This page is also available in French

![]()

In Berlioz’s career in London, the name of Covent Garden is particularly associated with the failure of his opera Benvenuto Cellini on 25 June 1853. But before that Berlioz had been a frequent visitor to the opera house. For example in 1851 he attended there performances of Weber’s Der Freischütz, Beethoven’s Fidelio, and Mozart’s Magic Flute, all of them in Italian, which was mandatory in that opera house at the time. He reviewed these performances at length in several feuilletons in the Journal des Débats in 1851 (respectively 31 May, 1 July and 12 August), and in the second article he also commented on the long-standing rivalry between Covent Garden (under its manager Frederick Gye) and Her Majesty’s Theatre (under its manager Benjamin Lumley), a rivalry which subsequently played a part in the hostile reception given to Benvenuto Cellini in 1853. He also made critical remarks on London’s dislike of rehearsals and the habit of the conductor Costa of adjusting the orchestration of works he performed. None of these articles were reproduced by Berlioz in 1852 when he devoted the 21st evening of the Soirées de l’orchestre to the musical life of London as he had experienced it in 1851.

In 1853 Berlioz was invited back to London by Frederick Gye, the director of Covent Garden, to stage his Benvenuto Cellini at the opera house in Covent Garden (now the Royal Opera House). Benvenuto Cellini had just been successfully revived in Weimar by Liszt in 1852, and it seemed likely that the work, which had failed disastrously at the Paris Opéra in 1838, was set to enjoy a new life. The rehearsals had all gone very well and Berlioz was very pleased with his Cellini (Tamberlick), Teresa (Madame Jullienne) and Ascanio (Madame Didiée). The favourable response to the concert he gave on 30 May at Hanover Square Rooms was a good omen, and everything seemed to point to a great success. The opening night, on Saturday 25 June 1853, was thus keenly anticipated and brought together a distinguished gathering, including members of the royal family, princes from Germany, critics and music-lovers from London and abroad. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the blind King and the Queen of Hanover, and the Duke and Duchess of Gotha were among those present.

On the night, however, an organised body of opposition was determined to ruin the performance, though Berlioz claims that he had not been warned of this. In his correspondence Berlioz describes the disastrous occasion. First, in a letter dated 27 June to his staunch supporter Armand Bertin, the editor and proprietor of the influential Journal des Débats, he writes (Correspondance générale no. 1608, hereafter abbreviated to CG):

Yesterday Benvenuto fell at Covent Garden exactly as in Paris. The difference is that the opposition showed its hand in advance and so its plan was discovered. A society of Italians had organised themselves as early as last Thursday to bring the opera down; they even booed the overture to the Carnaval romain during its performance. Several pieces were nevertheless encored, among them the arias of Fieramosca and Ascanio, and the first overture, though because of its length I decided not to play it again. See the article in The Times, which is not an analysis of the work but a fairly accurate account of the evening.

Generally speaking the press is hostile to the score, and in my view the critics are off target as far as the music is concerned. I am criticised for excesses in my use of instruments which are not even there: for example the bass drum, which does not play a single note in the whole opera; the other criticisms are of the same kind. On the other hand there is a large number of very determined supporters; I was greeted on my entrance with prolonged applause and recalled for ten minutes at the end of the first act. But you can imagine that I had the good sense not to appear. […]

That same evening I withdrew the work, as I did not want to expose myself to the continuation of this Italian hostility, nor to that directed against Covent Garden by the people from Her Majesty’s Theatre who have lost their jobs because of Lumley’s bankruptcy, for which M. Gye is esponsible. […]

And in another letter on the same day to the publisher Gemmy Brandus, Berlioz writes (CG no. 1609):

A formidable Italian army, organised for the last two weeks (though nobody had dared to warn me), came to cause mayhem during the whole evening of the 1st performance of Benvenuto. The actors were booed before they had even opened their mouth and the Carnaval romain overture was booed during its performance. With the exception of the Times and the Morning Herald the English press does not stigmatise this fact clearly enough, and is off target as far as the music is concerned. See the Times in particular.

[…] I am told that the Italian cabal intends to persevere with even greater fury if I carry on.

They are clamouring that Covent Garden is being invaded by foreigners. Because Mme Jullienne is French, Mme Didiée is French, Tagliafico is French, Zelger is Belgian, Formès is German, Stigelli is German, and they are appearing in a Frenchman’s opera. They have also enlisted the support of Lumley’s people, who have been dispossessed by Gye of Her Majesty’s Theatre.

I will withdraw my work, and there is no room for hesitation. […]

The most detailed account of the performance itself comes from a letter of 10 July, just after his return to Paris, written by Berlioz to Liszt, a staunch champion of Benvenuto Cellini (CG no. 1617):

[…] In spite of this [uproar] I did not loose my self-control for one moment and did not make a single mistake in conducting, which rarely happens to me. With one exception my actors were excellent and the performance by the chorus and the orchestra was among the most brilliant one could imagine. […]

Tamberlick played and sang Benvenuto with the greatest nobility and warmth. He was particularly wonderful in his last aria: Sur les monts les plus sauvages and in the recitative where he points to the fiery statue emerging from its shattered mould and sings the Latin inscription:

SI QUIS TE LÆSERIT EGO TUUS ULTOR ERO

which is indeed to be seen on the Perseus in Florence and which I make him fling in the face of his detractors in the last scene.

Fieramosca (Tagliafico) scored a great success, and the audience encored his aria in the second act, but the shouts of the cabal prevented me from repeating it.

The Ascanio was charming (Mme Didiée) and she was allowed to repeat her aria. Despite its complexity the grand finale on Piazza Colonna was performed to perfection and with great clarity. […]

It might be worth mentioning the reaction of Queen Victoria to the performance, which is known from an entry in her personal diary. In her opinion Benvenuto Cellini was ‘one of the most unattractive and absurd operas I suppose any could ever have composed. […] There was not a particle of melody, merely disjointed and most confused sounds, producing a fearful noise. It could only be compared to the noise of dogs and cats!’ (cited in Michael Rose, Berlioz Remembered [2001], p. 183).

Berlioz did conduct once again at Covent Garden, on 6 July 1855, but it was a purely orchestral concert. The composer’s correspondence gives little evidence about this occasion (CG no. 1999). Apart from the two Berlioz pieces mentioned in this letter, the programme comprised Weber’s Euryanthe overture, Italian arias, the quintet from Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte, Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia for piano, chorus and orchestra, Ernst playing on the violin his Carnaval de Venise, and Rossini’s Stabat Mater. It was the last concert Berlioz ever conducted in London.

![]()

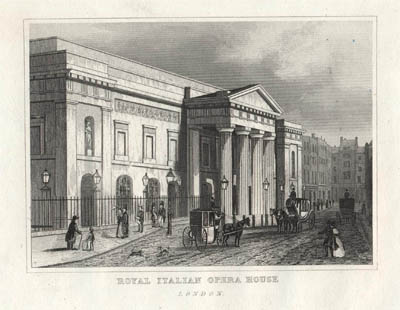

Since its establishment in the 18th century the building has changed hands between various opera companies and also been rebuilt or redecorated a number of times. At the time Berlioz was in London for the performance of Benvenuto Cellini the building was in its second reincarnation and had been occupied by the Royal Italian Opera since 1847. The company took up the lease and the architect Albano was engaged to make drastic structural alterations to turn the auditorium into the traditional Italian horseshoe-style opera house. The second Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, thus became the Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden. It opened on 6 April 1847 with Rossini’s Semiramide, conducted by Michael Costa. Its repertoire consisted largely of Italian works, and the foreign operas which were staged had to be performed in Italian. Berlioz’s Cellini was translated into Italian too. The building Berlioz knew was burnt down in 1856. The third and present building was designed by Edward Barry and opened in 1858. In 1892, as Scholes (1947, p. 260) points out, “the word ‘Italian’ was dropped out of the title, a principle being now established of performing operas not in Italian but in their original language.” In the mid-1990s the building underwent extensive refurbishment and restorations.

Unless otherwise specified, all the modern photos reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in 2001 and 2002; other pictures have been scanned from engravings and newspapers in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]()

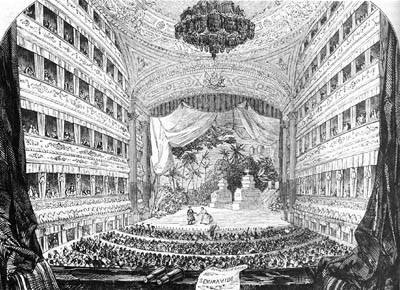

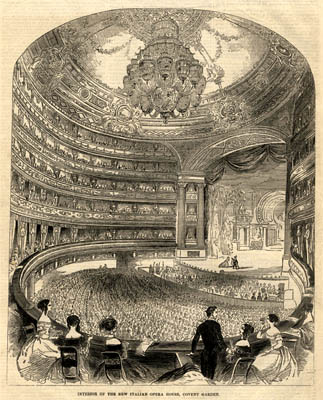

The above two pictures are courtesy of A. Saint et al., A History of the Royal Opera House (London, 1982).

This engraving, published in the Illustrated London News of 10 April 1847, shows the opening of the new Opera House with a performance of Rossini’s Semiramide.

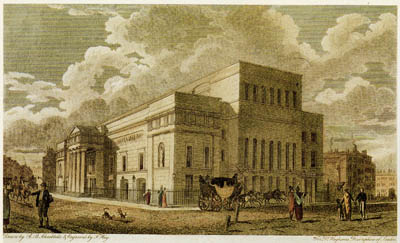

This engraving appeared in The Pictorial Times of 3 April 1847.

This engraving was published in Old and New London, volume 3, Chapter XXIX, Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1878.

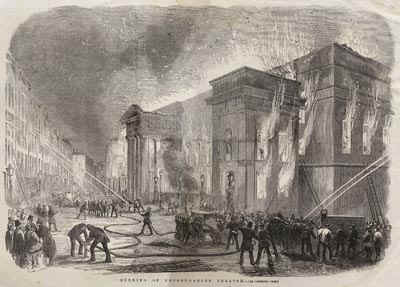

This engraving has been scanned from the 15 March 1856 issue of the Illustrated London News.

The above two pictures are courtesy of A. Saint et al., A History of the Royal Opera House (London, 1982).

![]()

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.