![]()

This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz’s stay in Milan in 1832 was only a brief stop on his return journey from Rome to France. While still in Florence he envisaged staying in Milan only a week at most (CG no. 270, to Ferdinand Hiller, 13 May, from Florence), but in the end the stay was reduced to a few days, from 20-23 May. The day after his arrival in the city he wrote to his mother (CG no. 271, 21 May):

[…] I only stayed three days in Florence where I came across many acquaintances of mine.

I am here only since yesterday, and I have already received two invitations. Milan is a proper large-scale city, it is almost like Paris. I am now closer to you by 180 leagues. I do not know how long I will be staying, so do not write to me here. I was hoping to find at the post office a letter from Adèle, why was it not there?… […]

The following day he attended a performance at the opera, as emerges from a letter to Horace Vernet dated 23 May, which unfortunately is known only from a summary of its contents, except for a passage on his impressions of the opera-house (CG no. 272bis [vol. VIII]):

[…] I will not tell you anything about the score [Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’amore]. Brass, bass drum, platitudes, from start to finish. In truth it would be a great pity to give performances of good music to such a public. People talk loud as at the Stock Exchange and the dilettanti provide a pretty accompaniment by hitting the floor with their walking-sticks; they may find that very pleasant but it put me to flight in a rage. I would rather keep animals in a farm or measure out cloth in a shop in rue St Denis than be obliged to write for these brutes. What a humiliation! Poor music! […]

A letter to his friend Humbert Ferrand dated 25 May, by which time Berlioz was in Turin and on his way to France, gives a similar account, and also introduces the Napoleonic theme that haunted Berlioz on several occasions during his Italian trip (CG no. 273):

[…] How magnificent and rich are the plains of Lombardy! They awoke in me painful memories of our days of past glory, ‘like a vain dream that has vanished’.

In Milan I heard for the first time an energetic orchestra; this is beginning to look like music, at least as far as performance is concerned. The score of my friend Donizetti can join those of my friend Paccini and my friend Vaccaï. The public is worthy of such productions. People talk loud as at the Stock Exchange, and the sound of men’s walking-sticks on the floor provides an accompaniment that is almost as noisy as that of the bass drum. If ever I write for these brutes, I will deserve my fate; there could hardly be a more lowly one for an artist. What a humiliation! […]

The account Berlioz gave later in his Voyage en Italie in 1844, which was eventually reproduced in the Memoirs (chapter 43), confirms the impressions he gave in his letters at the time:

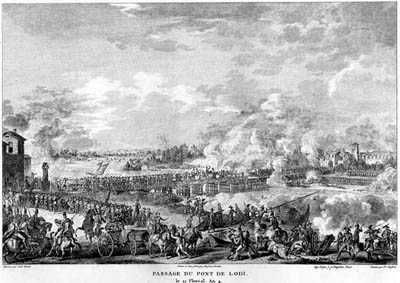

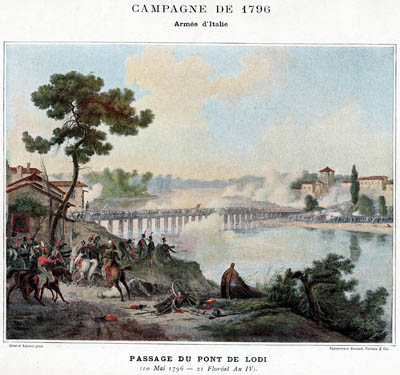

[…] While going through Lodi I did not fail to visit the celebrated bridge. I thought I could still hear the deafening thunder of Bonaparte’s guns and the screams of the Austrians in full flight.

The weather was wonderful, the bridge was deserted, and there was only an old man, sitting on the roadway, who was fishing with a rod. — Saint-Helena!…

On arriving in Milan, I felt out of a sense of duty that I had to go and see the new opera. They were performing at the Cannobiana at the time Donizetti’s l’Elisir d’amore. I found the hall full of people who were talking loud and turning their backs on the stage. This did not prevent the singers from gesturing and singing their lungs out; at least that is what I had to believe at the sight of their wide-open mouths, since the noise of the spectators made it impossible to hear any sound except that of the bass drum. In the boxes people were playing games, having dinner etc., etc. As a result, despairing of being able to hear a note of the score, which was new to me at the time, I left. But apparently the Italians do on occasion listen to the music, as several people have assured me. At any rate for the Milanese, as for the Neapolitans, the Romans, the Florentines and the Genovese, music means a well-sung aria, or a duet, or a trio, but no more; beyond this their only reaction is one of aversion or indifference. […]

In the above citations from his correspondence and the Memoirs, Berlioz alludes briefly to an important episode in the Napoleonic wars, the battle fought and won by Napoleon against the Austrian army at the bridge of Lodi, south-east of Milan, on 10 May 1796 which gave him control of Lombardy. It is known further from a sketchbook of 1832-6 (Holoman Catalogue no. 62) that his passage there suggested to Berlioz the idea of a military symphony on the return of the French army from Italy; the work was planned in two parts, a farewell to the fallen soldiers from the height of the Alps, followed by the triumphant entry of the victors in Paris. The idea took shape years later in the Funeral and Triumphal Symphony of 1840.

Through much of his trip to Italy Berlioz was haunted by the memory of Napoleon, as references in the correspondence suggest (see esp. CG nos. 216, 230, 244). In Florence in April 1831 he witnessed the funeral of a nephew of Napoleon (CG no. 216; Memoirs ch. 35). On his return journey in 1832 he seriously considered visiting Elba and Corsica ‘to gorge himself with Napoleonic memories’, but the plan eventually had to be called off (CG nos. 265, 266, 270). It is also known from a casual allusion in a feuilleton of 1861 that it was in Rome that Berlioz accidentally found the refrain that enabled him to complete his cantata Le Cinq Mai on the death of Napoleon (Journal des Débats, 23 July 1861, reproduced in A Travers Chants).

Though he never returned to Milan, Berlioz did subsequently have relations with musicians and publishers in the city, as outlined in the page Berlioz in Italy.

![]()

The following pictures have been scanned from engravings and postcards in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

It is very likely that Berlioz had paid a visit to la Scala during his sojourn in Milan; see for instance his feuilleton of 6 February 1853 in the Journal des Débats when he writes about the enormous size of the theatres of la Scala and the Cannobianna in Milan, and that of San Carlo in Naples.

The above postcard reproduces an engraving dated 1700.

The above postcard reproduces a mid-19th century engraving.

English translation of the caption below the engraving:

The Crossing of the Lodi Bridge

(10 May 1796 – 21 Floréal Year IV)

![]()

The Berlioz in Italy pages were created on 7 December 2003; this page created on 1 May 2012, updated on 1 November 2012. Revised on 1 June 2024.

© (unless otherwise stated) Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.