This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz conducted two large concerts in Hanover Square Rooms, in 1848 and in 1853, and also took part in a matinée concert in 1852. In addition he attended concerts given there by others, for example one in 1851 where he first heard the singer Mme Charton-Demeur, and another one in 1855 conducted by Wagner. Hanover Square Rooms was the venue used for concerts by the [Royal] Philharmonic Society, after 1852 often referred to as the Old Philharmonic Society to distinguish it from the new one founded in that year which gave concerts in Exeter Hall.

![]()

The first large concert took place on 29 June 1848, at 2 pm. It was only the second one he had given in London (the first was on 7 February of the same year, at Drury Lane Theatre). Berlioz was supposed to give no less than four concerts of his own music in his first season in London, but the bankruptcy of Jullien who had engaged him nullified all these plans. Berlioz was forced to improvise: there were plans for a concert at Exeter Hall (Correspondance générale nos. 1179, 24 February; 1181 [in vol. VIII], 1st March; hereafter CG for short), and for one at Covent Garden composed of music of Berlioz inspired by Shakespeare (CG nos. 1179, 1185; 24 February and 15 March respectively), but these came to nothing. The Royal Philharmonic Society, under its conductor Michael Costa, was not receptive to his music (CG no. 1185). Eventually a concert was put together at Hanover Square Rooms; it is first briefly mentioned in a letter of Berlioz to his friend Auguste Morel dated 16 May: ‘A concert is being organised at minimal cost for June 29th; if I make £50 out of it that will be a great piece of luck’ (CG no. 1197; cf. 1199). A letter of 26 May to another friend, Louis-Joseph Duc, gives a little more detail (CG no. 1200):

[…] To finish off this chatter I will tell you that I am putting on a concert at Hanover Square Room, and that the musicians, learning of the bankruptcy of that wretch Jullien and of all the losses he has caused me, want to take part without being paid. I will therefore probably have a magnificent orchestra, composed of the élite of musicians of Queen’s theatre and Covent Garden. I will also have expenses amounting to £60 (1500 francs). It will be on 29 June. […]

A number of letters refer to the preparations for the concert (CG nos. 1202-6). The programme consisted largely of works of Berlioz which had mostly been performed at the concert on 7 February, and was as follows: (Part I) the overture Roman Carnival, the song Le Chasseur danois, the first three movements of the Harold in Italy symphony (Henry Hill, solo viola), the bolero Zaïde, the last two movements from a piano concerto by Mendelssohn played by Louise Dulcken, sister of Ferdinand David the leader of the Leipzig orchestra, a Spanish vocal duet, and the Chorus and Ballet of the Sylphs from the Damnation de Faust (Part II) the Hungarian March, the song La Captive (sung by Pauline Viardot), an aria by Bellini, a violin solo by Molique, and Berlioz’s own orchestration of Weber’s Invitation to the Dance. The concert took place at a time of considerable anxiety for Berlioz: civil war had broken out in Paris, and in a letter to a correspondent on the very day of the concert Berlioz asks urgently for news from Paris (CG no. 1208). There are references to the concert from two letters in Berlioz’s correspondence, one rather brief from a letter to Liszt after his return to Paris in which he gives a general view of his time in London: he had not been in touch with Liszt during the whole of his stay (CG no. 1216, 23 July). The other letter, dating from 11 July while he was still in London, is addressed to his sister Nancy. The text in CG no. 1210 is fragmentary; for the complete text see NL p. 321-2:

[…] As I feared, my concert did not earn me anything, what is more I lost a great deal of money.

The business of Monte-Christo at Dury-Lane had already predisposed the public to pay attention only to British events; the Queen herself had resolved to give support only to Native Talents; this is now printed on billboards; but I was counting on the French in London, and the civil war in Paris made everybody tighten suddenly their purse-strings. I could no longer step back, it was too late. The musical result was very fine, four pieces were encored, and as the public was clamouring for more I was obliged to refuse in order to allow the musicians time to go to their theatres. But my heart was so little in this damned concert, that all of this left me quite indifferent. I felt ashamed of making music at such a time.[…]

The concert, to which Berlioz had invited a number of French musicians of his acquaintance present in London (CG no. 1207), was nevertheless well received, as can be seen from two reviews published in The Times of 30 June and the Illustrated London News of 8 July. Before leaving London Berlioz thanked the musicians of Covent Garden for their help (CG no. 1210bis [in vol. VIII]).

![]()

Less detail is available for Berlioz’s participation in the matinée concert of 29 April 1852 (none of his extant letters refer to it, though they provide much detail about his concerts at the same time with the New Philharmonic Society at Exeter Hall). He conducted the overtures to Beethoven’s Prometheus and Auber’s Zanetta, Mendelssohn’s Wedding March and his own song Absence, sung by the tenor Alexander Reichardt.

![]()

The second large concert, in which Berlioz conducted the old Philharmonic Society’s orchestra, took place on 30 May 1853. Two days later he wrote to his Paris publisher Brandus about it (CG no. 1601, 1 June):

The day before yesterday I appeared again before the English public in the 4th [in fact the 6th, according to P. Citron] concert of the Philharmonic Society of Hanover Square. It was risky. All the cohorts of the Classical School had turned up in force.

The performance of Harold had astonishing verve and precision, and I could say the same about the Carnaval romain.

I received huge applause despite the fury of four or five intimate enemies who, I was told, were writhing in their corner. My new piece in an antique style (Le repos de la Sainte famille), delightfully sung by Gardoni, made an extraordinary impression, and had to be repeated. I had never heard it, even on the piano; I can assure you it is very nice.

Davison came to embrace me after the concert full of joy, though he has not yet written anything. There is a superb article in yesterday’s Morning Herald, though I do not know who is its author. Write a few lines for Sunday’s Gazette Musicale if you can. Mention Sainton, the leader of the Covent Garden orchestra, who gave an outstanding performance of the solo viola in Harold.

Bottesini also scored a great success; he performed with his usual incredible facility a new double-bass concerto of his, a remarkable work which is pleasant and well orchestrated. All my friends here tell me that this success at the Old Philharmonic Society was immensely difficult to achieve. There was a dense crowd and I was pleased to notice that a large part of the audience had come just for me, since a third of the hall departed after the performance of my last piece. […]

The second half of the concert, which did not include any of Berlioz’s works, was conducted by Michael Costa. On 21 June George Hogarth, the Secretary of the Society, thanked Berlioz on behalf of the Philharmonic Society and offered him a princely £10 as a reward for the concert. Nevertheless the concert was important in establishing Berlioz’s credentials with the Philharmonic Society, and may have encouraged the society to approach him late in 1854 with an offer to conduct all eight concerts of the 1855 season after the unexpected resignation of its conductor Michael Costa – but by then Berlioz had already committed himself to a much less favourable contract with the rival New Philharmonic Society.

![]()

The origins of the Hanover Square Rooms date back to 1773, when Giovanni Gallini bought a mansion at No. 4 Hanover Square and built on the site of the garden a new suite of rooms, named New Assembly Rooms, later to become the Hanover Square Rooms or the Queen’s Concert Rooms. Gallini was a Swiss-Italian dancing master who came to Britain some time in the 1750s, obtained work with the ballet at the King’s Theatre in Haymarket, and later became its manager.

In 1861 the Hanover Square Rooms underwent extensive alterations and redecoration and reopened in February 1862. But in spite of these improvements the musical life of Hanover Square Rooms had not long to run and in 1875 they were converted into a club. The last concert was given by the Royal Academy of Music on 19 December 1874.

Many musicians performed at the Hanover Square Rooms besides Berlioz, among them Haydn, Paganini, Mendelssohn, Marie Malibran, Charles Hallé, Joseph Joachim, Jenny Lind, Clara Schumann, Charles de Bériot, Thalberg and Madame Pleyel.

(For further details on Hanover Square Rooms and their history see our source: Elkin, 1955.)

The modern photos reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in 2002; other pictures have been scanned from engravings, prints, newspapers and books (Carse, 1948; Elkin, 1955) in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

No. 4 Hanover Square, on the site of whose garden the Hanover Square Rooms were built, was on the east side of the square, at the north-west corner of Hanover Street. The above picture is a reproduction of a painting by Edward Dayes (1763-1804), the original of which is in the British Museum.

The principal room was on the first floor on the right of the above picture.

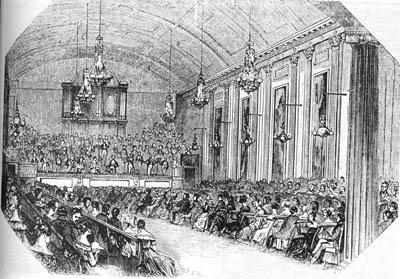

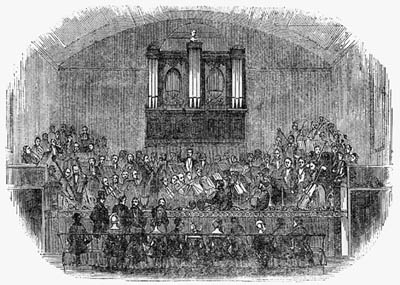

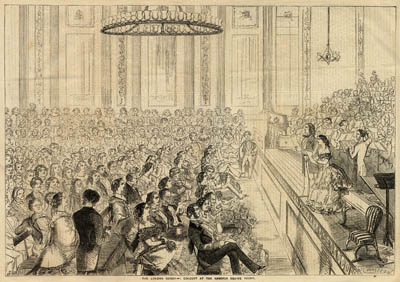

The Hanover Square Rooms were not adequate for the performance of music requiring large forces – the principal room had seating room for an audience of only six hundred.

The above engraving was published in the Illustrated London News in 1843.

This engraving was published in the Illustrated Times on 12 July 1856.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.