![]()

Unless otherwise stated all pictures on Berlioz Photos page have been scanned from engravings, paintings, postcards and other publications in our own collection. All rights of reproduction reserved.

This page includes portraits or photographs of the following composers: Beethoven, Gluck, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Spontini, and Weber. Of thse the first two and the last two enjoyed a special status for Berlioz. In his Memoirs (Post-Scriptum) when outlining his musical creed he states that he ‘belongs to the religion of Beethoven, Weber, Gluck, and Spontini’.

![]()

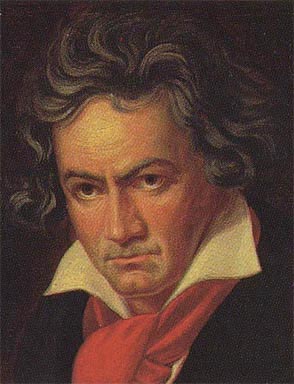

The original copy of this portrait by Joseph Stieler, dated 1819, is in the Beethoven House in Bonn.

Among the composers Berlioz admired most, Beethoven was the last one he discovered, late in 1827 and early in 1828; once discovered Beethoven went straight to the top of Berlioz’s musical Pantheon, though without displacing completely Berlioz’s first idol Gluck. A major part in this discovery were the concerts given by the newly founded Société des concerts du Conservatoire under its director François Habeneck, as Berlioz acknowledged in his Memoirs (chapter 20). Thereafter Berlioz wrote extensively about Beethoven’s music in the 1830s; he collected his articles on the Beethoven symphonies first in his Voyage musical of 1844, then again definitively in À Travers chants in 1862 where the essays on Beethoven — the symphonies, the chamber music, and the opera Fidelio — are given pride of place after the introductory chapter on music, and ahead of the chapters on Gluck. An English translation of Berlioz’s essays on Beethoven’ symphonies (by Michel Austin) is available on this site. For a detailed discussion of the impact of Beethoven on Berlioz see the page Berlioz and Beethoven. (See also Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven.)

The above picture appeared in L’Illustration of 9 August 1845.

Beethoven’s statue in Boon was inaugurated in August 1845 in a ceremony that had been instigated by Liszt and to which leading musicians from all over Europe were invited. Berlioz attended the inauguration celebrations held on 10-12 August and wrote a report on it in the Journal des Débats of 22 August and 3 September 1849, which was later incorporated in the 2nd Epilogue of the Soirées de l’orchestre (1852).

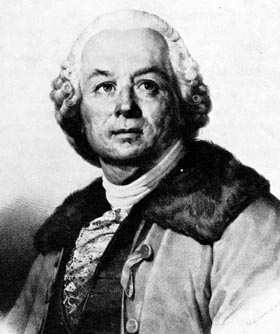

The original copy of the lithograph by Maurin is in the library of the Paris Opera.

As a young man Berlioz admired Gluck even before he had heard a single note of his music: he relates in his Memoirs (chapter 4) how his imagination was fired by reading the articles on Gluck and Haydn in Michaud’s Biographie universelle in his father’s library. His dreams then turned into a reality when he went to Paris and from late 1821 onwards was able to attend performances of Gluck’s works at the Opéra. The early sections of the Memoirs vividly convey his enthusiasm at discovering Gluck (chapters 9, 14, 15). Thereafter promoting the music of Gluck through writing and performance remained for Berlioz a life-long mission; even though he acknowledged that Beethoven was the greater musician, he remained reluctant to place Gluck beneath him (CG no. 2080). He devoted numerous articles to Gluck, a number of which he reproduced later in À Travers chants. In his last concert tour to Russia in 1867-8 he made a point of including in his programmes a large number of works of Gluck. For a fuller discussion of all this see the page on Berlioz and Gluck.

The above portrait was painted by Eduard Magnus in 1845. The original copy is in the Mendelssohn-Archiv, Berlin.

Berlioz first met Mendelssohn in Rome in March 1831 and had frequent contacts with him over the following months, until Mendelssohn left the country in September of the same year. Despite the great differences in temperament and outlook between the two men, Berlioz formed a very positive impression of Mendelssohn’s talent and subsequently never departed from this view. He met him again in Leipzig in January and February 1843 where Mendelssohn was director of the Gewandhaus orchestra and had invited Berlioz to give concerts there. According to Berlioz, Mendelssohn was invariably helpful during his stay. He never saw Mendelssohn again afterwards but remained in touch, and was greatly saddened by the news of Mendelssohn’s death on 4 November 1847. He received the news on the day he arrived in London, where he found that Mendelssohn enjoyed a high reputation with which he fully agreed: ‘I knew him very well […] even had he been a total stranger to me I would mourn him as a great artist and a mind of exceptional distinction’, he wrote not long after (CG no. 1139). It is sad to note that Mendelssohn on his side did not have such a high estimate of Berlioz, as Berlioz found out many years later. Mendelssohn, it seems, was unable to recognise Berlioz’s originality and genius, which may well have exceeded his own very considerable talent.

The above lithograph is by Ed. Lehmann after a painting by Lange.

On his own admission Berlioz was a relatively late convert to the genius of Mozart (Memoirs chapter 17). In the 1820s, he writes, he tended to assimilate Mozart’s operas to those of the Italian school, whose growing popularity threatened the supremacy of his idols Gluck and Spontini; he also took exception to the florid vocal writing of some arias in Mozart operas. But in time ‘the wonderful beauty of his quartets, quintets and some of his sonatas were the first to bring me back to the cult of this angelic genius, the purity of which had alone been sullied in a few places by his association with the Italians and the professors of conterpoint’. Thereafter, and with a few reservations, Berlioz was a devotee of Mozart, especially of the operas Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro and The Magic Flute, and his feuilletons abound in admiring comments on these and other works, and on Mozart in general. It is therefore rather surprising that in his last collection of essays À Travers chants Berlioz should not have given to Mozart the prominence he gave to Beethoven, Gluck and Weber; he only included one article on a Mozart opera which he did not reckon as one of his best (Il Seraglio). Yet many of his articles on Mozart deserve to be better known; see for example among others Débats 23 June (Mozart as a symphonist compared to Beethoven), 9 August (the Requiem), 2 October (Gluck and Mozart), and 15 November 1835 (Don Giovanni); 1 May 1836 (mutilation of Mozart’s operas); 27 March 1849 (Idomeneo, and Oulibischeff the biographer of Mozart); 12 August 1851 (The Magic Flute); 7 January 1853 (The Marriage of Figaro).

The portrait shows the young Spontini and is from a postcard in our collection.

Berlioz’s discovery of Spontini followed immediately that of Gluck at the Paris Opéra in the early 1820s; the very first article Berlioz wrote, in 1823, was devoted to Spontini’s La Vestale, a work Berlioz regarded as its author’s masterpiece and for which he later continued to have a high regard. He saw Spontini as a continuator of Gluck and frequently bracketed the two composers together as objects of his admiration (Memoirs chapters 14, 16, 17). Thereafter Spontini remained one of the composers he admired most, though not on the same level as Gluck or indeed Beethoven. But whereas with Beethoven and Weber, his older contemporaries, Berlioz never met them, in the case of Spontini he started to correspond with him in 1830 and eventually became close to him, particularly in the last ten years of his life when Spontini had settled in Paris. Personal loyalty to Spontini was added to admiration for his music, and may have affected Berlioz’s judgement on him as a composer. Berlioz was very affected by Spontini’s death in 1851 (CG no. 1379) and wrote a generous obituary, which was reproduced the following year in les Soirées de l’orchestre, where Spontini is almost a central figure (see the 11th, 12th and 13th evenings). Berlioz’s loyalty to Spontini extended to his widow, with whom he remained in touch till at least 1863. For a fuller discussion see the page on Berlioz and Spontini.

The original copy of this painting by Beckhauer is in a private collection.

Berlioz’s admiration for the music of Weber has a clear starting date: in December 1824 Berlioz first heard Weber’s opera Der Freischütz at the Odeon theatre, and though it was not the original work but a garbled arrangement by Henri Castil-Blaze, he was immediately won over. As he relates in the Memoirs (chapter 16), Weber’s music opened up a new and captivating world of sound, which formed a welcome contrast to the classical operas of Gluck and Spontini that had so far been the main object of his admiration. He later got to know also Weber’s two other major operas, Euryanthe and Oberon, but was only half convinced by Euryanthe (cf. his later review in Débats 8 September 1857), whereas he regarded both other operas as contrasting masterpieces. Weber was for Berlioz a kindred spirit from whom there was much he could learn, notably as regards orchestration, and he became Weber’s most prominent champion in France. He wrote recitatives for a French production of Der Freischütz at the Opéra in 1841 (Memoirs chapter 52) and included articles on both operas (and on a shorter Weber opera, Abu Hassan) in his collection of essays À Travers chants in 1862. See further the page on Berlioz and Weber.

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the texts and images on Berlioz Photo Album pages.

All rights of reproduction reserved.