![]()

This page is also available in French

![]()

The Paris Opéra has undergone several changes of names and locations since the 1790s: it has been called successively Théâtre de l’Opéra, Théâtre des Arts, Académie Impériale de Musique, and Académie Royale de Musique, and has occupied several venues: Théâtre de la Porte-St-Martin, Théâtre Montansier, the first Salle Favart, the Théâtre Louvois, Le Peletier, Palais Garnier, and the Opéra Bastille.

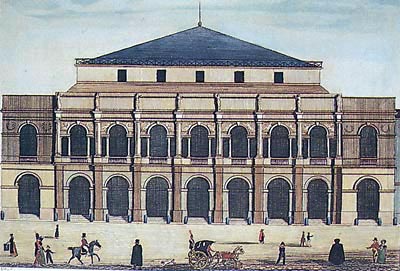

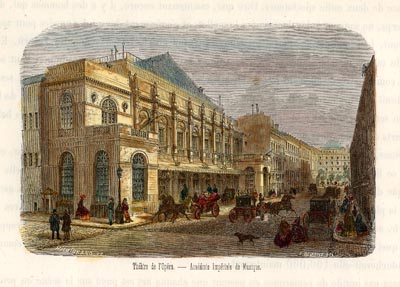

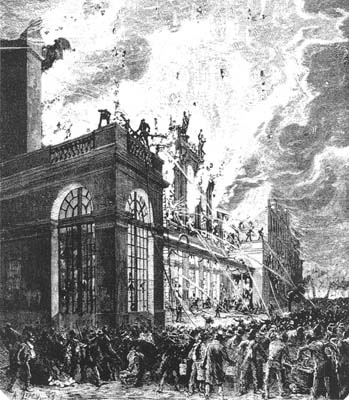

The Paris Opéra that Berlioz knew was Le Théâtre de l’Académie Royale de Musique (the Opéra), known as Le Peletier. It was built in twelve months in the Rue Le Peletier by the architect Debret and opened in 1821; on 6 February 1822 gas was used for the first time to light up stage effects in Aladin ou La Lampe merveilleuse. Fifty years later it was destroyed by a fire which raged for 24 hours on 28-29 October 1873. The ruins were demolished and the ground was sold in 14 lots. The opera house was replaced by the Opéra Garnier.

The Opéra played as central a role in Berlioz’s career in Paris as did the Conservatoire. Almost from the moment of his arrival in Paris in November 1821 his visits to the Opéra had a decisive influence in the shaping of his musical personality, as can be seen already in a letter to his sister Nanci dated 13 December 1821 where he recounts the impact of a performance of Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride. This was many years before his discovery of Beethoven in 1828, which opened up to him the possibilities of symphonic music. It was at the Opéra that he experienced for the first time the music of Gluck his idol, Spontini and others, the singing and acting of the great Mme Branchu, which lingered in his memory, the magnificence of the spectacle on stage, the sound of a large and professional orchestra, with whose musicians he soon developed close personal relations. Berlioz’s Memoirs give detailed evidence on these early impressions (see especially chs. 5, 13, 15).

Success for a composer in Paris went through success at the Opéra: this was to prove a stumbling block for Berlioz, who was never able to achieve as a composer of operas the success and influence enjoyed by Rossini in the 1820s and above all by Meyerbeer, who dominated the operatic scene in Paris from 1831 till after his death in 1864. Meyerbeer’s career at the Opéra was a succession of triumphs which made him the wealthiest composer of his time: Robert le Diable (November 1831), Les Huguenots (February 1836), Le Prophète (April 1849), Le Pardon de Ploërmel (April 1859) and the posthumous L’Africaine (April 1865). Berlioz by contrast had to struggle throughout his career to gain acceptance. An attempt to get his early opera Les Francs Juges accepted for performance was brusquely turned down by the conductor Rodolphe Kreutzer in 1826 (Memoirs ch. 11). A performance of his fantasia on Shakespeare’s Tempest on 7 November 1830 was a fiasco (Memoirs ch. 27). After his return from Italy Berlioz eventually secured with powerful backing acceptance of his opera Benvenuto Cellini, but the organised hostility encountered by the work at its première on 10 September 1838 was one of the major setbacks in Berlioz’s career (Memoirs chapter 48). After a few performances the work was dropped, never to be staged again in Paris in Berlioz’s lifetime (it was revived by Liszt in Weimar in 1852 and 1856 in a modified version).

Thereafter Berlioz’s role at the Opéra was at best intermittent: a performance of the Symphonie Funèbre on 1st November 1840, the writing of recitatives and the orchestration of a ballet piece for a production in French of Weber’s Der Freischütz in 1841 (Memoirs ch. 52), a grand festival concert on 7 November 1842 (Memoirs ch. 51, which conflates it with the performance of 1840). In 1861, and again in 1866, he supervised productions of Gluck’s Alceste (there is a detailed account of the 1861 performance in À Travers Chants).

But no more than at the Conservatoire was Berlioz able to achieve the permanent position he needed and deserved. In 1847 there was talk by the new directors Roqueplan and Duponchel of giving Berlioz a role as conductor, but the hypocrisy of the scheming pair was soon exposed (Memoirs ch. 57). In 1841 Berlioz had started work on a new opera, La Nonne Sanglante, on a libretto by the influential Eugène Scribe, but after years this was eventually dropped. The knowledge that the doors of the Opera were closed to him long discouraged Berlioz from beginning the writing of his masterpiece Les Troyens, which only the Opéra could stage adequately (Memoirs chapter 59, dated 18th October 1854). Eventually he was persuaded by Princess Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein to write the work (1856-8), but was unable to get Napoleon III interested in it. As a result Berlioz had to settle for an imperfect production in 1863 at the smaller Théatre Lyrique, in a truncated version with numerous cuts (Memoirs, Postface of 1864), though it should be said that Berlioz’s account in the Memoirs does less than justice to Léon Carvalho, the director of the Théâtre-Lyrique, without whom the work would not have been performed. This, and the failure of the publisher Choudens to honour his undertaking to publish the full score of Les Troyens, cast a melancholy shadow over the end of Berlioz’s career.

![]()

Unless otherwise specified, all pictures on this page have been scanned from engravings, books and newspapers in our own collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

A copy of this engraving is in the library of the present Paris Opéra.

The above engraving dates from 1861.

This engraving was published in the Univers illustré, 15 November 1873.

We are most grateful to M. Laurent Ludart who sent us this picture.

This 1850 engraving is by B. Metzeroth.

This engraving was published in the Univers illustré, 15 November 1873.

We are most grateful to M. Laurent Ludart who sent us this picture.

This engraving, with the above title, was published on page 444 of the 8th November 1873 issue of the Illustrated London News.

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.