Unless otherwise stated all pictures on Berlioz Photos pages have been scanned from engravings, paintings, postcards and other publications in our collection. All rights of reproduction reserved.

This page includes image of the following: Napoleon Bonaparte, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, and Empress Eugénie.

![]()

The above postcard from our collection reproduces a painting by Baron François Gérard (1770-1837) that shows the emperor in his coronation costume, in 1805.

Napoleon Bonaparte was born on 15 August 1769 in Corsica and died on 5 May 1821 in captivity on the remote Atlantic island of St. Helena (see below). The young Berlioz grew up in a world dominated by this commanding figure, whose armies overran Europe and established France as the leading power of the day. Berlioz’s uncle Félix Marmion served as an officer in the French army and had many stories to tell about his own part in the Napoleonic wars, as Berlioz recalled in his Memoirs (chapter 3). In the 1820s, Lesueur, his teacher at the Conservatoire, was himself an admirer of Napoleon and had much to say about the emperor and the support he had given Lesueur in his own career (Memoirs chapter 6; Soirées de l’orchestre 20th evening). In his biographical sketch of Spontini Berlioz also recalled how Napoleon and the empress Joséphine had assisted the composer in the writing of his masterpiece the opera La Vestale. Berlioz thus grew up in an environment which led him, and many other contemporaries such as Victor Hugo, to think of Napoleon as a heroic, powerful and beneficial figure: his writings — his books, his articles, his correspondence — are full of references to the emperor, and they are invariably positive in tone. In one of his letters he apostrophises Napoleon: ‘O Napoleon, Napoleon, genius, power, strength, will!… Why did you not crush in your iron hand another fistfull of this human vermin!…’ (CG no. 216, 12 April 1831)

In his own travels Berlioz was often conscious of following in the footsteps of Napoleon, as in his trip to Italy in 1831-2. While there he toyed with the idea of visiting Corsica (where Napoleon was born) and the island of Elba (where Napoleon was detained for a period), though those visits did not take place. On his return journey to France in May 1832, and on the way to Milan, he passed through the plain where Napoleon had defeated the Austrian army at the battle of Lodi (10 May 1796); this prompted him to sketch a plan for a military symphony on the return of the French army from Italy. The work was not completed but material from it may have been utilised later in the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale of 1840. While still in Rome he had been occupied with a cantata on the death of Napoleon to a poem by Béranger (Le Cinq mai), as he recalled later (CG no. 449; Débats 23 July 1861, reproduced in À Travers chants). He may have started composing it earlier, but in the event the work was only completed several years later, in 1835 (CG no. 454), when it received its first performance (22 November). In his tour of Germany in 1843 he performed the cantata in a number of cities (Dresden, Hamburg, Berlin, Hanover, Darmstadt). As Berlioz remarked on the occasion of his visit to Dresden, it was always well received, ‘as the memory of Napoleon is almost as dear to the German people as it is to the French’.

Berlioz’s trip to Russia in 1847 brought back further Napoleonic memories, as he travelled through frozen landscapes and recalled the hardships of the French army retreating from Moscow (Memoirs chapter 55). In Moscow Berlioz saw the French cannons captured by the Russians from the retreating French army.

It was perhaps appropriate that the name of Napoleon should also have been associated with the very last public engagement in Berlioz’s career in August 1868: when he travelled to Grenoble to take part in adjudicating a choral competition, the event coincided with the inauguration of a statue of Napoleon which Berlioz did attend (CG no. 3373).

This early 20th century postcard in our collection reproduces a contemporary engraving of Napoleon in army uniform.

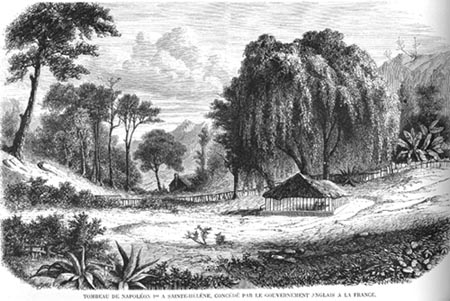

The above picture is from an 1858 issue of L’Illustration in our collection.

The Moniteur of 10 June 1858 announced that the ownership of Longwood and the Emperor’s Tomb had as of then been conceded by Britain to France. The remains of the emperor had already been transferred to France and reburied in the Invalides in December 1840. To mark the occasion Berlioz had included Le Cinq mai in his concert of 13 December, now with the subtitle Chant sur la mort de l’Empereur Napoléon.

This picture, from an 1848 issue of L’Illustration in our collection, shows Louis Napoleon Bonaparte as the Prince-President of the short-lived republic (1848-1852).

A nephew of Napoleon I, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte grew up in the belief that it was his birthright to succeed to the position previously held by his uncle. After two unsuccessful coups in 1836 and 1840 he found his opportunity with the revolution of 1848, and on 10 December 1848 was elected Prince-President of the new republic. He then carried out a coup on 2 December 1851, as a result of which Victor Hugo went into exile; he proclaimed himself Emperor in November 1852 and sanctioned his position with a plebiscite on 20-21 December. The following year he married Eugénie (20 January 1853) and ruled France as emperor until expelled in 1870. He died on 9 January 1873 in exile in England.

Politically Berlioz openly supported the government of Napoleon III, and hoped that the new emperor would support music and the leading composers of the day in the same way as his uncle had done with Lesueur and Spontini; but unfortunately Napoleon III had no interest in music. Berlioz was well aware of this, though this did not prevent him from trying repeatedly to win his support for his own musical undertakings, undeterred by constant failures over more than a decade. Late in 1852 he drew up a plan for the organisation of a new imperial chapel for the new regime, in which he himself might have an important role; he had no success, and the post went to Auber (the text of his proposal is in CG vol. IV pp. 727-9). His Te Deum, substantially completed by 1849, was as yet unperformed; he hoped to have it included in some imperial ceremony (cf. e.g. CG no. 1536, 29 November 1852). One such occasion was the wedding of the Emperor with Eugénie in January 1853, but, as he wrote to his sister Adèle after the event, ‘the emperor is not in the least interested in these musical questions’ (CG no. 1574, 5 March 1853). The Te Deum had to wait till the Exhibition of Industry two years later to be performed at Saint-Eustache (30 April 1855). By the summer of 1854 Berlioz had written a cantata in praise of the emperor, l’Impériale, intended for use on the occasion of the birthday of Napoleon I on 15 August; he wrote the work apparently on his own initiative, and not in answer to any official commission (CG no. 1773). In the event the work had to wait till late in 1855 for performance at two large concerts (15 and 16 November), which Berlioz was asked by the imperial court to organise at very short notice to close the Universal Exhibition. After the concerts Berlioz was informed that his name was being put forward for the rank of Officer of the Légion d’honneur (CG no. 2057); in the event he only received the award in August 1864.

But the greatest disappointment was yet to come. In 1856 Berlioz had been persuaded after much hesitation to undertake the composition of his great opera Les Troyens, and by 1858 the work was substantially complete (though it was to undergo much subsequent revision). It was destined for the Paris Opéra, the only opera house in France with the resources to perform it adequately. But to achieve this needed the active support of the Emperor. The melancholy story of Berlioz’s attempts to interest the emperor (and the empress) in the work is followed in detail elsewhere on this site. From the point of view of musical history the failure of Napoleon III to support the work had many negative consequences: for the opera itself, which took many decades to recover from the mutilated condition in which it was first performed in late 1863 at the Théâtre Lyrique; for the composer himself, whose morale never recovered; and for the posthumous reputation of Napoleon III. It was in his power to support the greatest French composer of the day, but instead he has gone down, as far as music is concerned, as a Philistine, in striking contrast to the enlightened German princes such as the Grand-Duke of Weimar, who had vainly tried to persuade him to support Les Troyens and could not understand his attitude (CG nos. 2724, 2798, 2805, 2857).

A letter of Berlioz to his friend Humbert Ferrand sums up his contradictory feelings towards Napoleon III (CG no. 1871, 2 January 1855):

I am an imperialist through and through; I will never forget that our emperor has liberated us from the filthy and stupid republic! All civilised men must remember this. He has the misfortune of being a barbarian as far as art is concerned, but then this barbarian is a saviour — and Nero was an artist, — There are minds of every possible variety.

The above picture, from an 1853 issue of L’Illustration in our collection, shows the Emperor and Empress Eugénie on their wedding day on 30 January 1853.

The above painting is by Franz-Xavier Winterhalter (1805-1873). The image is courtesy of the Grand Ladies website.

In his attempts to interest Napoleon III in Les Troyens Berlioz found the emperor particularly difficult to approach (CG nos. 2275, 2277, 2279). As he result he tried on several interests to approach the empress Eugénie instead; a number of letters refer to these meetings and give a description of the empress (CG nos. 2219, 2222, 2256, 2267, 2275). In the end he was no more successful.

![]()

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the texts and images on Berlioz Photo Album pages.

All rights of reproduction reserved.