![]()

Introduction

The Festival

Selected letters (all of 1844)

Journals (all of 1844)

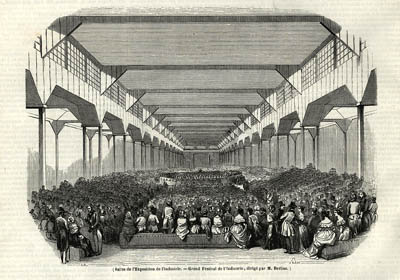

Festival de l’Industrie in pictures

This page is also available in French

![]()

The large concert which Berlioz gave in the hall of the Festival of Industry on 1 August 1844 holds a special place among the many concerts he gave in Paris during his career. It brought together over 1000 musicians (1022, according to the account published by Berlioz later), which represented a very large proportion of the musical forces available in Paris; these were further augmented by delegations from some of the provincial cities. The audience was vast — writing to his father after the event Berlioz gives a figure of 8000; it was, he says, ‘the greatest music festival that had ever been given in Europe’ (CG no. 919). The concert represented the partial fulfilment of a dream that had haunted Berlioz for a long time, that of bringing together for a special occasion all the musical resources of the capital city; this dream he had outlined in the last section of his Treatise on Instrumentatnion and Orchestration which had just been published as a book in March 1844. Whatever the results from the purely musical point of view, to have conceived, organised and brought to life such a concert represented a monumental achievement which enhanced its author’s standing in public esteem. It provided the model for subsequent large-scale concerts by Berlioz, at the Cirque Olympique in 1845 and at the Palais de l’Industrie in 1855.

The importance Berlioz attached to the concert in his conducting career may be seen from the fact that several years later he published a detailed account of it under the title ‘Memories of the musical world’ [Souvenirs du monde musical] in the journal Le Monde Illustré (13 February 1858). The evident success of this article incited the publisher to ask Berlioz to serialise those chapters from his unpublished Memoirs which related specifically to his musical career, and they appeared in the same journal from September 1858 to September 1859 under the title ‘Memoirs of a musician’ [Mémoires d’un musicien]. The account of the concert of 1844 became later chapter 53 of the posthumously published Memoirs, substantially as it had first appeared in 1858 (references below will be given to the final version in the Memoirs, and not to the original publication of 1858). The account in the Memoirs is supplemented and verified by contemporary material of 1844: these include a number of letters of Berlioz, a selection of which appears below in English translation, and articles from various journals, one of them by Berlioz himself, and a selection of these is also reproduced below in translation. All translations are © Michel Austin.

![]()

The Festival at which Berlioz conducted on August 1st consisted in fact of two concerts: that of Berlioz, and a second, much lighter one on August 4th, directed by Isaac Strauss (1806-1888). The Festival was intended to celebrate the closing of the Exhibition of the Products of Industry which had opened on May 1st and was to run to the end of June. Berlioz’s account in the Memoirs gives the clear impression that the decision to organise the two concerts was taken by himself and his associate Strauss not long before the Exhibition was due to close — in other words in June 1844 or possibly the month before. But this raises a difficulty: a letter of Berlioz co-signed by Strauss shows them approaching M. Delessert, the Préfet de police (Chief of Police) of Paris, with a developed proposal to conclude the Exhibition with a Festival consisting of two concerts and a dinner (CG no. 888). The letter is given the date ‘March 1844’ in CG, but this itself is problematic. The letter does not contain any indication of date and seems to assume that the Exhibition had already opened and was in progress; the dating to March goes back to the initial publication in Le Ménestrel (12 September 1880, pp. 324-5) of two letters of Berlioz relating to the Festival which were in the possession of Strauss, who communicated them to the journal for publication (the other letter is CG no. 912). The March date is merely stated but not explained or justified (it may have been supplied by Strauss himself, but if so it is not known on what grounds). If the date is correct, it shows that Berlioz had been thinking of a concert in that venue several months before the Exhibition had even opened; but this does not square with Berlioz’s own statement (Journal des Débats, 23 July), that it was only while he was visiting the Exhibition that the idea of a concert occurred to him. It seems therefore that the letter belongs in reality to a date later than March, and should be placed some time in May and after the opening of the Exhibition.

Whatever the date, M. Delessert refused at first the proposal on grounds of public order, as the Memoirs relate, and his opposition had to be overcome by lobbying behind the scenes. This seems to have taken many weeks, if the initial approach is correctly dated to March: writing to Ludwig Schlösser in Darmstadt on 20 April Berlioz implies that he will soon be free of concerts and in a position to go abroad: ‘I have just given three concerts here and am organising a fourth at the Théâtre Italien, after which my musical season in Paris will be over and I will be only too delighted to wander around, particularly in your direction’ (CG no. 895 [see vol. VIII]). This could of course be read to suggest that at that time Berlioz and Strauss had not even made their approach. But by the following month events had moved on. A letter of Berlioz dated 19 May carries a probable reference to preparations for the festival concert but implies that the matter was not yet decided (CG no. 902). If the interpretation is correct, it was not long before the concert became a certainty: on the 1st of June Berlioz was sending round invitations to musicians in Paris to register for the concert (CG no. 904; cf. also CG no. 909bis, 911). In the event the majority of professional musicians in Paris participated, including many amateurs, but there were conspicuous exceptions, notably most of the players of the Conservatoire and their conductor Habeneck (CG no. 912). There were also contributions from some provincial cities, notably Lille (CG nos. 909D, 912; Journal des Débats, 23 July). On 14th June Berlioz wrote to August Barbier, one of the librettists of Benvenuto Cellini and the author of the Hymn to France that he was setting to music specially for the Festival (CG no. 905, cf. 909D), while excusing himself on the same day to another poet, Adolphe Dumas, for being unable to set to music his Song of the Workers, another item in the programme (CG no. 906). Still on the 14th Berlioz was writing to his publisher Maurice Schlesinger to explain his delay in completing the writing of Euphonia (CG no. 908; the serialisation in the Revue et Gazette Musicale had started in February, and in the event the last instalment did not appear till 28 July). The organisation of the Festival was immensely demanding (CG no. 915), not least because of the system of sectional rehearsals which Berlioz insisted on (CG no. 904; Le Ménestrel, 21 July; Journal des Débats, 23 July); yet Berlioz still found time to write an extensive article on the musical instruments displayed at the exhibition (Journal des Débats, 23 June), as he was to do later for the exhibitions in London in 1851 and Paris in 1855. It should also be remembered that throughout this period his domestic circumstances were extremely fraught (CG nos. 910, 920).

When Berlioz and Strauss first approached the authorities (whatever the date), the date for the festival was placed by them in early August (CG no. 888). By the time the decision to go ahead had been reached the suggested dates had been brought forward to July (CG no. 904), but were then pushed back to near the end of the month (CG no. 909D and the poster published in mid-June). Eventually the date for the main concert was fixed for the 1st of August, and Berlioz announced the whole Festival and its programme in a detailed article which naturally glossed over all the battles he had had to fight to bring it about (Journal des Débats, 23 July).

As well as Berlioz’s own (objective) assessment of the concert in his Memoirs (chapter 53), a long letter to his father more than two weeks after the Festival gives a very detailed account (CG no. 919). As he says there, the reaction of the press varied, depending on whether the reviewers and their papers were more or less sympathetic to Berlioz. The short notice in the Journal des Débats the next day (2 August), though anonymous, may have been inspired by Berlioz himself (it gives the same total of musicians, 1022, as his letter to his father). The reviews in the Revue et Gazette Musicale (4 August) and of Le Ménestrel (4 August) were generally positive, while that in L’Illustration (10 August) was more critical. Noteworthy is a review in The Times (5 August), which differs in some details from Berlioz’s own account (for example it gives the total number of performers as 1025 against Berlioz’s 1022). It is generous in its praise even though the most notable feature of the concert was an outbreak of anti-English feeling prompted by the singing of a chorus from Halévy’s Charles VI, which caused Berlioz and Strauss problems with the authorities, as related in the Memoirs (cf. also CG no. 919). All accounts, particularly that of L’Illustration, agreed on the sonic limitations of the hall; Berlioz himself conceded the point after the event, but this did not prevent the concert as a whole from being a great public success, and all were agreed in acknowledging Berlioz’s achievement and the remarkable ensemble achieved by the vast musical forces. Yet financially the rewards fell far short of expectations, because of the enormous expenses involved, the high tax levied for charitable institutions (something Berlioz resented very strongly), and the relative failure of Strauss’ concert on the 4th — the authorities had vetoed the initial plan of holding a ball — even though tickets for the second concert had been priced much lower (Journal des Débats, 2 August). The whole episode left Berlioz exhausted; initially he had been planning to go to Baden-Baden later in the month (CG nos. 919, 920), but in the event he followed the advice of his friend Dr Amussat and went to spend a month in Nice to recover from his exertions. On his return he was soon approached with a proposal to follow up the success of the August concert with a series of large-scale concerts, to be given in the early months of 1845 in the Cirque Olympique.

We are most grateful to the Hector Berlioz Museum for granting us permission to reproduce on this page a scanned copy of the programme of the Festival, and to M. Jean-Claude Luc for sending us an image of pages 371-3 of l’Ilustration, 10 August 1844, from which the text of the article translated below have been taken.

![]()

Berlioz and Isaac Strauss to the Préfet de Police Delessert (CG no. 888, March [?]; for the date see above):

Sir,

On some occasions cities in Germany and England put on music festivals which always excite to the highest degree the interest of lovers of art, and are at the same time a source of noble enjoyment for the population. A few cities in northern France have followed this example; Paris is alone in not having had yet a genuine festival.

An opportunity has arisen to acquaint it with the impact and importance of these solemn occasions. The idea is to organise, from the 3rd to the 6th of August, after the conclusion of the Festival of the products of industry, a large-scale festival in the vast halls in which this exhibition is taking place. The plan for the festival is as follows:

On the first day, Saturday, a concert would take place from 2 to 5 o’clock, in which large-scale compositions, the theme of which would relate to lofty national ideas, would be performed under the direction of M. Berlioz, one of the signatories of this letter. A thousand musicians would take part, who would constitute the totality of the vocal and instrumental resources of Paris, Versailles, Rouen and Orléans, augmented by delegations sent by the main Philharmonic Societies from the regions. Two days later, on Monday, a large ball, held also during the day, would bring together for a second time the more affluent part of the audience of the concert. The ball would be directed by M. Strauss. The price of the tickets for the concert would be 10 francs, 5 francs and 3 francs. The tickets for the ball would cost 10 francs. Tickets would be purchased in advance from various ticket offices. A maximum of 500 people would be admitted, at a price of 10 francs, to the general rehearsal which would take place the day before the concert.

Finally the festival would conclude with a subscription dinner, over which the main manufacturers and exhibitors would preside.

The Minister of Commerce, to whom we have submitted the project, is very much in its favour and believes that such a festival would provide a worthy culmination to the dignity of the Exhibition. The means of bringing it about are within our grasp, provided we are enabled to start our preparations fairly soon. For this we need your authorisation and support, Sir, and beg of you, if this project seems to you worthy of encouragement, to specify to us what conditions are demanded by the needs of the public security services. In this connection, please allow us to meet you to provide you verbally with more detailed information. […]

To his sister Nanci (CG no. 902, 19 May):

[…] And with all this I have to finish my book on Italy [Voyage musical en Allemagne et en Italie], correct the proofs of my symphonies, and organise an immense undertaking which I will tell you about if it comes to fruition and which will cause a greater stir on its own than everything I have attempted so far. […]

To Mademoiselle Jacques (CG no. 904, 1 June):

A Festival spread over two days will be taking place in the hall of the exhibition of the products of Industry, on 18 and 21 July (Thursday and Sunday) at one o’clock in the afternoon. I have been charged with organising and conducting the Concert on the 18th, for which I am trying to bring together all the vocal and instrumental resources that exist in Paris.

The Programme consists exclusively of pieces written in a straightforward and broad style, which consequently are not very difficult. It should therefore be possible for us to perform them after two rehearsals. To begin with there will be sectional rehearsals for the orchestra and the chorus, either in the royal Salle du Garde meuble, or in any other venue in the centre of Paris; the second general rehearsal will then take place in the hall of the exhibition. There will be a voucher for 15 fr.

If you are able to take part in this grand performance, please come to register before June 20th with M. Ferrière at the Conservatoire. […][Similar letters will probably have been sent to many other musicians]

To Auguste Barbier (CG no. 905, 14 June):

I have found at last the music for your magnificent Hymn to France, and as of yesterday you are on display on posters on every wall in Paris. I believe it is going to be fairly grand and simple enough in its form to be able to bear as well as possible the crushing burden of the comparison which will not fail to be made between your verses and my music. I have done my best. As for the performance it will be fairly grandiose; for the Hymn to France there will be five or six hundred singers and four hundred instruments.

The last stanza in particular is orchestrated in a monumental style. […]

To Adolphe Dumas (CG no. 906, 14 June):

Do not be too hard on me! I made vain attempts to think of something worthy of your poetry [the Chant des Industriels], but I had to give up as my inventions (if my efforts can be dignified with that name) were utterly worthless, and the occasion is too solemn to risk a failure, particularly in the company of such fine verses as yours. […]

To Maurice Schlesinger (CG no. 908, 14 June):

I am so engrossed in the business of the Festival that it is very difficult for me to find the time to write; but I will soon finish our eternal Euphonia which is reaching its conclusion and will constitute at the most one large article or two of average length. […]

Berlioz’s uncle Félix Marmion to Nanci (CG no. 909D, 26 June):

[…] Your brother, from whom I had asked a service (I put my request nicely!) is telling me that his great festival in one of the halls of the exhibition is in hand for July 29th — there will be a mere 900 musicians. The northern cities are asking him to welcome delegations of their best artists — the fire is spreading. He adds that he is completing a piece, the Hymn to France, with verses by M. Barbier, one of the leading poets of the day. […]

To an unknown correspondent (CG no. 909bis [in vol. VIII], 20 June):

Many thanks for the trouble you have taken in sending me the names of your pupils and for asking them to take part in the performance at the festival. They will receive shortly a letter of invitation. […]

To his sister Nanci (CG no. 910, 23 June):

I thank you for your kind letter, and you should not be angry with me for my slowness in replying; you more or less know the reason. The great Festival which I am organising for the end of July is bristling with monstrous difficulties. But I hope to get it under control. My only worry concerns the receipts, which also need to be on an enormous scale if I am to earn anything from it. Well, it is a battle that has to be fought. But my domestic circumstances only get more horrible; I do not have a moment’s peace now. I have rented a flat in the countryside; she [Harriet] stayed there for a fortnight and when she came back my torment started again. […]

To Isaac Strauss (CG no. 912, 25 June):

The matter is in hand, and everything is going as hoped; but I am worried about the second concert, and there is a mass of details, even for the first one, which make your absence very problematic. I beg you, come back as soon as possible to enlist your orchestra and assist me in the rehearsals which are about to begin. This is of the highest importance. As could be expected, Habeneck is doing his little bit of obstruction; his supporters consist of seven people and we are already more than nine hundred!! It is rather funny. You know that the city of Lille is sending a delegation of its leading artists, who are coming at their own expense to take part in the performance. Try to make sure there is also someone from Lyon, it would make an excellent impression (and even from Moulins and Dijon). […]

To Robert Griepenkerl (CG no. 915, 26 July)

To his father (CG no. 919, 19 August):

You probably cannot understand the silence I have been maintaining since the great business of the Festival… I wrote no more than a few lines to my uncle, while taking a bath, after emerging from this battle. It is an immense success for me; you probably have no idea of it because of the newspapers you receive, Le Siècle and the Revue des Deux Mondes. If you would take the trouble to read the others which are not hostile, I would send them to you. I also believed that I had made a very handsome profit, since my concert on the first day had receipts of thirty seven thousands francs! We were anticipating that the ball-concert conducted by Strauss on the second day would attract the crowds, the middle classes and the general public… but that did not happen… I had the — admittedly rather unpleasant — satisfaction of seeing that popular music no longer has an audience. Strauss had receipts of only two thousand six hundred francs, and since we were associates, the expenses for the second day had to be paid from the receipts of the first. Then, since artists are (in France) real serfs who can be taxed and exploited at will, the administration of charitable institutions came to deduct five thousand francs and M. Delessert, the Chief of Police, who had sent a veritable army of municipal guards and policemen etc. to maintain order, allocated to these gentlemen the modest sum of twelve hundred and thirty-one francs. So much so that after paying all this crowd of performers, printers, copyists, engravers, carpenters, dealers in wood, zinc, canvas, furniture etc. all that is left to me from these huge receipts is a net profit of eight hundred and sixty francs…

The Ministers attended the rehearsals and the concert, wrote some fine letters and paid for their seats like ordinary citizens; one of them paid 40 fr. for four seats, another 150 for fifteen. But ministers have no more money than the city of Paris, which is unable to pay herself its policemen and imposes them on us in exorbitant numbers.

You can see whether I am wrong in saying that artists, in France, are serfs. We pay the tithe. I have been charged this year, for my five concerts, nearly nine thousand five hundred francs. Such is the freedom we enjoy. Such is the fine recompense I have received from the authorities, for having staked my life and given in Paris the greatest music festival that has ever taken place in Europe. But it is already a great deal that I was allowed to go ahead, and up to the last moment I had my doubts.

It was, I swear to you, a striking spectacle, quite apart from the musical interest!!! The enthusiasm of an audience of eight thousand… the deep silence between each piece; the shouts and hurrahs afterwards; all the men standing up, waving their hats, and clamouring for a repeat of the final stanza of my Hymn to France. There was a terrible moment (both political and musical), when the refrain of Halévy’s song: « Never in France will the English rule » was intoned. It was like an insurrection, a war cry, the first rumblings of a European revolution.

The concert over I was half-dead, as you can imagine, I was brought clothes and underwear, then they built for me on the stage, in the middle of the orchestra, a small chamber with harps with their covers on and I had a complete change of clothes before coming out. I had been profusely bled a few days before, and I could feel my chest tightening up.

I have been feeling better for a few days, but I was really exhausted and I was coughing dreadfully. Amussat assures me that is just a matter of having a complete rest… but rest can no more be bought at the market than sleep, leisure and oblivion.

All the same I expect to be off to Baden-Baden in a few days where I will try to avoid doing anything strenuous. […]

To his sister Nanci (CG no. 920, 24 August):

You probably have had news of me from my father who will have passed on to you the letter he received from me [CG no. 919]. The true reason for this long silence I cannot give to you exactly; there are a thousand, of which the principal is the permanent torment in my domestic life. Things have gone so far, even during these dreadful rehearsals for the festival which left me half-dead on returning home, that being unable to put up with sleepless nights spent with eyes open and the ear assaulted with shouts and insults, I was forced to take a room away from home where I go to sleep every evening. I show up at home as little as possible. Next Wednesday I will very probably be leaving for Germany. She [Harriet] has finally agreed to return to the countryside during my absence and I have given notice for my flat in Paris. […]

![]()

Journal des Débats, 23 June (in French)

— The first rehearsals for the monster-festival of M. Berlioz have taken place this week in Salle Herz, and promise the most splendid results. The Blessing of the Daggers from Les Huguenots, performed by five hundred players and five hundred singers, would be enough to set the whole of Paris running around. This is going to be magnificent!

Journal des Débats, 23 July (pp. 1-2)

FESTIVAL OF INDUSTRY.

I will not be saying anything new if I repeat after so many others that Paris is the capital of the civilised world. The superiority of Paris for everything that relates to the arts, and in particular for musical performance, cannot be questioned. Witness all the singers and virtuoso players of whatever country: the reputation and successes they may have achieved anywhere else mean nothing to them, so long as they have not received the solemn consecration of the plaudits of the Parisian public. As for ensemble music, all are agreed, foreigners included, that the orchestra of the Paris Conservatoire is the finest in the world. It is true that in the course of my travels in Germany I have had nothing but good experiences; everywhere, with one or two exceptions, I have found excellent orchestras, even if their numbers were occasionally restricted to the bare minimum. But nowhere have I found the unheard-of ensemble, the perfect unanimity of feeling and expression that is displayed by the orchestra of the Paris Conservatoire, which are due, I believe, to the superiority of the string players who have all been taught at the same school, have the same style and the same technical mastery. The result is that the parts for violins, violas, cellos and double-basses all give the impression of being performed by a single player who makes one gigantic instrument vibrate under his powerful bow.

But Paris can be proud not only of the talent of its orchestral players but also of the great number of players of talent it possesses: their quantity deserves as much praise as their quality. How many orchestras, and how many excellent orchestras it has! The Opéra, the Opéra-Comique, the Théâtre des Italiens, the salle Vivienne. If you step into the vaudeville theatres, at Porte-Saint-Martin, at the Cirque-Olympique, and even at the Théâtre-Français and at the Odéon, you will find dispersed there the elements of two or three good orchestras. The same numerical superiority is to be found for vocal ensembles. We have the choruses of the Opéra, the Opéra-Comique, and the Théâtre des Italiens, which comprise fine voices and good musicians, and various choral societies and a fairly large number of singers of merit who are attached to churches.

It is thus abundantly clear that Paris is the city in the world that is richest in musical resources of every kind. But how regrettable it is that by a strange anomaly Paris has not yet been able to bring them together in a vast ensemble on even a single occasion, and in its turn put on a festival, as done by the principal cities of Germany and England, and even by some of our provincial cities of the second or third rank. The idea of a festival in Paris has been conceived by many; myself I have more than once pondered how it could be brought about, but I have always been stopped at the outset by one insurmountable difficulty, the impossibility of finding a suitable venue.

I have never ceased to be preoccupied with these thoughts and regrets, and they were with me when I went, like the whole of Paris, I might even say the whole of France, to visit the Exhibition of the products of industry. I ask their forgiveness from the industrialists, but I confess that the various marvels exhibited before my eyes were not the first object of my thoughts. Hardly had I set foot in the vast building at the Champs-Élysées, that I was struck by the idea that the art of music might well in its turn come and settle in this temple erected to industry. What a fine setting for a festival, I thought!

From idea to execution there is only one step, so it is said. The thought occurred to me on this occasion, though that step was rather difficult to take. I shared my thoughts first with the main conductors and chorus masters of Paris, who enthusiastically adopted it. Then for the practical organisation I turned to the entrepeneurs and builders of the structure of the Champs-Élysés who promised their active cooperation with an alacrity for which I thank them.

Once sure of the means of execution, I turned to the authorities to obtain permission to give a large two-day festival in the building of the Exhibition of the Products of Industry. The Ministers and General-Secretaries of the Interior and of Commerce, the Préfet of the Seine department and the Préfet of Police, moved by the interest which they can always be expected to show for great artistic enterprises, were kind enough to greet my request with a goodwill for which I am happy to express my gratitude. The local authorities in particular devoted all their care to this matter and went into even the smallest details; they supervised and approved the various measures that were taken for the convenience and comfort of the audience, and to make sure that good order would reign without interruption in this vast gathering. The aim is not, as it is said, to make a little more noise. The musical impressions that result from a colossal ensemble are fundamentally different from those produced by ordinary means; they are not violent, as many people believe, but have extraordinary grandeur and majesty. They should particularly be so in a venue such as the one in question, whose sonority, now that the interior is free, is the most excellent that I have yet observed.

The various practical steps that have or will be taken are as follows. It is the vast gallery of the machines that has been assigned for the festival. The performers, numbering about one thousand, will be placed in the middle of the gallery on a platform raised one metre above level ground. The numbered seats will be those nearest the orchestra which they surround on every side; then will come the second and third category of seats. But all members of the audience will be placed in the hall of the machines in such a way that everyone can see and hear.

All the artists of Paris, choral singers and instrumental players, answered with alacrity the invitation which I addressed to them. All the singers who comprise the personnel of our lyrical theatres even offered me their services spontaneously. It seems even that my voice found an echo in distant locations where I did not hope it could be heard: Lille is sending a delegation of its musicians, and under the direction of M. Bénard, the conductor of the theatre, and of the distinguished composer M. Lavainne, will be undertaking an artistic pilgrimage to Paris to come and take part in the work of the festival. My thanks to these generous artists!

The rehearsals for the vocal parts have already started. The chorus of the Opéra, the Opéra-Comique, and the Théâtre des Italiens are rehearsing in their respective theatres, under the direction of M. Laty for the first, M. Lebel for the second, and M. Tariot for the third. M. Benoist is rehearsing the artists of the lyrical theatres, M. Banderali the students of the Conservatoire, and M. Dietsch the various amateur singers who are not members of any institution in Paris. When these various choral sections will have studied enough separately they will come together in salle Henri Herz.

Rehearsals for the instrumental parts will start this week. As with the vocal rehearsals they will be sectional. M. Tilmant the elder, the able conductor of the Théâtre des Italiens and the deputy of M. Habeneck at the Conservatoire, will rehearse the violins; [violas,] celli and double-basses will rehearse under the direction of M. Desmarest, one of the leading cellists of Paris; I will take charge of the wind instruments, and I have entrusted the direction of the percussion instruments to M. Auguste Morel, and that of the harps to M. Strauss.

1° Overture to La Vestale (Spontini) ; 2° Scene from the third act of Armide, choruses and dance airs (Gluck) ; — 3° March to the Scaffold, excerpt from the Fantastic Symphony (Berlioz) ; — 4° Prayer from Moïse (Rossini) ; — 5° Overture Der Freischütz (Weber) ; — 6° Hymn to France, chorus (Berlioz), words by Auguste Barbier, composed for this special occasion, and performed for the first time ; — 7° Prayer from La Muette (Auber) ; — 8° Chorus from Charles VI (Halévy) ; — 9° Song of the French Workers (Méreaux) ; — 10° Finale from the Symphony in C minor (Beethoven) ; — 11° Chorus of the blessing of the daggers, from the fourth act of Les Huguenots (Meyerbeer) ; — 12° Hymn to Bacchus, from Antigone (Mendelssohn) ; — 13° Funeral oration and Apotheosis, finale with chorus and two orchestras, from the Funeral and Triumphal Symphony, composed for the transfer of the remains of the victims of the July revolution and the inauguration of the Bastille column (Berlioz). The trombone solo will be played by M. Dieppo. The concert will begin at one o’clock in the afternoon.

Two days before the performance, the massed vocal and instrumental forces will assemble in the building of the Champs-Élysées for one final general rehearsal, which after these preparatory studies cannot fail to go perfectly. M. Tilmant has agreed to serve as my deputy conductor, and the various artists I mentioned above will remain in charge of the groups of instrumental players and singers they will have rehearsed. Finally, the performance will take place on Thursday 1st August, and in the light of this imposing deployment of musical forces, the zeal and goodwill displayed by all, and the composition of the programme, it will live up worthily to general expectations and be a landmark in the annals of art in Paris.

The second day will be filled only with instrumental music, and under the direction of Strauss an orchestra of four hundred musicians will perform overtures, waltzes, polkas and quadrilles that are so close to the heart of that section of the public which is terrified of great music.

H. BERLIOZ.

[See below the poster of the first concert of the Festival conducted by Berlioz.]

Journal des Débats, 2 August (p. 3)

— The great concert of the festival took place today [1st August], under the direction of M. Berlioz, with a success that exceeded all expectations. A huge audience, at once attentive and enthusiastic, performances of almost unbelievable precision and splendour, when one reflects that there were 1022 musicians, made this solemn occasion one of the finest and most imposing that can be cited in the annals of art. The pieces which made the greatest impression were the Prayer from Moïse, the chorus of Les Huguenots, the Hymn to France by M. Berlioz, the last stanza of which was greeted with a veritable explosion of applause, and the song from Charles VI by M. Halévy, which was encored. The receipts amounted to 37,000 fr. His Royal Highness the Duke of Montpensier occupied one of the boxes reserved facing the performers.

The second day of the festival will take place next Sunday [4 August], at one o’clock. A dance orchestra of four hundred musicians will perform, under the direction of M. Strauss, overtures, quadrilles, waltzes and polkas. So that the entry to this final popular festival should be within the means of a large number of people, no distinction has been made between the seats, and the price of a ticket has been fixed at 2 francs.

Revue et Gazette Musicale, 4 August (in French)

FESTIVAL OF INDUSTRY.

(1st day)

This solemn and memorable occasion finally took place last Thursday (1st August), in the presence of an innumerable crowd.

The orchestra and the chorus, placed on an immense amphitheatre, suggested by themselves to the eye the magic impression of a vast concert-hall.

In front, arranged in eight rows, all our famous singers and the finest choristers from our royal theatres stood out conspicuously: sopranos and contraltos in the first four rows, then the tenors and basses.

Behind stood the orchestra, M. Berlioz at its head, with on his left the first violins, on his right the seconds, and behind him the mass of wind instruments; a vast network of lower strings and double-basses provided support to the whole body. Let us not forget a group of harps at the front of the orchestra.

Next to Berlioz stood Tilmant as second conductor; as chorus masters Messrs. Banderali, Benoît, Laty, Dietsch, Tariot and Lebel, shared the task of conducting the choral forces, and what forces! Bordogni, Ponchard and Poultier were singing from the same desk; next to them you could see Wartel-Schubert, Masset, Mocker and the baritone Tagliafico. Here was Baroilhet with his strident voice, and there Levasseur the satanic bass. Here was Mme Dorus-Gras, the incomparable nightingale, at the head of the sopranos, and there the charming Mme Potier, and not far from them shone that pretty and decorative English lady, Mme Anna Thillon.

And how many illustrious names escape our pen! You might as well enumerate all our Parisian celebrities.

And here, in front of the orchestra, were the leading lights of the artistic and literary world; a little further all the aristocracy of the capital, then facing the orchestra a royal box with as guests the Duke of Montpensier and the city authorities, looking down over an immense crowd.

Everyone exuded an air of joy and satisfaction, everywhere there was no mistaking the legitimate pride of national feeling, and in every heart you could imagine reading the words: « France wanted to have her festival, and with one stroke of her magic wand she has thrown this new challenge to the world. » What other country could have assembled such a galaxy of musical talent? And what other city could provide such an imposing and grandiose spectacle?

Unfortunately the hall could not do justice to such a musical occasion. Instead of a large hut, badly arranged and built in poor acoustic conditions, a real palace would have been required, such as ought to exist in Paris, the capital of the arts.

The orchestra, in particular, did not have the impact that might have been expected from the participation of so many assembled talents.

A spectator was saying that the effect of this orchestra was so mean, that at the end of the hall ‘one seemed to be hearing a few miserable sonatas performed on a bad harpsichord.’ The person who was drawing this bizarre comparison was wearing a long blue coat and a most eccentric hat. At this costume and in particular the exaggerated metaphor you will have recognised the author of Pigeon vole, the maestro Castil-Blaze, jealous of not having invented the festival.

Be that as it may, the finale of Beethoven’s C minor symphony was performed by the orchestra with magnificent ensemble and miraculous perfection.

The choral pieces won general approval, notably the Prayer from Moïse of which one stanza was encored, the benediction of the daggers, a sublime excerpt from Les Huguenots, the performance of which would have been admirable but for a vocal incident which Meyerbeer could not have foreseen in his score; and the fine Apotheosis from Berlioz’s symphony, which provided a fitting crown to the session.

But the piece which was honoured with an encore was the national song from Charles VI:

Never will the English lord it over France!

Composed in a way that was entirely appropriate for the occasion, this chorus made a very powerful impression. A number of Englishmen were reportedly outraged, and malicious public rumour adds that the charming Mme Anna Thillon abstained from taking part in it:

The fatherland is dear to all hearts of good birth!

Could this young singer really wish that the English should rule in France? This may be admissible for English women, when they are pretty, and so long as they accept sharing the empire with our own pretty compatriots.

Two pieces suited to the occasion had been prepared for this festival: one, the Song of the Workmen, by M. Méreaux, had no success at all; the Hymn to Bacchus, by Mendelssohn, suffered the same fate. But it is still an honour to succumb in such fine company.

The Hymn to France, by Berlioz, was more fortunate. The fifth stanza, in particular, with the chorus: God protects France, left a deep impression.

And now honour to the brave and persevering artist, honour to Berlioz, who conceived this great idea and who realised it so well! Honour to all our instrumental celebrities, honour to all our good-looking divas, who came here like ordinary choristers to pay homage to the art of music! Honour also to the immense audience, who rewarded with noisy applause and noble enthusiasm the generous efforts of so many dedicated participants!

The receipts amount to 36,000 fr. (of which 15,000 fr. were taken at the door, between noon and one o’clock)!

Charitable institutions will for their part receive 4,500 fr.

Everyone will thus have benefited from this fine music festival, which will live long in the memories of the wealthy as well as of the poorer classes.

The Times, 5 August

L’Illustration, 10 August (pp. 371-3)

THE GREAT FESTIVAL OF INDUSTRY.

Nine hundred and fifty musicians gathered, drilled and operating simultaneously under the direction and word of a single man! No doubt the mere announcement of such an event was enough to arouse public curiosity, especially when you add that this man, this sole and supreme commander, was going to be M. Berlioz, who is not accustomed to stir himself for a limited purpose, and from whom one knows in advance that nothing but extraordinary things should be expected. Hence more than five thousand bystanders had answered the call of M. Berlioz, yielding to the lure of his monstrous poster. — Nine hundred and fifty musicians! Five hundred and fifty instrumentalists! Four hundred singers! How beautiful this must be!

Be we need to be clear about this. A thousand musicians will make ten times more noise than one hundred, if you hear them in the same venue. This cannot be questioned. But if the size of the venue is increased in the same proportions as the number of performers, it is obvious that in both cases the effect will be the same. Now this is what must naturally happen. A thousand musicians — or nine hundred and fifty — cannot be arranged behind the steps of a horse, as Géronte says. On the other hand, one does not risk the huge expenses which necessarily follow from such a vast deployment of musical forces if receipts are not expected in the same proportion; these can only come from an immense number of listeners, and they need to be accommodated. It can therefore be laid down as a general rule that these great gatherings of voices and instruments, which have to fill with their vibrations an immense space, must produce about the same effect as an ordinary orchestra and chorus in an ordinary space.

On the 4th of September 1842, the statue of Mozart was solemnly inaugurated in Salzburg, the city of birth of this great man. The day after, a funeral service was celebrated in the cathedral, and his Requiem was performed by two thousand eight hundred musicians. This is something very different from the nine hundred performers of M. Berlioz, and in Germany this great festival of industry would look like child-play. I do not know what effect was produced by this vast sound-producing army; but the German journalists who reviewed this ceremony hardly insisted on the noise produced there.

Eighteen months ago, the students of the Orphéon, having come together numbering seven or eight hundred, performed a solemn mass at Notre-Dame. They had less effect than twenty choristers do in the evening at the Opéra-Comique.

It is therefore obvious that the bystanders who had come in droves to the great festival expecting « to be gripped, overwhelmed and shattered by the power of the musical forces deployed », had reckoned without their host, and did not have an exact notion of the immensity of the venue where this « solemn musical occasion » was due to take place. The Opéra uses hardly more than a hundred performers, orchestra and chorus together, and the ground-floor (the orchestra, stalls, boxes and balcony) surely do not contain more than a thousand spectators. But there were ten thousand seats at ground level in the Palace of the Exhibition.

Assuming therefore that the hall, arranged hastily for the performance of the festival, had offered the same acoustic characteristics as the hall of the Opéra, one could reasonably expect a result roughly equivalent to what is achieved at the Royal Academy of Music [the Opéra]: one hundred is to a thousand as a thousand is to ten thousand. But the equation was distorted by a plethora of unfavourable circumstances. There was no proportion between the length of the venue and its width. The ceiling was not high enough to enable the sound to blend and spread properly. The hall consisted in a central nave, and two lateral aisles under which the vibrations were stifled and died out. The ceiling was made only of loose sheets of canvas, and the seats were placed on bare ground, with as result that both above and below the sound waves were absorbed instead of being reflected.

No wonder therefore that the effect of the festival was far more limited than those of ordinary performances. It was inevitable that this would happen; the opposite would have been an inexplicable phenomenon, which would have contradicted violently the laws of acoustic.

But the laws of nature do not admit of any contradiction. This was evident. Rarely has anything so dull, dry and heavy been heard than the sound produced by these four hundred voices and this immense orchestra, and those among the listeners who had foreseen this outcome were forced to admit that it exceeded their expectation. It was as though a malevolent magician had taken delight in silencing the instruments, or that every listener had wax in his ears, as in old times did the companions of Ulysses. The overtures to La Vestale and to Der Freischütz, the March to the Scaffold, and the Symphony in C minor were truly unrecognisable.

The pieces where voices were mixing with the instruments were less completely muffled. The reason is that the chorus was placed in front of the orchestra and was not under the aisle in the nave; consequently there was far more air above it, and it was further away from those loose sheets of canvas which absorbed so completely the vibrations of the instruments. The chorus from Les Huguenots, the prayers from La Muette and from Moïse were less effective than they are at the Opéra, but none the less sufficiently telling for the audience to have been delighted to hear them. The prayer from Moïse, in particular, galvanised the audience which asked for it to be repeated there and then. The national song from Charles VI,

War on the tyrants! Never in France,

Never will the English rule,

received the same distinction, and even stirred the audience to far more noisy demonstrations of enthusiasm. This is because the applause of the public now carried a double meaning, since to musical pleasure were added political passions exacerbated by the news which had just arrived from Tahiti and had been spread by the morning papers. Besides, a rumour had circulated that the ambassador from England was present in the hall. When the orchestra proceeded to comply with the requests of the audience, whose shouts of Bis could have toppled the fragile building, it is said that two English ladies thought it prudent to protest by leaving the hall. Ladies, this is taking touchiness, or perhaps prudence, rather too far!

It would be hard to imagine anything more mediocre and flat that the Song of the Workers, a cantata composed by M. Méreaux for this occasion.

The Hymn to France by Berlioz has far more merit, and ends with a surge of sound which made a deep impression; its effect would have been colossal had it been performed in a more sympathetic venue.

In general the performance deserves nothing but praise. Both orchestra and chorus performed with perfect ensemble, and M. Berlioz wielded the baton of command with uncommon intelligence and energy. But why did he choose as his battle-ground this hideous hut on the Champs-Élysées, so grotesquely dignified with the title of palace? Why had he not requested instead from the competent authorities the magnificent and useless monument called the Panthéon, which meets all the acoustic requirements of which the hall of the exhibition is devoid?

![]()

Front

|

Back

|

© Hector Berlioz Museum

The original copy of the above programme is in the collections of the Hector Berlioz Museum. We are most grateful to the Museum for granting us permission to reproduce a scanned copy of the programme on this page. All rights of reproduction reserved.

This picture is reproduced from l’Ilustration, 10 August 1844 (p. 372), a copy of which is in our own collection.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page. All rights of reproduction reserved. This page created on 15 October 2012, updated on 1 December 2012.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.