![]()

Chronology

Introduction

1843

1854

The sequel

This page is also available in French

![]()

1836

By December: Berlioz meets Lipinski in Paris

1843

28 January: Berlioz travels from Weimar to Leipzig

2 February: lightning visit to Dresden from Leipzig and back by train

6 February: Berlioz travels by train from Leipzig to Dresden

10 February: first concert in the theatre

12 February: Berlioz orchestrates the melody Absence for Marie Recio

17 February: second concert in the theatre

19 February: return to Leipzig

12 September: publication in the Journal des Débats of the 5th Letter (Dresden) of the Voyage musical en Allemagne [Musical Travels in Germany]

1853

December: Berlioz accepts an invitation from Dresden to give two concerts the following spring

1854

10 April: Berlioz arrives in Dresden from Brunswick

22 April: first concert in the theatre (the complete Damnation of Faust)

24 April: rehearsal for Romeo and Juliet

25 April: no rehearsal; second concert in the theatre (repeat of the Damnation of Faust)

26-29 April: daily rehearsals

28 April: a sketch of Berlioz conducting is made by one of the musicians present at the rehearsal

29 April: third concert in the theatre, with the overtures to Benvenuto Cellini and Roman Carnival, The Flight to Egypt, and the complete Romeo and Juliet

1 May: fourth concert in the theatre, repeating the programme of the previous concert

3 May: Berlioz departs from Dresden for Weimar

![]() Note: There is some uncertainty over the date of Berlioz’s second concert in Dresden, which is due to inconsistencies in the evidence provided by Berlioz’s correspondence. The letters Correspondance Générale nos. 1748 and 1749 (hereafter CG for short), both dated by Berlioz 26 April and conceivably written one after the other, both state that the concert was taking place in the evening of that same day. Yet the letters CG nos. 1746 and 1747, both written the day after the first concert on (Saturday) 22 April and dated 23 April, state that Baron von Lüttichau, the manager of the theatre, had asked Berlioz to repeat the concert on the following Tuesday, i.e. 25 April. The matter seems clinched by the letter CG no. 1750, written after this concert, which refers to it as having taken place ‘the day before yesterday, Tuesday’ [this letter is dated by Berlioz ‘Wednesday 27 April’ where ‘Wednesday’ can only be a mistake for ‘Thursday’]. The conclusion seems unavoidable that Berlioz misdated both letters CG nos. 1748 and 1749 to the 26th instead of the 25th, and that the second concert did indeed take place on Tuesday 25 April, as originally planned by Baron von Lüttichau.

Note: There is some uncertainty over the date of Berlioz’s second concert in Dresden, which is due to inconsistencies in the evidence provided by Berlioz’s correspondence. The letters Correspondance Générale nos. 1748 and 1749 (hereafter CG for short), both dated by Berlioz 26 April and conceivably written one after the other, both state that the concert was taking place in the evening of that same day. Yet the letters CG nos. 1746 and 1747, both written the day after the first concert on (Saturday) 22 April and dated 23 April, state that Baron von Lüttichau, the manager of the theatre, had asked Berlioz to repeat the concert on the following Tuesday, i.e. 25 April. The matter seems clinched by the letter CG no. 1750, written after this concert, which refers to it as having taken place ‘the day before yesterday, Tuesday’ [this letter is dated by Berlioz ‘Wednesday 27 April’ where ‘Wednesday’ can only be a mistake for ‘Thursday’]. The conclusion seems unavoidable that Berlioz misdated both letters CG nos. 1748 and 1749 to the 26th instead of the 25th, and that the second concert did indeed take place on Tuesday 25 April, as originally planned by Baron von Lüttichau.![]()

![]()

Berlioz’s first contact with Dresden was formed indirectly in Paris in the 1830s through the Polish violonist Karol Lipinski (1790-1861) who was to become Konzertmeister (leader) of the royal Dresden Staatskapelle (orchestra) in 1839. In the Memoirs Berlioz mentions having met Lipinski in Paris prior to his 1842-1843 visit to Germany; the composer’s correspondence shows that the two were acquainted with each other no later than December 1836 (CG nos. 484bis & 485bis, both in vol. VIII). Berlioz was no doubt mindful of the fact that Weber, one of his idols, had once been conductor of the Dresden orchestra (between 1816 and 1826). It was thus natural that Dresden, one of the major musical centres in Germany at the time, should have been on Berlioz’s projected itinerary at the outset when he set out for his first extended tour of Germany in December 1842 (CG no. 791).

![]()

Berlioz’s first visit to Dresden in February 1843 is most fully known from the account he published on 12 September of the same year in the Journal des Débats (Critique musicale V, pp. 297-307; cf. CG no. 849) – the fifth in a series of letters published under the title Voyage musical en Allemagne [Musical Travels in Germany]. It was soon reproduced in the Voyage musical en Allemagne et en Italie of 1844, then later incorporated in the Memoirs virtually unchanged, except for the significant omission of a sentence which named Marie Recio and mentioned her participation in one of the concerts (Critique musicale V, p 299). The composer’s letters, though informative, are less numerous than for the second visit eleven years later.

While in Weimar Berlioz wrote on the same day to Mendelssohn in Leipzig (CG no. 804, 23 January) and to Lipinski in Dresden (CG no. 803): the proximity of the two cities suggested planning visits to both together. In his letter to Lipinski Berlioz started by recalling their previous acquaintance in Paris – they clearly had not been in contact since Lipinski had left Paris; he then went on to outline his present plans and suggest a visit to Dresden to give two concerts. Favourable replies from both Mendelssohn (CG no. 805) and Lipinski gave Berlioz the green light to travel east. On 27 January, the day before his departure for Leipzig, Berlioz wrote again to Lipinski: ‘I have the pleasure of owing to you alone the first approaches made in my favour in your city and I am delighted that I never doubted your goodwill as a fellow artist; this I will never forget’. He made practical suggestions for the programme, promised letters of introduction from Meyerbeer in Berlin to Baron von Lüttichau, the manager of the theatre in Dresden, and the conductor Reissiger, and enclosed a letter of his own to Lüttichau (CG no. 807). In fact Meyerbeer had already been very helpful: two letters of his are extant, both dated 24 January 1843, addressed to leading musicians in Dresden (Reissiger and Winkler) and warmly commending Berlioz to their good offices.

Soon after his arrival in Leipzig Berlioz made a lightning trip by train to Dresden and back (2 February) to see Lipinski and arrange his visit (CG nos. 810, 812). After his first concert in Leipzig he travelled to Dresden on 6 February where he stayed at the ‘Hôtel de France’, the location of which is apparently not known (CG nos. 812, 814). The two weeks he spent in Dresden were extremely busy and stressful, with a total of 8 rehearsals, far more than in Leipzig. Berlioz’s health took the strain, as he related to his father the following month: ‘I paid my toll in sore throats, stomach upsets, obstinate headaches, nothing has been lacking and I have barely recovered; I have been through the hands of doctors in Dresden, Leipzig and Brunswick’ (CG no. 820, 15 March, from Brunswick). But the visit was rewarding. The musical resources of Dresden were more lavish than anything Berlioz found elsewhere in Germany apart from Berlin (and later Vienna). The orchestra was in general of a high standard, though the principal oboe had the annoying habit of adding ornaments to his part, a mannerism Berlioz still remembered over a decade later (cf. CG no. 1714, 28 March 1854, to Lipinski: ‘Do you still have the same principal oboe who played the disgrace notes [‘les notes de désagrement’] so well when I was in Dresden 11 years ago?’). Encouraged by Lipinski who gave Berlioz unstinting support, and fired with emulation towards their colleagues in Leipzig, the players were prepared to work hard to learn music that was unfamiliar to them. On the day of the first concert (10 February), given like all his other Dresden concerts in the Theatre, Berlioz wrote to Ferdinand David in Leipzig (CG no. 814):

[…] The first concert will take place this evening, and all the omens point to a splendid occasion. M. von Lüttichau has increased by one third the price of the seats and the hall is sold out; we were obliged to have four general rehearsals, without counting those for the chorus; I am exhausted, but fortunately everything will go well, I hope. […]

The second concert took place on 17 February; the day after Berlioz wrote to Auguste Morel (CG no. 815):

[…] I have just given here, in the great theatre of Dresden, two magnificent and productive concerts.

The pieces that made the greatest impression were two movements from the Requiem (the Offertorium with the chorus on two notes, and the Sanctus where the solo tenor was sung by the celebrated German tenor Tichatschek), the Funeral Symphony with the double orchestra and chorus, and the Cantata Le Cinq mai on the death of Napoleon, superbly sung by Wächter, an excellent bass singer from the theatre with a very fine musical feeling. Harold in Italy, with Lipinski as solo viola, and the Fantastic Symphony also made quite an impression on the public and the musicians.

The day after the first concert the military bands in Dresden came to wake me up with a serenade, which as you can imagine led to an impressive consumption of glasses of punch. All these people are in an ecstasy of delight which they can only express by squeezing my hands, greeting and embracing me, since I do not know a word of German. […]

Once back in Leipzig Berlioz gave an account of his experiences in Leipzig, Dresden and other cities to Joseph d’Ortigue (CG no. 816, 28 February):

[…] In Dresden we performed twice the Offertorium and Sanctus, once the Fantastic Symphony, once Harold in Italy, the overtures to King Lear and Benvenuto Cellini, the cantata Le Cinq mai (which moved deeply the audience in the stalls), the cavatina from Benvenuto, one of my new melodies which I recently orchestrated, the Romance for violin, two movements from Romeo and Juliet, and (twice) the Apotheosis with the two orchestras and chorus, as we did at the Opéra in Paris before I left. Reissiger was directing the lower orchestra. […]

[…] The finale [from Harold] was played with spirit, though this performance was not on the same level as in Paris; there were too few violins and the trombones are far too decent for this orgy of brigands.

[…] You can also tell Dieppo that I have still to find his equal, and that the trombone-players who attempt the Funeral Oration [of the Funeral Symphony] give me a sore chest, not to mention sore ears. […]

By combining the evidence of the Memoirs with that of the letters it is possible to establish the programme of the two concerts, though the exact sequence in which the pieces were played is uncertain. Included in both concerts were the excerpts from the Requiem, and the last two movements of the Funeral Symphony (though the solo trombone was evidently not of the standard of Dieppo, Berlioz’s favourite trombonist in Paris). The melody referred to in the letter to d’Ortigue must be Absence, sung by Marie Recio (she is not mentioned by name in the relevant letters). Since according to the autograph score it was orchestrated in Dresden on 12 February 1843 (cf. also CG no. 858), the implication of the letter is that the orchestral version received its first performance in Dresden at the second concert on 17 February (and not in Leipzig on 23 February, as stated for example by D. Kern Holoman, Catalogue of the Works of Hector Berlioz [1987], p. 228). The King Lear overture, the Fantastic Symphony, and the cavatina from Cellini (which was sung by Mme Schubert) formed part of the first concert, while the second included the overture to Benvenuto Cellini, Harold in Italy and the Rêverie et caprice (with Lipinski as soloist), the second and third movements of Romeo and Juliet and the cantata Le Cinq Mai. The second concert was an even greater success than the first, where the ‘elegant part of the audience’ which included the King of Saxony himself, frowned on the tumultuous passions of the Fantastic Symphony, though the ‘general public’ was much more receptive.

Busy as he was with the preparation of his concerts, and in spite of moments of ill-health, Berlioz was at the same time alert to other musical activities in Dresden. It was there that he heard for the first time the outstanding English harp-player Parish-Alvars, whom he was to see again not long after in Frankfurt. A letter of recommendation for Parish-Alvars from Berlioz to J.-B. Chélard in Weimar is extant: ‘I give you my word of honour that he is the most prodigious harp-player who has ever lived; he is a phenomenon. Without any doubt the Grand Duke and the Grand Duchess will be thrilled to hear him’ (CG no. 826, 3 April). Berlioz later inserted a mention of Parish-Alvars in the chapter on the harp in his Treatise on Orchestration.

It was also in Dresden that Berlioz had the opportunity to hear for the first time some of the music of Richard Wagner. Coincidentally Wagner had just been appointed assistant conductor to Reissiger, a post he continued to hold till 1849. He and Berlioz had met before in Paris, where Wagner stayed for the first time between 1839 and 1842. Wagner was present at one of the three performances of Romeo and Juliet at the Conservatoire in November and December 1839 (the third on 15 December, according to CG II pp. 510, 607 n. 2, though no evidence is cited). His name appears on a manuscript list of recipients of complimentary tickets for performances of Romeo drawn up by Berlioz himself (reproduced in David Cairns, Berlioz II [1999], plate between pages 212 and 213; cf. p. 193-4). In August 1840 Wagner also heard a concert performance of the Funeral Symphony. Both works made a lasting impression on him, though, as can be seen from an article on Berlioz he published in the Dresdner Abendzeitung in May 1841, Wagner was from the start ambivalent in his public comments on Berlioz: he recognised the genius of his elder colleague, though rather grudgingly, and could never fully share Berlioz’s way of thinking. During his stay in Paris Wagner also wrote a number of articles for the Revue et Gazette Musicale, including one on Beethoven which Berlioz noted favourably (Critique musicale III, p. 402, December 1840) and two on the revival of Der Freyschütz at the Opéra in 1841 for which Berlioz contributed recitatives in French and orchestrated Weber’s Invitation to the Waltz. Berlioz’s first known letter to Wagner, dated 12 October 1841, actually concerns a projected benefit concert for Weber’s widow in which Wagner played the role of intermediary (CG no. 757).

Berlioz’s comments on Wagner and his operas in his letter on Dresden are, despite some reservations, strikingly complimentary. Berlioz praises Wagner for his helpfulness at rehearsals and commends the decision of the King of Saxony to appoint the young master to his post (see also NL no. 814bis). He expresses admiration for Wagner’s boldness in being both librettist and composer of his own operas, unlike all contemporary composers (including at first Berlioz himself): ‘it must be admitted that those capable of achieving successfully and twice this double task, literary and musical, are out of the ordinary’. During his stay Berlioz heard the second part of Rienzi, which the previous October had earned Wagner his first major success, and the whole of the recently completed Flying Dutchman. He commented favourably on two pieces from the former work and noted approvingly the sombre colouring of the latter, though he criticised the author for his excessive use of tremolo: ‘The sustained tremolo is among all orchestral effects the one which most quickly induces weariness on the part of the listener’.

Berlioz’s positive presentation of Wagner was deliberate, as appears from a letter to Lipinski dated 14 September the same year, after Berlioz’s return to Paris (CG no. 849). Commenting on the account of his visit which had appeared two days earlier in the Journal des Débats, Berlioz remarks: ‘You will see on reading my letter about Dresden that I wanted to put to rest the suspicion you raised in connection with Wagner’. Lipinski – no friend of Wagner if we are to believe Wagner’s autobiography (Mein Leben 1 [1911] pp. 301-3) – may have drawn Berlioz’s attention to derogatory remarks by Wagner in an article published in Dresden two days after Berlioz’s arrival… But Berlioz decided to ignore the matter altogether. The subsequent relations of the two main are pursued elsewhere on this site.

From Dresden Berlioz returned to Leipzig two days after his second concert. It was only late in the summer, when he started publishing the series of open letters on his German travels that his thoughts could turn back to Dresden. Coincidentally, while writing to his sister Nancy on 6 or 7 September he was interrupted by a visitor (CG no. 847; cf. 848):

[…] The unwelcome intruder is a Frenchman who has just arrived from Dresden and is bringing me news of the friends I left behind in Saxony. This pained me, I am so keen to go back there, I feel so ill at ease in Paris… the weather is so fine… Dresden is so beautiful… But instead of going there I must after taking my leave of you keep pen in hand to tell the story of my visit to this elegant city. The fact is that my letters are continuing week after week and fortunately they are enjoying success; in particular the 3rd on Weimar caused quite a stir. I have been receiving congratulations for it even from Germany, where three different translations are already appearing. […]

The publication of the account of the visit to Dresden on 12 September prompted Berlioz to write to Lipinski for the first time since his visit the previous February (CG no. 849, referred to above). The letter is notable for its warm and friendly tone:

You can see for a start that I am not calling you Sir. No! No phrases like that between us! Do friends stand on ceremony when writing to each other?… I need not tell you how often I have mentioned your name here in front of those artists who are worthy of hearing it. It is a joy for me to relate to one and all the welcome you gave me!… I will never forget it. Why are you not free to come to France? Only for a fortnight!… […]

Is your son still with you? In any case please convey him my regards. A thousand greetings to monsieur and madame Schubert who were so graciously helpful to me. If you have the opportunity, do not forget either to send my greetings to Baron von Lüttichau.

I wish you had time to write to me in detail about what is going on in Dresden, at the theatre and elsewhere, with a frank account of the state of musical thinking, if they have any thoughts… Here in Paris we have none. […]

It would be another 11 years before Berlioz returned to Dresden.

![]()

When Berlioz returned to Dresden over a decade later, the personnel in place was substantially as before: Baron von Lüttichau, the manager of the theatre; Reissiger, the chief Kapellmeister; Lipinski, the leader of the orchestra; and the same King of Saxony whose interest in music could not be compared with that of his colleague in Hanover. The main change was that Wagner had now left Dresden and had been replaced as assistant conductor by Krebs, with whom Berlioz had had mixed experiences during his visit to Hamburg in 1843.

One major difference with Berlioz’s first visit to Germany was the changes that had taken place in Weimar in the meantime: when Liszt settled there in 1848 as conductor of the orchestra, his aim, with the support of the Grand-Duchess, was to develop Weimar as a centre of progressive music. He staged Wagner’s Tannhaüser in 1849 and Lohengrin in 1850, and in March 1852 Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini – the first performance of the work since its failure in Paris in 1838. Berlioz, in London at the time, was unable to attend, but travelled to Weimar in November to hear two further performances of the work (now extensively modified from the Paris original) and to conduct a concert himself. Among other protégés of Liszt he met in Weimar (cf. CG no. 1538) was the young Hans von Bülow (1830-1894), a recent convert to Berlioz’s music who together with Liszt made changes to Cellini for the November performances, if not earlier. In the next few years he was to be one of the most active supporters of Berlioz in Germany, as his correspondence with Liszt reveals.

While in Leipzig in November 1853 Berlioz had wind of a plan to invite him to Dresden, as emerges from a letter to his sister Adèle (CG no. 1657, 30 November):

[…] After which [sc. the concerts in Leipzig] I am capable of being mad enough to go to Dresden where the rumour of my forthcoming arrival is being spread.

If the King of Saxony was like the King of Hanover, I would not hesitate… But there are so many people in Paris who are trying to do me harm in my absence… And there is my position at the Conservatoire… Well, we shall see. […]

Hans von Bülow was behind the move, though Berlioz was apparently not aware of this. Berlioz soon received a letter of invitation from Lipinski who had himself approached Baron von Lüttichau; Berlioz replied warmly on 5 December and expressed his willingness to come the following spring to perform Faust ‘with the participation of the wonderful orchestra of which you are leader’ (CG no. 1660). Evidently Liszt had even wider ambitions for Berlioz in Dresden: at the beginning of January 1854 he suggested to Berlioz that after the performances of Benvenuto Cellini in Weimar in 1852 the work should also be staged in Dresden. Berlioz responded with delight (CG no. 1690, 15 January):

[…] I cannot tell you how touched I am by the care and devotion you display for my unfortunate opera and how this fills me with admiration. You are someone quite special. I have long known that, but extraordinary happenings like that are so rare that one may even be allowed to be surprised. Yes of course, you have a free hand to decide on the fate of Cellini and I am entirely with you in giving the preference to Dresden. I also share your view that one must start by publishing it in Germany… if this is possible. […]

In the same letter Liszt apparently mentioned to Berlioz in confidence a plan to have him appointed conductor of the Dresden orchestra (in place, that is, of Reissiger); the Paris press got hold of the rumour and Berlioz tried to quash it in an ironical open letter that was published in the Revue et Gazette Musicale on 22 January (CG no. 1692):

[…] Many Paris papers are announcing my forthcoming departure for a city in Germany, where if we are to believe them I will soon be taking up an appointment as Kapellmeister. I can understand how grievous my final departure from Paris must be for many people, and how painful it will have been for them to give credence to this grave news and to put it in circulation.

It would therefore be a pleasure for me to deny it altogether […] But my respect for truth obliges me to make only one correction. The fact is that I am due to leave France, one day, in a few years, but that the musical ensemble of which I have been appointed director is not in Germany. And since everything gets known sooner or later in this devil of a city, I might as well tell you now the place of my future residence: I am director general of the personal concerts of the Queen of the Ovas in Madagascar. The orchestra of Her Ova Majesty is composed of Malayan musicians and of a few from Madagascar of outstanding ability. It is true that they do not like white people, and consequently I will have a great deal to suffer in the initial stages, but for the fact that so many in Europe have made it their job to blacken me. […]

On 24 January he had to explain to Liszt (CG no. 1696):

[…] I fear you may have thought me guilty of some indiscretion in connection with the business in Dresden you told me about. I have not said a word about it to anybody; I imagine it must have been via Belloni [Liszt’s agent] that the Escudier will have picked up some whisper. It is they who divulged the story in la France musicale; hence this silly rumour in the other Paris papers which forced me to write yesterday in the Gazette musicale the letter which you may have read. […]

But the joke evidently misfired, as can be seen from the next letter to Liszt on 11 March (CG no. 1704):

[…] M. von Lüttichau wrote to me recently that he is still counting on me for April 18 or 20. I will therefore go to Dresden at that time, despite a letter from M. Pohl, a very friendly and charming letter, but in which he expresses his fear of formidable opposition on the part of the two Kapellmeister [Reissiger and Krebs] and of the indifference of the public. Besides Meyerbeer has just talked to me about some insulting letter or other which is addressed to me in the Leipzig Gazette; Baron von Donop is also writing to me from Detmold to warn me about another very hostile article in the State Gazette of Berlin in which the author tries to prove that my joke in the Paris Gazette musicale, concerning my appointment with the Queen of the Ovas in Madagascar, is an insulting reference to Germany. So there are many angry feelings in the air at the moment. Tell me what you think about all this. Two months ago a student wrote to me here a letter of the most impertinent absurdity to which I gave the appropriate response.

[…] I am anything but delighted with this trip to Dresden, which in other respects will earn me virtually nothing. […]

There were other, personal reasons for Berlioz’s worries: Harriet Smithson had died on 4 March. Writing to his sister Adèle two days later, Berlioz could not conceal his despondency: ‘And in a month I am off to Germany; I have been invited to Dresden, the manager of the King of Saxony [Baron von Lüttichau] wrote to me yesterday, and they are waiting for me. I have no taste for anything, I care for music and for everything else just as…’ (CG no. 1701).

All the same Berlioz set off to Germany as planned; his first stop was in Hanover, from where he wrote to several correspondents in connection with his trip to Dresden. First to Lipinski about practical arrangements for his two planned concerts (CG no. 1714, 28 March):

[…] It would be better for these two concerts, where the vocal element is so important, to leave the orchestra in its usual place below and have tiers on the stage for the chorus, set out in such a way that the last rows of the choristers are able to see me clearly. This is what we did in Hanover 4 months ago and the result was excellent. […] I am extremely anxious that we should do something exceptionally good in Dresden and I am counting on you to help me achieve this. […]

He also wrote to Liszt on 31 March (CG no. 1717), adding ‘I also hear that M. von Bülow is in Dresden, and I shall be delighted to see him again; I know how highly you regard him, and it is not everywhere that you find sitting on milestones artists of his calibre who are prepared to extend to you the hand of friendship’. Bülow’s letters to Liszt in the last two months of 1853 show how active he had been on the spot in preparing the ground for Berlioz’s visit, and they confirm Berlioz’s reporting of the reception he received. Mindful of the warnings of Pohl (CG no. 1704, above), Berlioz wrote on 1 April to both of the Dresden conductors to conciliate them in advance (CG nos. 1718 to Reissiger and 1721 to Krebs).

From Hanover Berlioz travelled to Brunswick where on 4 April he wrote to his uncle Félix Marmion (CG no. 1726):

[…] From there [sc. Brunswick] I will go finally to Dresden where I am invited by the manager of the King of Saxony to put on two vast concerts, comprising my legend of Faust, Romeo and Juliet and my oratorio on The Flight to Egypt. I do not know the singers I am going to be given; that is the only cause of worry, because the orchestra is excellent. I am going to have some tough rehearsals there, and will have to contend with some sullen hostility on the part of the two Kapellmeister Reissiger and Krebs; they are anything but delighted at my arrival and the reputation I enjoy of being a good conductor. The German papers are doing me a lot of harm in this respect by drawing comparisons between my style of conducting and that of the national Kapellmeister, comparisons that are all the more dangerous for me as they are rather to my advantage. […]

Once he reached Dresden on 10 April – he stayed at the Goldner Engel Hotel [Golden Angel Hotel], the location of which appears not to be known – his worries began to abate. As he wrote to his son Louis on 14 April (CG no. 1733), ‘I find everyone here very well disposed; there are hopes of putting on a great and rich concert. Dresden is a magnificent city, vast and animated like Paris. All my former friends are still here’. On the same day he wrote to Liszt (CG no. 1738): ‘I frequently see M. von Bülow who is a fine and charming gentleman. He has already found so many engraving errors in the score of Faust I brought you that I will take it back to Paris for correcting’. Bülow is mentioned in several other letters during the stay in Dresden (CG nos. 1739, 1740, 1748).

During the week before the first concert Berlioz had serious worries about the state of preparedness of the singers, especially the soloists, who a few days before the concert had not even looked at their parts; on 18 April he wrote an anxious letter to Lipinski on the subject (CG no. 1742, the last preserved letter to him; cf. 1739 to Liszt a few days earlier). In the end all went well. On 23 April, the day after the first concert, he wrote to Liszt (CG no. 1746):

[…] I am very happy to be able to tell you that our Faust scored a great success yesterday. It is in truth the most magnificent performance I have ever obtained of this difficult work. I do regret that you were not able to hear the last two acts which you do not know. The Ride to the Abyss, the Pandaemonium and the Scene of the Will o’ the Wisps made an extraordinary impact. M. von Lüttichau immediately came to tell me that we would be repeating Faust next Tuesday [25 April]. On Saturday [29 April] the announced programme will be performed: it consists of Romeo, the Flight to Egypt and an overture.

M. von Lüttichau has just left me and after numerous compliments he spoke to me these words that are clear enough and coincide with your predictions: « Our orchestra is a particularly fine one, is it not? But it is a pity that it is not conducted as it ought to be; you would be the person to bring it to life. »

I will wait till he speaks more directly. […]

To Liszt again, on 25 April (CG no. 1748; cf. 1749 to Joachim in Hanover, the same same day [both letters are misdated 26 April by Berlioz]):

[…] I am writing to you a few lines today, because every day of this week I will be rehearsing from morning to evening. As we are repeating Faust this evening, we are allowing all our singers and instrumentalists the chance to catch breath. I drove the orchestra rather hard yesterday. At the second attempt, the Queen Mab scherzo went without a hitch from beginning to end. I cannot get over it. This orchestra is wonderful. M. von Lüttichau is more and more gracious. Reissiger is spoiling me, he embraces me, he writes verses for me… which are rather curious. I am told the press is bitter-sweet, more bitter than sweet. I had a visit from M. Banks [Karl Banck, 1809-1889], the influential critic who overwhelmed me with his know-all manner and his patronising cool; apparently he writes Lieder and admires Mozart exclusively. He reportedly grants me a few pieces like the Ride to the Abyss, the chorus of the Sylphs, the [Hungarian] March, and a certain power for contrived effects, but is of the view that I am totally lacking in ideas. We are awaiting the article in the Dresden Constitutional which will appear this evening and is likely to leave me thunderstruck, because the author is an even more exclusive Mozartian than his colleague and he will not accept any of Beethoven’s last compositions, not even those of his second style. I feel like doing like Melle Clauss who went to ask Davison for piano lessons to gain the support of the Times and the Musical World; perhaps these gentlemen would agree to give me a few lessons in composition. Bülow is having a good laugh at all their naïve talk. Fortunately we have the public on our side together with all the musicians who are exceedingly zealous.

[…] We are giving both overtures of Benvenuto at the concert on Saturday [29 April; i.e. the overtures to Benvenuto Cellini and Roman Carnival]. It is an idea of Bülow’s, and I think it is a good one. […]

To Robert Griepenkerl in Brunswick, on 27 April (CG no. 1750):

[…] I am writing you these few lines to inform you that Faust has scored here an extraordinary success with the public and the musicians. After the first performance M. von Lüttichau came to congratulate me on the stage and ask to repeat Faust three days later. It has therefore been performed again Tuesday (the day before yesterday) [25 April] before an audience that was even warmer than on the first day. This Saturday [29 April] we are giving Romeo and Juliet, the Flight to Egypt, and the two overtures to Benvenuto Cellini.

All the musicians are up in arms against an article by M. Banks who claims, like your gentleman in Brunswick and following the view of the one in Hanover, that I am only a computer of notes without any ideas… Yesterday there was another article in the Constitutional Gazette of Dresden, a delightfully naïve piece, where I was reproached with having slandered Mephistopheles by making him deceive Faust… It seems Mephistopheles is a devil of virtue and integrity who does not break his word… What is more, this naïve commentator protests solemnly against the Students’ song, and assures me that German students have never gone quaerentes puellas per urbem… [looking for girls through the city] O Sancta simplicitas!… I needed to read this to believe it!

What is certain is that the last two acts of Faust have made an even greater impact than the first two and that the Ride to the Abyss, the Pandaemonium, the Ballad of King Thule, the Will o’ the Wisps, the Invocation to nature, Faust’s aria in Marguerite’s room, have, I swear it, won me all the musical hearts of Dresden.

Reissiger is very good, incomparably warm, he gives me all the help he can, he attends all the choral and orchestral rehearsals, in short his conduct is admirable.

M. von Lüttichau has already spoken to me several times to make me understand that he would very much like to keep me in Dresden and give me the direction of this incomparable orchestra… When I said to him in reply that the position was not vacant, he said to me: « Well, it could fall vacant. » Yesterday he offered a great dinner of the musicians in my honour, where the Minister of the Interior was present together with all the conductors of the orchestra and chorus (with the exception of Krebs…).

I am sending you a libretto of Faust with the preface which I had the weakness of writing in answer to the unbelievable stupidities which some papers have spread on this subject.

Several people in Dresden think that I am so obviously right that there was no need to answer.

There you are! Can I not do the same as every other composer and take from a famous poem some musical situations, arrange them in my way, without provoking the fury of German men of letters?

This is pure imbecility. Did it ever occur to the English to charge me with mutilating Shakespeare by composing the libretto of Romeo and Juliet?… Is Shakespeare less respectable than Goethe?…

I think that in the mind of some German critics there is a hostile ferment against me, which will increase in proportion to my rising musical popularity in German. Well good look to them, I shall watch with interest their rising fury.

But to attack me as a librettist, this is too idiotic.

Farewell, dear friend, I am counting on a magnificent performance on Saturday. Let me tell you for your ears that I have never seen an orchestra comparable to that in Dresden, all made of young men and virtuosos. What a change!… over the last eleven years. […]

[…] P.S. – There is an actor here, a M. Davison, who has spoken to me about you. He dined with me yesterday at M. von Lüttichau’s and is in a state of remarkable excitement. He was present at the second performance of Faust. Lipinski is absolutely delirious; the musicians shake my hands and embrace me. […]

The day after this letter, at one of the rehearsals on 28 February, one of the musicians made a sketch of Berlioz conducting.

On 30 April, the day after the third concert, he wrote to his sister Adèle (CG no. 1752 [fuller text in vol. VIII]; cf. also the same day no. 1751bis to J.-C. Lobe):

[…] Yesterday I had one of the most beautiful evenings I have experienced in my career as an artist. I had given in the great theatre two splendid performances of Faust with extraordinary success. Yesterday it was the complete Romeo and Juliet with the Flight to Egypt and the two overtures to Benvenuto Cellini. There was a crowd of people, the theatre was full and magnificent with evening dresses and uniforms; there were scenes of enthusiasm. From the boxes and the stalls crowns were thrown at me, I was called back I do not know how often, the musicians were kissing my hands and the tails of my coat… they wanted to crown me on the stage and I had great difficulty in preventing them. The performance by both singers and orchestra was a real wonder. The reconciliation scene between the Capulets and the Montagues and the religious sermon of Friar Lawrence had wonderful grandeur. And to complete the joy of this concert I had an excellent tenor [Conradi], who gave a ravishing performance of the Repose of the Holy Family, and 14 choir-boys (for the chorus of angels) with lovely voices. I was instantly asked to repeat this programme and we are repeating it tomorrow [1 May]. After this I am returning to Paris, as my leave from the Conservatoire Library has expired and the Dresden singers are about to go on vacation. […] This is now the third time in a row that I was made to delay the start of my concerts to wait for the King, and the third time that he was prevented from coming. He is not like the King of Hanover who finds the time to come even to my rehearsals. […]

[…] As a conductor I am more and more compromised with my German colleagues. One of them [Krebs, apparently] was reproaching the leader of the orchestra he was conducting: « It is a defeat for us », he said, « to have such a performance under the direction of a foreigner… ». […]

On 10 May, now back in Paris after a stop in Weimar on the way, Berlioz wrote again to Adèle (CG no. 1756):

[…] The Dresden musicians came as a body to escort me to the railway station, and those from Weimar who knew that I was arriving came to await me and then to escort me back at one in the morning.

There are rascals in Germany as everywhere else, but it must be granted that there is far greater cordiality there and a deeper feeling for art than in the rest of Europe.

I have been overwhelmed with every mark of sympathy, respect even, and affection which moves me to the bottom of my heart.

What is more I earn money there and it is only thanks to my beloved Germany that I make a living. This contrast with the indifference of Paris is beginning to cause a stir here in Paris, and this can only have good results. […]

On 4 June he wrote to Auguste Morel (CG no. 1768):

[…] In Germany I am honoured and I will not fail to go there as often as possible. Dresden’s chorus and orchestra are today the finest I know in Europe. And what fire, what love for art, what speed of comprehension! […]

Berlioz’s concerts in Dresden in April and May 1854 marked perhaps the peak of his conducting career.

![]()

On 18 October 1854 Berlioz concluded chapter 59 of his Memoirs with a reference to his recent successes in Germany, including his visit to Dresden:

[…] M. von Lüttichau, the manager of the King of Saxony, has offered to me the position of Kapellmeister in Dresden, which will soon fall vacant. « If you wish (these are his words), what wonderful things we would do here! with our musicians which you find so excellent, and who love you so much, you who conduct like so few people do, you would turn Dresden into the musical centre of Germany! » I do not know whether I will decide to settle in Saxony in this way when the time comes… This needs careful consideration. Liszt is of the opinion that I should accept. My friends in Paris are of the opposite view. I have not made up my mind, and besides the position is still occupied. There is talk of staging in Dresden my opera Benvenuto Cellini, which the admirable Liszt has already resurrected in Weimar.

I will certainly go there to conduct the first performances. […]

It seems however that the plan to give Berlioz a permanent conducting post in Dresden fell through and never became a formal offer – unlike the proposal in Vienna in 1846 which Berlioz had turned down. On 14 November he wrote to Liszt, mentioning he had just received a letter from Lüttichau ‘but he does not say a word about the suggestion he made to me during my previous trip about the post of Kapellmeister’ (CG no. 1811). It may be that there was too much local resistance to the idea, and Lüttichau simply quietly dropped it. The opportunity never came back.

The plan to stage Benvenuto Cellini in Dresden was extensively discussed in 1854 and is referred to in a series of letters in the early months of that year, mostly to Liszt (CG nos. 1691, 1739, 1746, 1748, 1756bis [in vol. VIII], 1762, 1771). The omens seemed good at first: on 2 July Berlioz wrote to Liszt that the papers in Dresden were announcing that the work was scheduled for production (CG no. 1773, cf. 1776). Then there was an unexpected setback; on 1 September Berlioz wrote to Hans von Bülow (CG no. 1785):

[…] My score of Benvenuto Cellini could not find a more intelligent or better disposed critic than you; allow me to thank you for thinking of writing the section in M. Pohl’s book [a projected book on Berlioz] which deals with it. But ill-fate definitely dogs this work; the King of Saxony gets killed just when it is about to receive attention in Dresden… This stroke of fate is worthy of classical antiquity […]

The King of Saxony had just died as a result of an accident. The following month (14 November) Lüttichau wrote to Berlioz that the theatre had decided to stage first Meyerbeer’s L’Étoile du Nord and that Benvenuto Cellini was consequently postponed till at least the end of the following year (CG no. 1811). In the meantime Liszt decided to stage once more Benvenuto Cellini in a gala performance in Weimar on 16 February 1856, in the presence of Berlioz (with another performance on 16 March). In connection with that performance Berlioz wrote two days before to Tichatschek, the celebrated tenor at the Dresden theatre who had sung for him in 1843 (CG no. 2101 [in vol. VIII]):

[…] Allow me, as one artist to another, to put to you the following request. My opera Benvenuto Cellini is being performed here on Saturday [16 February], and everything leads me to look forward to a good performance. My greatest ambition would be to see this work performed in Dresden. You would make a wonderful Cellini. Come to hear it. Perhaps you will feel satisfied with the role. Besides, if I am not mistaken, Baron von Lüttichau is very well disposed towards this work, and one word from you would be enough to clinch the matter. I would be greatly in your debt and grateful in equal measure. Liszt is encouraging me to put to you this somewhat indiscreet request, but I am sure you will forgive me in any case. In writing to you I know whom I am addressing. […]

Tichatschek replied the following day (CG no. 2101bis [in vol. VIII]):

[…] As I am very enthusiastic about those compositions of yours that I have already heard, there is no question in my mind, given that these works shine brightly on the musical horizon. It would be the greatest honour for me to take part, to the best of my ability, in your Benvenuto Cellini, if his Excellence gives instructions in August or September to begin the study of your opera for which he has particular interest, and provided no obstacles are raised against him on the part of the musical director.

A few lines from your hand to his Excellence the general manager von Lüttichau would certainly add the desired weight to hastening the staging of your work. Be assured of my most devoted zeal. […]

For whatever reason – perhaps again local resistance – the plan simply fell through; this is the last known mention of it in Berlioz’s correspondence and thereafter Berlioz had no further occasion to return to Dresden. It might be mentioned that Adolphe Jullien [Hector Berlioz (1888), p. 223] stated, without citing any evidence, that it was Reissiger the conductor who was responsible for preventing the staging of Benvenuto Cellini in Dresden.

After the visit to Dresden in 1854 Berlioz and Hans von Bülow continued to maintain friendly contacts. On the occasion of Berlioz’s visit to Weimar in February 1856, Bülow wrote to him warmly from Berlin, where he had just taken up an appointment (CG no. 2098, 10 February):

[…] The mere mention of your arrival in Germany makes me infinitely happy and revives in me the memory of the beautiful days I spent two years ago during your stay in Dresden. I am all the more disappointed not to be able to go to those fortunate little duchies of Saxony as there seems little likelihood of your coming soon to Berlin to triumph here as the admirers of your genius would like.

They may still be a small band, but they already add up to the shadow of a party, whose enthusiasm will I hope make up initially for their small numbers. […] (Bülow goes on to mention his ambition to collect in Berlin Berlioz’s scores) […]

I had hoped that you would be willing to entrust to me the arrangement of your Corsair overture for piano for 4 hands. Should you need someone to make such arrangements, may I offer my services for this purpose, and please do not consider it an excess of vanity on my part my conviction that I could do better, for example, than the rather unintelligible arrangement which has just been published of the love scene of Roméo et Juliette.

In the meantime, please accept the renewed expression of my enthusiastic admiration and of the profound devotion which I will never cease to proclaim loudly for you and your noble cause. […]

Berlioz replied at length two days later in no less friendly terms, accepted his offer, promised to send to von Bülow those scores he had available, and suggested putting on a concert in Berlin with the Te Deum and l’Enfance du Christ (CG no. 2100). In August of the same year (1856) von Bülow came to Baden-Baden to attend Berlioz’s concert there (cf. CG nos. 2163, 2168). In 1857, writing to the publisher Rieter-Biedermann, Berlioz praised von Bülow’s piano arrangement of the overture Le Corsaire (CG no. 2218). In 1858 von Bülow wrote again with news from Berlin, which prompted a very warm response from Berlioz (CG no. 2273, 20 January):

[…] Your faith, your fire, even your animosities, delight me. Like you, I still have terrible animosities and volcanic enthusiasms; but for my part I firmly believe that nothing is true, nothing is false, nothing is beautiful, nothing is ugly… Do not believe a word of this, I am slandering myself… No, no, I adore more than ever what I find beautiful, and to my mind death has no more cruel disadvantage than this: not to love any more, not to admire. It is true that you no longer notice that you are not loving any more. In other words, no philosophy, no silly talk.

But a letter of Berlioz to his son Louis a few days later, on 24 January, introduces a different and less happy note (CG no. 2274):

[…] I received a few days ago a long letter from M. von Bülow, one of the sons-in-law of Liszt, the one who married mademoiselle Cosima. He tells me that he conducted a concert in Berlin and that he performed with great success my overture to Cellini and a small vocal piece: le Jeune Pâtre breton. This young man is one of the most fervent disciples of this crazy school which in Germany is called the school of the future. They insist and absolutely demand that I be their leader and standard-bearer. I say nothing, I write nothing, I can only let them act; people of good sense will be able to see what is true in this. […]

Bülow, like his mentor Liszt, was a devotee of both Wagner and Berlioz, and was upset that Berlioz would not share their admiration, though outwardly relations remained courteous and mutually appreciative. In spring 1859 Bülow was in Paris to visit his mother in law (Countess d’Agoult) and give recitals; in the Journal des Débats of 19 May 1859, Berlioz wrote a warm review of a concert by him on 5 May (CG no. 2380, to Princess Sayn-Wittengenstein, 20 June; cf. nos. 2354bis, 2365bis, 2372ter [all in vol. VIII]. In early 1864 Bülow helped to introduce the young Danish musician Asger Hamerik to Berlioz. Despite his disappointment at Berlioz’s attitude towards Wagner, Bülow continued to admire and perform Berlioz’s music (cf. CG no. 3241, 12 May 1867), though for Berlioz the divisive issue of Wagner and his supporters had evidently affected his view of the German musical scene. For Berlioz that scene was now changing for the worse in comparison with what he had experienced in the 1840s and 1850s. A letter of Berlioz to Auguste Morel in the summer of 1864 strikes a jarring and rather melancholy note (CG no. 2888, 21 August):

[…] The day after tomorrow there is a great festival in Karlsruhe, to which Liszt has come from Rome. They are going to perform music which could tear off your ears: it is the gathering of young Germany over which Hans von Bülow presides. […]

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, all the modern photos reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in April 2008; other pictures have been scanned from postcards and engravings in our collection. © Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb. All rights of reproduction reserved.

The original city that Berlioz visited and admired in 1843 and 1854, one of the jewels of 19th C Germany, no longer is: it was destroyed in World War II by British and US air forces using phosphorus bombs in a series of raids between 13 and 15 February 1945, with the death of some 35,000 people. Though Dresden was lovingly reconstructed after the war by its inhabitants and many ancient buildings were restored, the reconstruction could only be partial.

This above picture is in the public domain.

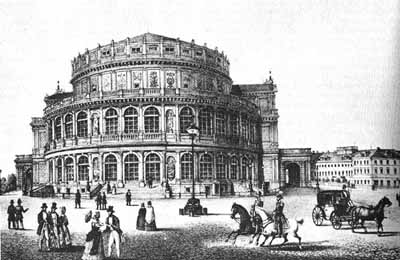

The theatre in which Berlioz conducted his concerts in 1843 and 1854 was built in the Early Renaissance style by the German architect Gottfried Semper (1803–1879), and opened in 1841. It has been known under different names: the Dresdner Hoftheater or Hoftheater for short (Dresden Court Opera House), the Theater zu Dresden (Dresden Theatre), the Court Theatre, the Semperoper (Semper Opera House), the Sächsische Staatsoper Dresden (Saxon State Opera Dresden), and the Royal Saxon Opera House. The first building was destroyed by fire in 1869.

The new theatre, the Neues Hoftheater, was also known as the Semperoper, as it was built in High Renaissance style by Manfred Semper, son of the original architect, after his father’s plans; it was opened in 1878. The theatre is situated in Theaterplatz [Theatre Square] in central Dresden on the bank of the Elbe River. During its construction performances were held at the Gewerbehaussaal (Trade Hall), Dresden’s first proper concert hall which opened in 1870. Destroyed by British and US bombing in February 1945 the opera was rebuilt almost the same as the previous building and reopened on 13 February 1985 with a performance of Weber’s Der Freischütz, the last work to be performed there before the opera’s destruction.

This engraving by J. C. A. Richter is in the public domain.

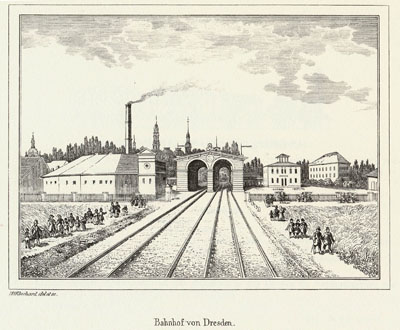

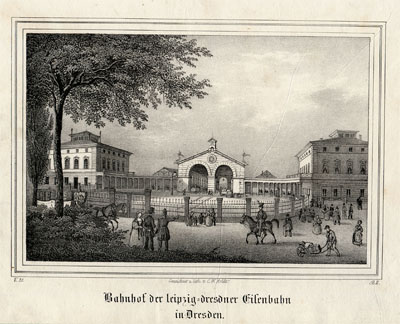

The first long-distance railway in Germany was opened between Dresden and Leipzig on 7 April 1839 – this was the line used by Berlioz on 2 February 1843 to make a return journey between the two cities on the same day, which made him exclaim to his father ‘Such is the power of railways!’ (CG no. 820). The station, called ‘Bahnhof der leipzig-dresdener Eisenbahn’, lay to the west of central Neustadt (new town), outside the old fortifications. Unfortunately nothing has survived of the original buildings. For illustrations see the page A Train Journey from Leipzig to Dresden in 1843, with reproductions of contemporary engravings.

A new railway station, the Böhmischer Bahnhof, was opened in the old city (Altstadt) in 1851, and was subsequently linked across the Elbe by a new bridge, the Marienbrücke, to the Leipzig-Dresden station and the Schlesische Bahnhof, which was also in Neustadt. The link was completed in 1852. Berlioz will have used the Böhmischer Bahnhof during his trip in 1854.

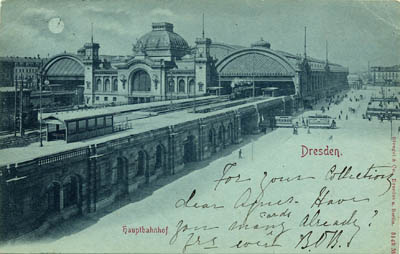

As a result of the increase in traffic between Neustadt and Altstadt, two large stations for passengers were constructed in the last decade of the 19th century – the Hauptbahnhof (Dresden’s main railway station) on the site of the Böhmischer Bahnhof to the south of the old city, and the Bahnhof Dresden-Neustadt, which took over the functions of both the Leipzig and the Schlesische stations. The Hauptbahnhof was opened in 1897, and the Bahnhof Dresden-Neustadt, built directly on the site of the old Schlesische Bahnhof, was opened on 1 March 1901. The Hauptbahnhof was damaged during World War II and subsequently reconstructed. The damage to the Dresden-Neustadt station was very limited.

This 1840 engraving shows the station as viewed from a train coming from Leipzig. The next engraving, dated 1841, shows the station building viewed from the street.

This engraving has been scanned from the Eisenbahn Journal, Special Issue, “Über 150 Jahre Dresdener Bahnhöfe”, June 1991.

This plaque marks the 150th anniversary of the establishment of Germany’s first long-distance railway, which operated from Leipzig to Dresden.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18

July 1997.

The Berlioz in Dresden page was created on 1 March 2007; enlarged on 15 February 2010. Revised on 1 March 2024.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb. All rights reserved