![]()

Introduction

The first visit (1847)

Buildings and venues

The second visit (1868)

Buildings and venues

This page is also available in French

![]()

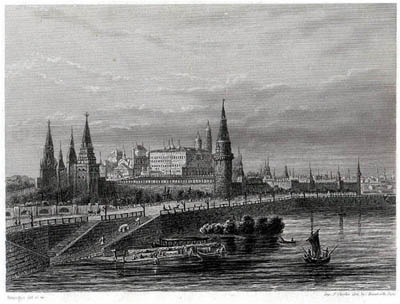

In Berlioz’s time Moscow was second in importance to St Petersburg, the imperial capital and the country’s centre of artistic activity. Berlioz visited Moscow twice, in April 1847 and January 1868, and in both cases his trips were an excursion from his longer stays in St Petersburg to which he had been invited in the first instance. There is also less evidence from Berlioz’s own writings (his Memoirs and what has survived of his correspondence) about his time in Moscow on both occasions than there is for his stays in St Petersburg, as the citations below will illustrate (all translations are by Michel Austin).

Note: the dates below are given in two forms – the first date is according to the Gregorian calendar, in use over the whole of western Europe (France, Germany, Italy etc.), and the second according to the Julian calendar which was still in use in Russia and which was 12 days behind.

![]()

Chronology

31 March (19 March): Berlioz departs for Moscow by sledge; the journey takes

four days

ca 5 April (24 March): Berlioz arrives in Moscow

ca 10 April (29 March): Concert of Berlioz in Moscow;

the Moskovskiye Vedomosti calls Berlioz the Victor Hugo of music

April (late March-early April): Berlioz attends a performance in Moscow of Glinka’s first opera, A

Life for the Tsar

20 April (8 April): Berlioz returns to St Petersburg

Berlioz was enthusiastically received in St Petersburg; the visit to Moscow was not so straightforward. He only gave one concert there, in the Hall of the Nobility, around 10 April. Obtaining a hall to give his concert was unexpectedly difficult, as Berlioz describes in chapter 55 of his Memoirs:

The Hall of the Nobility was the only suitable one for my concert. To get permission to use the hall I asked to be introduced to the Grand Marshal of the Palace, a venerable old man eighty years old, and I explained to him the purpose of my visit.

« — What instrument do you play? was his first question.

— I do not play any instrument.

— Well then how do you manage to give a concert?

— I perform my works and conduct the orchestra.

— Ha! ha! how very odd! I have never heard of such concerts. I am quite willing to allow you to use our great hall; but as you probably know, every artist we allow to use it must in return perform and be heard after the concert at one of the private gatherings of the nobility.

— Does this mean that the assembly has an orchestra that will be placed at my disposal to perform my music?

— Not at all.

— Then how can I get it played? Presumably I am not being asked to spend 3,000 francs to pay the musicians needed to perform one of my symphonies in the private concert of the assembly? That would make for a very expensive rental fee.

— Then, Sir, I regret I have to refuse your request; I have no other choice. »

After prolonged negotiations with the marshal and his wife and the sympathetic intervention of a senior officer, who advised him to put his request the following day in writing, the obstacle was overcome and Berlioz was able to give his concert in the hall:

I followed this advice, and thanks to the helpful colonel, they waived the rules but only for this occasion; my concert could take place, and I was not forced to play either the flute or the drum at the gathering of the nobility. They had a lucky escape, because rather than crossing the Volga without giving my concert, I was determined to play absolutely anything, even a mediaeval flute [Berlioz uses the word galoubet, a flute with three holes and held with one hand; the instrument is still in use]. All the same, the peculiar regulations of the Muscovite nobility’s club, which unfortunately I had not heard about in St Petersburg, caused me to lose a substantial amount of money.

There is only one surviving letter of Berlioz that gives some detail about his visit to Moscow (CG no. 1103, 20/8 April; cf. also CG no. 1102); it is addressed to the Paris publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel, one of a number of friends who had advanced money to Berlioz to make possible his trip to Russia, as he recalled later in the Memoirs (chapter 54; cf. CG no. 1101).

I have not been able to find time to do the work I promised you and for which you advanced me 1,000 francs. I am therefore obliged to refund this sum to you with my warmest thanks for your great kindness. […]

Business here has been very successful, and when I say here I include St Petersburg and Moscow.

I am leaving later today for St Petersburg where they are waiting for me to perform Romeo and Juliet at the Imperial Theatre. These good Muscovites have been turned upside down the day before yesterday by the first two parts of Faust which I managed to put on with the greatest difficulty. Here they do not have a fraction of the resources available in St Petersburg.

They have been clamouring for a 2nd concert, I have just received a letter asking for more, but I suffered too much in putting on the first, and in spite of all their displays of enthusiasm and the few thousand roubles I could still earn in Moscow, I prefer to go back to some decent music-making in St Petersburg.

Only the orchestra went reasonably well, but the chorus! Shame!!

Farewell, my dear Hetzel, I am giving your all these details because I know you are kind enough to take interest in my musical projects. […]

One evening in April Berlioz saw a performance of Glinka’s first opera at the Bolshoi Theatre (Memoirs, chapter 55):

I heard in Moscow a performance of Glinka’s first opera, A Life for the Tsar.

The huge theatre was empty (but is it ever full?... I doubt it). The scene showed almost all the time snow-clad forests of pine, steppes covered with snow, men white with snow. I still shiver to think about it. There are some very graceful and original melodies in this work, but I almost had to guess them, so imperfect was the performance. In fact, it seems that they have a very strange way of rehearsing in this theatre, despite the enthusiasm and musical ability of the director, M. Verstovsky. I discovered this when we came round to rehearsing the choruses in the first two acts of Faust which were included in the programme. [Berlioz goes on to describe how the chorus were used to rehearsing without any accompaniment…]

Berlioz stayed in Moscow for less than three weeks and then returned to Saint-Petersburg. It was to be another 20 years before he saw Moscow again.

![]()

Unless otherwise stated all pictures throughout this page have been scanned from engravings, photos, postcards and other publications in our own collection. All rights of reproduction reserved.

We are grateful to Elena Dolenko, Natalia Oleneva and V. Poljakov for information on the history of the buildings connected with Berlioz’s visits to Moscow, the programme of the first concert of Berlioz in Moscow, and the 2003 photos on this page for which they hold the copyright.

Berlioz saw little of Moscow, not even the Kremlin, which he saw only from the outside, partly because he was busy preparing for his concert, and partly because of the weather (Memoirs, chapter 55):

Moscow, a half-Asiatic city, has much to offer in the way of interesting architectural curiosities; but I studied it little during the three weeks I spent there. I was completely immersed in the preparations for my concert. Because of the thaw which was in full swing and the mild weather, the city was in any case difficult to visit. The streets were nothing but puddles of water and slush, out of which even the sledges had trouble extricating themselves. Even the Kremlin I only saw from the outside. All I did was to count the beads on the necklaces of the guns which surround it... sad relics picked up on the tracks of our dying army... There are guns of every kind, every calibre, and every country. Inscriptions in French (what a cruel irony!) even identify the regiments or the allies of France who owned the pieces from this grim collection. One of these artillery pieces received a strange wound: it has on the lip the trace of a Russian cannon ball, which struck it on the rim, entered the barrel and ploughed up the inside. Supposing the piece was loaded at the time of the accident, I leave you to imagine the shock of the cartridge inside on receiving such a hefty blow – the proud cannon must have imagined that the emperor Napoleon had resumed his former role as gunner and was loading the gun in person.

The cannons, which at the time of Berlioz’s visit were around the Kremlin, were relocated to the “Poklannaya Mountain” memorial in Moscow, dedicated to the victory in the Great Patriotic War.

Note the letter N [for Napoleon] on the cannons on the second picture.

2. The Hall of Nobility (also known as the Club of Nobility)

3. The Imperial Theatre (also known as the Great Theatre [Bolshoi Theatre])

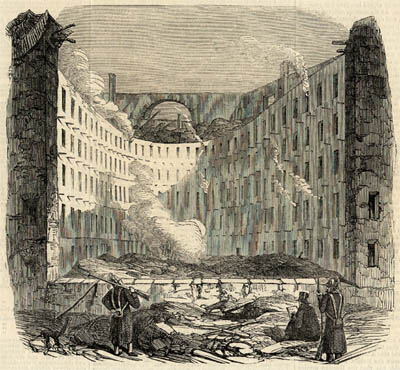

The first Bolshoi Theatre was Prince P.V. Urussov’s Public Opera and Ballet Theatre, commissioned by Catherine the Great in 1776. It was inaugurated in 1780. It was destroyed in 1805 by the first of many fires which blighted the theatre throughout its history. The building that Berlioz knew in his first visit to Moscow was built in 1824 by Bauvais and Mikhailovand, and opened its doors to the public on 6th January 1825. This was burnt in 1853 when the interior was almost entirely destroyed, but the outer walls remained more or less intact. It was reconstructed in 1856 by the architect Albert Kavos, the designer of St Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre, where Berlioz saw A Life for the Tsar for the second time in February1868.

![]()

Chronology:

1 January (20 December 1867): Berlioz

leaves St Petersburg for Moscow

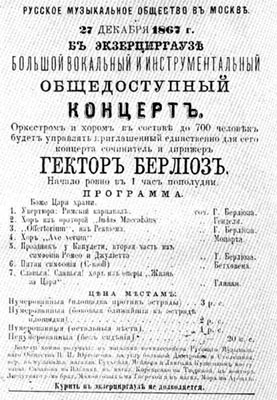

8 January (27 December 1867): First concert in Moscow

11 January (30 December 1867): Second concert in Moscow

12 January (31 December 1867): Reception in honour of Berlioz

13 January (1 January 1868): Berlioz

leaves Moscow for St Petersburg

Berlioz’s second visit to Moscow was even shorter than his first visit twenty years earlier, only two weeks in all, but it was musically more productive and rewarding: he was able to give two concerts, and the standard of playing had significantly improved since 1847. The evidence for his time there comes primarily from his correspondence – the second trip to Russia was not covered in the Memoirs which terminate in 1865. At first Berlioz, tired and unwell, was unwilling to go and initially rejected advances (CG nos. 3310 [8 December/28 November] and 3314 [14/2 December]), but within two days of the last letter his correspondence shows him discussing terms and practical arrangements with Nicolai Rubinstein, the director of the Moscow Conservatoire and brother of Anton Rubinstein, the founder of its counterpart in St Petersburg (CG nos. 3316, 3321, 3323). On 22/10 December Berlioz, still in St Petersburg, wrote to his friend the pianist Mme Massart (CG no. 3318):

[…] They came from Moscow to fetch me, which is where I will be going after the 5th concert [the 4th in practice], as the Grand-Duchess has given me permission. These gentlemen from that semi-Asiatic capital have irresistible arguments, whatever Wieniawski may say – he takes the view that I should not have accepted their offer as it stood. But I do not know how to haggle and would be ashamed to do so. […]

The first concert took place at the Manège on 8 January and Berlioz took up the baton at 1.00 pm to conduct his overture Le Carnaval romain, a chorus from Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus, the Offertoire from the Grande Messe des morts, Mozart’s Ave verum, the Fête chez Capulet from Roméo et Juliette, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and the “Slavsya! Slavsya!” chorus from Glinka’s opera A Life for the Tsar (see on this site the recollection of this concert by a contemporary). The second took place in the Hall of the Nobility on 11 January/30 December; the programme is described in a letter to Berthold Damcke the day before, and it gives a detailed account of the first concert (CG no. 3326):

I have felt so tired these last few days that I have not had the courage to write to you; and yet I have had a great musical experience. The directors of the Conservatoire in Moscow came to fetch me in St Petersburg and secured from the Grand Duchess a leave of absence of 12 days for me. I accepted the invitation to conduct two concerts. As they could not find a hall large enough for the first concert they had the idea of giving it in the Manège Hall, a hall as large as the central hall in our Palais de l’Industrie at the Champs-Elysées. I thought the idea crazy, but it was incredibly successful. There were 500 performers, and according to the police estimate an audience of 12,600. I will not try to describe to you their applause for the Fête from Roméo et Juliette and for the Offertorium from the Requiem. But I was desperately worried at the start of this piece, which had been played in St Petersburg. Hearing this chorus of 300 voices constantly repeating the two same notes, I instantly imagined the crowd would quickly get bored, and feared they would not let me finish. But the crowd understood my idea. Their attention increased and they were gripped by this expression of resigned humility. At the last bar a huge acclamation burst out on every side; I was recalled four times, the orchestra and chorus then joined in, and I did not know where to hide. Never in my life have I made such a great impression. A message was immediately sent to the Grand Duchess to inform her of this outbreak of popular emotion.

The Conservatoire is giving a second concert tomorrow evening Saturday [11 January] with its own orchestra of only 70 musicians. They have again included the Offertorium in the programme. Laub is playing the solo viola part in my Harold symphony and we are starting with the overture to King Lear. Laub is then playing the Beethoven violin concerto. We had a final rehearsal this morning and it is going wonderfully.

The day after tomorrow there is a reception in my honour in the Hall of the Nobility, where every artist in Moscow is invited. After that I shall be leaving for St Petersburg where I still have two concerts to give. I am completely exhausted, but also happy at this beautiful outcome. [...]

I thank Heller for having kindly sent his copy of my Memoirs. Despite our precautions the book took twelve days to reach my hands. I was only able to hand it over to the Princess [sc. the Grand-Duchess] on the day of my departure for Moscow. […]

A letter to his niece Nanci Suat the same day gives a similar account and adds further details (CG no. 3327):

[…] What a difference between present-day Moscow and the musical resources it had twenty years ago!

The day after tomorrow they are giving a reception for me in the hall of the Club of the Nobility, where the whole city will be present. After that I will quickly go back to give the two remaining concerts I have to conduct in St Petersburg and I will return to Paris. I can no more, I am almost all the time in bed. Getting up at eight o’clock every morning for rehearsals, and constantly seeing snow!… It is too much for my frail constitution.

Dear little niece, tell my uncle about all this; to whom else could I say it? You are my echoes when I feel like shouting for joy. […]

They want me to give yet more concerts in St Petersburg, but I am refusing everything, I am overwhelmed with fatigue. I find it perfectly honest to earn some 20,000 francs, and I do not want to commit to any further projects as I used to. A few 1,000 franc notes more or less make no difference to me. Farewell, dear little niece, I long to go and see you and then to go to sleep by the sea in the sun at Nice. […]

This is the last surviving letter from Moscow; the day after the reception Berlioz returned to St Petersburg.

![]()

Berlioz gave the first of his two Moscow concerts in 1868 in this building, on 8 January. The second, on 11 January, was in the Hall of the Nobility.

Inaugurated on 12 November 1817 the Manège was built in honour of the 5th

anniversary of the victory of the Russian troops over Napoleon to a design by

the engineer Augustin Bétancourt. Originally, this spacious building was meant for

holding military reviews, parades and exercises, hence its big size which

Berlioz compares with the Palais de l’Industrie in Paris in his letter to

Damcke above. However, as time went by, it was put to non-military uses, such as

exhibitions and concerts. In our time the Manège building is still used for

holding various exhibitions – for arts, crafts, industry, and many other

purposes. Tragically, the building was destroyed in a fire on 14 March 2004.

Within 13 months the Manège was rebuilt, and reopened on Monday 5 June 2006.

2. Moscow Conservatoire (now Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatoire)

On 12 January 1868, the day after his second concert, Berlioz was invited to attend a dinner party at the Moscow Conservatoire. Prince Odoievsky delivered a reception speech; among those who welcomed the French master were Laroche and the young Tchaikovsky.

In 1717 the piece of land which now belongs to the Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatoire was bought by the general of the Russian army Prince Vladimir Prosorovsky. In 1755 it became the property of Nikolay Dolgoruky and in 1766 passed over to Princess Ekaterina Dashkova. It was not before 1780 that the first stone building was constructed here. Fifteen years later it was reconstructed as a two-storey building with an attic and two wings (probably by Vasilij Bazhenov). In 1810, after Princess Dashkova’s death, the building was inherited by her nephew Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, a hero of the 1812 Patriotic War. During the invasion of Napoleon’s troops the building was destroyed by fire. Vorontsov had it reconstructed by Camporesi. Thereafter the Russian Music Society rented the building and in 1878 bought it for the Conservatoire from Prince Sergey Vorontsov. In 1894 the old building was taken apart in order to construct a new one, commissioned from the architects Zagorsky and Niesselsohn and the sculptor Alad’in.

![]()

Related pages on this site:

Concert in the

Manège: recollection by a contemporary

Berlioz in St Petersburg

Octave Fouque: Berlioz en

Russie (in French)

Berlioz and

Russia: Friends and Acquaintances

The

Russia that Berlioz visited,by Dr Linda

Edmondson

Hector

Berlioz as reflected in the Russian press of his time, by Dr Elena Dolenko

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the texts, photos, engravings and information on Berlioz in Russia pages.

© 2003 Elena Dolenko and Natalia Oleneva et V. Poljakov for 2003 photos.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.