![]()

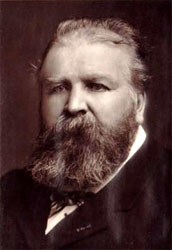

Conductors: Jules-Étienne Pasdeloup (1819-1887)

|

Conductors: Jules-Étienne Pasdeloup (1819-1887)

|

|

Introduction

Selected texts

Letters

Journals in Berlioz’s lifetime

Journals after Berlioz’s death

Table of performances

Illustrations

This page is also available in French

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.

![]()

The conductor Jules Pasdeloup (1819-1887) holds a very special place in the history of music-making in France in the period from the 1860s to the 1880s, and his influence extended widely outside the frontiers of his own country. Though eclipsed subsequently by younger and more talented rivals like Édouard Colonne and harles Lamoureux, both of whom had learned and benefited from his example, it was Pasdeloup who brought about a veritable revolution in the musical world through the creation in 1861 of his Concerts populaires in Paris. Large sections of the public, which hitherto had hardly been in a position to attend or indeed evev afford classical concerts, were introduced to serious classical music, and in the process the size of the concert-going public in Paris was considerably enlarged. Not only did Pasdeloup bring to large audiences the established classical repertoire – Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, Mendelssohn – but he extended his promotion of music to new works by contemporary composers without regard to their national origins. Young French composers benefited – Gounod, Saint-Saëns, Bizet and others – but also composers from abroad, and most strikingly Berlioz and Wagner, the two greatest but also the most contested composers of the day. The spectacular development of concert activity in Paris and France in the 1870s and 1880s is due to a large extent to his achievements, and, as Ernest Reyer and Adolphe Jullien both insisted, it is partly thanks to him that first Berlioz, then Wagner became accepted and admired in France.

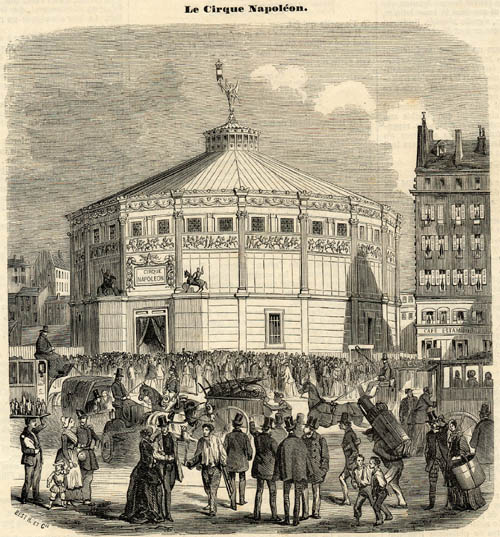

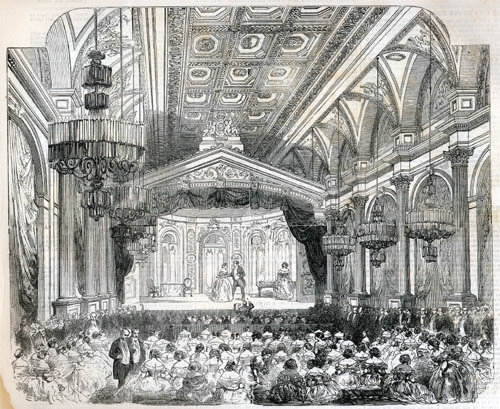

The son of a former conductor at the Théâtre Feydeau, Pasdeloup’s early years were difficult: his father died when he was 14. He studied at the Conservatoire where he won a first prize for piano at 15 and subsequently became a teacher there. His conducting career seems to have been initially prompted by his early composing ambitions: unable to secure from Habeneck a performance at the Conservatoire of one of his works, he formed an orchestral society recruited from students at the Conservatoire, the Société des jeunes artistes. It gave its first concert on 20 February 1853 and went on functioning for another nine years at the small Salle Herz in Paris. From the start, Pasdeloup performed works of the classical masters, and also those of young French composers like himself who had found it difficult to get a hearing (it should be said that Pasdeloup never used his position as conductor to promote his own music). Despite securing influential patronage the society eventually went bankrupt, and in 1861 Pasdeloup was forced to try a new formula: this led to the foundation of the Concerts populaires, for which he selected a new venue, the vast Cirque Napoléon (renamed after the overthrow of Napoleon III in 1870 the Cirque d’Hiver) which could seat an audience of 5,000, far more than any other hall in Paris (for comparison, the Conservatoire could only admit fewer than 1,200). What is more, the price of the tickets was kept deliberately low. At a stroke classical music could now reach a much larger audience than ever before in Paris. The venture, which at first was a gamble, turned out to be an astounding success, and contemporary sources, including Berlioz himself, attest to the very special atmosphere and excitement which attended this bold initiative in bringing classical music to the masses. The Concerts populaires became an institution, which was soon widely imitated in other cities in France. Success lasted well over a decade and survived the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1 (Pasdeloup’s conduct at the time won him credit), but from 1873 onwards there was increasing competition, first from Édouard Colonne, then from the early 1880s from Charles Lamoureux. Eventually Pasdeloup decided to retire at the end of the 1883-4 season, only to return again in October 1886 with a new series of concerts, the first of which celebrated the 25th anniversary of the foundation of the Concerts populaires. But by then Pasdeloup was a broken man and he died in August of the following year.

Pasdeloup was neither a great conductor nor a great musician, as ungrateful critics like Saint-Saëns emphasised, and even sympathetic writers like Ernest Reyer and Adolphe Jullien conceded the point. Privately Berlioz had a low opinion of his conducting abilities, which did not match Berlioz’s own very exacting standards. It can be said that Pasdeloup achieved his success not thanks to his musical abilities but in spite of them. As a person he was reportedly gruff, self-assured, opinionated and not receptive to advice; he could be particularly brusque with composers who ventured to offer their advice at rehearsals. But his love of music was total, and to that he sacrificed everything: far from enriching himself through his concert activities he lost a great deal of money, and in financial matters behaved with scrupulous integrity. He had boundless energy, infectious enthusiasm and above all a sense of mission, and developed a very special rapport with his audience. The founder of the Concerts populaires was anything but a populist, and he would not pander to public taste. He was determined to secure a hearing for music whose value he believed in, and to this end he was prepared to stand up to hostile audiences until they eventually came round to his way of thinking (one illustration is during the first performance he gave at his concerts in 1874 of the prelude to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde). In this way many a composer and many a work which large sections of the general public had initially regarded with suspicion eventually became accepted. In short, in Adolphe Jullien’s words, Pasdeloup was ‘the great musical educator’ of France.

Among conductors who championed the music of Berlioz Pasdeloup is in a unique position: not only did he know Berlioz personally and heard him conduct, he even performed music by Berlioz in the presence of the composer. Berlioz must have known Pasdeloup for some time before he first mentions him in his writings in 1853: Pasdeloup had been a timpanist in the short-lived Société Philharmonique of 1850-1851 (CG no. 2077). Berlioz’s views of Pasdeloup are on record in a number of his writings (all the most important passages are reproduced in translation on this page), but a distinction must be drawn between his public pronouncements – in his feuilletons in the Journal des Débats between 1853 and 1862 – and his private comments in his correspondence between 1855 and 1868. The difference between the two is often striking and they should be considered separately.

In his public statements Berlioz expresses himself positively for the most part. Pasdeloup’s general aims could have struck a chord with Berlioz himself. In 1853 Berlioz welcomes the foundation of the Société des jeunes artistes, and in 1857 gives a striking – and accurate – characterisation of Pasdeloup as an energetic and enterprising ‘musical condottiere’, whose willingness to take initiatives deserved praise, flawed though the execution may sometimes have been. He commends him for bringing for the first time to the Paris public the first part of Mendelssohn’s Elijah and despite reservations the performance as a whole receives praise. In 1858 and 1859 Berlioz notes the improvement in the standard of orchestral playing (in connection with a performance of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony) and acknowledges the services the society has already rendered to the art of music. When it came to the foundation of the Concerts populaires in October 1861 Berlioz was impressed as were many contemporaries by the imaginative boldness of the undertaking, and he does justice to its significance. He gives a striking description of the atmosphere in the vast Cirque Napoléon and the hushed excitement of a crowd that had hitherto been starved of classical music. He reviewed two subsequent concerts, in January and November 1862, and though pointing out in the first review a flaw in the performance of one piece, he commends in the second review the playing by the orchestra of two works by Beethoven.

The composer’s letters tell a much less flattering story. He jokes about Pasdeloup to his friends (CG no. 2071), regards him as an upstart directing a less than first-rate orchestra (CG no. 2077), objects to the way Pasdeloup’s concerts in the 1850s have made it more difficult for him to give concerts himself (CG nos. 2077, 2216), and is especially anxious to prevent Pasdeloup conducting his own music (CG no. 1930). He is displeased at Pasdeloup’s cavalier manner with composers: Pasdeloup curtailed on two occasions the ending of Weber’s Invitation to the Dance in Berlioz’s orchestration, without warning him (CG nos. 2581, 3072), and was prepared to perform an orchestral excerpt from La Fuite en Égypte against the composer’s wishes (CG nos. 3122, 3124). Berlioz’s last two references to Pasdeloup are scathing: Pasdeloup ‘massacres’ his music, and Berlioz is glad he is not attending a performance of an excerpt from Roméo (CG nos. 3241, 3346).

But even that is not the whole story. When writing to his publisher early in 1864 Berlioz evidently regarded the Pasdeloup concerts as suitable for the performance of the orchestral Trojan March he was composing (CG no. 2827). Two of the performances given by Pasdeloup were attended by Berlioz, that of the Francs-Juges overture on 22 January 1865 and that of the Septet from Les Troyens on 7 March 1866. In both cases, particularly the second one, Berlioz was deeply moved by the occasion and the warmth of the public response, and he writes at length about them (CG nos. 2970, 2978 for the overture; CG nos. 3110, 3115, 3117 for the Septet). On both occasions Berlioz implies that he was satisfied with the performance, and in the second one he comments appreciatively on the ‘large and excellent orchestra’. This latter performance was Berlioz’s last major concert success in Paris – those still to come were all abroad – and one cannot but wonder whether, had he attended any of Pasdeloup’s performances of his music in 1868, his presence in the hall might have galvanised the audience to respond as they had done on those earlier occasions. At any rate, Pasdeloup’s promotion of his music in the 1860s and after helped to lay the foundations for the Berlioz revival of the 1870s, though Berlioz at the time could not have been aware of that.

It is very likely that Pasdeloup will have seen and heard Berlioz conduct in Paris on numerous occasions, including the large-scale concerts Berlioz gave in 1844 and 1845. It can be assumed that he admired the music of Berlioz: it was his normal practice only to play music that he himself believed in. He was not a champion of any single composer and did not have a speciality, unlike his rivals Colonne and Lamoureux, but rather wanted to bring to a wider public all serious music he judged worthy of performance, whether past or contemporary, and irrespective of fashion and nationality. He pursued this goal to the end of his career: in his last season he devoted a concert to the music of César Franck, and invited Franck to conduct at this concert (30 January 1887; Le Ménestrel 6/2/1887, p. 79). His lack of specialisation may have been both a strength and a weakness: he performed a great deal of music, but his coverage of any particular composer was necessarily selective, and the standards of performance could also be variable.

His record with the music of Berlioz, summarised in the table below, illustrates this (the same analysis could be applied to his performances of Wagner). In his very first concert with the Société des jeunes artistes on 20 February 1853 he included a work by Berlioz, the Carnaval romain overture, which later became a regular item in his repertoire (Berlioz was present at the performance, but it is not known what he thought of it). Eight years later, after the foundation of the Concerts populaires in 1861, he returned to Berlioz, first with the orchestration of Weber’s Invitation to the Dance (a regular favourite with audiences in the 1870s and 1880s, though probably with the omission of the concluding andante that Berlioz complained about), then with the Carnaval romain overture. From then onwards till he retired in 1884 he made a point of performing every year at least one piece by Berlioz (and often more than one), and this remained true of his final season in 1886-1887. Analysis of his programming of Berlioz suggests he was following a conscious method: to carry his audience with him he would begin by playing single pieces or a single excerpt from a larger work. He would then progress to longer excerpts, and eventually to the complete work. This progression can be observed with his performances of music from the Damnation of Faust, from the single Marche hongroise in 1868 to the complete work in 1877, on the same day as Colonne. The same pattern can be seen with his treatment of Roméo et Juliette from 1868 onwards, though here Colonne got ahead of him with a complete performance in December 1875, and it was not till three years later that Pasdeloup was able to match this. The first two symphonies show a different pattern. Pasdeloup was the first conductor after the death of Berlioz to attempt the complete Symphonie fantastique in 1873 (though according to Adolphe Jullien he omitted on this occasion the last movement); the work was at first coolly received, so he performed just one movement later in the year. The work was eventually accepted by the audience and became a staple of his repertoire from 1876 onwards (it was the last work by Berlioz he conducted at his last Concert populaire on 27 March 1887). He was the first also to perform the complete Harold in Italy in 1876, and it was a success from the start. By this date the competition from Colonne was becoming intense, and his response was to put on a complete concert performance of La Prise de Troie in 1879, which had never been performed anywhere. Colonne in turn was forced to respond by following his example, and though initially outpaced by his rival, he eventually was more successful than Pasdeloup. As far as the music of Berlioz was concerned, Pasdeloup was by now losing the battle, and though he continued to give numerous performances after this time he did not introduce any new titles to his Berlioz repertoire. But his public support for Berlioz continued to the end: he was present at the inauguration of the Berlioz monument in Montmartre on 8 March 1887 (Le Ménestrel 13/3/1887, p. 117).

As a conductor of Berlioz Pasdeloup was capable of delivering performances that were judged to be good even by friends of Berlioz who had heard the composer conducting his own works (see for example Ernest Reyer’s review of Harold en Italie in 1876), but reading between the lines it is not difficult to detect reservations (for example in Auguste Morel’s review of a complete Damnation in 1878). One reviewer in 1881 contrasted Pasdeloup’s conducting of the Damnation with that of Colonne, to Pasdeloup’s disadvantage. A comparison of Pasdeloup’s Berlioz repertoire with that of Colonne for the period down to 1884 is also instructive. Once Colonne had defined his role as a Berlioz specialist, he went off the beaten track to include works that his rival had not attempted; as well as other shorter pieces this included the overtures to Benvenuto Cellini and le Corsaire, Tristia, the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale, the complete Enfance du Christ, the Requiem, and even Lélio (though without the spoken role).

For all his faults, Pasdeloup made an immense contribution to the musical scene of his time. Writing in 1890, when Colonne and Lamoureux had long established themselves, Adolphe Jullien stated that Pasdeloup was the most popular conductor there had ever been in France. An article by Félix Jahyer in 1880, at a time when Pasdeloup’s enterprise was already under threat, made a plea for him to receive state support. When in 1884 Pasdeloup announced that he was retiring, the news was greeted with dismay by sympathetic critics (see the comments of Ernest Reyer, Arthur Pougin, and Adolphe Jullien), and his death in 1887 evoked warm tributes at the time and for years afterwards (see again Arthur Pougin, Ernest Reyer and Adolphe Jullien).

![]()

The texts are grouped into three sections: (1) Letters, all by Berlioz unless otherwise indicated (2) Journals dating from the composer’s lifetime (down to 1862 the articles are by Berlioz himself unless otherwise stated) (3) Journals dating from the time after his death.

References are all to Correspondance Générale (abbreviated CG)

To Gaetano Belloni [Liszt’s agent] (CG no. 1930; 28 March, from Brussels):

I would be most obliged to you if you would go straightaway to see Pasdeloup and beg him very forcefully on my behalf not to perform my overture Le Corsaire at his concert next Sunday [1st April]. His orchestra is not up to it, and I have not yet been able to perform this overture in France. You can imagine that I am anything but pleased to let it receive a first performance of this kind. […]

To Toussaint Bennet, Théodore Ritter and the Chevillard quartet (CG no. 2071; 23 December, from Paris):

[…] You know that Girard has just been named Senator; ‘Pas de loup’ [= ‘wolf’s step’] is running around to secure his baton (Girard’s baton) at the Imperial Academy of Music [the Opéra]. He will get it, until he himself is admitted soon to the Senate, in which case it would not be proper for him to exercise rhythmical functions in a theatre. That would be a pity, and I hope that ‘Pas de loup’ will not become Senator. The interests of art come first.

He directed a concert at court recently in a room next to where audiences were being held; the door of the music room was open. ‘Pas de loup’ starts a symphony, the Emperor walks in, and on hearing the noise quickly asks for the door to be shut. […]

To Auguste Morel (CG no. 2077; 9 January, from Paris):

[…] I cannot attempt anything of any importance in Paris, there are obstacles in everything and everywhere. No hall, no performers (of the kind I would like). There is not even a Sunday free which I could use to give my little concert. Some are taken up by the Société des concerts [the Conservatoire], others by the Société Pasdeloup [the Société des Jeunes Artistes], which has booked Salle Herz for the entire season.

I have to make do with a Friday. Pasdeloup is our former timpanist who has posed as a conductor. He has collected under his orders a band of young lads from the Conservatoire, and by dint of wriggling around he has managed to secure the patronage of M. de Nieuwerkerke and Princess Mathilde, to conduct the concerts of the Hôtel de Ville, and will end up by being Master of the Emperor’s Chapel (just wait and see). Apart from the young Bennet, Théodore Ritter, who is a wonderful child in whose future I sincerely believe, Camille Saint-Saëns, another great musician who is 19, and Gounod who has just written a very fine Mass, of all that is flitting over the stinking swamp that is called Paris I see nothing that is not ephemeral. […]

To Princess Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein (CG no. 2216; 18 March, from Paris):

[…] I see so many hideous absurdities being produced and bandied about in our musical world that every day my desire to withdraw from the fray increases. Nevertheless I did feel like giving here a grand performance of Faust which the Parisians hardly know at all; I was not able to find either a hall or any singers. Forget about it. Since the little society of students of the Conservatoire was formed under Pasdeloup’s comical direction and under the patronage of Princess Mathilde, any large-scale concert has become almost impossible in Paris during the musical season. […]

On the letter CG no. 2580 to Auguste de Gasperini, see the note below on CG no. 3072

To his niece Joséphine Suat (CG no. 2581; 27 November, from Paris):

[…] As for the piece you mention and which was encored by the audience of 5000 which filled the Cirque Napoléon, I am not responsible for the cut which a critic so wittily reproached me with. I have indeed orchestrated the piece by Weber but in its entirety; it is the conductor who, without warning me, omitted the short concluding andante, so as not to prevent applause. […]

To Stephen de la Madelaine (CG no. 2582; 1 December, from Paris):

[…] You cite a paper, the Réforme musicale. This paper asserts that at the Pasdeloup concert the Invitation to the Dance cut a very sorry figure, when on the contrary this piece was encored by an audience of more than 4000 and encored amidst enthusiastic applause. I have no doubt that you were unaware of this fact; but why should you give credence so easily to the assertions of a paper which attacks me because, together with many others, I have been unable to endorse the usefulness of the Chevé method? […]

[On Berlioz and the Chevé method see Journal des Débats 19 February 1861]

To the publisher Antoine Choudens (CG no. 2827; 19 January, from Paris):

[…] I have also started orchestrating and developing the Trojan March for concert performance; I believe it will make a splendid piece which could be played with great effect at the Conservatoire, at the Pasdeloup concerts, at those of Arban, everywhere. I am capable of giving a concert to have it performed, together with the Royal Hunt and Storm, played by an orchestra of the right calibre and conducted in my own way. […]

To Toussaint Bennet (CG no. 2843; 15 March, from Paris):

[…] Pasdeloup played a scene [the Septet] from Les Troyens at the last concert at the Hôtel de Ville and did not even notify me of the rehearsal. […]

To Estelle Fornier (CG no. 2970; 20 January, from Paris):

[…] The day after tomorrow there will be a performance, here in Paris at the Cirque Napoléon, by the vast orchestra of Pasdeloup, of my overture Les Francs-Juges. I was told that at the rehearsal the day before yesterday it had a tremendous success with the musicians. […]

To Estelle Fornier (CG no. 2978; 16 February, from Paris):

[…] I was telling you in my last letter that my overture Les Francs-Juges was going to be performed at the Cirque concert and that M. Gasperini was going to give a lecture on my score Les Troyens. In addition, M. Deschanel also gave a lecture in another hall on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet where he cited me because of my large choral symphony on this subject. Both speakers were warmly applauded. As for the overture, it provoked a virtual riot. After the last bar there was an eruption of applause, and after the third salvo my three faithful hecklers did not fail, as is their custom, to hiss vigorously twice. The applause then redoubled, and 4000 pairs of hands were clapping furiously, people were waving their handkerchiefs and hats. The spectacle in the Cirque was remarkable. At the exit I was stopped on the boulevard, people unknown to me came to shake my hand, ladies introduced themselves and complimented me. One of them told me: « What verve! and what orchestral know-how there is there; one can see that you have just written this work. — I regret to say, Madam, I answered, that this work was written thirty-seven years ago; it is my first piece of orchestral music. »

That is the Paris public; you find there people who know nothing about the art they profess to love. For them it is like writing on water, or at least on sand.

The aim of my three determined hecklers is not to carry with them the public after performances of my works, but only to make it possible for hostile papers to say: « At this place this particular piece by M. Berlioz was played, and the piece was heckled. » And that is true, and they have really achieved their objective with the readers of these papers. I will probably never know what has earned me this loyal hatred which has been on display for the last two years at the Opéra, at the Théâtre-Lyrique, at the Conservatoire, at the Cirque, everywhere.

I did not want to attend this concert, but the conductor had insisted so much on my presence that I could not refuse this to him. I had put aside to send you several papers which relate the incident, but I thought it childish to give in to this temptation. […]

To Auguste de Gasperini (CG no. 3072; 17 December, from Paris):

I have just read in Le Ménestrel [17 December 1865, pp. 19-20] your article on last week’s concerts and I was surprised to find this sentence: I will always regret that the Invitation to the Dance, orchestrated by Berlioz, stops before the andante which concludes this fine piece by Weber. I do not know whether Berlioz deliberately omitted this concluding section of the waltz for the sake of effect in performance, though I very much doubt it, etc.

Well you should not have DOUBTED; you are not one of those who can believe me capable of lacking in respect for a fine work and a great master, out of a childish concern for what is called in France and Italy effect. I orchestrated the piece by Weber as it is, without cutting out a single bar; the printed orchestral parts which are in use everywhere demonstrate this, and when I had the opportunity to perform under my direction this delightful fantasy which has so much character, in France, in England and in Germany, the concluding andante has never been omitted. […]

[Note: Pasdeloup had already performed the same work at a concert on 3 November 1861, also with the omission of the concluding andante. This emerges from the letter CG no. 2581 cited above, which also shows that an unnamed critic had pointed this out. The above letter to Gasperini is reproduced with identical wording in CG as no. 2580 and assigned the date 10 November 1861, but it is highly implausible that Berlioz should have written an identical letter at five years’ interval; this seems to be a doublet of CG no. 3072, the date of which is firmly anchored to 17 December 1865 through its publication a week later in Le Ménestrel of 24/12/1865, pp. 27-28, as well as by the article of Gasperini published on 17 December]

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 3110; 8 March, from Paris):

[…] I wanted to tell you about what happened yesterday at a grand special concert, with trebled ticket prices, at the Cirque Napoléon and for the benefit of a charitable society, under the direction of Pasdeloup.

The Septet from Les Troyens was being performed there for the first time. Mme Charton was singing; there were 150 choristers and the usual large and excellent orchestra. Except for the march from Lohengrin by Wagner, the whole of the programme was very badly received by the public. – The overture to Le Prophète by Meyerbeer was furiously hissed; the police intervened to expel the hecklers…… Finally came the Septet. Immense applause; shouts of bis. The second time round the performance was better. I was spotted on my bench, where I had climbed for my three francs (I had not been sent a single ticket); then renewed shouting, curtain calls, waving of hats and handkerchiefs: « Long live B…! stand up! we want to see you! » And I was trying to hide as best as possible! At the exit on the boulevard I was surrounded. This morning I had visits, and a charming letter from Legouvé’s daughter. Liszt had come, I spotted him from the top of my platform; he has arrived from Rome and did not know any of Les Troyens. Why were you not there? There were at least 3000 people. In the past this would have been a source of great joy…

The effect was grand, in particular the passage with the sounds of the sea, which the piano cannot reproduce,

« Et la mer endormie

Murmure en sommeillant les accords les plus doux. »

It moved me deeply. My neighbours in the circle, who did not know me, shook my hands and expressed all sorts of thanks when they learned that I was the author of the piece… Remarkable. If only you had been there!….. It is sad, but it is beautiful!Regina gravi jamdudum saucia cura. […]

[The last line is a citation from the start of Book IV of Virgil’s Aeneid]

Auguste Morel to Berlioz (CG no. 3115; 13 March, from Marseille)

To Auguste Morel (CG no. 3117; 15 March, from Paris)

To Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 3122; 22 March, from Paris):

[…] On Easter Sunday [1st April] the three pieces from La Fuite en Égypte will be performed at the Conservatoire. Meanwhile my idiot of Pasdeloup announces for next Sunday [25 March] the overture to La Fuite en Égypte, in other words the little orchestral piece during which the shepherds are supposed to be gathering at the manger in Bethlehem. I have just written to him to beg him not to do this, but I bet he will persist. This is absurd, as the piece cannot be separated from the chorus which follows. […]

Jules Pasdeloup to Berlioz (CG no. 3124; 25 March, from Paris):

It is only after careful thought that I arrange my programmes; the best answer I could make to your letter is to have performed your music today. The overture to La Fuite en Égypte is a connoisseur’s piece, and I now have enough trust in my public not to be afraid of taking certain risks.

The overture had a deserved success and if there had not been shouts of Bis there would not have been the slightest protest. So please feel satisfied since I am myself. […]

To Auguste Morel (CG no. 3241; 12 May, from Paris):

[…] Some time ago Roméo et Juliette was performed at Basel in Switzerland; de Bülow was directing the director. Mme de Bülow wrote to me about this. The day before yesterday there was a performance of L’Enfance du Christ in Copenhagen, which was performed a month before in Switzerland. My music is now performed almost everywhere, even in America, though not in Paris. And yet here Pasdeloup massacres some of my pieces from time to time. […]

To Vladimir Stasov (CG no. 3346; 1 March, from Paris):

[…] P.S. At this moment that brute of Pasdeloup is performing at his concert the Festivities from Roméo et Juliette, and God knows how this is going… I am in bed and I am lucky not to be hearing this. […]

![]()

Abbreviations: Débats = Journal des Débats; Ménestrel = Le Ménestrel

Débats 17 March, p. 3 […] I must conclude by adding that a new musical association has just been formed, undeterred by the two existing ones, which brings to three the number of Societies of this kind […] It has been established by bringing together young artists under the talented direction of M. Pasdeloup, and aims in particular at giving performances of the works of young composers and at practicing in public the techniques of musical performance. These students who include, it must be said, a number of professors, have made a brilliant start by performing with ensemble Beethoven’s first symphony in C major and a fine large overture by M. Lacombe. […].

Débats 14 December, p. 2 […] M. Pasdeloup, the director and conductor of the Société des jeunes artistes, belongs to that class of musical condottieri who though unconventional are very much alive; they are energetic, active and in the final analysis actually do something. Now I do not share the opinion of those who think that it is better to do nothing than to do something imperfectly. If this was the prevailing opinion in the world of arts, sciences and industry, we would now have neither photography, nor railways, nor steamboats, nor electric telegraphy, nor a dozen other wonderful achievements of the human spirit which at first were very far from resembling what they are now. […] To succeed in doing something well, it seems to me obvious that you have to start by doing it somehow. As far as music is concerned, this may involve massacring a few masterpieces here and there, but there are masterpieces that are able to recover from their wounds, and which after all owe it to their honest assassins that they later become known and appreciated. But let us try to commit as few murders as possible.

A few years ago this might have applied to M. Pasdeloup, but it is no longer true today. Recently he decided to do something, to perform a great work that is unknown to the Parisians, Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and he has succeeded. He has given a performance of at least the first part of the work. This meant finding a large hall; he secured the Cirque, and then had to remedy its dreadful acoustic by preventing the waves of sound from rolling around; he had to find by trial and error the only way of setting out the orchestra and chorus that would achieve this end. M. Pasdeloup had a stage constructed for the orchestra and a reflector placed behind the last few rows of choristers, who are spread around on tiers behind the orchestra, and the Cirque is now the best venue I know for large-scale concerts. Even Exeter Hall in London cannot stand comparison with it.

Admittedly this cost a great deal of money, but the takings for the Mendelssohn festival have more or less covered the expense involved in setting in motion this large musical machine. One must applaud the upsurge of curiosity which last Sunday [6 December] drove large crowds to the Cirque in the Champs-Elysées. The spectacle of this large audience and this mass of performers, so ingeniously arranged, was magnificent to behold. In addition the performance was almost flawless. In the arias and duets of Elijah, the orchestra often accompanied far too loud, an inevitable drawback with such a large instrumental body if the whole body of strings is allowed to play instead of being reduced to a small orchestra for the accompaniment. But the wind instruments were faultless, and the effect of the voices in these grand choral ensembles struck the entire audience with its majesty. […]

Débats 6 January, p. 2 […] The Société des Jeunes Artistes, conducted by M. Pasdeloup, has just resumed its series of concerts in Salle Herz. The first was very fine and there was a noticeable improvement in the standard of orchestral playing. The dramatic overture to Struensee by Meyerbeer, which M. Arban had already performed a few days earlier at the Concerts Parisiens, was full of dangers for M. Pasdeloup’s young orchestra. It is a difficult piece, especially for the violins. All the same they performed it without a hitch and with much fire and precision. […] M. Pasdeloup’s orchestra also played very well the symphony in E flat by M. Gounod, an excellent work, the andante of which in particular made the greatest impression. […]

Débats 5 March, p. 1 […] The other institution [apart from the Conservatoire], the Société des Jeunes Artistes, which M. Pasdeloup directs with zeal and dedication, does not have a venue of its own. Its sessions take place in Salle Herz, rue de la Victoire, for which it pays rent, and where there is hardly space for an orchestra of sixty musicians and a chorus of some forty voices. The Society is even unable to hold in this hall the small number of rehearsals indispensable for every concert, and for its preliminary studies it is obliged to make use of another one. The musicians associated with the venture make very little money out of the six or seven annual sessions; they are obliged to make a living by using their skills elsewhere in many different ways, and as a result they are rarely punctual at rehearsals. It hardly ever happens that at these preliminary session the orchestra is at full strength. […] Frankly, you cannot blame them. But what torment for the director and conductor of the Society, and what torment for the composer, if he is present! He can indeed attend, as the Society, while showing respect from the famous dead, has not declared war on the living. Far from it, it must be acknowledged that with its limited means it has already performed important services for modern art. […]

Débats 18 February, p. 3 […] One honourable exception must nevertheless be made in favour of virtuoso players of a certain standing; the majority of them, when they wish to give a concert, turn to the orchestra of the Société des Jeunes Artistes, which M. Pasdeloup directs. This band of instrumentalists counts in its ranks some players of real talent and thoroughly deserves to be called an orchestra. At their first matinée this year, the young musicians have even given a performance of Beethoven’s Pastoral symphony that was remarkable and worthy of praise. How the poems of antiquity, however beautiful and admired they may be, pale in comparison with this marvel of modern music! […]

Ménestrel 10 November, p. 399 (anonymous review): […] The great success of the evening went to Weber’s Invitation to the Dance, orchestrated by Berlioz. This masterpiece was thrown off with most remarkable vigour and ensemble, and was unanimously encored. […]

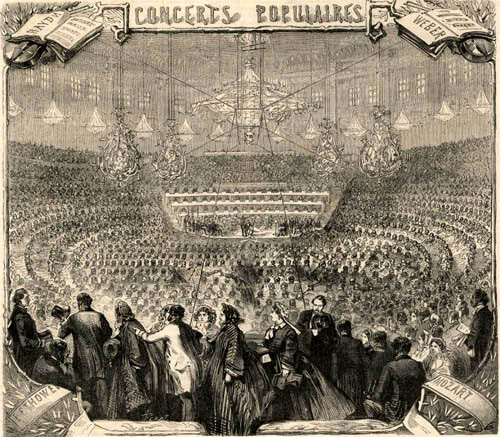

Débats 12 November, p. 2 […] M. Pasdeloup has just had a bold idea, the improbable success of which has exceeded all his hopes. He wanted to know what effect the works of masters would have on a largely uncultured audience such as that which frequents the theatres of the boulevards. For this purpose he hired at his own risk and expense the Cirque-Napoléon, where a platform was built that could hold some 100 musicians, and every Sunday at two o’clock he gives popular concerts at a low price, where the masterpieces of Beethoven, Mozart, Weber, and Mendelssohn are exclusively performed, in short great instrumental music of stature. The crowds have flocked there with eagerness and even passion, and without witnessing this oneself it is hard to imagine the rapture with which this audience of four or five thousand listens to overtures and symphonies. They may not, it is true, appreciate them at their true worth, but the elevation of ideas and forms of this music strikes them with wonder and moves them to intense excitement.

There is a hushed and awestruck silence around the numerous tiers arranged in a circle and full up to the last row. Occasionally a huge gasp, quickly contained, breaks out when in certain passages the musical emotion becomes too intense. But they never interrupt, and all wait till the last note has sounded; only then do acclamations and applause break out with a sincerity and energy hardly known in our theatres and concert halls. And so in two sessions M. Pasdeloup has enabled nearly ten thousand people to enjoy the Pastoral Symphony and the Symphony in C minor by Beethoven, the overture to The Magic Flute by Mozart, Weber’s Invitation to the Dance and several wonderful pieces, the existence of which this public did not suspect, still less their striking charm. I will not attempt to describe the acclamations and furore which greeted Alard after Mendelssohn’s violin concerto, and Jacquart after that of Molique. Nowhere have the two virtuosi been so warmly welcomed. Already the elegant public is streaming towards the Cirque-Napoléon, attracted possibly by the concerts themselves but also by the novelty of the spectacle. M. Pasdeloup has the joy and the credit of having founded a fine institution which we lacked; he has won the battle. […]

Débats 28 January, p. 1 […] The Concerts populaires of the Cirque Napoléon continue to attract an immense crowd, though in truth they are now popular only in name. Smocks have disappeared, and all you can see is black tails and elegant evening dresses. High society too is fond of inexpensive music. The main reason, the true reason why every Sunday some four or five thousand music-lovers flock to the Boulevard des Filles-du-Calvaire, is that there it is possible to hear for 75 centimes masterpieces of symphonic art. The concert before last [19 January] had a programme which did not satisfy the audience entirely in all its parts. The overture to Médée [by Cherubini] made little impact. On the other had every movement of Beethoven’s symphony [no. 2] in D provoked a storm of applause. The enthusiasm of this immense crowd seemed unable to exhaust itself; when one side of the Cirque had finished applauding, the other would start again. […]

The excerpts from Haydn’s symphony [no. 52] seemed rather colourless side by side with Beethoven’s great work, and the overture by Ries, with its bombast, accumulation of aimless modulations and its rather vulgar material, did not find favour with most of the audience who felt impelled to show their displeasure. Besides, the trumpets were out of tune with the rest of the orchestra, and the sharp pitch of their high notes was a veritable torment for sensitive ears. We draw the attention of M. Pasdeloup to this point. […]

Débats 19 November, p. 1 […] It is this overture [Beethoven’s Coriolanus] which M. Pasdeloup performed last Sunday [16 November]. Nevertheless the Paris public grasped that it is a beautiful work, seeing that the vast circular amphitheatre resounded with fairly respectable applause after the final chord of the masterpiece. But all the excitement of the audience and its enthusiastic shouts of bis were for the pretty rigaudon from Rameau’s Dardanus, and for the finale of a Haydn symphony [no. 29]. The overture had nevertheless been well played at the correct tempo, with all the required fire and vehemence. […]

At the same concert Beethoven’s piano concerto in E flat [no. 5] was heard, performed by M. Jaell with breadth, simplicity and warmth, free from rhythmic slackness and with an energy that was always devoid of brutality. M. Jaell is a great pianist and a distinguished musician. This we knew, but he gave there a new and resounding proof of the fact. His success was total; he was acclaimed and called back several times. In this vast concerto-symphony too the orchestra was beyond reproach. […]

[Note: the review in Le Ménestrel 23/11/1862 p. 415 (by J. Lovy) agrees closely with the verdict of Berlioz on the reaction of the audience]

Ménestrel 22 January, p. 70 (anonymous review): — At the last matinée of the Concerts populaires, there was a degree of resistance to the overture Les Francs-Juges by Berlioz; but in truth it should be noted that through its applause the vast majority of the public declared itself in favour of this work. All that was needed to win over the doubters was probably a better knowledge of the subject that had inspired the composer.

Ménestrel 25 February, p. 100 (A. de Gasperini): […] In the meantime M. Pasdeloup forges ahead. He searches, he invents, he takes risks. If told that he is going to be met with hisses, he keeps going; if told that the public will get tired of following him, he goes faster and higher. Now it sometimes happens that the public comes over to his side, supports and urges him on. In the applause which greets every new act of daring, a large part and the warmest is for the conductor himself, his persistence in opening up broader ways and shaking off the shackles of routine. […]

Ménestrel 11 March, p. 117 (A. de Gasperini): […] Last Wednesday [7 March] M. Pasdeloup gave at the Cirque Napoléon a large concert for the benefit of the Œuvre des

Faubourgs. This concert, the programme of which included the names of the

leading masters of the time, had attracted an enormous audience. I would like to write about it at length, but space is limited and I will only mention two

moments which have their value.

The overture to Le Prophète had just been performed,

a piece about which one may no doubt argue but which shows at every step the

hand of the master. Someone or other felt he had to protest against the applause of the hall with a cat-call.

There was general indignation, shouting, uproar and

screaming. « Meyerbeer should not be hissed! » shouted one of the

audience, and the heckler was about to get rough treatment.

The police arrived, the individual was arrested and was about to be led away in the corridor, when M. Pasdeloup came forward to the edge of the platform amidst a dreadful din and said: « Gentlemen! opinion is free! ». He was furiously applauded, and I imagine the heckler was allowed to come back into the hall.

The superb Septet from Les Troyens was encored. It is hard to imagine the effect of this piece on an impressionable public that was full of anticipation and moved by the company of all the great works it found itself immersed in. Someone called out the name of Berlioz, who was hardly visible in his seat and was probably taken aback by this outpouring of enthusiasm. His name passed from mouth to mouth; people stood up and applauded; he was greeted by the entire hall. Berlioz bowed and muttered a few words of thanks. His emotion was deep; a shaft of inexpressible joy had just crossed this life of struggle and suffering. Those who were closest to him could see that Berlioz had wept; he was not the only one in the hall to do so.

Liszt, Liszt the abbot, had cheered furiously!

Ménestrel 25 March, p. 134 (unsigned): — A propos of M. Legouvé, we owe to his kindness the following lines. They relate a story told also by l’Événement : « After his ovation at the Pasdeloup concert, Berlioz received a letter signed by five people, full of the warmest feelings. As he reads this letter his satisfaction is tinged with surprise. He believes he recognises it and thinks he may have already read it somewhere. Finally, after searching long and hard, he remembers that these lines so full of enthusiastic appreciation are precisely those he wrote himself, many years before, to Spontini after a performance of La Vestale, and which he reproduced in his Memoirs. That is where those young men went to find them. Is there not something delightful in crowning a great artist with the same crown which he as a young man placed on the brow of an immortal master? »

[Note: the letter referred to is presumably CG no. 752, dated 27 August 1841; it was sent by Berlioz to Spontini after a performance of Fernand Cortez (not La Vestale), and published by him first in his Voyage musical en Allemagne et en Italie, volume I (1844) pp. 403-4 then again later in his Soirées de l’orchestre, 13th Evening. It does not appear either in the Mémoires d’un musicien nor in the posthumous Memoirs]

Ménestrel 27 December, p. 30 (anonymous review): — The most recent Concert populaire [20 December] was very fine and very interesting. The overture to Semiramis, which opened the programme, was performed faultlessly by M. Pasdeloup’s orchestra. — The Romanza and the Scherzo of the D minor symphony by Robert Schumann [no. 4] is music of beauty and strength, which cannot fail to make an impression on any musical soul. We like rather less the introduction and finale of this same symphony, in which the ideas pile on top of each other and accumulate relentlessly, and are too fragmented and nebulous. — The excerpt from Roméo et Juliette (the love scene) by H. Berlioz is also the work of a great thinker, especially the first half with its cello theme, which has such power and inspiration. — The ballet movement from Prometheus was encored as usually happens. — As for the Largo by Haydn which concluded the concert, one must have the courage to admit that it has aged somewhat.

![]()

Note: texts that are already reproduced in the page of articles and reviews covering the years 1869 to 1884 are mentioned in the table of performances below but are not listed in this section; for the full detail see that page and the table of performances in the page Paris and Berlioz: the Revival.

Ménestrel 22 November, p. 406 :— There was great uproar and great applause last Sunday [15 November] at the Concert populaire. The applause was for M. Sarasate, who gave an outstanding performance of the Beethoven violin concerto. The uproar was aroused by the prelude to Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner, which was making its first appearance on the programme of these concerts. This remarkable piece should have been performed by M. Pasdeloup long ago; it is a worthy counterpart to the prelude to Lohengrin and, like this latter piece, it will soon be understood by the section of the public that is impartial and encored without opposition. Faced with the hostility which greeted those members of the audience who wanted to have the piece played again, whether because they admired it or because they thought that a second hearing was necessary to understand a work of such elevation, M. Pasdeloup addressed the audience and announced that he would repeat the piece at the end of the concert, and that those who wanted to hear it need only stay behind, while the others could leave without losing any of the concert. All the same the majority stayed to the end of the concert and started to hiss when M. Pasdeloup raised his baton to begin again. Faced with the calm displayed by the conductor on this occasion, who made it clear that he would only signal the start of the piece when silence was completely restored, the hecklers were obliged to keep quiet or get out, and the piece was performed again with hushed attention. The number of persons who stayed for the second hearing can be estimated at one third of the audience.

Félix Jahyer, ‘Jules-Étienne Pasdeloup, fondateur des Concerts-populaires’, Camées Artistiques 8 July 1880, pp. 1-2.

Débats 11 May, p. 3 (Ernest Reyer): […] A man of complete integrity, M. Pasdeloup did not wish his reputation to be sullied in any way; his creditors were the first to get attention, he only came after. As a result, after giving everything he could, he was left with nothing or almost nothing for himself. And now he is reduced to poverty, after endowing his country with an institution of indisputable value, as are indisputable the services he has performed. If the taste for great music has spread in Paris and even elsewhere, where popular concert societies have also been founded, it is to M. Pasdeloup that the considerable honour belongs. He is the initiator, he is the first to have boldly stepped on to the breach, and he is the first to fall. […]

Ménestrel 11 May, p. 188-9 (Arthur Pougin) (excerpt): […] Thanks to his intelligent initiative, M. Pasdeloup — and that is his noblest recompense — has been able to witness a profound evolution taking place in our artistic habits and a change for the better spreading everywhere. Art, the public, and musicians have benefited from the salutary revival which he brought about so courageously. Thanks to him, the art of music in France has ceased to be confined to the theatre, it has revealed the most diverse, vast and elevated tendencies, and a whole school of young musicians which without him would not exist has demonstrated that our composers were capable of producing, away from the stage, works that deserve the highest esteem and sometimes the most sincere admiration.

That is not all. The movement he stimulated in Paris soon spread not only to the whole of France, but abroad, not only to Europe but to the New World, and it can now be said that it has invaded the whole universe. […] Concert societies for the people were set up in Brussels, London, Turin, Genoa, Florence, Milan, Madrid, Birmingham, Moscow and elsewhere. The institution reached America and settled victoriously in New York and other cities of the United States. That is what M. Pasdeloup has achieved, that is what must not be forgotten and which posterity will record, and that is why the name of the founder of the Concerts populaires has henceforward its allocated place in the noblest annals of art. […] For his part the author of these lines recalls with some happiness that when he was very young, even before the foundation of the Concerts populaires, he was a member of the orchestra that M. Pasdeloup assembled under the name of the Société des jeunes artistes, and he has fond memories of this.

ARTHUR POUGIN.

Adolphe Jullien, June 1884: ‘La retraite de M. Pasdeloup’. Excerpt: […] M. Pasdeloup was therefore the great musical « educator » of our country, as well as of the public and the composers. He initiated them first to the masterpieces of Haydn and Mozart, who were the first to be understood and celebrated, then to those of Beethoven, whose Pastoral Symphony scored a resounding success from day one, but whose other symphonies, especially the ninth, had difficulty in being accepted by the crowd. And Mendelssohn who was so keenly contested at the first concerts, and Schumann who was cheerfully heckled at every new symphony that Pasdeloup would try, and all the contemporary foreign composers, Niels Gade, Abert, Lachner, Brahms, Raff, Svendsen, Ten-Brink, Glinka, Tchaikovsky etc. whose main works he would play in turn, to the great delight of those music-lovers who were anxious to keep abreast of the music that was being produced outside France! And finally, should one mention Berlioz and Richard Wagner? Today everybody remembers with what energy he stood up to the heckling and confused shouts which would break out whenever he tried to play any piece by these great composers, whether from the Symphonie fantastique, or Lohengrin, or Tannhœuser or from la Damnation de Faust. As soon as one of these disreputable names appeared, this was the signal for a ferocious battle between the rare defenders of these two composers of genius and those who heckled without mercy. […]

There is perhaps no greater title to fame for Pasdeloup than to have fought with such tenacity to make known at least so many wonderful compositions to people who were more anxious to listen than to shout. He had already induced his normal audience to make considerable progress in that direction, but he did not reap what he had sown. It was he who worked from the very beginning to secure general acceptance of these two unrecognised geniuses, and the fruits of this obstinate labour went as regards Berlioz, to M. Colonne and to M. Lamoureux, as regards Wagner. Now that these two excellent conductors have as it were appropriated Berlioz, in the case of M. Colonne and Wagner, in the case of M. Lamoureux, it may not be untimely to insist on this point, namely that it was M. Pasdeloup who set the process in motion and invested all his energies in exalting these two great composers. […]

Ménestrel 24 October, p. 380: — This is the programme announced by M. Pasdeloup for the 25th anniversary of the creation of the Concerts populaires, next Sunday 31 October at 2 o’clock, at the Cirque d’hiver: 1. Symphony in D major, by Mozart; — 2. Andante from the third quartet, by Tchaikovsky, played by the entire string section; — 3. Symphony in C minor [no. 5], by Beethoven; — 4. Tarantella (first performance at these concerts), by C. Chaminade; — 5. XVth Rhapsody, by Liszt, played by M. Blumer; — 6. Excerpts from the opera The Mastersingers, by R. Wagner. — This programme shows that M. Pasdeloup remains true to his practices, and while preserving a foundation of classical music and works by modern masters he never forgets young composers.

Ménestrel 11 September, p. 293 (obituary notice by Arthur Pougin).

Adolphe Jullien, September 1890: ‘Pasdeloup et M. Saint-Saëns’ Excerpt: […] He had a passion for music; everything with him was instantaneous, and to his impressions and judgements he brought irresistible vehemence and sincerity. To give an example. At the end of his career, exhausted and ruined by the formidable competition of Messrs. Colonne and Lamoureux, he was attending that glorious and magnificent performance of Lohengrin at the Eden-Theatre which remained without sequel. At the end of the first act, dazzled and overexcited by the wonderful performance of the finale, he turned almost in tears to his neighbours and cried: « I have heard this twenty times in Germany, I know this piece by heart and performed it twenty times; but no, I would never have believed that it was possible to achieve such a result. Bravo, bravo, Lamoureux! » This downcast conductor did not show the slightest trace of malice, and I cannot think of any story that does him more credit. I did not know him intimately and only had intermittent dealings with him, and they would sometimes turn sour. But so what? I liked this large and exuberant man, crazy and hot-tempered, but full of fire, sincerity and conviction. And yet I did not owe him anything, and that is perhaps why I can do him justice.

Débats 10 November, p. 2 (Ernest Reyer): […] If the subsidies provided by the government to our two concert societies are insufficient, they should be doubled or quadrupled, but an institution which has performed and may still perform so many services to the art of music should not be allowed to wither away. This institution, it is to Pasdeloup that we owe it, and we must not forget this. It was he who promoted and founded it, it was he who had this idea of genius and which his successors have nurtured, it was he who cut the furrow which they followed. He may not have been a very great musician, but he had unshakable self-confidence, he had enthusiasm and daring, he could even at times be eloquent, he knew how to speak to the crowds and face the storm. A gale of whistles did not frighten him and from his numerous fights with a hostile, heated and overexcited crowd he would always emerge the victor. Who was the first to teach the Paris public to admire Berlioz, to tolerate Wagner first, and then to acclaim him?

And what has been done for this poor man since he died in harness? Does he have only a commemorative inscription, a bust on his tomb? The Paris council would do itself an honour by giving the name of Pasdeloup to one of the streets in the vicinity of the Cirque d’Hiver. If a petition is needed, I will sign it with both hands, and whenever I pass in front of the street called after the tireless apostle, in summer and in winter, through wind and snow, I will take my hat off, bald though I am. […]

![]()

The following table gives a chronological listing of all known performances of Berlioz’s music given by Pasdeloup in Paris during his career as a conductor from 1853 to 1887, together with references to sources and reviews of these concerts for the period 1853 to 1868 and 1886-1887. The list is intended to be complete but may contain gaps and errors. For the full evidence for the years 1869 to 1884 see the table of performances in the page Paris and Berlioz: the Revival; only the links to the reviews of Pasdeloup’s concerts for this period are given here. Unless otherwise stated all concerts were given by the Concerts populaires in the Cirque Napoléon, renamed in late 1870 the Cirque d’Hiver.

In the column of works the following abbreviations have been used. Carnaval = overture le Carnaval romain, Chasse royale = Chasse royale et orage from Les Troyens, Damnation = la Damnation de Faust, Enfance = l’Enfance du Christ, Fantastique = Symphonie fantastique, Francs-Juges = overture les Francs-Juges, Harold = Harold en Italie, Invitation = Invitation to the Dance (Weber, orch. Berlioz), Marche = Marche hongroise from Damnation, Menuet = Menuet des Follets from Damnation, Roméo = Roméo et Juliette, Trio = Trio for 2 flutes and harp from Enfance, Valse = Valse des Sylphes from Damnation. Where a title is mentioned without qualification (e.g. Damnation) it refers to a performance of the complete work.

| Date | Work | Sources and reviews |

| 1853 | ||

| 20 February | Carnaval (Salle Herz, Société des Jeunes Artistes) | Jullien (1890), p. 327; cf. Débats 17/3 |

| 1861 | ||

| 3 November | Invitation (Cirque Napoléon) | CG nos. 2581, 2582 and note on CG no. 3072; Ménestrel 3/11 p. 386 and 10/11 p. 399 |

| 29 December | Invitation | Holoman Cataloguep. 243 |

| 1862 | ||

| 2 March | Carnaval | Ménestrel 16/3 p. 125 |

| 30 November | Invitation | Holoman Catalogue p. 243 |

| 1863 | ||

| 22 November | Invitation | Holoman Catalogue p. 243 |

| 1864 | ||

| 28 February | Invitation | Holoman Catalogue p. 243 |

| 27 March | Troyens, Septet (Hôtel de Ville) | CG no. 2843 |

| 1865 | ||

| 22 January | Francs-Juges | CG nos. 2970, 2978; Ménestrel 22/1 p. 62 |

| 2 April | Troyens, Septet (Hôtel de Ville) | Holoman Catalogue p. 385 |

| 10 December | Invitation | CG no. 3072 and note |

| 1866 | ||

| 4 February | Carnaval | Ménestrel 4/2, p. 79 |

| 7 March | Troyens, Septet | CG nos. 3110, 3115, 3117; Ménestrel 11/3, p. 117 and 25/3, p. 134 |

| 25 March | Enfance, Part II overture | CG nos. 3122, 3124; Ménestrel 25/3, p. 136 |

| 1867 | ||

| 1 December | Francs-Juges | Ménestrel 1/12, p. 7 |

| 1868 | ||

| 19 January | Marche | Ménestrel 19/1, p. 63 |

| 1 March | Roméo part II | CG no. 3346; Ménestrel 1/3, p. 110 |

| 7 March | Marche (Hôtel de Ville) | Ménestrel 15/3, p. 126 |

| 5 April | Roméo part III; Invitation | Ménestrel 5/4, p. 151 |

| 6 December | Invitation | Holoman Catalogue p. 243 |

| 20 December | Roméo part III | Ménestrel 20/12, p. 23 and 27/12, p. 30 |

| 1869 | ||

| 7 February | Carnaval | Anon. |

| 21 March | Troyens, Septet | Ménestrel21/4, p. 128, 28/4, p. 134 |

| 14 November | Le Roi Lear | Jullien |

| 1870 | ||

| 9 January | Menuet, Valse, Marche | Jullien |

| 16 January | Invitation | |

| 30 January | Roméo III, IV, II | Jullien |

| 5 November | Menuet, Valse | |

| 1871 | ||

| 3 December | Marche | |

| 1872 | ||

| 7 January | Menuet, Valse | Anon. |

| 3 November | Damnation (excerpts) | |

| 1873 | ||

| 5 January | Francs-Juges | |

| 23 February | Fantastique | Reyer |

| 2 March | Damnation (excerpt) | |

| 16 March | Roméo (excerpts) | |

| 26 October | Roméo (excerpts) | Reyer |

| 2 November | Fantastique (4th movement) | |

| 1874 | ||

| 4 January | Invitation | |

| 1 February | Carnaval | |

| 25 October | Harold (2nd movement) | |

| 8 November | Menuet, Valse, Marche | |

| 22 November | Roméo part II | |

| 1875 | ||

| 21 February | Francs-Juges | |

| 21 November | Menuet, Valse, Marche | |

| 5 December | Invitation | |

| 26 December | Enfance (excerpts) | |

| 1876 | ||

| 9 January | Harold | Morel, Reyer |

| 30 January | Damnation (Invocation) | |

| 20 February | Carnaval | |

| 12 March | Harold | |

| 5 November | Chasse royale | Morel |

| 3 December | Menuet, Valse, Marche | |

| 31 December | Fantastique | |

| 1877 | ||

| 14 January | Fantastique | Anon. |

| 11 February | Damnation Parts I & II | Morel |

| 18 February | Damnation | Moreno |

| 4 March | Carnaval | |

| 18 March | Fantastique | |

| 28 October | Fantastique | |

| 25 November | Invitation | |

| 9 December | Roméo (excerpts) | Anon. |

| 30 December | Fantastique | |

| 1878 | ||

| 20 January | Francs-Juges | |

| 17 March | Harold | Pougin |

| 31 March | Damnation | Morel |

| 7 April | Damnation | |

| 10 October | Fantastique | Anon. |

| 17 October | Valse, Marche | |

| 20 October | Invitation, Damnation (excerpts) | |

| 1 December | Invitation | |

| 15 December | Roméo | |

| 29 December | Carnaval | |

| 1879 | ||

| 16 February | Menuet, Valse, Marche | |

| 2 March | Fantastique | |

| 20 April | Harold (2nd movement) | |

| 9 November | Fantastique | |

| 23 November | Prise de Troie Act I | Reyer |

| 30 November | Prise de Troie Acts II & III | |

| 7 December | Prise de Troie Acts I-III | Moreno, Reyer |

| [21 December] (not given) | [Prise de Troie Acts I-III] | |

| 1880 | ||

| 1 February | Carnaval | |

| 15 February | Fantastique | |

| 26 March | Rêverie et caprice | |

| 17 October | Roméo part II | |

| 5 December | Harold | Morel |

| 26 December | Trio (?) | |

| 1881 | ||

| 6 February | Invitation | |

| 13 February | Prise de Troie (aria, duet) | |

| 6 March | Damnation | Darcours |

| 13 March | Damnation | |

| 27 March | Fantastique | |

| 10 April | Damnation (excerpts) | |

| 28 May | Damnation (excerpts) (Trocadéro) | |

| [20 November] | [Damnation, cancelled] | |

| 27 November | Damnation | Pougin (?) |

| 4 December | Damnation | |

| 1882 | ||

| 12 February | Carnaval | |

| 12 March | Roméo part II | |

| 29 October | Valse, Menuet, Marche | |

| 1883 | ||

| 14 January | Invitation | |

| 9 March | Roméo (strophes) (Salle Pleyel) | |

| 2 June | Roméo (excerpts) (Eden) | |

| 21 October | Carnaval | |

| 16 December | Fantastique | Barbedette |

| 23 December | Fantastique | |

| 1884 | ||

| 2 March | Invitation | |

| 9 March | Roméo | Barbedette |

| 16 March | Roméo | de Bricqueville |

| 1886 | ||

| 28 November | Carnaval | Ménestrel 28/11, p. 419; 5/12, p. 7 |

| 1887 | ||

| 27 March | Fantastique | Ménestrel 20/3, p. 128; 27/3, p. 135; 3/4, p. 143 |

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, all the pictures on this page have been scanned from engravings, postcards, journals and other publications in our collection. The modern photos were taken by Michel Austin in May and June 2013. All rights of reproduction are reserved.

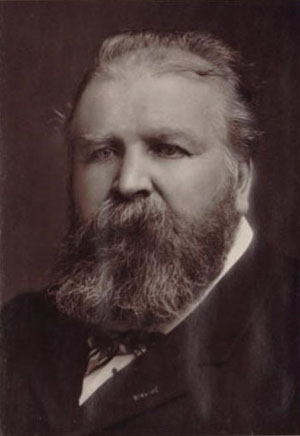

The above photo, taken by J. M. Lopez, was published on 8 July 1880 in Camées Artistiques.

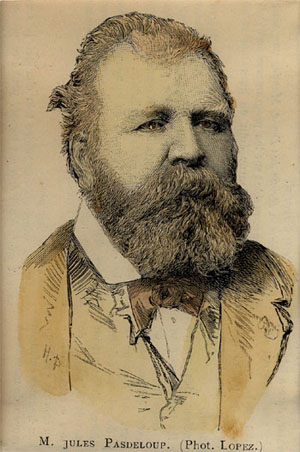

This late 19th century engraving, made after the photo taken by J. M. Lopez, is in our collection. It is obviously taken from a book or a journal but we have not been able to establish its title or exact date.

The Cirque d’hiver lies along the Boulevard du Temple. The Square in front of it is named after Pasdeloup.

Pasdeloup conducted the Septet from Les Troyens at two concerts in the Hôtel de Ville on 27 March and 2 April 1864.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Page Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions created on 15 March 2012; this page created on 15 March 2012, and enlarged on 1 August 2013.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.

![]() Back to Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions

Back to Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions

![]() Back to Paris and Berlioz: the Revival

Back to Paris and Berlioz: the Revival

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page