![]()

Chronology

Introduction

1843

1853

The sequel

Concert programmes

Leipzig in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

March: Berlioz meets Mendelssohn in Rome

Schumann publishes in Leipzig a series of articles on the Fantastic Symphony in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik

November: performance of the Francs-Juges overture in Leipzig

March: the Euterpe Society of Leipzig awards Berlioz a Diploma

28 January: Berlioz travels from Weimar to Leipzig

30 January: first meeting of Berlioz and Schumann

31 January: first rehearsal, Schumann in attendance

2 February: Berlioz travels from Leipzig to Dresden and back to arrange concerts there; in the evening he attends a concert by Mendelssohn

3 February: second rehearsal

4 February: first concert in the Gewandhaus

6-19 February: Berlioz in Dresden

12 February: Berlioz orchestrates Absence in Dresden

19 February: Berlioz returns from Dresden to Leipzig

22 February: second concert (charity concert) in the Gewandhaus

27 February: Berlioz visits the Schumanns, but is unwell

28 February: Berlioz departs from Leipzig for Brunswick

23 November: Berlioz travels from Bremen to Leipzig

1 December: first concert in the Gewandhaus

10 December: second concert in the Gewandhaus

13 December: Berlioz leaves Leipzig for Paris

April: publication of a German edition of The Flight to Egypt by Kistner in Leipzig

![]()

It was through Mendelssohn that Berlioz was invited to Leipzig in 1843, but the connection dated from many years earlier. When Berlioz arrived in Rome in March 1831 Mendelssohn was one of the persons he met there, and he was immediately impressed. In years to come he retained the positive view he formed then of Mendelssohn as man, musician and composer, despite the great differences in temperament and outlook between the two men. Many years later Berlioz was to relate his Italian experiences of Mendelssohn in the fourth letter of the series Voyage Musical en Allemagne [Musical Travels to Germany], first published in the Journal des Débats on 3 September 1843 (Critique musicale vol. V pp. 285-95). Together with the other letters in the series it was soon republished in the first of the two volumes of Voyage musical en Allemagne et en Italie of 1844, and was eventually incorporated in the posthumous Memoirs more or less as originally published (with a few additional footnotes). The account given there can be compared with the letters Berlioz wrote from Italy at the time, the earliest of which, addressed to a series of friends in Paris, is dated 6 May 1831 when Berlioz was in Nice (Correspondance Générale no. 223, hereafter CG for short):

[…] I found Mendelssohn [sc. in Rome]; Montfort knew him already and we quickly got together. He is a wonderful person; his talent as a performer is as great as his musical genius, and that is saying a great deal. Everything I have heard of him has delighted me; I firmly believe that he is one of the highest musical talents of our time. He has been my guide in everything; every morning I would go to find him, he would play me a Beethoven sonata, we would sing Gluck’s Armide, then he would show me around all the famous ruins which I confess did not impress me very much. Mendelssohn is one of those pure souls such as are very rarely found; he believes with conviction in his Lutheran religion, and I would sometimes shock him deeply by making fun of the Bible. I owe to him the only bearable moments I have enjoyed during my stay in Rome. […]

On 16 May Berlioz wrote in similar terms to his father (CG no. 228), and letters to other correspondents later in the year give a similar view (CG nos. 241 [17 September]; 251 [3 December]). Mendelssohn eventually left Rome in September 1831 (CG no. 241); mentions of him in Berlioz’s correspondence continue during 1832 (CG nos. 256, 265, 270, 280, 284) but then cease for years to come. It was to be a long time before the two men met again, but Mendelssohn was firmly established in Berlioz’s mind as one of the leading composers of the age. References to him in Berlioz’s critical writings of the 1830s are almost invariably positive (e.g. Critique Musicale vol. I p. 160; III p. 286; IV pp. 42, 83; V pp. 47-9, 77f., 93), and the same remains true later in Berlioz’s career (see for example Journal des Débats 26 May 1844; 12 August 1851; 27 July 1853). One might add that Mendelssohn’s Jewish origins were an irrelevance as far as Berlioz was concerned (the same is true of his attitude to Halévy and Meyerbeer), and later he was to take issue with the Russian critic Wilhelm von Lenz on that score.

On his side Mendelssohn was much more reserved about the French composer and his works, as Berlioz later found out, but he did not allow this to affect the outward cordiality of their relations. In 1835 Mendelssohn was appointed musical director of the Gewandhaus orchestra in Leipzig, and the following year his friend the violonist Ferdinand David (1810-1873) became leader of the orchestra, a post he held to the end of his life. Under Mendelssohn’s direction Leipzig’s musical life achieved high standards, but in comparison with its near-neighbour and rival Dresden it was also thought of a bastion of conservatism which prided itself on its undemonstrative seriousness.

It was however thanks not to Mendelssohn but to Robert Schumann that Berlioz’s connections with Leipzig seemed to take a promising start in the 1830s. In 1834 Schumann founded in Leipzig the journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, in which he published the following year a detailed study of Liszt’s transcription of the Fantastic Symphony which had appeared the previous year (CG nos. 342, 357, 416, 453). From 1836 to 1839 he and Berlioz were in intermittent correspondence (CG nos. 472bis, 475bis, 485bis, 485ter, 496bis, 619bis [all in vol. VIII]). In February 1837 Berlioz published in the Revue et Gazette Musicale a long open letter addressed to Schumann thanking him for a performance of the Francs-Juges overture in Leipzig in November 1836 but explaining why he was anxious to go to Germany to take personal charge of the performance of his works (Critique Musicale III pp. 37-40, reproduced in CG no. 486). In March 1838 the Euterpe Society of Leipzig awarded Berlioz their Diploma and it was Schumann who reported the honour to Berlioz (CG 548bis [in vol. VIII]). In the same year the Revue et Gazette Musicale reported a performance of the Francs-Juges overture in Cologne directed by Mendelssohn himself. In 1839, the celebrated pianist Clara Wieck, who was to become Schumann’s wife the following year, came to Paris. This prompted an appreciative letter of Berlioz to Schumann (CG no. 630, 14 February; cf. 645bis [in vol. VIII]), though Berlioz’s review of a concert by her may not have been as generous in praise as Schumann or Clara Wieck had hoped (Journal des Débats 18 April 1839). There is thereafter a gap in the correspondence between the two men until 1843, though from 1840 the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik started to republish in Leipzig articles by Berlioz which were appearing in Paris journals.

![]()

Because of his connections with Mendelssohn and then Schumann Leipzig was a natural destination for Berlioz on his first major trip to Germany (CG no. 791), and the proximity of Dresden suggested planning a visit to the two cities together. While in Weimar early in 1843 Berlioz wrote on the same day (23 January) to Lipinski in Dresden (CG no. 803), whom he had previously met in Paris, and to Mendelssohn in Leipzig (CG no. 804):

It is a long time since we lost sight of each other, and in our quest for beauty we have probably followed different paths, whether parallel or divergent. I have nevertheless no hesitation in asking for your assistance in putting on performances of some of my compositions for the Leipzig public. […]

Mendelssohn replied promptly and positively with useful practical information; he also recommended that Berlioz participate in a charity concert to be given on 22 February. Berlioz quotes the letter in his Memoirs, though in a condensed form (for the fuller original see CG no. 805, 25 January). He replied to Mendelssohn immediately with his travel plans and suggestions for the first concert on February 4 and the later charity concert, and ended (CG no. 806, 26 January):

[…] You will not believe how happy I feel at seeing you again and how keen I am to renew a friendship of which I am so proud, and which to my great regret has vanished into the twilight.

Whether this friendship enters a new dawn or returns to dusk will not depend on me. […]

Berlioz travelled from Weimar on 28 January and arrived the same day in Leipzig (CG no. 806), where he stayed at the ‘Hôtel de Bavière’ (Bayern Hotel), where he was to stay again in 1853 (CG nos. 806, 810, for 1843; 1657, 1661, 1664, 1669, for 1853; the location of the hotel is apparently unknown). According to the Memoirs Berlioz arrived in time to hear Mendelssohn rehearsing his Walpurgisnacht, a work which impressed him greatly. The reunion of the two men was friendly, and they decided to exchange batons. Berlioz received Mendelssohn’s on the spot, and sent his to Mendelssohn with a letter dated 2 February. The letter is cited in the Memoirs and is also preserved in an autograph copy (CG no. 813). February 2nd was a very busy day: as well as writing this letter and at least 3 others (CG nos. 810, 811-12), Berlioz travelled by train to Dresden to make arrangements for his forthcoming visit (cf. CG no. 812), returned in the afternoon to Leipzig, and in the evening attended a concert conducted by Mendelssohn. He wrote the same day to Chélard in Weimar (CG no. 810; cf. 820 to his father, 14 March):

[…] I am back from Dresden where everything is organised. I am giving a concert here on Saturday [4 February]; I have already conducted one rehearsal, the orchestra is admirable, excellent, and so is Mendelssohn.

I am horribly tired after travelling 70 leagues today by rail. […]

The next day (3 February) he conducted his second rehearsal; it included the song Absence sung by Marie Recio. In an album he carried with him on the trip to Germany Berlioz wrote out the opening stanza of the song, with the date 3 February and the comment ‘after the rehearsal where Marie sang very well’ (David Cairns, Berlioz vol. II [1999], 243f.; there is a reproduction of the autograph in Damnation! Berlioz et l’Allemagne [2006] p. 23). As Berlioz notes, the rehearsals were very efficiently managed, thanks to the discipline promoted by Mendelssohn and Ferdinand David, who were both unfailingly helpful. But Berlioz felt it necessary to increase the number of violins from 16 to 24 – the shortage of strings was a recurring problem with many German orchestras of the time, as was the difficulty of providing players for the cor anglais, ophicleid and harp parts which Berlioz could take for granted in Paris (cf. CG no. 812). The programme of the concert in the Gewandhaus on 4 February comprised the overtures King Lear and Les Francs-Juges, the Rêverie et caprice with Ferdinand David as soloist, the melodies Absence and Le Jeune pâtre breton, both sung by Marie Recio, and the Fantastic Symphony. Berlioz departed for Dresden on 6 February where he was to give two concerts. The day before his return to Leipzig he wrote from Dresden to his friend Auguste Morel (CG no. 815, 18 February):

[…] I also gave in Leipzig a fine though unproductive concert [sc. as compared with those in Dresden], and I am going back there to conduct the finale of Romeo and Juliet; Mendelssohn is rehearsing the chorus in my absence; I will then go to Berlin where Meyerbeer is expecting me. […]

Berlioz’s original intention had been to include the finale from Romeo and Juliet as his contribution to the charity concert on 22 February (CG no. 806), though as the Memoirs relate, the inadequacy of the singer who was to take the part of Friar Lawrence forced Berlioz to change the programme at the last minute, thus wasting all the rehearsal time that Mendelssohn and he had expended on the work. Lipinski, who had come from Dresden specially to hear the piece, was disappointed. Berlioz substituted the King Lear overture and Absence (sung by Marie Recio), which had been performed at the concert on 4 February, and the Offertorium from the Requiem which presented no difficulty to the chorus (the letters Berlioz wrote after this concert make no mention of the enforced change of programme). On the day of his departure from Leipzig Berlioz gave to his friend Joseph d’Ortigue a general account of his time in Leipzig (CG no. 816, 28 February):

[…] I should have written to you long ago, but I have been working like a galley-slave and this seems to me a sufficient excuse for the delay. I have been ill and am still unwell because of the unbelievable stress caused by the rehearsals in Dresden and Leipzig. Imagine that in twelve days in Dresden I have conducted eight rehearsals of 3 1/2 hours each and given two concerts, that on one occasion I had to make the journey from Leipzig to Dresden and back the same day, that is 60 leagues by train, prepare my two concerts and come back to help in the concert Mendelssohn was conducting here. Mendelssohn has been charming, excellent, considerate, in short a perfect friend; we have exchanged batons as a token of friendship. He is a very great master, and I say that in spite of his enthusiastic compliments for my romances – the fact is that he has never said a word to me about the symphonies, overtures or the Requiem. He performed here for the first time his Walpurgisnacht on a poem by Goethe, and I can assure you that it is one of the most wonderful orchestral compositions you could hear. Schumann, the reticent Schumann, is completely electrified by the Offertorium of my Requiem; he opened his mouth the other day, to the great amazement of those who know him, grasped my hand and said: this Offertorium surpasses everything.

In truth nothing has made such an impression on the German public; for several days the Leipzig papers have not ceased talking about it and asking me to perform the Requiem in its entirety, which is impossible since I am leaving for Berlin and because the resources necessary for the large-scale movements cannot be found here.

[…] Here [sc. in Leipzig] I gave a concert [on 4 February] which included the King Lear overture, the Fantastic Symphony, which left them astonished rather than moved, etc. The finale (the Sabbath) was performed with a precision and diabolical fury without example. I was then asked for a few pieces for a charity concert for the poor [on 22 February] and I gave them again King Lear, a melody with orchestra [Absence, sung by Marie Recio], and the eternal Offertorium. These three pieces have definitely swept the Leipzig audience off their feet. […]

Berlioz went on to Brunswick (and not Berlin as he originally thought); on 6 March he wrote from there to his friend the cellist Desmarest, mentioning among the other pieces the success of Absence – ‘I have orchestrated it and it was really very well sung’ – , but without naming Marie Recio (CG no. 817). The autograph score of Absence bears in fact the indication ‘Orchestrated in Dresden on 12 February 1843 and copied out in Brunswick on 12 March’ and is inscribed ‘Pour Marie’ (the first performance of the orchestral version of the song took place in Dresden on 17 February). The same day (6 March) he wrote to his friend Auguste Morel: ‘On my return from Dresden the Offertorium turned the heads of the Leipzig audience, and for several days the papers asked for it to be repeated, demanding a complete performance of the Requiem. Those who told you the German papers were keeping quiet about my concerts do not know what they are talking about, or perhaps they know all too well’ (CG no. 818).

The Memoirs mention the approval expressed by ‘the reticent Schumann’ for the Offertoire of the Requiem; this is the only reference to the German composer in the whole of the Memoirs (whereas Mendelssohn is referred to with some frequency there and in Berlioz’s other writings). The diary kept by Clara and Robert Schumann shows that there was in fact more contact during Berlioz’s stay in Leipzig than Berlioz himself reveals (see David Cairns, Berlioz II [1999], 282, 286). Schumann and Berlioz met shortly after his arrival in Leipzig and again at subsequent rehearsals. Berlioz was invited to the Schumanns’ on 27 February; Clara was critical of Berlioz’s apparent coldness (though Berlioz was unwell), while Robert continued, despite reservations, to be intrigued by the French composer, to whom he offered various presents, as letters show, though Berlioz excused himself for being unable to reciprocate (CG nos. 815bis and 816bis [both in VIII], 27 and 28 February). Schumann wrote again to Berlioz in Berlin, apparently suggesting the publication of works by Berlioz in Germany, and Berlioz replied from Hanover on 28 April (CG no. 831bis [in vol. VIII]). This is the last known exchange of letters between the two men (they met casually in Berlin on 19 April 1847 when Berlioz was on his way to Russia). It seems therefore that the promise of the 1830s remained unfulfilled and the two composers drifted apart. One important reason was communications: neither spoke the other’s language, and it is the case that otherwise all the German musicians or music-lovers with whom Berlioz became close (such as Robert Griepenkerl) could speak and write French with sufficient fluency.

Though Berlioz never saw Mendelssohn again he remained in touch. In 1845 while on a trip to Marseille he wrote to him recommending a German oboe player who was keen to return to his country, and asked: ‘What news of you? When the electric telegraph between Leipzig and Paris is installed I imagine that you will send me your news from time to time’ (CG no. 971, 29 June). The following year, during his stay in Prague, he wrote again (CG no. 1033, 14 April 1846):

[…] I fear I may be unable to go and shake your hand while travelling through Leipzig [sc. on the way from Prague to Brunswick]. It is a matter of keen regret. Allow me to say that I heard in Breslau your Midsummer Night’s Dream and that I have never heard anything so profoundly Shakespearean as your music; on coming out of the theatre I would willingly have given up three years of my life to be able to embrace you. […]

P.S. Please give my regards to one of your friends, M. David, a true artist.

Mendelssohn died on 4 November 1847 aged 38, and Berlioz, now in London, wrote not long after to Henry Chorley (CG no. 1139; cf. 1144, 1987):

[…] You cannot doubt that I share your sadness. Though I was not as intimately acquainted with Mendelssohn as you are, I nevertheless knew him very well, and in any case even had he been a total stranger to me I would mourn him as a great artist and a mind of exceptional distinction.

It is a harsh blow that death has dealt to serious and dignified music, and we must all feel it deeply. […]

![]()

When Berlioz resumed his travels to Germany in 1852 and 1853 he probably did not envisage at first returning to Leipzig. He had been well received there a decade earlier, but the relative conservatism of the city’s musical life did not provide as inviting a setting as other German cities, though his devoted supporter J. C. Lobe – ‘this example of the true German musician’ (Memoirs) – had moved in 1846 from Weimar to Leipzig where he edited his own paper (cf. CG nos. 1444, 1655, 1663bis [in vol. VIII]). During or shortly after his visit to Weimar in November 1852 Berlioz apparently received an approach from Leipzig to let them perform his Faust there, but he was wary of letting this take place in his absence (CG nos. 1543, 1560bis). When he set out for Germany in October 1853 his destinations included Brunswick and Hanover, and possibly Bremen, but not Leipzig (CG nos. 1629, 1630, 1632-3). But while in Hanover he received an invitation from Ferdinand David in Leipzig to which he replied on 7 November (CG no. 1643):

Griepenkerl has just arrived here from Brunswick and has passed on to me the very kind letter you wrote to him. Be assured that I am very keen to present some of my latest compositions in Leipzig, though I do not presume in any way to change the practices of the Gewandhaus Society on this occasion. I am not after money, and believe I have demonstrated this long ago. All I seek is the possibility of acting in an artistic way. So if you believe that I can give with advantage a concert in the course of December for myself, after having been heard in one of your own concerts, here is what I suggest:

[Berlioz goes on to make suggestions for part of a concert at the Gewandhaus, enquires about a possible second concert consisting solely of his own music and including excerpts from the Damnation of Faust, and asks:]

Whether I could have the necessary singers for Faust (tenor), Mephisto (bass), Brander (bass), and Marguerite (mezzo-soprano). If yes, I could send you soon the parts and vocal scores. But I would ask you in confidence whether these singers are gods or just human beings; I would like to deal solely with human beings, unworthy as I am of frequenting deities; all the same these human beings have got to be musicians. […]

David responded quickly, and over the next few days several letters were exchanged concerning the preparations for Berlioz’s visit (CG nos. 1646-7, 1747bis [in vol. VIII]), in the first of which Berlioz noted ‘I see that your Gewandhaus orchestra has been considerably strengthened in respect of the number of players’. On 13 November, still in Hanover, Berlioz wrote to Griepenkerl (CG no. 1649):

[…] David is writing me charming letters which encourage me to expect his warmest support in Leipzig, whatever may be his musical opinions of me. He is a decent man.

Farewell, very dear friend, I rather hope to see you in Leipzig or at least to shake your hand while travelling through Brunswick on the 23rd. I do not know at what time the train from Leipzig stops at Brunswick station, but you will know this yourself. […]

From Hanover Berlioz went to Bremen where he gave a concert (22 November); the day after he travelled in the morning to Leipzig (CG nos. 1646-7, 1649), where preparations for his two concerts, on 1 and 10 December, started without delay (cf. CG no. 1654). On 30 November he wrote to his sister Adèle (CG no. 1657):

[…] Here [in Leipzig] the omens for tomorrow’s concert [1st December] are good. Financially this one is not for myself but matters only from the honorific point of view. It is a concert of the dreaded and difficult Gewandhaus Society, the musical centre of Germany, for which my compositions are providing the staple fare almost on their own. There is only a Beethoven symphony at the start; all the rest is my own. This morning, such was the stir caused in the city by the previous rehearsals that the hall was half-full with interested visitors. Everyone was in a state of exhilaration, which was all the more gratifying for me as here they are more difficult and choosey. There are eighty amateur ladies singing in the chorus, with some sixty children and (musical) merchants and the choir-boys from St Thomas Church. It is magnificent. This morning I heard for the first time in its entirety my Mystery on The Flight to Egypt, from which the piece called The Holy Family at rest scored such a success in London and in all the German cities which I have just visited. It is really good, it is innocent and touching (do not laugh), in the style of the illuminations of old missals. Everyone says that I have caught to perfection the right colour for this Biblical Legend, and I am being urged to continue this work by doing now The Holy Family in Egypt. I would be happy to do this, because the subject enchants me, when I have found the documents I lack on Jesus’ stay in Egypt; I am writing the words as well as the music. […]

Liszt is arriving tomorrow from Weimar to attend the concert. I will be giving one for myself in ten days. The Academy of Song which I mentioned to you earlier has already started rehearsing the choral parts. This concert will involve some significant expenses, even though the singers are not asking to be paid; but I should be able to manage. […]

On 3 December, after the concert, he sent a letter of appreciation to the Academy of Song in Leipzig (CG no. 1658):

In the last Gewandhaus concert you have performed several of my compositions with such excellence, and such a fine feeling for the most exquisite musical nuances, that I cannot but express to you my gratitude and admiration.

Allow me to say also how touched I am by your kindness in coming to my assistance for my concert, and by the good grace with which you are prepared to submit to tedious rehearsals. These marks of interest are more flattering for me than I can say, and I beg you to receive in return my warmest thanks. […]

On the same day he wrote to Robert Griepenkerl (CG no. 1659; a reproduction and full translation of this letter is available on this site):

[…] The Gewandhaus concert was very brilliant and lively for Leipzig. Everyone says that I scored a great success; one has to believe this, despite the coldness of this public, which I cannot help comparing with the warmth of the public in Brunswick, Hanover and Bremen. The piece which was most successful with this unusual audience was the small oratorio The Flight to Egypt, performed complete for the first time. There are now violent arguments between my supporters and the others. This morning’s Tageblatt has a very fine article by M. Gleich, very warm and very intelligent.

The musicians and amateurs of the Academy of Song are very good to me; as for David, who played the viola part of Harold in a masterly way, he is admirable, courteous, active, friendly, in short perfect.

At my concert [on 10 December] we are giving the first two parts of Romeo, with the choral parts, prologue, etc. Then once more The Flight to Egypt and the first two acts of Faust. […]

On 5 December he wrote to Lipinski in Dresden (CG no. 1660):

[…] Everything here is going well, the newspapers, the public and the musicians are treating me very well. Local prejudices are fading; time has moved on. My only fault in the eyes of some of the people of Leipzig is that I am not a German. There is no remedy for this, and I must resign myself to being a Frenchman. […]

P.S. my concert will take place on the 10th of this month; it is the eve of my birthday; on my return I will drink to your health around ten o’clock in the evening, so drink to mine at the same time.

On 9 December, the day before the second concert, he writes to Joachim in Hanover and tells him of his meeting with the young Brahms (CG no. 1664):

[…] I am staying here till next Tuesday [13 December]. My concert is taking place tomorrow. All is going well. Despite their air of coldness the people of Leipzig are hooked. All the newspapers have treated me admirably. The opposition is fuming and we treat it with scorn. […]

[…] Brahms is having a great success here. The other day at Brendel’s I was very impressed by his Scherzo and his Adagio. I thank you for introducing me to this bold but so timid young man who dares to write new music. He will suffer a lot…

As for my admiration for you it is growing since I left you. And when I reflect on your musical worth, so complete, brilliant and pure, I sometimes catch myself saying aloud, for no special reason « But this is colossal, this is prodigious! » […]

P.S. David is very good, very courteous, and very cautious. He knows his people here in Leipzig, and I have benefited greatly from his advice. He is a true artist… a man of wit… which never does any harm. […]

Two days after the concert, on 12 December, he wrote again to Joachim (CG no. 1667):

[…] The concert two days ago was fantastic. In this morning’s Tageblatt there is a superb article which I will bring to you tomorrow. The students came after the concert to serenade me. Everyone is pleased and so am I. […]

Berlioz had evidently hoped to meet Joachim at the station in Hanover on his way from Leipzig, but misread the timetable, as shown by another letter to Joachim the following day: ‘Excuse my absent-mindedness. I gather that we are not going via Hanover, so please do not come to the railway station to get frozen’ (CG no. 1667bis [in vol. VIII]).

Back in Paris Berlioz sent a detailed account of his experiences in Leipzig to his sister Adèle (CG no. 1669, 17 and 19 December):

Your letter arrived in time, I was still in Leipzig and it crowned one of my great joys. I had just given my concert and scored the most important success I can aspire to in Germany. This dreaded Leipzig public has thawed. Once more the entire press has declared for me; after the concert I was recalled with applause which reminded me of Hanover and Brunswick. An hour later the students came to the Bayern Hotel to serenade me. The next day (they knew it was my birthday), in a soirée where I happened to be, a young lady came to present me with a crown and to read to my face (in a French prose translation) lines written for the occasion by a poet from Dresden during the day. Then the musicians refused to accept the payment agreed for the concert. Their leader (Ferdinand David) tells me that nothing of the sort has ever been seen in Leipzig. This must have very positive and highly significant consequences for me in the whole of Germany. I have only one misfortune left, that of being a Frenchman. This visibly worries them. The ladies from the Academy of Song were saying to me the other day with a note of impatience: « But why do you not speak German, Mr. Berlioz? It ought to be your language. You are a German: what is the use of your speaking English? You sometimes inadvertently use English phrases when addressing the musicians. You must speak German. » […]

![]()

The success of the Leipzig concerts of December 1853 seemed to Berlioz to mark a turning point in his fortunes in Germany. In chapter 59 of the Memoirs, which is dated 18 October 1854, Berlioz notes the warmth he had recently experienced in Germany:

The reception I get there gets better all the time; the sympathy shown to me by the musicians grows by the day; those of Leipzig, Dresden, Hanover, Brunswick, Weimar, Karlsruhe, and Frankfurt have lavished on me marks of friendship for which I cannot express adequate thanks.

But the same chapter also includes a comment about Leipzig specifically:

In Leipzig also, though my music is heard nowadays with different ears than in Mendelssohn’s time (as I have been able to see for myself, and as I am assured by Ferdinand David), there are still a few little fanatics, pupils of the Conservatory, who, without knowing why, regard me as a wrecker, an Attila of musical art, and honour me with furious hatred, send me insults in writing and pull faces at me behind my back in the corridors of the Gewandhaus.

At the end of 1853 the outlook seemed nevertheless promising. On 18 December Berlioz wrote from Paris to Ferdinand David sending him several scores – the Requiem, Sara la baigneuse and Tristia – with a view to future concerts, and wondered even whether Benvenuto Cellini might be performed in Leipzig (CG no. 1668). The publisher Kistner of Leipzig was encouraged by the success of The Flight to Egypt to issue a German edition of the work; it appeared in April 1854 and was dedicated to the Leipzig Academy of Song (cf. CG nos. 1685, 1688 [with vol. VIII], 1731, 1731bis [in vol. VIII], 1736, 1745, 1751).

But complications soon arose. During Berlioz’s absence from Paris in November and December 1853 the Polish count Tadeusz Tyskiewicz, who edited a musical journal in Leipzig, brought a case against the Paris Opéra for staging a mutilated version of Weber’s Der Freischütz, and Berlioz found himself absurdly implicated in the affair: it was after all thanks to him that in 1841 the Paris Opéra had staged the first complete version in France of Weber’s masterpiece. Berlioz wrote an open letter to set the record straight, which was published in several Paris papers and which he sent to many friends in Germany for publication in the German press (cf. CG no. 1682, to Baron Donop). Yet on 6 January 1854 he received a letter from a student in Leipzig named Wisthling accusing him of mutilating Weber’s work, followed by a second in which the student claimed to be speaking on behalf of the same student body which a few weeks earlier had serenaded Berlioz… In his reply Berlioz promptly put the student back in his place: ‘Let me inform you that I have given more proofs of my religious respect for the great German masters than you could provide in the whole of your life, and that on that score I am above accusations and superficial judgements’ (CG no. 1684, 7 January). The same day, visibly upset, he raised the matter in a letter to Ferdinand David: ‘All this is revolting in its injustice and absurdity’ (CG no. 1685).

Berlioz’s hopes of further performances in Leipzig failed in the end to materialise. Unexpectedly, the text of Sara la baigneuse was felt in Leipzig to offend good taste, and Berlioz asked for the return of the work ‘which shame almost prevents me from naming … given the extreme danger of asking the Ladies of your Academy of Song to sing such indecencies, it will be of no use to you’ (CG no. 1731, to Ferdinand David, 11 April; cf. 1668, 1688). Hopes for a German edition by Kistner in Leipzig of the completed Enfance du Christ also came to nothing and the plan was eventually abandoned by the publisher in 1856 for reasons of cost (CG nos. 1755bis [VIII], 1934, 1983, 2012, 2095). During 1855 Berlioz had in fact toyed with the idea of a complete edition of all his works, to be published by Härtel in Leipzig with the assistance of Liszt, but the project was not to be achieved in his lifetime (CG no. 1901, cf. 1908, 1913, 1918, 1965). Relations with Ferdinand David remained cordial, but seem to have ceased after 1855 (cf. CG no. 2012, 10 September 1855). The only enduring link with Leipzig remained the faithful J. C. Lobe: on 5 April 1863 while in Weimar for a performance of Beatrice and Benedict Berlioz wrote to him hoping he would be able to come (CG no. 2707bis [in vol. VIII]).

![]()

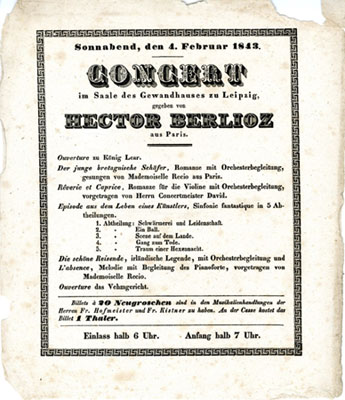

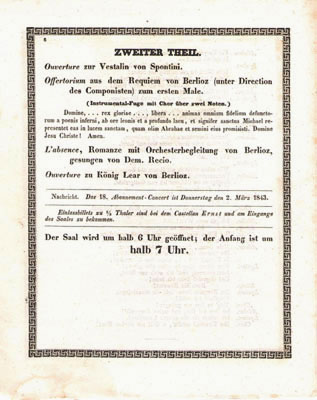

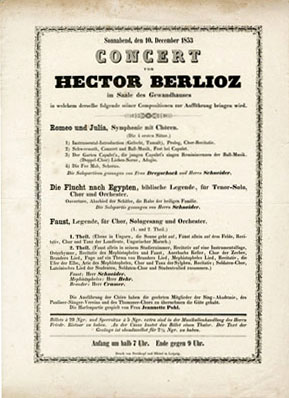

This section presents scanned images of the programmes of Berlioz’s concerts in 1843 and 1853. The original copies of these programmes were donated by us to the Hector Berlioz Museum in 2014. © Hector Berlioz Museum. All rights of reproduction reserved.

[p. 1]

|

[p. 2]

|

[p. 3]

|

[p. 4]

|

![]()

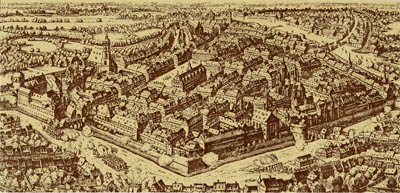

Unless otherwise stated, all the modern phonographs were taken by Michel Austin in 2008; all other pictures have been scanned from 19th- and early 20th-century engravings, postcards, newspapers, and books in our collection. © Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb. All rights of reproduction reserved.

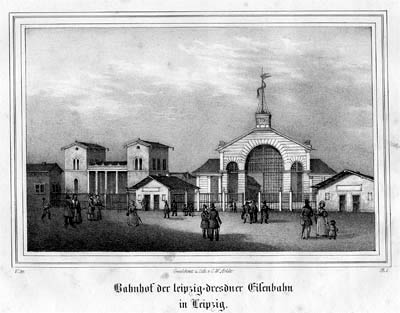

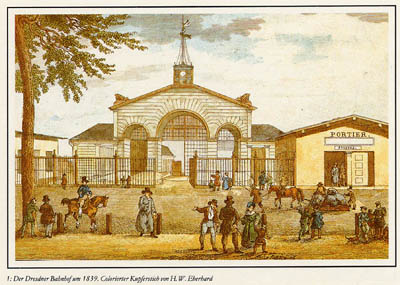

Berlioz would have taken his train to Dresden at this station on 2 February 1843. See also A Train Journey to Dresden in 1843.

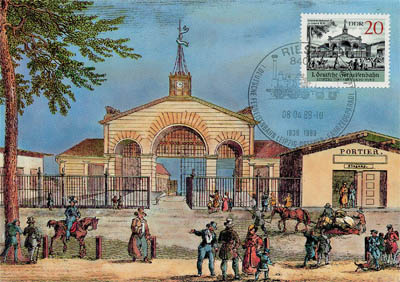

The above first day cover postcard and stamp of 8 April 1989 commemorates the 150th anniversary of the inauguration of the Leipzig-Dresden line in 1839, which was the first railway line in the country.

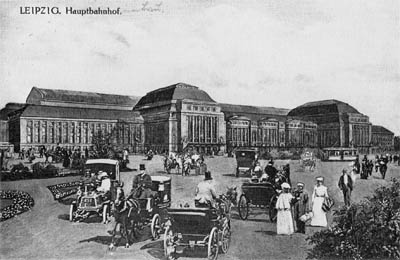

The Leipzig Hauptbahnhof was built between 1909 and 1915 and inaugurated in October 1915. It replaced the existing four stations in the city, of which the Leipzig-Dresden station was one. The new central station was severely damaged in 1944 by the allied bombardment, and was reconstructed later.

The above photo is courtesy of Hugo Johst, Leipzig in alten Ansichtskarten (Weidlich Verlag, 2001), a copy of which is in our collection.

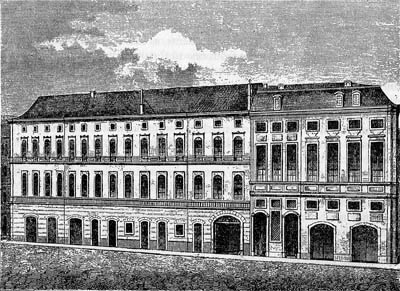

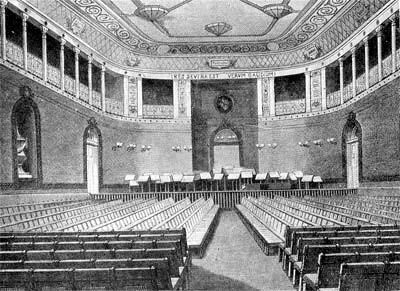

The Gewandhaus (‘Cloth Hall’) was the first adequate concert hall in Leipzig; it was built near the centre of the town in University Street [Universitätsstraße] by the architect Johann Carl Friedrich Dauthe in 1781, and the first concert in the hall was conducted by J. A. Hiller on 25 November that year. In 1835 Mendelssohn was appointed the conductor of the Gewandhaus orchestra, a post which he held until his death in 1847.

In 1842 another storey was added to the old building, and galleries provided more room for the growing audiences. The hall was redecorated, and gas lighting was substituted for the oil lamps.

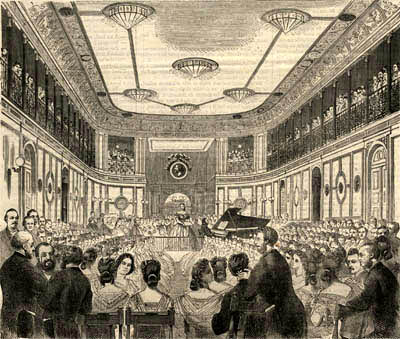

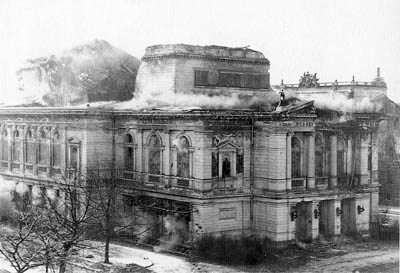

The Gewandhaus orchestra continued to play in this building till 1884, when a new and larger Gewandhaus was built on a different site, the Königsplatz, further away from the centre. The original building continued to exist for another decade until it was eventually demolished in 1895. The second Gewandhaus, on the Königsplatz, was destroyed in an allied aerial bombardment during World War II. The third, and present, Gewandhaus was built on Augustplatz; the chief architect was Rudolf Skoda. It opened on 8 October 1981 and includes a Mendelssohn Hall as well as the Great Hall which is its main concert hall.

The above picture is courtesy of Adam Carse, The Orchestra from Beethoven to Berlioz (Cambridge, 1948), p. 131.

The above engraving is courtesy of Rudolf Skoda, Die Leipziger Gewandhaus Bauten (Verlag Bauwesen, 2001), p. 26.

The above picture is courtesy of Adam Carse, op. cit. facing page 140.

The above engraving was published in Le Journal illustré, no. 48, 8-15 January 1865. The singer in the picture is Carlotta Patti, Adelina Patti’s elder sister.

The above watercolour by Gottlob Theuerkauf (1833-1911) is dated 1895. The picture is courtesy of Rudolf Skoda, Die Leipziger Gewandhaus Bauten (Verlag Bauwesen, 2001), p. 32.

The above picture is courtesy of Rudolf Skoda, Die Leipziger Gewandhaus Bauten (Verlag Bauwesen, 2001), p. 30.

The above picture shows a concert conducted by Carl Reinecke. The picture is courtesy of Rudolf Skoda, Die Leipziger Gewandhaus Bauten (Verlag Bauwesen, 2001), p. 48.

The Mendelssohn monument in front of the building, which had been erected in 1892, was removed by the Nazi regime in November 1936. In 2008 a new monument, recast after the original, was inaugurated in Leipzig, not far from the Thomaskirche (St. Thomas Church).

The above photo is courtesy of Rudolf Skoda, Die Leipziger Gewandhaus Bauten (Verlag Bauwesen, 2001), p. 75.

On the wall of the building to the left of the above photo (where the man in red is passing by) there is a large metal plaque which commemorates the original Gewandhaus (see the next 3 photos).

The English translation of the text reads:

Here stood the Gewandhaus,

The trade hall of the cloth merchants.

For a transcription of the original text and its English translation see the large view.

![]()

See also on this site:

Faust in Leipzig

A Train Journey from Leipzig to Dresden in 1843

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; the page Berlioz in Leipzig was created on 3 January 2007; enlarged on 1 January 2012, and on 1 November 2014. Revised on 1 March 2024.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb.