![]()

The Villa Medici

Horace Vernet and his family

Berlioz’s fellow laureates at the Villa Medici

The Villa Medici and Berlioz in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

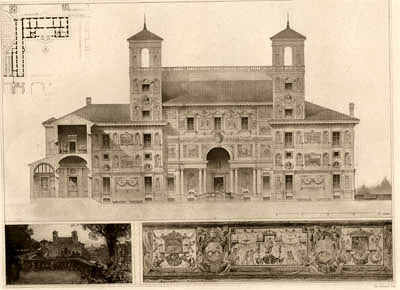

Created in 1666, the Académie de France had many homes in Rome before moving from its first home in the Palais Mancini to the Villa Medici in 1803. It was thereafter attached to the Institut de France, and the competition for admission, the « Prix de Rome », which Berlioz won in 1830, was managed by the Académie des Beaux Arts. At the time of Berlioz’s stay, the director of the Académie was the painter Horace Vernet (1789-1863), who had been appointed in 1828; he was to be succeeded in 1835 by another painter, Ingres.

Berlioz arrived in Rome in March 1831 after an eventful crossing from Marseille to Livourne; there is a graphic account of the journey in the Memoirs (chapter 32) and also in a long letter he wrote from Nice to Thomas Gounet and several other friends in Paris, dated 6 May 1831 (CG no. 223). He then pursued the journey to Rome on land via Florence. The same chapter of the Memoirs describes the final stage of the journey and the arrival in Rome through the Piazza del Popolo.

The Académie de France, in the Villa Medici in Rome, was Berlioz’s base during his stay in Italy in 1831-1832, as it was for his fellow Prix de Rome laureates. He describes it thus (Memoirs, chapter 32):

The villa Medici, where the boarders and the director of the Académie de France live, was built in 1557 by Annibal Lippi; Michelangelo subsequently added a wing and other improvements. It is located on that part of the Monte Pincio which overlooks the city of Rome, from where one can enjoy one of the most beautiful views in the world.

To the right stretches the Pincio avenue [now the Viale della Trinitá dei Monti]; it is the Champs-Élysées of Rome. Every day, when the heat begins to abate, it is flooded with pedestrians, horse-riders and especially open carriages, which for a while bring to life this magnificent but deserted plateau, but at the stroke of seven they all hurriedly go down to the city and disperse like a swarm of flies swept away by the wind.

To the left of the villa, the Pincio avenue leads to the little square of Trinità del Monte which is graced by an obelisk, from which a large flight of marble steps descends into Rome and serves as a direct communication link between the top of the hill and the Piazza di Spagna.

On the opposite side the palace opens up on fine gardens designed in the style of Lenôtre, as you would expect from the gardens of any self-respecting academy. They comprise a wood of laurel and oak trees rising on a terrace, bounded on one side by the walls of Rome, and on the other by the convent of the French Ursulines which adjoins the ground of the villa Medici.

Opposite, in the midst of the uncultivated fields of the villa Borghese, one notices the miserable and abandoned country house where Raphaël used to live; a further touch of gloom is added to this melancholy landscape by a ring of pine trees which bounds the horizon and is permanently covered by a black swarm of crows.

Such in summary is the setting of the truly royal dwelling which the munificence of the French government has provided to its artists for the duration of their stay in Rome. The director’s quarters are astonishingly lavish; many an ambassador would be happy to have their equivalent. On the other hand the rooms of the boarders, except for two or three, are small, uncomfortable and especially very badly furnished. I bet that from this point of view a sergeant at the Popincourt barracks in Paris is better off than I was at the palace of the Accademia di Francia.

[…] The boarders are admittedly required to send every year to the Academy in Paris a painting, drawing, medallion or a score, but once this task has been completed they can spend their time as they please, or even fail altogether to spend it profitably, and nobody takes any notice.

Berlioz fulfilled the letter, if not the spirit, of this requirement: from Rome he sent to the Institut de France in Paris the overture Rob Roy, the Quartetto e coro dei maggi (which was coolly received), and the Resurrexit from his 1825 Messe solennelle. As he recalls in his Memoirs (chapter 39), the academicians did not even notice that this score was old material and had already been performed in Paris at Saint-Roch and Saint-Eustache years before Berlioz won the Prix de Rome and went to Italy.

From his base at the villa Medici Berlioz was able to visit the famous sights of Rome, such as St Peter’s or the Colosseum. But he did not enjoy his stay in Rome, as his correspondence repeatedly shows (see for example CG nos. 232, 236, 240, 241, 244), and in his later recollections he did not disguise the fact (Memoirs, chapter 36):

[…] When you add to that the oppressive influence of the Sirocco, my overwhelming and ever present thirst for enjoying music, painful memories, the disappointment of being exiled for two years from the musical world, an inexplicable but very real inability to work at the Academy, and it will be understood how intense was the spleen that was devouring me. I was aggressive like a chained dog. […]

In principle Berlioz was required to spend two years in Italy; in practice he stayed no more than 15 months in all, less than half of which was spent in Rome. Not long before he finally left Rome, he wrote to Spontini in Berlin: ‘I have hardly ever spent more than two consecutive months in Rome; I was constantly off to Florence, Genoa, Nice, Naples, the mountains, on foot, with the sole aim of wearing myself out to the point of numbness and being able to endure more easily the spleen that was tormenting me’ (CG no. 268, 29 March 1832). After first reaching Rome around 10 March 1831 he left after 3 weeks to head for Florence, then spent a month in Nice and was only back in Rome on 3 June. Within a fortnight he was off to Tivoli then Subiaco and only returned to Rome around 25 July. He stayed in Rome over the summer, partly through lack of funds and partly because of the heat; there is also a gap in his correspondence between 7 August and 14 September. In September Berlioz returned to Subiaco, then at the end of the month was off to Naples, from which he returned only near the end of October. He revisited Tivoli and Subiaco in November, and it was only at the end of the month that he settled in Rome for the winter, though by February he resumed his excursions to Subiaco and the vicinity of Rome, and by mid-March he had decided to leave Rome finally in early May (CG nos. 265, 266, 267).

![]()

Berlioz was uncomfortable at the Villa Medici: he constantly referred to it as the ‘stupid barracks’ (CG nos. 231, 234, 249, 266, 267, 270). Yet the atmosphere at the Académie was free and relaxed, not least thanks to the hospitality and understanding of the director Horace Vernet and his family: his father Carle, his wife, and his daughter Louise. ‘[His] relations with us were those of an excellent comrade rather than a stern director’ Berlioz wrote of him later (Memoirs, chapter 36), and Vernet showed throughout the greatest indulgence to his rather recalcitrant student, notably at the time of the escapade to Nice (cf. CG no. 217). In 1832 he was prepared to turn a blind eye to Berlioz’s premature departure from Rome, on condition that he did not appear in Paris before the end of the year, though it should be mentioned that Berlioz had seriously toyed with the idea of leaving without informing the director of his exact whereabouts (CG nos. 249, 255, 261). A few years later, in 1835, Berlioz dedicated to Vernet his cantata Le Cinq Mai, part of which was composed in Rome, as emerges from a later feuilleton of Berlioz (Journal des Débats, 23 July 1861, reproduced in À Travers chants).

In a letter to his sister Nancy, Berlioz gives a sketch of Horace Vernet (CG no. 224, 9 May 1831, from Nice):

[…] He is a short man, slim, elegant in appearance, obliging but sensitive, a respectful son, who loves his daughter like a brother, and his wife like an uncle, who makes 20,000 francs in 8 days, draws the pistol and the sword like Saint-Georges, a superb drummer who when he dances the tarantella with his daughter brings the whole salon down; stiff and dry, good-natured and frank, he loves Gluck and Mozart and detests the Académie. There is much that is good there. [...]

Another letter describes Vernet’s father Carle and gives a glimpse of social life at the Villa Medici (CG no. 232, to his family; 24 June, from Rome):

[…] The evening before last I had for the first time in our convent an experience that truly moved me. There were four or five of us sitting by moonlight around the fountain on the little staircase which leads to the gardens; lots were drawn for someone to fetch my guitar, and as the audience consisted of the small number of pensioners that I can tolerate I did not need any prompting to sing. As I was starting an aria from Iphigénie en Tauride, M. Carle Vernet arrived, and within two minutes he started sobbing and burst into tears; unable to bear it he fled to his son’s sitting room, shouting in a choking voice: « Horace! Horace, come! — What is it, what is it? — We are all crying! — How come, how come, what’s happened? — It is M. Berlioz who is singing Gluck for us; yes, monsieur, as you say, it makes you want to fall on your knees (he said to me). Come, you are a melancholy character, I understand you, I do, there are people who… » — He didn’t finish, yet nobody laughed. […] This evening is our director’s birthday, there is going to be a large ball, and old Carle is going to corner me once more to talk about Gluck; he is so happy that I am not like my predecessor who found all this rather old-fashioned! He is an unusual man, who spends half of the day riding (he no longer paints) and the rest of the time making puns and worrying about his son’s health, whom he loves with an intensity that is unusual with old men. […]

At first Berlioz was not impressed with Louise Vernet’s voice: ‘I would rather listen to the Lesueur ladies or the scream of a bat than to hear her sing’ he wrote (CG no. 232), but both Louise Vernet and her mother became very fond of Berlioz. Ernest Legouvé, who visited the Villa Medici not long after Berlioz’s visit, wrote in his memoirs: ‘Berlioz had recently departed, leaving the memory of a clever but eccentric man who took delight in being odd, and he was frequently described as a poseur. Mme Vernet and her daughter spoke up for him and extolled his merits; women have more insight than we do in sensing men of superior ability’ (Soixante ans de souvenirs, chapter 16). Shortly after leaving Rome and now in Florence Berlioz wrote to Ferdinand Hiller (CG no. 270, 13 May 1832):

[…] I would spend all my evenings with M. Horace, whose family I like very much, and who on my departure lavished on me proofs of friendship and affection, which moved me all the more as I was hardly expecting them. Mlle Vernet is prettier than ever, and her father ever more like a young man. […]

Back in La Côte-Saint-André in July 1832 Berlioz was already feeling nostalgic, as he wrote to Mme Vernet (CG no. 282):

[…] I am suffocating through lack of music; in the evenings I can no longer look forward to Mlle Louise’s piano, nor the sublime adagios that she was kind enough to play to me; my insistence that she should keep repeating them could not affect her patience or the expressiveness of her playing. […] I would have liked to send Mlle Louise some small composition of the kind that she likes, but what I had written did not seem worthy of raising an appreciative smile from the graceful Ariel, so I followed the prompting of my self-esteem and burnt it. […]

It was Louise Vernet who gave at the Villa Medici the first performance of the melody La Captive which Berlioz had written in Subiaco in February 1832, and he dedicated to her an early version of the song.

![]()

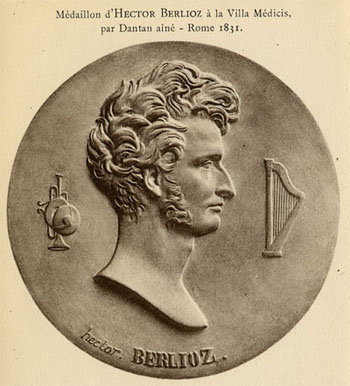

When he arrived for the first time at the Villa Medici in March 1831 Berlioz’s initial impressions of his companions were favourable: ‘All my comrades who were expecting me received me with the utmost cordiality’ (CG no. 223, 6 May). But when he returned from Nice in June he quickly became impatient: ‘I am surrounded in my stupid barracks with vulgar beings, devoid of artistic feelings, whose company and buzzing annoy me terribly; there are two or three notable exceptions, but that is all’ (CG no. 231, 14 June). Then a fortnight later: ‘I need to be alone again; I notice that these gentlemen of the Académie, with whom I share very little in common, are eyeing me askance and control everything I do; if I do not want to appear mannered (their word) I have to adapt to their manners and way of feeling, seeing and talking […] in a word, I need to be someone else than myself’ (CG no. 233, 3 July). Yet once out of Rome Berlioz had no difficulty in making friends. In Subiaco he writes: ‘There are several French landscape-painters in the house where I am staying, who have come to make pictures of the beautiful countryside around Subiaco; we dine together, and one of them is a friend from the Académie’ (CG no. 236, 10 July). His name was Jean-Baptiste Gibert, about whom Berlioz wrote the story of Vincenza which first appeared in 1833 and was later reproduced in the Soirées de l’orchestre. Another painter who resided at Subiaco was Isidore Flacheron, who married a local Italian girl and settled later in Lyon, where Berlioz saw him again in 1845 (Memoirs, chapters 37, 38, 41; CG no. 987). In October 1831 Berlioz made the trip to Naples in the company of the architect Dufeu and the sculptor Dantan; the latter made a medallion of Berlioz in Rome in 1831.

Among the laureates at the Villa Medici the architect Joseph-Louis Duc became closest to Berlioz, who introduced him to the music of Beethoven. When Duc eventually left for Paris Berlioz gave him a letter of introduction to an administrator at the Conservatoire: ‘[Duc] is very keen to hear the works of Beethoven, and on my recommendation he hopes that you will make it easy for him in case it is still as difficult to obtain tickets. He is a real gentlemen’ (CG no. 239, 14 September 1831). It emerges from another letter a few days later (CG no. 241) that Berlioz entrusted Duc with a confidential parcel and a sensitive mission, viz. to return to Camille Moke a number of presents and letters she had sent to Berlioz. In later years Duc and Berlioz remained good friends. While in London in 1848 Berlioz dedicated to him an arrangement of the Apothéose of the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale (CG no. 1200), and in 1852 he jokingly attributed to an imaginary composer ‘Pierre Ducré’ the chorus Farewell of the shepherds to the Holy Family from l’Enfance du Christ that he had improvised one evening at Duc’s flat in Paris (the story is told in detail in the Grotesques de la musique).

Berlioz was keen to return to Paris, but as the moment of departure approached he began to see Rome in a different light. On 20 March 1832 he wrote to his mother (CG no. 266):

[…] I am counting the days that I still have to spend in these stupid barracks. I will be glad to revisit Rome for her sublime plains and enchanting mountains, but then I will be a free person which I am not at the moment, and an enforced absence will not be making me sick through lack of music. On the contrary I will come to relax here, as in a beautiful garden, which I will appreciate much better. […]

But Berlioz never returned to Rome or to Italy.

![]()

Unless otherwise specified, all the modern photos reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in May 2007; other pictures have been scanned from engravings, postcards and other publications in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

One of the by-products of Berlioz’s stay in Rome were the first genuine portraits of himself. He refers to this in the letter of 6 May 1831 from Nice mentioned above (CG no. 223):

[…] Talking of lithographs, I have had my portrait done in Rome; it is no good; but a sculptor has done my medallion, and it is a very good likeness, in a half-size plaster. […]

The portrait, probably by Émile Signol, in fact was apparently not completed till the following year in late April (CG no. 269).

This portrait is in the Académie de France, Villa Medici. It was on display at the Bibliothèque nationale de France special exhibition in 2003 marking the bicentenary of Berlioz’s birth, and wasy on display at the ‘Berlioz and Italy Exhibition’ held at the Hector Berlioz Museum (30 June-31 December 2012).

The original copy of the following 5 engravings have been donated by us to the Hector Berlioz Museum and they hold copyright for them.

The above engraving was published in the Illustrated London News, 4 May 1850.

This painting, entitled The Fountain of the Académie de France, Rome, with St Peter’s in the distance, is by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. It is in the Municipal Gallery of Art, Dublin, Ireland.

The Villa Medici was extensively refurbished in the 1960s and 1970s under its then director, the painter Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus (1960-1977).

This staircase leads to the gardens and to the offices and pensioners’ rooms.

This could have been the refectory in which Berlioz had dinner with his fellow pensioners.

Saint Peter’s can be seen in the distance.

The original obelisk was taken to Florence in 1764-1788. Joseph Suvée (1792-1807), director of the Académie, replaced it with a statue of Venus, which remained in place until 1960. In 1961, the then director Balthus, had the statue replaced with a resin replica of the original obelisk.

In the evenings, after the usual drinks at the Caffè Greco, Berlioz and his fellow pensioners would sometimes gather on this terrace and sing opera arias, as Berlioz recalls in the Memoirs (chapter 36):

Those who returned virtuously to the barracks of the Académie [sc. after visiting the Caffè Greco] would sometimes gather under the great vestibule which overlooks the gardens. Whenever I was there, my poor voice and miserable guitar were called upon. We would all sit around the little fountain which falls back into a marble basin and refreshes this echoing portico, and sing by moonlight the dreamy melodies of Der Freischütz and Oberon, the vigorous choruses from Euryanthe, or entire acts of Iphigénie en Tauride, la Vestale or Don Giovanni; for I must say, to the credit of my companions at the Académie, that their musical tastes were anything but vulgar.

A letter to his family dated 24 June 1831 gives a first hand report of such an evening (CG no. 232, cited above).

The gardens have many alleyways, at the end of some of which there is a statue on a marble pedestal, like the one shown in the above photo. These statues were installed in the 1960s as part of Balthus’s great project of restoration of the Villa Medici.

Saint Peter’s can be seen on the right.

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.