By Michael Wright

© 2003 Michael Wright

Berlioz celebrated his first birth centenary in 1903. At that time, though featuring in all the musical reference books, he was not generally accepted as being one of the truly great composers of the world. Much of the trouble lay in the fact that the full repertoire of his music was not played regularly, and therefore his public following was smaller than that for many other better established composers. Faced with no universally acknowledged standard by which to judge him, even his staunchest supporters somehow felt obliged to make a special case for his kind of music. Critics therefore had to make their own minds up, and usually fell back on simplistic journalistic cliché rather than considered judgement on merit.

Even the passage of another fifty years did little to change things, and it was only in the second half of the 1900s, when the right questions started being asked, that his music was at last given a chance to make itself known, and he began to be written about not from ignorance or prejudice, but with imaginative understanding.

Now in his bicentenary year, he seems finally to have thrown off his freakish image, and has come to be accepted for his positive achievements. With a misleading reputation for wild eccentricity thankfully laid to rest, Berlioz stands revealed as a serious composer and truly great original. No one ever before Berlioz wrote remotely like him, and despite his immeasurably important influence in ushering in what is now generally regarded as the romantic movement in music, hardly anyone since has been able to imitate him in his personal musical style. (An interesting comparison might be made with another nineteenth century figure, Bruckner, in many ways almost the opposite of Berlioz, a slow developer, intensely religious, godfearing and humble, one whose massive faith sustained him at the end of his life, but sharing essentially with Berlioz absolute commitment to his art, like him unique in his style and utterly devoted to his music.)

At the moment that the young Berlioz entered the world a new cultural movement was growing up around him. It was promoting fresh ways of thinking and feeling. Giving the rein to the idea of individual freedom, it advocated a

return to nature and liberation of the emotions in terms of natural behaviour. As with all  new vogues, this spirit of what came to be called romanticism came about by general consensus in all the arts. It was even in the air before Beethoven and Goethe, let alone Berlioz and Hugo. The Western world had begun to feel at the end of the 18th century that modes of expression inspired by classical notions of reason and form alone were not working to produce the

ultimate order and perfection that everyone aspired to. Rousseau’s theory of goodness inherent in human beings became attractive, and Kant’s search for enlightenment became modified by Schelling’s theory of transcendental idealism, which was taken up among others by Coleridge in the cause of literature when he asserted the supremacy of imagination.

new vogues, this spirit of what came to be called romanticism came about by general consensus in all the arts. It was even in the air before Beethoven and Goethe, let alone Berlioz and Hugo. The Western world had begun to feel at the end of the 18th century that modes of expression inspired by classical notions of reason and form alone were not working to produce the

ultimate order and perfection that everyone aspired to. Rousseau’s theory of goodness inherent in human beings became attractive, and Kant’s search for enlightenment became modified by Schelling’s theory of transcendental idealism, which was taken up among others by Coleridge in the cause of literature when he asserted the supremacy of imagination.

Berlioz felt to the full and appreciated these powerful changes in the way of thought. He grew up surrounded by the grand scenery of the Dauphiné.  When he travelled to Italy he found himself loving its country, if not its music. Faust’s invocation to nature in La Damnation de Faust, while directly inspired by Goethe, also gives the nod to earlier manifestations of the romantic element

such as the storm scene in Shakespeare’s Lear as well as to Wordsworth’s

pantheism; while the importance of the imagination is strong in almost every single work he composed.

When he travelled to Italy he found himself loving its country, if not its music. Faust’s invocation to nature in La Damnation de Faust, while directly inspired by Goethe, also gives the nod to earlier manifestations of the romantic element

such as the storm scene in Shakespeare’s Lear as well as to Wordsworth’s

pantheism; while the importance of the imagination is strong in almost every single work he composed.

Berlioz’ enthusiasms were thus not all contemporary, and were inspired by lesser names as well as great. He read (in his younger days) Florian, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Chateaubriand, then Hugo, Lamartine, de Musset, de Nerval, de Vigny, as well as Shakespeare and Goethe. He loved besides Gluck and Beethoven, Spontini and Weber.

As a sceptic, his devotional impulses became channelled into a humanistic passion for both life and art. In his Mémoires Berlioz cited music and love, “the two wings of the soul”, as the mainspring of his existence. In this, he was at one with his compatriot Stendhal, who envisaged the idea of love and music both stemming from the noblest of passions. Music was his mission on earth. Love was to be considered the embodiment of Goethe’s principle of the “eternal feminine”.

Such was Berlioz’s open personality that he was compelled to live his life according to his art. He was both dreamer and realist. In his student days in Paris  he led a Bohemian existence, wearing himself out physically and emotionally, at times acting out his passionate beliefs. Happy as he was in his childhood, he soon found himself rebelling against the provincial bourgeois values of his family. He found himself unable to accept literally the Catholic faith in which he had been brought up, although taking full advantage of its more dramatic manifestations to express musically his ideas on life and death. The classical education given him by his father had instilled in him a lifelong love of Virgil and the Aeneid, although the story as eventually told in his opera The Trojans became transformed in his version into a romantic conflict between love and duty.

he led a Bohemian existence, wearing himself out physically and emotionally, at times acting out his passionate beliefs. Happy as he was in his childhood, he soon found himself rebelling against the provincial bourgeois values of his family. He found himself unable to accept literally the Catholic faith in which he had been brought up, although taking full advantage of its more dramatic manifestations to express musically his ideas on life and death. The classical education given him by his father had instilled in him a lifelong love of Virgil and the Aeneid, although the story as eventually told in his opera The Trojans became transformed in his version into a romantic conflict between love and duty.

Love, as one of the twin wings of his soul, took up much of his life, particularly in his earlier years. A state of unrequited love chimed in with the fashionable propensity for romantic melancholy, and he found plenty of scope for that in his life. Music meanwhile served as an outlet for his passion, whether enthusiastic in mode, or endued with the sadness of isolation and yearning that made up le mal de siècle. But it was not an act; all was deeply felt. In truth, Berlioz’s excess of passion for Harriet Smithson was no mere adolescent frenzy, any more than it can be brushed aside as the behaviour of a shy introvert. Believing with the courage of his convictions in the romantic dream, he also had the nerve and the practicality to act it out. His passion for Harriet came from an artistic impulse, was indeed an extension of his artistic credo. The affair with Camille Moke offered a more normal sexual encounter – even if it did not work out successfully. His later attachment to Marie Recio was for both of them a convenient practical relationship for their maturer years – and when Marie died, he reverted to his search for the unattainable dream figure of his earliest days, Estelle Dubœuf, now a widow with the name of Fornier. It was as if he was trying to convince himself he had been right in the first place.

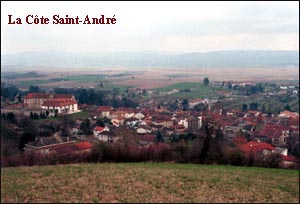

The son of a well educated professional local man, Berlioz left his roots behind him along with his landscape. Aware of his destiny as an artist of international stature, the practical side of his nature determined that he should live where he could be most effective. Once he had left for Paris in 1821, in his 18th year, Berlioz was never to return to La Côte-Saint-André, his native village, for any extended length of time. His world became Paris, at first the city of opportunity, later of disillusion. His was the professional world of music, centring around the musical academies, the concert halls, the corridors of government, the offices of journal editors, society salons, later the imperial court.

Premieres of his greatest works were given in churches and cathedrals of the capital city (St Roch for his early Messe solennelle, Les Invalides for the Requiem, and St Eustache for the Te Deum), and in its concert halls – the Paris Conservatoire serving for the Symphonie fantastique, Lélio, Harold en Italie and Roméo et Juliette, and the Salle Herz for L’Enfance du Christ. The Symphonie funèbre et triomphale received an open-air debut by a band on the move along the streets of the capital. His first opera, Benvenuto Cellini, was given – unsuccessfully – at the Paris Opéra, and that part of Les Troyens he was able to get performed, Les Troyens à Carthage was mounted at the Théâtre Lyrique; Béatrice et Bénédict had to be premiered abroad (in order to be given successfully) in Germany, at the new Theatre in Baden.

Te Deum), and in its concert halls – the Paris Conservatoire serving for the Symphonie fantastique, Lélio, Harold en Italie and Roméo et Juliette, and the Salle Herz for L’Enfance du Christ. The Symphonie funèbre et triomphale received an open-air debut by a band on the move along the streets of the capital. His first opera, Benvenuto Cellini, was given – unsuccessfully – at the Paris Opéra, and that part of Les Troyens he was able to get performed, Les Troyens à Carthage was mounted at the Théâtre Lyrique; Béatrice et Bénédict had to be premiered abroad (in order to be given successfully) in Germany, at the new Theatre in Baden.

For most of his life, then, Berlioz was compelled by circumstance to promote his music by his own efforts, conducting it himself, both at home and abroad. Later performances, or productions of others of his works, were given tirelessly in various venues, sometimes vast in area, such as the Cirque Olympique, or Palais de l’Industrie, or in the Gymnase Musical, Salle Vivienne, Salle Ste. Cécile, Salle Martinet, or at the Cirque Napoléon. Travels abroad widened the scope of his fame in more exotic locations, in imperial palaces and halls. In London, his works were given in Drury Lane, Hanover Sq., Exeter Hall and (Benvenuto Cellini, again unsuccessfully) at Covent Garden. He found himself greatly moved when he went to St. Paul’s Cathedral and heard 6,500 children’s voices singing in the tremendous space. When he travelled to Russia, he was given the use of concert halls in St. Petersburg and Moscow. One of his concerts in the latter city was heard in the enormous Riding School, where (according to his letters to friends) 500 performers played to an audience numbering an estimated 10,600.

Berlioz’s enormous reserves of energy sustained him through the greater part of his life, in his attempt to realise his ideals. Living life so intensely, however, could mean only one thing, at the end inevitable failure. On resigning from his long-standing job as critic on the Journal des Débats, Berlioz wrote: “I am … past hopes, past illusions, past high thoughts and lofty conceptions.” His spirit could only express itself in anger and

contempt for the folly and baseness of the world.

Towards the end of his life Berlioz suffered from appalling bad health. Enthusiasm and passion are virtually impossible to sustain with failing powers. Although forcing himself to the limit, he eventually had to admit defeat. Berlioz found a world which at the beginning of his life seemed at least openly receptive to his idealism, becoming increasingly oblivious to his genius. Worse, Court circles under Napoleon III were unsympathetic to the arts, and the composer was forced to fritter away any energy he had left into the vigour with which he displayed his world-weary contempt for what he would have considered “easy listening”.

And yet at heart he still believed in his original aims. It might be thought that as a man of the world he would have outgrown his vision. But just as, in his love life, after several happy years with Harriet when, her own star waning, she succumbed to drink and despair, making the liaison impossible, he was never unmindful of his own basic responsibilities for care and compassion, so, remaining true to his nature, he clung loyally to his original artistic vision to the end of his days, and never abandoned his faith either in himself or in his music.

What can we learn from Berlioz? The question must unfortunately be asked when so many contemporary producers persist in begging it by staging performances of operas written in different ages with machine guns and disco dancing instead of the originally prescribed rapiers and ruffles. One can only suppose that they imagine they are doing a favour to readers new to music by giving composers in general, and Berlioz in particular, a so-called relevance in the modern world – as if commonly speaking, most people did not have enough common sense to make the necessary comparisons without hassle in the first place. More often than not such pretentious productions merely put off potential newcomers, and do no more than distract all of us from fully understanding the precise way in which former ages may have tackled what were for them and do indeed remain for us universal and eternal truths.

Troy existed, the Trojan War may have happened, but the Homeric detail is mythical. Berlioz read the Roman epic version of it and retold the story from his own French Romantic viewpoint, producing a valid statement in a magnificent work of art. When performed it should be given the chance to deliver its message on its own terms. The field is open to anyone who has a modern message for an old myth to rewrite the story for today, and provide the music to go with it.

For most of his output, though, Berlioz’s music can make its message felt in its own terms, in the concert hall, or on disc. Today when we run round in circles debating whether science’s latest discovered gimmick is good or doubtful, and issues become more and more complicated, what, we may ask, has music to do with all this? It is true we should not lie back, let the sound tickle our eardrums, treat it as pleasant background noise and be complacent. But neither should we, feeling unfulfilled, turn cynical, and feel ungratefully that the past has little meaning, and can conveniently be ignored. Quite often the past can provide some pretty effective answers. If a new enthusiasm is needed, who better than Berlioz to deliver it? He at least can point the way by example, with his eternal values of moral courage, honesty, and passionate belief in himself and his music, while remaining overridingly if vulnerably human.

Michael Wright

![]()

See also La Côte Saint-André, Paris and London pages on this site for further information on and pictures of private and public buildings associated with Berlioz.