![]()

Introduction

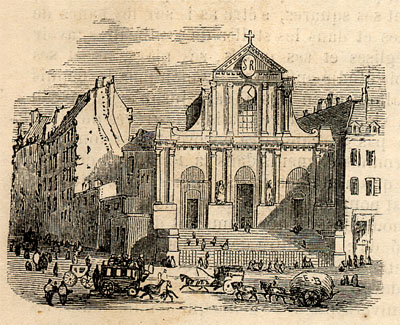

Église Saint-Roch in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

Built between 1653 and 1740 the church of Saint-Roch, one of the largest in Paris, has very special associations with Berlioz’s career: it was in this church that on 10 July 1825 was given the first performance of his first large scale work, his Messe solennelle. The performance created a stir and brought the young composer to the notice of the Paris public, before he was even formally registered as a student at the Conservatoire. The work had been composed in 1824 but a planned performance in December of that year did not come off, and Berlioz took the opportunity to revise the Mass before it eventually reached its first performance. In his Memoirs, Berlioz gives an account of the composition and performance of the work (chapters 7 & 8; an earlier version of these chapters was published by Berlioz in October and November 1858 in Le Monde Illustré). Written many years after the event the account plays down the significance of the work, but several letters of Berlioz of 1825 provide more detail and show how much the work and its first successful performance meant to him at the time, particularly in view of the opposition of his parents to his plans for a musical career. First a letter to his uncle Victor, months before the performance (CG no. 41, 18 February 1825):

[…] I have high hopes in a Missa solemnis which is certainly going to be heard within four or five months. Recently I tried to get it performed, as you may have heard; but the impossibility of assembling without paying them the large number of musicians that it requires, and the excessive difficulty of performing a work which is not destined to be repeated often, have proved insurmountable obstacles. I have just touched up my score and removed all the major difficulties; I have shown it again to M. Lesueur, who after reading it closely for four days returned it to me with the comment: « It is disheartening that your parents should be trying to stop you; I have now no doubt whatsoever that you will succeed in music, and it is clear that you will achieve great things. This work shows incredible imagination and a profusion of ideas that astounds me; the trouble is that there are too many. Restrain yourself, and try to be simpler. » And here is what he said about my mass to somebody who repeated it to me. « This young man has fantastic imagination; his mass is astonishing; there are so many ideas in his score that I could write ten of my own with them. But he cannot help it; he must absolutely fire his guns and blast the world. » The conductor of the Opéra [Valentino] said more or less the same to me, and after studying my score for a week he undertook to conduct the performance. I received a letter of compliments and advice from M. Lefebvre, the organist of Saint-Roch, who had attended the rehearsal which we started and which I cut short, the day before I was to perform my mass in this church [27 and 28 December 1824]. A gentleman of my acquaintance was talking to him directly, and among other things M. Lefebvre said: « In a few years he may well be our leading composer. » […]

Then after the first performance on 10 July two letters which repay comparison; the first is addressed to his mother (CG no. 47, 14 July):

You may have heard from Edouard Rocher that I have scored a rather brilliant success with the performance of my Mass. The reason I have so far delayed in communicating this to you is not that I had the slightest doubt that the news would please you; despite your and my father’s wish that I should turn my studies in a different direction, your tenderness for me is too great for you to be pained by an event which has caused me such great joy. Let me tell you, dear mother, that the only cause of this delay is that I was anxious to see my success acknowledged by the press. There are six papers that offer me encouragement and praise, but unfortunately not one of them is available in La Côte; they are l’Aristarque, le Drapeau blanc, le Moniteur, le Corsaire, and le Journal de Paris. I buy them as they appear, as I want to arrive equipped with these testimonials.

I had the finest performance that can be seen, with 150 performers; the support from my teacher, from the director of the Opéra, from the conductor and especially the dedication of the performers have enabled me to overcome the greatest obstacles.

As soon as the performance was over I was showered under with compliments, questions and invitations of all kinds, and I was at a loss who to answer. But I was far from being satisfied by the infatuation of these amateurs; what I was craving for was the approval of professional musicians and only of real connoisseurs, and I was fortunate to gain this. What a joy to hear all those musicians, jaded with music critics, come to tell me that I had made them shiver, that I had fire in my belly, that my crescendi had made them breathless, that I would go a long way, that I had to restrain myself, etc., etc., etc. After enduring for fifteen minutes a harangue from the minister of Saint-Roch, who wanted to demonstrate to me that J.-J. Rousseau had perverted musical taste as he had done for literature, and that I was destined to lead the public back to the right path, I took refuge with my teacher who had let me know that he was waiting for me.

When I entered M. Lesueur embraced me; by then I did not know where I was; he manifested to me his joy, his satisfaction, I would even say his delight, and this moved me very deeply. Then he told me that he had hidden away in a corner of the church so as not to be recognised, and had heard and seen the prodigious effect my music had on the public. Mme Lesueur and her daughters who were sitting in another part of Saint-Roch also related to me what they had seen and heard, the compliments they had received on my behalf, and the dismay of Berton’s pupils who were particularly annoyed at all this.

So I have now taken the first step successfully, but all the same I could see how much I need to work; numerous flaws which had escaped the mass of the public, swept away as they were by the fire of the ideas, were pointed out to me; I recognised them and will endeavour to avoid them another time. […]

The second is to his friend Albert Du Boys in Grenoble (CG no. 48, 20 July):

[…] My mass has been performed.

Perfectly (this must be true for the author to say it).

By 150 musicians — from the Opéra and the Théâtre-Italien.

Valentino was conducting.

Prévost was singing. […]

I believe my mass made a tremendous impact, particularly the powerful movements like the Kyrie, the Crucifixus, the Iterum venturus, the Domine Salvum, and the Sanctus. When I heard the crescendo at the end of the Kyrie, my breast was swelling like the orchestra, my heart-beat followed the strokes of the timpanist. I have no idea what I was saying, but at the end of the piece, Valentino said to me: « Try to keep calm, my friend, if you do not want me to lose my head. » In the Iterum venturus, after getting all the trumpets and trombones of the world proclaim the arrival of the Last Judgement, the chorus of mankind, drying up with terror, was let loose. My gods! I was swimming on this tumultuous sea and drinking in the flood of sinister vibrations. I would not leave it to anyone else to blast my audience, and after announcing to the wicked, with a final salvo of brass, that the time of tears and gnashing of teeth was at hand, I hit the tam-tam with such force that the whole church trembled. It is not my fault if the ladies in particular did not think it was the end of the world.

The crowd of amateurs declared itself in favour of the Gloria in excelsis, a brilliant piece written in a light style, and this was to be expected.

The most interesting moment came just after the performance of my work. Within two minutes I was surrounded, pressed, overwhelmed by the musicians and players, and the audience that filled the church. Someone grasped my hand, someone else tugged at my coat: « You have fire in your belly. — You must restrain yourself, Sir, you might kill yourself. — I still have goose-flesh. — Young man, you will go a long way, here are some real ideas. — This is a knock-out blow for many, and from where I stand I can see some long faces. »

Gradually the general public crossed the barriers into the orchestra and asked the musicians to point to the author. One of the most excited was running, knocking down chairs and stands on his way until he reached me: « Please tell me, Sir, where is the Kapellmeister? — Do you mean M. Lesueur? I said — No. — M. Valentino, who was conducting the orchestra? — No, no, the author of the music. — It is I, Sir. — Ah… ah… ah… ah… ah… ah… » And I left him at the first syllable of his alphabet. Compliments were raining down like hail. Here I was asked if my best piece was not the Sanctus or another movement that won favour. Elsewhere I was assured that I was no devotee of absurd music, that all my ideas did depict the situation, that all my notes hit their target. In the midst of all this, the Lesueur daughters and their mother came to tell me that my teacher was expecting me at home. I was about to dash off when a messenger from the minister forced me to go to the sacristy to listen to a fifteen-minute speech. The priest wanted to convey to me that my ideas were from the heart and not the head. « Ex pectore, Sir, ex pectore, as the great Saint-Augustin said. » I finally got away and rushed to my teacher’s home, rang the bell, and Mlle Lesueur opened the door. « Papa, here he is! — Come, let me embrace you; I swear you will never be a doctor or pharmacist, but a great composer; you have genius, and I tell you this because it is true. There are too many notes in your mass, you have allowed yourself to be carried away, but through the profusion of ideas not one of your intentions fails to come off, and all your depictions are true; the effect is incredible. I want you to know that this effect was experienced by the mass of listeners, as I had deliberately positioned myself in a corner to observe the public; I can vouch that had this performance not been taking place in a church, you would have received three or four memorable rounds of applause. »

My dear Albert, I will leave it at that; I cannot tell you everything, but will relate to you in person all the most interesting details. […]

The newspapers that talk about me are:

Le Moniteur of the 11th.

Le Journal de Paris of the 11th.

L’Aristarque of the 11th.

Le Corsaire of the 13th.

Le Drapeau blanc of the 13th.

Les Débats of the 14th.

La Quotidienne of the 15th. […]

The Messe solennelle was performed a second time, on 22 November 1827, but this time in the larger church of Saint-Eustache and with Berlioz himself conducting. On this occasion too there is a detailed account of the performance in a letter of Berlioz shortly after the event, in addition to the mention in the Memoirs (CG no. 77). Despite the success of the performance Berlioz subsequently became dissatisfied with the work and destroyed it, preserving only the Resurrexit which subsequently provided music for the Tuba Mirum of the Requiem (1837), the end of Act I of his opera Benvenuto Cellini (1838) and the Christe of the Te Deum (1849). Remarkably, a copy of the complete work was rediscovered in 1991 in a church in Antwerp, Belgium, and published in 1994. It revealed further unsuspected borrowings by Berlioz from this early work in later compositions: Lesueur was right to comment on the profusion of musical ideas that characterised the Messe solennelle.

![]()

All the modern photographs reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in 2002; the 19th century engravings are from our own collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

The above engraving was published in a book entitled Les Églises de Paris (Paris, 1843), a copy of which is in our own collection.

The above engraving was published in the 5 March 1859 issue of Le Monde Illustré, a copy of which is in our collection.

The foundation date of this shop, 1638, precedes the construction of the church, which was apparently built around it.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.