![]()

![]()

Berlioz in Pesth

Illustrations

This page is also available in French

![]()

Pesth had been on Berlioz’s projected itinerary at the very start of his first trip to Germany in December 1842. On December 9, on the eve of his departure, he wrote to his sister Nancy of his plans for concerts in Brussels, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Munich, and added (Correspondance génerale no. 791, hereafter CG for short):

The rest is not yet fixed, but from Munich I shall go on to Vienna and then Berlin, Leipzig, Hanover, Pesth, Brunswick, Dresden, Hamburg, and if possible to Amsterdam on the way back.

In practice the whole itinerary and timing had to be drastically changed, and the eventual trip was very different from what had originally been planned. Berlioz did not visit Pesth till February 1846 in the course of his second major trip to Germany, as a sequel to his long stay in Vienna.

Pesth, like many cities in Germany and central Europe, had numerous musical links with Paris, which at the time was regarded as the centre of the European musical world. The leader of the orchestra of the National Theatre at Pesth, Kohne, had studied at the Conservatoire (Memoirs, Travels to Germany II, 3rd Letter). Several Hungarian musicians were active in Paris and they could have informed Berlioz of musical conditions there. Apart from Liszt, there was the pianist and composer Stephen Heller (1813-1888), a native of Pesth who had settled in Paris in 1838 and joined the circle of Berlioz’s close friends soon after his arrival. He remained there till the composer’s death and was particularly close to him in his later years. A decade after the death of Berlioz he wrote an article of reminiscences on the composer.

Though different in temperament and sometimes in outlook – Heller was quiet and undemonstrative – the two men quickly developed a mutual esteem on both personal and musical levels. Heller praised the Symphonie fantastique after a concert at the Conservatoire on 25 November 1838 in an article in the Revue et Gazette Musicale (2 December; cf. CG no. 593). Berlioz reciprocated; in a letter to Liszt (CG no. 660, 6 August 1839) he says of Heller:

He is serious, has talent, a vast musical intelligence, a quick grasp, and as a performer shows great fluency: these are the qualities that those who know him well agree he possesses, and I am one of those.

In his articles Berlioz often praised Heller’s piano music (for a fuller collection of references see the detailed entry on him on this site). On 30 January 1842, for example he reviewed Heller’s Caprice symphonique for piano in the Journal des Débats (Critique musicale V pp. 32-3):

The inspiration of this pianist-composer is always powerful, his style elevated and vigorous, his forms as simple as they are original […] Since Beethoven’s sonatas, nothing more completely elevated and beautiful has been written in this genre […] With his Caprice symphonique M. Heller has evidently raised himself to the front rank of composers of piano music.

Years later, Berlioz included in À Travers Chants, at the end of an article on Henri Reber, a short but eloquent paragraph in praise of Heller and his piano music. In the final section of the Memoirs he describes a meeting in September 1864:

As tended to happen at that time of the year almost all my friends had left Paris. Alone to have stayed behind was Stephen Heller, that charming and witty man, a well-read musician who has written such a large number of wonderful pieces for the piano. His melancholy spirit and religious devotion for the true gods of art have a powerful attraction for me.

When Berlioz, in Prague at the time, was about to set off for Pesth early in 1846, he naturally thought of Heller (CG no. 1017; to Joseph d’Ortigue, 27 January):

Now I am about to leave once more my beloved Viennese and go and visit the compatriots of [Stephen] Heller. Please go and see him on my behalf and show him this letter; it will be as though I am writing to him. I ought to write to him at length in return for all the kindness he has so often displayed to me; I will do this one of these days before I leave Pesth.

There are however no extant letters from Berlioz to Heller dating from the stay in Pesth, and there is nothing to suggest that it was Heller specifically who had suggested the trip on that occasion.

The projected trip to Pesth is only first mentioned in letters of late January and early February 1846 (CG nos. 1016bis, 1017, 1018-19). But it had evidently been planned by Berlioz during his long stay in Vienna from November 1845. The Wiener Allgemeine Musikzeitung (hereafter WAM for short) reported on 20 November that Berlioz was intending to go to Pesth and Prague after his stay in Vienna (the visit to Prague came in practice first, in the second half of January 1846). It is likely that the invitation to Pesth had come from Count von Ráday, the superintendent of the National Theatre there, as reported in December by the German-language paper Der Schmetterling, published in Pesth (on all this cf. Haraszti, pp. 49-50, 52). Ráday is mentioned by Berlioz in the Memoirs as having been of great assistance to him during his stay there (Second Trip to Germany, Third Letter). The projected visit to Hungary was public knowledge in Vienna at the time: on 5 January 1846 a poem in honour of Berlioz by the Viennese writer Johann Hofzinser was published in the journal Der Wanderer, and it explicitly looks forward to Berlioz’s forthcoming trip to the ‘wonderland of the fiery Magyars’.

The third letter in Berlioz’s Travels to Germany II is devoted to the visit to Pesth, and concentrates on the celebrated story of the composition and first performance of the Rákóczy March. The story as told by Berlioz is substantially accurate and can be supported and supplemented by contemporary evidence (cf. Haraszti, pp. 50-55 for what follows). It is likely that Berlioz first heard the Rákóczy march during his stay in Vienna, as played by gipsy bands; he also heard it in Pesth. Earlier in 1845 he had orchestrated and developed Léopold von Meyer’s Marche Marocaine, which he performed at a concert in Vienna on 23 November (cf. CG no. 1006, to Meyer). This may have provided the blueprint for his treatment of the Rákóczy march. Berlioz states that the march was written ‘the night before he left for Hungary’. In practice, work on it was continued during the stay in Pesth, and the local press writes of it as having been written on the spot (Haraszti p. 63).

Berlioz left Vienna for Pesth on 6 February (CG no. 1019; the WAM gives the date of departure as 7th February) and was accompanied by Marie Recio (this emerges from CG no. 1020bis). The journey should have been by boat down the Danube, but the river was in full flood and Berlioz travelled instead by stagecoach across the plain. The Memoirs give a vivid account of the journey: the driver lost his way and ended up in the bed of the river, where all the passengers nearly drowned during the night… The next day they managed to reach Buda on the other side of Pesth and Berlioz crossed the river in a small boat. On arrival, where his visit was keenly expected, Berlioz busied himself with the usual preparations for gathering and rehearsing an orchestra, but soon found himself caught up in the ferment of national animosities that was to give his visit such impact. The orchestra of the National Theatre, where he proposed to give his concerts, was short of players but there was a strict ban on inviting musicians from the rival German Theatre, and use of the German language at the National Theatre was altogether prohibited... The problems of recruitment were eventually settled, but as Berlioz observed tartly at the start of his account:

[…] Some disgruntled souls pretend that Pesth is in Hungary and that Prague is in Bohemia, but these two states are nevertheless an integral part of the Austrian empire to which their bodies, souls and possessions are wholly dedicated, rather like Ireland is devoted to England, Poland to Russia, Algeria to France, just as all conquered peoples have from time immemorial been attached to their conquerors.

The account in the Memoirs concentrates on the story of the performance of the Rákóczy March. The overwhelming impact of the march is corroborated by reactions in the contemporary press (Haraszti, pp. 60-3) and by the evidence from Berlioz’s correspondence at the time. On 15th February, the day of the first concert, Berlioz writes to Dr Ambros in Prague (CG no. 1021):

I have stirred the passions of the masses through a Hungarian theme (the Rákóczy march) which I have orchestrated and developed. You cannot imagine this hall in eruption, the furious shouting of all these men, the Elien, the gesticulating… There is in particular a passage where over a long crescendo the theme returns in a fugato between basses and violins, with piano strokes on the bass drum imitating cannon shots, which made them go wild.

Similarly to his sister Nancy, writing from Breslau and Prague over a month later (CG no. 1029):

I am back from the depths of Hungary where I had more success than I had hoped. I will tell you in my feuilletons in Les Débats the impact of my music on these almost primitive souls on the banks of the Danube. They have been moved to fury when I had the idea of writing for them a triumphal march on one of their national themes. It was a terrifying spectacle to see these men roused to delirium in their hatred of Germany which the innocent allusions of my orchestra awakened in them.

Berlioz’s account in the Memoirs gives no further details about his concerts in Pesth. In practice he gave two concerts, on 15 (CG no. 1021) and 20 February (CG no. 1023), both with an almost identical programme. It comprised the Roman Carnival overture, the three middle movements of the Symphonie fantastique, the Pilgrim’s March (2nd movement) from Harold en Italie, the song le Chasseur danois at the first concert, while at the second le Jeune pâtre breton and the bolero Zaïde were substituted. Both concerts ended, appropriately, with the Rákóczy March. The March created a sensation, but the rest of the music was well received – several pieces were encored at the first concert (CG no. 1021).

During his stay in Pesth Berlioz also managed to continue the composition of the Damnation of Faust which he had started several months earlier. ‘In Pesth, one evening when I had lost my way in the city, I wrote the choral refrain of the Ronde des paysans [in Part I] by the gaslight of a shop’, he relates in his Memoirs (chapter 54). In the same chapter he tells how the extraordinary success of the march in Pesth led him to bring Faust to Hungary at the start of the work and to introduce the march at the end of Part I. What had started life as the Rákóczy March thus became the Hungarian March.

Berlioz also had time to study the musical scene in Pesth: he had particular praise for the composer Ferenc Erkel after hearing a performance of one of his operas at the National Theatre. He was also privileged to attend two balls reserved to the Hungarian nobility. He relates a month later to his sister Nancy (CG no. 1029):

I can assure you that this nomadic life, stressful as it may be at times, is nevertheless highly stimulating – from an artistic point of view, obviously, but also through the insights it allows me into the different social contexts where I find myself introduced. In Pesth in particular, at those great Hungarian balls to which only noble Hungarians were admitted, and where they only performed national dances on national themes played by the Zingari, I have been struck with altogether novel impressions. The Hungarians are a people so different from others, and so naïvely proud!

Berlioz’s original intention had been to depart immediately after his second concert on 20 February (CG no. 1021), though he may have stayed on a few days longer. At any rate he was back in Vienna by the 25th or earlier (CG no. 1025bis; the WAM of 24 February reports that he was back on the 22nd): in the meantime the Danube had subsided and the journey home by the river was uneventful.

Though Berlioz never returned to Pesth the impact of his visit and of the Hungarian March was lasting. On his return to Vienna he found the Austrian authorities alarmed at the ferment that had been stirred up among the Hungarians. They subsequently sought to ban public performances of the march, though not altogether successfully (Haraszti p. 87): as a result of Berlioz’s visit the march had become even more of a national symbol than it already was.

As he mentions in his Memoirs, Berlioz left behind his autograph score of the march, a copy of which was sent to him in Breslau a month later. On the basis of this autograph an arrangement for piano was published in 1860 by Antal Zapf, professor at the Conservatoire in Pesth. This came as a shock to Berlioz: he had not authorised any such arrangement and, as mentioned in the Memoirs, ‘I have since then made several changes in the orchestration of this piece, adding to the coda some 30 extra bars of music which I believe add to its effectiveness’. This he had to point out years later to the conductor Ferenc Erkel who had notified Berlioz of the arrangement (CG no. 2469, 25 January 1860). In practice the Hungarians did not hear the final version of the march till 1890 when the complete Damnation of Faust was first performed in Pesth (Haraszti p. 87).

In the same chapter of the Memoirs Berlioz relates how in 1861 the youth of Györ in Hungary (Raab in German) sent him a silver crown accompanied by a moving letter in which they thanked him for writing the now famous march on their national theme (CG no. 2531, 31 January 1861). This was prompted by a performance of the march that had been sponsored by a young admirer of Berlioz, Rose de Szuk-Matlekovits, who was later to pay a visit to Berlioz in Paris in February 1866 (Haraszti pp. 87-8, 96-7). The letter was soon published in the Revue et Gazette Musicale, and Berlioz cites in the Memoirs his own response to it. It is appropriate that the silver crown offered by the Hungarians should have been one of the objects displayed at Berlioz’s funeral on 11 March 1869 (Haraszti p. 106). The crown is now in the Musée Hector Berlioz at La Côte Saint-André.

See also the page Berlioz’s concerts in February 1846

_________________________

![]() References in this page to ‘Haraszti’ are to the book by Émile Haraszti, Berlioz et la Marche Hongroise (Paris, 1946), a copy of which is in our collection

References in this page to ‘Haraszti’ are to the book by Émile Haraszti, Berlioz et la Marche Hongroise (Paris, 1946), a copy of which is in our collection ![]()

![]()

Unless otherwise stated all the pictures have been scanned from documents and publications in our own collection. © Monir Tayeb et Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction are reserved.

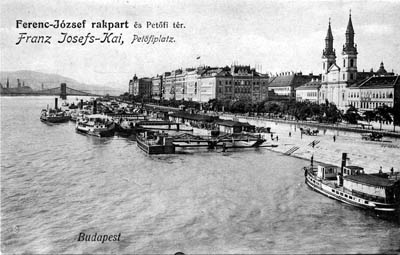

This early 20th century postcard is from our collection.

The theatre, built in 1837 as ‘Pesti Magyar Színház’ [Hungarian Theatre Pesth] by Mátyás Zitterbarth, was opened on 22 August 1837. In 1840 it was nationalised and renamed Nemzeti Színház, and was rebuilt in 1875. The building was closed in 1908 and demolished in 1914. The above lithograph is by F X Sandman, after Rudolph Alt.

A copy of this lithograph is in the Budapesti Történeti Múzeum.

The following two pictures are from the book by Émile Haraszti referred to above, in our collection.

![]()

The Berlioz in Pesth page was created on 1 September 2005; enlarged on 1 October 2005. Revised on 1 February 2024.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb