvonne Reboul-Berlioz a profound debt of gratitude for trusting you enough to let you turn her apartment in the Rue du Ranelagh upside down.

In 1989, the public became acquainted with the fruit of 20 years of research, a labour of love: you published the first volume of your almost 1,600-page-long summa: Berlioz’s biography.

This first part painted an unknown portrait of Berlioz: that of the provincial boy, son of the village physician, struggling to move to Paris and make a name for himself on the Parisian scene and distracted by his romantic impulses.

It won many prizes.

Ten years later, you published the second volume, to equal acclaim.

You devoted it to the genesis of his greatest works, starting with his masterpiece, The Trojans, and recount his friendship with Mendelssohn, Liszt and Wagner. You ended with a man crushed by personal tragedy and haunted by the fear of his music being forgotten after his death.

Critics are unanimous in saying that this landmark book in classical music history will be difficult to surpass.

Cher David Cairns,

Berlioz was a musician, conductor, author and eminent journalist for the Journal des Débats… Basically you’re like him: you’ve got many strings to your bow.

You’ve written for The Evening Standard, The Financial Times and The New Statesman, and were chief music critic of the Sunday Times in the eighties, having also been music critic and arts editor of The Spectator.

Your witty, keen analysis is a delight for your readers and your students both in the United States and at Merton College, Oxford.

And you continue to carry the torch: this very evening sees Romeo and Juliet at the Barbican, part of a special Berlioz cycle which has been on through November, and for which you took to the stage only last Wednesday to talk about Berlioz and the Romantic orchestra.

Cher David Cairns,

Berlioz apparently wanted to live 140 years to see whether his music would finally stir interest. Thanks to you, the job has been done. You have our gratitude for this.

David Cairns, au nom du Ministre de la Culture et de la Communication, nous vous faisons Commandeur dans l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

* * *

[in the original French]

Excellence, amis, collègues, parents, comment exprimer ce que j’éprouve en recevant cet honneur? Il me réjouit le coeur, et cela pour trois raisons en particulier. D’abord, à cause de ce grade de Commandeur. Lorsque, il y a une trentaine d’années, on m’a nommé Chevalier, je fus on ne peut plus ravi. En revanche, quand plus tard j’ai été élevé au grade d’Officier, je n’ai pu m’empêcher quand même de me sentir un tout petit peu déçu, “Officier” me paraissant sensiblement moins romantique que “Chevalier”, don’t j’avais été si fier. Cependant, cette fois-ci, aucune déception. “Commandeur” – cela surpasse tout. I remember the glee with which Colin Davis told me that an Italian society had made him “Commendatore”. (Apologies for saying this in English – I don’t know the French word for “glee”.)

Deuxièment, cet honneur me fournit l’occasion d’inscrire mes remerciements à ceux à qui je suis redevable de tant de gentillesses prodiguées dans le courant des années où je poursuivais mes recherches berlioziennes, surtout en France. Pour ne mentionner que quelques-uns: Catherine Vercier et sa mère Madame Yvonne Reboul-Berlioz, dans l’appartement de qui j’ai passé des semaines passionnantes à fouiller et transcrire un tas de documents familiaux inédits, et où l’idée du livre que je devrais consacrer à leur aieul s’est mise à prendre forme. Puis ces vaillants esprits qui ont fait du Musée Berlioz et du Festival Berlioz, à La Côte St André, quelque chose de vraiment digne du grand artiste qui y vit le jour; ensuite des musicologues, tels Jean-Pierre Bartoli, Rémy Stricker, Pierre Citron, Catherine Massip, Cécile Reynaud, qui, enfin, ont su établir le vrai génie et la grandeur de leur compatriote, pour l’honneur jusque là quelque peu terni de la France. Et, finalement, mes éditeurs, dont la rigueur, l’intelligence et la sympathie m’ont tellement profité, en Angleterre et en France: Tom Rosenthal, Diana Athill, Stuart Proffitt, Jean Vincent Richard, Sophie Debouverie, Dennis Collins. Mais n’oublions pas aussi ma pauvre famille, qui a dû vivre avec Berlioz pendant des années sans fin.

Troisièment et dernièrement, ce qui m’enchante le plus, c’est que cette décoration me provient de la France – ce cher pays qui est devenu (nonobstant mon français douteux) une seconde patrie pour moi ainsi que pour ma femme, et où nous avons pu, nous deux, partager cet amour commun pour elle pendant des heures sans nombre et inoubliables passées à Paris et en province. C’est surtout pour cette raison que je vous prie, Excellence, d’accepter ma sincère et profonde reconnaissance, et que je termine en vous invitant tous à porter ce toast: “Vive la France!”

David Cairns

![]()

We are most grateful to David Cairns for lending us a selection of his photos and for granting us permission to scan and reproduce them on this page. © David Cairns. Other photos and pictures have been taken or scanned from concert programmes and other publications in our own collection. All rights of reproduction are reserved.

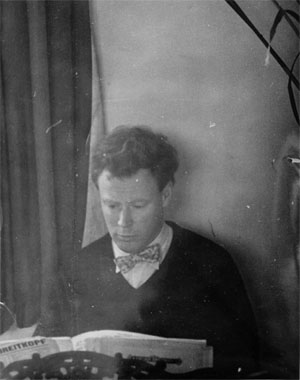

Davis Cairns is playing Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 5.

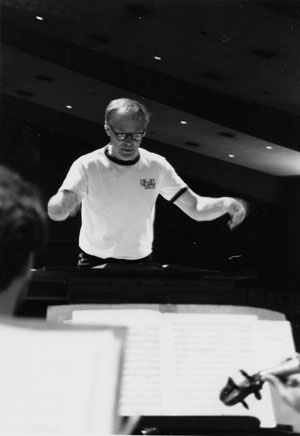

David Cairns is rehearsing the university orchestra (UCDSO) in Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony.

The above photo shows David Cairns at the Chelsea Opera Group 50th anniversary reunion.

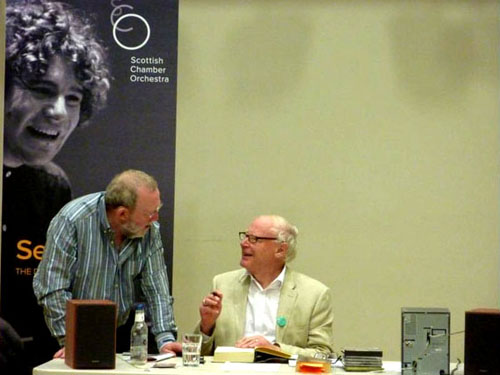

© Scottish Chamber Orchestra

This photograph was taken at the Berlioz Study Day organised by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra; the event was held at the Usher Hall, Edinburgh on 31 January 2010. On the table is a copy of the New Berlioz Edition full score of L’Enfance du Christ. David Cairns led the study day in conversation with Robin Ticciati, who conducted the SCO in three performances of L’Enfance du Christ over the following days. The photographer was Lucy Lawe (Scottish Chamber Orchestra). We are most grateful to the Scottish Chamber Orchestra for granting us permission to reproduce the above photo on this page.

© Scottish Chamber Orchestra

© Scottish Chamber Orchestra

The above two photographs were taken at “Explore Berlioz - October 2011”, organised by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and held at the Scottish National Library in Edinburgh on 1 October 2011. We are most grateful to the Scottish Chamber Orchestra for granting us permission to reproduce these photo here.

The above two photos were taken by Monir Tayeb at a talk given by David Cairns in the auditorium of the Hector Berlioz Museum on 30 August 2012. The talk, entitled “Berlioz et les deux Italie”, was delivered in conjunction with the Festival Berlioz.

The following photo, also taken at the same event, is courtesy of the Hector Berlioz Museum. We are most grateful to the Museum for granting us permission to reproduce this photo on this page.

© Musée Hector Berlioz

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir

Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Page Berlioz: Pioneers and

Champions created on 15 March 2012; this page created on 15 March 2012,

enlarged on 8 December 2013 and 22 October 2014.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.