Berlioz’s engagement at the Drury Lane Theatre

Illustrations:

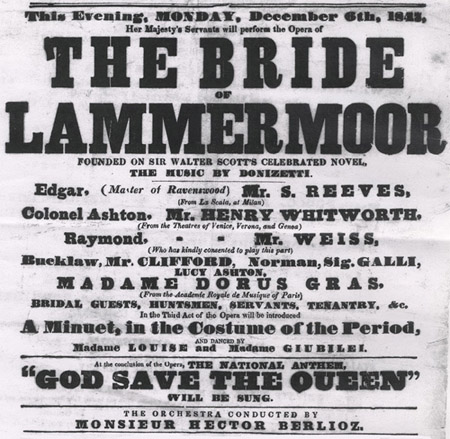

The Bride of Lammermoor

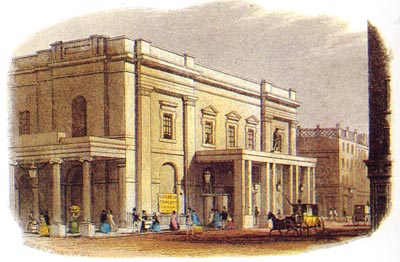

The Theatre Royal Drury Lane

This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz’s first visit to London, between November 1847 and July 1848, was the longest of his five visits. He came on an invitation by the French-born director of the Drury Lane Theatre, Louis-Antoine Jullien (known simply as Jullien). Berlioz was engaged to conduct concerts and the orchestra of the Grand English Opera which Jullien had in mind to establish at the Royal Theatre, to provide London with its first national opera in English. The terms of the engagement seemed very attractive and offered the prospect of a secure future in London. The appointment also gave Berlioz his first chance to conduct opera in an opera house. There was also a poignant personal connection: it was at Drury Lane that many years before Harriet Smithson had made her début in London (see elsewhere on the site a poster announcing her appearance as Zamora in Honey Moon at Drury Lane Theatre in 1827).

At first everything looked very promising, and Berlioz’s letters to his friends and relatives at the time reflect his excitement. Soon after his arrival, he wrote to his father, in what turned out to be the last known letter he wrote to him (Correspondance Générale no. 1134, hereafter abbreviated to CG):

I am writing these few lines to you in something of a hurry, to tell you of my arrival in London and give you my address. […] We will be spending the rest of this month and a few days of next month in preparations and rehearsals, as the Grand English Opera can only open around 10 December. I have already seen my orchestra at work and it is one of the best I could have wished. I found in it a good number of French and German musicians I know, and they welcomed me with great displays of joy. I have every reason to believe that everything will go perfectly in my department. I will now busy myself with writing a piece on the theme of God Save the Queen for the opening day of the theatre. I had not thought of it, but Jullien, who has an eye and an ear for everything, would like me to repeat here the scene of the Hungarians in Pesth by working in the same way on English national feelings. Besides it is customary for this famous anthem to be performed in all great ceremonies of this kind. [Note: this particular project never materialised]

My concerts will only start around mid-January; the English translator of my scores will have time to perfect his work, I will know my performers better and we will have settled down. This delay consequently suits me, and prudence suggested it. I am very surprised at how much English I know; I can say almost everything I need to and without too much of an accent, but I have difficulty in understanding half of what is said to me. There is serious work to be done here. […]

A few days later, on 10 November, he writes to the cellist Tajan-Rogé whom he had recently seen in St Petersburg (CG no. 1135):

[…] You do not have a clear idea of my life in this dreadful city [Paris], which claims to be the artistic centre of the world. I have at last escaped from it. Here I am in England with an independent position, from the financial point of view, such that I had not dared to aspire to. My task is to conduct the orchestra of the Grand English Opera house which will open in Drury Lane in a month; I am also hired to give four concerts composed exclusively of my works, and finally to write a three act opera intended for the 1848 season. The English Opera will only be running for three months this year and will only have a very incomplete company for six because of the rush in which it has just been organised and a fatal circumstance which will deprive us this year of the participation of Pischek (a wonderful German musician on whom we were relying). The director is prepared to make every sacrifice and is only counting on the second year. Jullien, the director, is a man of boldness and intelligence who knows London and the English better than anyone else. He has already made his fortune and has got it into his head to make mine. I am letting him go ahead, since to achieve this goal he proposes to rely exclusively on methods that satisfy art and good taste. But I have my doubts… […]

I have come to London on my own, and you can guess the reasons why. Besides I had a prodigious need for the kind of liberty of which until now I have always and everywhere been deprived. To seize it back required not one but a series of coups d’état. And yet so long as we have not started our large-scale rehearsals the isolation in which I am living seems strange to me. […]

The rest of the month was taken up with preparations and rehearsals. The Drury Lane season eventually opened with Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor on 6 December under Berlioz’s baton (see the poster reproduced below); Marie Recio had travelled from Paris accompanied by James Davison to attend the occasion. It was a great success, as Berlioz relates to his friend Auguste Morel two days later (CG no. 1149; cf. 1151, 1152):

[…] And now I must tell you that the opening of our Grand Opera has scored a huge success; the whole of the English press is in agreement in singing our praise. Mme [Dorus-]Gras, and the tenor Reeves (in Lucia) were called back 4 or 5 times with frenzied applause. In truth they both deserved it. Reeves is a priceless discovery for Jullien; he has a charming voice which has genuine quality and is agreeable, he is a very good musician, has very expressive looks and performs with his native Irish fire. When I entered the orchestra the audience gave me a wonderful reception. We started with a superb performance of Beethoven’s fine overture Leonora no. 1 [probably what we know as no. 2]. In Lucia the great sextet in D flat which begins the finale of Act II was encored, and at the second performance this evening, the audience also asked for the chorus in E flat in Act III to be repeated. […]

The English are astounded to hear in an English theatre this vast body of 120 choristers and this fine orchestra, and to have an outstanding tenor and such a prima donna. Only the ballets are miserable, but we will soon have something better. Try to get all this favourably noticed in the Monde Musical, the Gazette des Théâtres and the Gazette Musicale, and elsewhere if you are able to. […]

Berlioz’s letters for November and December convey an air of optimism about the Drury Lane venture, though reading between the lines it is possible to detect signs of worry on his part which he generally kept to himself, and his previous experiences of Jullien should have been a warning. By early the following year the alarming truth could no longer be concealed, as he wrote to his friend Auguste Morel on 14 January (CG no. 1162; cf. 1163, 1165):

[…] I am working here like a horse in a mill, rehearsing every day from noon to 4 o’clock and conducting operas in the evening from 7 till 10. It is only since the day before yesterday that we have not had rehearsals and I am beginning to recover from a bout of flu which was worrying me, the result of fatigue and the cold draughts in the theatre. You have probably heard of the dreadful position in which Jullien has placed himself and dragged all of us with him. And yet to minimise as far as possible the damage to Jullien’s credit in Paris do not pass on to anyone what I am going to tell you. It is not the Drury Lane venture which has turned his fortunes upside down; they were already ruined before the season opened and he had probably counted on extravagant takings to revive them. Jullien remains the same madman you have known, he does not have the least idea of what running an opera house involves, nor even of the most obvious prerequisites for a good musical performance. He opened his theatre without possessing even a single score of his own, with the exception of the opera by Balfe which inevitably had to be copied out. We have only kept afloat till now through the goodwill of Lumley’s agents who are lending us the orchestral parts of the Italian operas we are staging. At this moment Jullien is doing his tour of the provinces and is earning a lot of money with his promenade concerts; here the theatre gets every evening quite respectable takings and in brief after having been made to agree to a cut of one third in our salaries we are no longer being paid at all. Only the choristers, the orchestra and the workmen are paid on a weekly basis, so that the theatre can continue to function. Yet Jullien sold two weeks ago his music shop in Regent’s Street for nearly 200,000 francs… and I cannot be paid, and the principal actors, the set designer, the coaches of the singers and the dancers, the stage manager, everybody is in the same position as myself… Can you imagine?

And yet he protests that we will not suffer any loss and we keep going, and the public is only too keen to come. But in London Jullien’s credit is completely gone… […]

There is now a good place for me to occupy here which has been left vacant through the death of poor Mendelssohn. Everyone keeps saying this to me from morning to evening, the press and the musicians are very well disposed to me, and the two rehearsals I conducted for Harold and the Roman Carnival, and for two parts of Faust, have opened wide their eyes and their ears wider still. I have reason to believe that it is here that I must create a good position for myself. As for France, I no longer think about it […]

In the next few weeks, while carrying on his work at the theatre until the end of its three-month season, Berlioz rehearsed actively for his concert on 7 February, his first in London and thus one of great importance for him (CG nos. 1164, 1166, 1167, 1170). The concert was composed exclusively of his own music and included the overture Le Carnaval romain, the song Le jeune pâtre breton, the symphony Harold en Italie, the first two parts of La Damnation de Faust, and excerpts from Benvenuto Cellini, the Requiem and the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale. In a letter to Auguste Morel on 12 February Berlioz gives a detailed account of the reception he received (CG no. 1173; cf. 1174, 1181, 1185):

It is only today that I have time to write to you; my concert took place last Monday with resounding success, and the performance had magnificent verve, power and precision. We had done five orchestral rehearsals and eighteen for the chorus. My music has caught on the English public like a trail of gunpowder, and I was called back after the concert, they encored (as elsewhere) the Hungarian March and the Scene of the Sylphs. Anybody who is anything in London musical life was at Drury Lane that evening, and the majority of musicians of any worth came to congratulate me after the concert at the theatre. There were not expecting anything of the kind; they thought my music was going to be diabolical, incomprehensible, harsh and without charm… You have to see the way they handle our Paris critics. Davison himself has done an article in the Times, half of which was omitted through lack of space; what was left did nevertheless make an impact. But I am not sure what he really thinks; with opinions like his anything can be expected. Old Hogarth from the Daily News was in a comical state of excitement: « All my blood is boiling, he told me, never in my life have I been so excited by music. » […]

Try to do something on this concert in your newspapers; have a look at the English papers of the 8th at Galignani’s and those of tomorrow Sunday 13th. They are the Morning Post, the Times, the Morning Herald, the Chronicle, the Daily News, the Sunday Times, etc. Next Thursday [17 February] the Symphonie funèbre is being performed at Prince Albert’s. The director of the Prince’s Military Band was saying to me yesterday: everybody is delighted except for our composers.

When I ascend the rostrum at Drury Lane to conduct the opera in the evening, I am always greeted with a round of applause. […]

Berlioz was particularly delighted with his success with the London critics, and wrote to many of them to thank them personally (CG nos. 1175, 1176 [see vol. VIII], 1179). One of the contemporary reviews of the concert, from the Illustrated London News of 12 February, is reproduced on this site together with a short biographical article on Berlioz from the same paper; they bear eloquent witness to the success of Berlioz with the London public. See also another review of the same concert published in The Times of 8 February.

The concert on 7 February was meant to be the first in a series of four, but the other three lapsed: by April Jullien had been declared bankrupt and was imprisoned (CG no. 1191). After various unsuccessful attempts Berlioz only managed to organise one more concert in London during his stay, on 29 June at Hanover Square Rooms.

Berlioz had placed high hopes in Jullien and had initially been inclined to take his promises at face value, perhaps against his better judgement; his disappointment at the outcome was consequently all the greater. Jullien subsequently promised to pay Berlioz what he owed to him, and may have been sincere in his intention to do so (see his letter of 1 December 1849 to Henry Chorley in NL p. 343-4). But Berlioz never demanded anything and received nothing (CG nos. 1245, 1260, 1631). Although he continued to believe in Jullien’s good intentions, later references in the Memoirs (chapter 57 and Postface) and in the Soirées de l’orchestre (9th Evening) betray his lingering bitterness: Jullien had become for Berlioz the archetypal lunatic, and is referred to as such in several letters in his correspondence even after Jullien’s death in 1860 (CG nos. 2538, 2843, 2888).

![]()

|

|

|

![]()

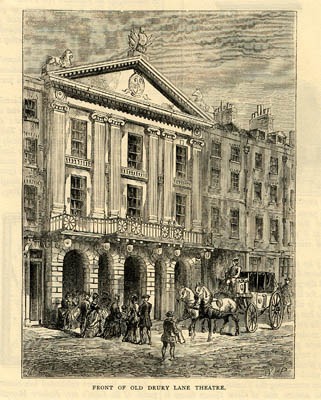

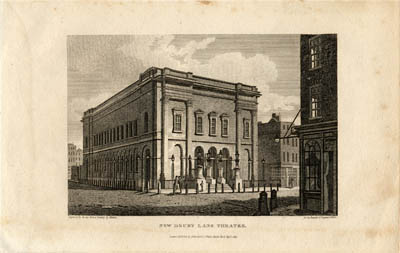

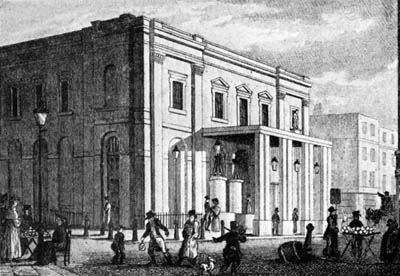

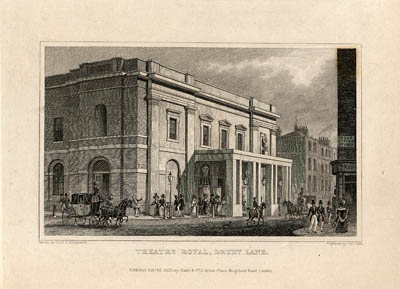

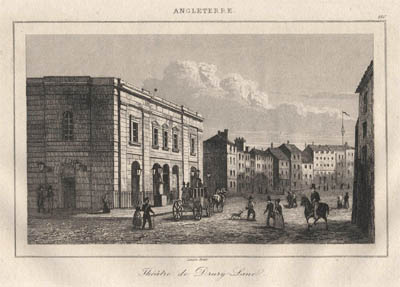

The Theatre Royal Drury Lane was first built in 1663; subsequently it was destroyed by fire or pulled down on several occasions and went through three further reincarnations. The fourth and present building, which is the one Berlioz knew, was designed by Wyatt and opened on 10 October 1812. It is situated in the West End of London; its current repertoire consists almost entirely of musicals and it no longer stages operas. The last opera heard there was probably in winter 1958 when Gorlinsky gave a two-month season of Italian operas.

All the modern photos reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in 2001; other pictures have been scanned from engravings, prints and books in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]()

The above engraving was published in Old and New London, Cassell, Petter & Galpin (London, c.1880).

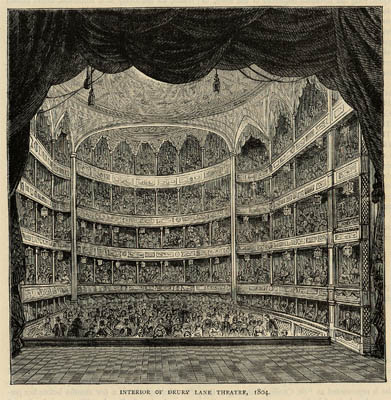

The above engraving was published in Old and New London, Cassell, Petter & Galpin (London, c.1880).

The above engraving was published in La Belle assemblée, volume vi (supplement), in 1813. The theatre had been opened in 1812.

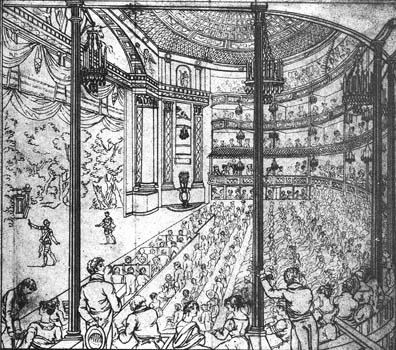

The above engraving by Busby, from a drawing by Wichelo, was published in London by John Harris in September 1813.

The above engraving, drawn by Theo. H. Shepherd, and engraved by Theo. Dale, was published in London by Jones & Co. in February 1828.

The above engraving, drawn by Theo. H. Shepherd, and engraved by T. H. Ellis, was published in 1845. It shows the Wrestling Scene in Shakespeare’s As you Like It.

The above engraving, published in the Illustrated London News in 1847, shows Jullien’s promenade concert in the redecorated Drury Lane Theatre.

A copy of the above engraving is in the library of the Paris Opera.

The above picture is a watercolour by E. B. Musman, published in The Londoner’s England by Avalon Press & William Collins, London, 1947.

The original painting in this print is by G. H. Powell (1876-1934).

![]()

This pub, situated opposite the main entrance of the Theatre Royal across the small square, was built long before the theatre; Berlioz could have had a drink or two there.

![]()

This page was created on 1 January 2002; substantially enlarged on 11 December 2015.

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.