![]()

Introduction

The concert in 1863

Berlioz’s speech

Illustrations

This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz only gave one concert in Strasbourg, in June 1863 and late in his career. He had previously given concerts in several cities in France – Marseille and Lyon in 1845, Lille in 1846, Bordeaux in 1859 – but for most of his career Strasbourg was not part of his musical horizon. Berlioz’s connection with Strasbourg was a by-product of his association with Baden-Baden, across the Rhine in the Black Forest, to which he went every summer from 1856 to 1863 to give a concert. Strasbourg was not far away and a natural stop on the way to or from the fashionable resort, and musicians from Strasbourg participated in events in Baden-Baden.

It was on his return from one of his concerts in Baden-Baden (August 1858) that Berlioz, accompanied by his second wife Marie Recio, made his first recorded visit to Strasbourg. They were invited here by Jean-Georges Kastner (1810-1867) and his wife to stay at their house. Berlioz and Kastner, a native of Strasbourg, had known each other for a long time – the earliest letters from Berlioz to Kastner date from late 1838 and 1839 (Correspondance Générale nos. 615, 629, 662, hereafter CG for short). In the first of these Berlioz congratulates Kastner on his Bibliothèque Chorale which had just been published, and which Berlioz noticed favourably on 22 January 1839 in the Journal des Débats (Critique Musicale IV pp. 14-15, hereafter CM for short). Kastner was the author of numerous theoretical and practical manuals on music, including works on instrumentation, on which Berlioz commented favourably on several occasions (Journal des Débats, 14 January 1838, 18 October 1840, and esp. 2 October 1839 at length on the Cours d’instrumentation; CM III p.;;368; IV PP. 165-72 and 386); they stimulated Berlioz to write his own Treatise on Instrumentation several years later, in which Kastner’s earlier Traité is mentioned with praise. Kastner was also a composer of merit, and Berlioz mentioned or reviewed a number of his works (Journal des Débats, 16 February 1840 on the opera Beatrice; 1 July 1841 on the comic opera La Maschera; 6 December 1844 on the opera Le Roi de Juda; CM IV pp. 261, 517-19 and V, pp. 575-9). Berlioz continued to mention Kastner favourably in his feuilletons of the 1850s (see Journal des Débats, 17 January 1851; 19 October 1855; 9 October 1858).

Both Kastner and his wife – she was an excellent musician in her own right – were present at the concert in Baden-Baden in August 1858 and attended two of the rehearsals. Berlioz describes in a letter to his uncle the warm and lavish reception he and Marie were given during their two-day stay in Strasbourg (CG no. 2308). Back in Paris Berlioz had the joy of reading an enthusiastic article by Kastner on Roméo et Juliette, which was published on 12 September in the Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris – excerpts from the work had been performed in Baden-Baden. He wrote immediately to thank Kastner (CG no. 2312) and a few days later actually sent him the autograph of the work with an inscription (CG no. 2313, 17 September):

Autograph score presented to my excellent friend Georges Kastner.

You will forgive me, my dear Kastner, for giving you such a manuscript. It is covered with wounds as a result of its campaigns in Germany and Russia. It is like the standards that return from wars, more beautiful (as Victor Hugo says), when they are torn.

Kastner responded with a warm letter in which he describes the autograph in detail, and adds: “my wife and I cannot tire of admiring this priceless manuscript; it would be cited as a model of musical calligraphy were it not that the admiration it inspires on far more serious grounds prevents one from drawing attention to this kind of distinction” (CG no. 2314). Berlioz and Kastner remained in touch subsequently – Kastner, like Berlioz a member of the Institut (cf. CG nos. 2428, 2443), was resident in Paris. In 1862 Berlioz offered Kastner a copy of the vocal score of Les Troyens with a dedication (CG nos. 2591, 2592, 2611).

It was the same concert in Baden-Baden in August 1858 that brought together Berlioz and another musician from Strasbourg, the composer and critic François Schwab (1829-1883). Unlike Kastner, Schwab’s career was firmly rooted in his native city where he was influential in musical circles. He was a frequent contributor to the Courrier du Bas-Rhin and to the Journal d’Alsace. On 4 September 1858 he published an enthusiastic article on Berlioz in the journal l’Illustration de Bade, for which Berlioz thanked him, praising his perceptiveness (CG no. 2311, 7 September). In his article Schwab used the striking phrase “a magnetic steel sceptre” (un sceptre d’acier aimanté) to describe Berlioz’s baton and conducting style, a phrase which delighted Berlioz (the phrase was used, perhaps not coincidentally, by Kastner himself in his letter thanking Berlioz for the gift of the autograph manuscript of Roméo et Juliette: CG no. 2314, referred to above). Berlioz repaid the compliment by including a piece by Schwab – a fantasia for clarinet – in his concert in Baden-Baden the following summer; it was to be played by the able clarinettist Wuille from Strasbourg (CG no. 2391, 12 August 1859). The following year Schwab wrote another appreciative review of the next concert in Baden-Baden, which delighted Berlioz: “my musical career would not have been so arduous if there had been as many intelligent and warm-hearted critics as yourself” (CG no. 2514, 4 September 1860). Evidently Schwab, like Adolphe Samuel in Brussels, was anxious to bring his hero to conduct his own music in Strasbourg. The occasion came a few years later. Schwab wrote a warm review in the Courrier du Bas-Rhin of the first performance of Béatrice et Bénédict in Baden-Baden in August 1862; the choral parts were sung by singers from the Strasbourg theatre (CG nos. 2589, 2604, 2612, 2632). Schwab took the opportunity to invite Berlioz to come and conduct L’Enfance du Christ the following year (June 1863) on the occasion of an annual choral festival (the meeting of the Sociétés chorales d’Alsace at the Festival du Bas-Rhin), which Berlioz was happy to accept (CG no. 2666, 26 October 1862 – an earlier reply of Berlioz was apparently lost in the post). Over the coming months Berlioz was in regular correspondence with Schwab and gave a series of practical recommendations, on the choice of players (for the trio for two flutes and harp), singers, the layout of the forces, the rehearsals needed, and various points of detail (CG nos. 2666, 2701, 2717, 2721, 2723, 2732, 2739). He also sent Schwab a copy of the vocal score of Béatrice et Bénédict: Schwab cut out from a letter of Berlioz the dedication and signature that Berlioz intended to write and placed it in his copy, so as to have it in the master’s own hand! (CG no. 2721, 3 May 1863)

![]()

Berlioz had hoped to visit Strasbourg on his way back from Löwenberg in Silesia in April in order to rehearse the chorus prior to the performance in June; in the event his stay in Silesia was prolonged and he had to return directly to Paris (CG nos. 2711, 2713, 2717). In the meantime chorus and orchestra were studying their parts.

Berlioz left Paris for Strasbourg at 8 o’clock in the evening on Monday 15 June (CG no. 2732); although he does not specify this, he will have travelled by train departing from the Gare de l’Est, and arrived in Strasbourg the following morning. He stayed in Strasbourg with the musician Jean Becker who had invited him at his house at no. 103 Grande Rue, not far from the centre of the city (CG nos. 2721, 2722, 2723bis, 2732, 2738, 2739). He took charge of the rehearsals, first the singers on 17 and 18 June, then the general rehearsal on the 20th. On the evening of the 20th he attended a reception at Kehl, on the German side of the Rhine (see below). On the 21st there was a meeting of the assembled choral societies, 106 in all with 2000 singers on stage, and in the evening a banquet offered by the Préfet at the Hôtel de la Ville de Strasbourg. On Monday 22 June, the day of the concert, the morning was taken up by a competition of choral societies, with Berlioz as the president of the jury, while the concert itself was in the afternoon at 3 o’clock. The concert was in two parts. The first comprised Beethoven’s seventh Symphony, the cantata Les Voix de la lyre by Schwab, Weber’s Euryanthe overture, and excerpts from L’Océan, an oratorio by Elbel (Berlioz was not involved in this part of the concert, which he never mentions in his letters). The second part was devoted to L’Enfance du Christ, conducted by Berlioz. The chorus numbered 460, and the orchestra no less than 90. The soloists were: Maria Scheffer (Marie), Klein (Hérode), Morini (Récitant) and Battaille (Père de famille), who had sung at the first performances of the work in December 1854 and was highly regarded by Berlioz (CG nos. 1824, 1830, 2701, 2717, 2721).

For the purposes of the concert a large temporary hall had been specially constructed in Place Kléber, the largest square in the city and near its centre. The hall had an imposing façade en trompe l’œil, surmounted by a statue of Saint Cecilia, and could accommodate an audience of no less than 8000. Although it was dismantled after the concert, its appearance was preserved in a contemporary engraving.

The size of the hall and the unusually large forces deployed for such intimate music had been a source of worry to Berlioz. In a letter to Schwab of 28 May, after recommending that the chorus “Que de leurs pieds meutris” in Part III be sung softly, he adds “But we are worrying about niceties in asking for nuances of this kind; from what you are saying and what I have heard from M. Méry about the immensity of the hall, it is clear that all will be lost and that hardly anything will be audible. It would have been just as well to make music in a public square” (CG no. 2732). In the end Berlioz’s fears proved unfounded, as he wrote in the Postface of the Memoirs the following year:

A vast hall with a capacity of 6000 had been built [Berlioz’s letters give the figure of 8000 or 8500, cf. CG nos. 2741, 2743, 2745]. There were 500 performers. It could have been thought that this oratorio, written almost throughout in a tender and gentle style, would be difficult to hear in this vast building. To my great surprise it moved the audience deeply, such was its concentration, and the unaccompanied mystical chorus at the end « O mon âme » moved many to tears. How happy I am when I see my audience in tears!... This chorus does not have anything like the same impact in Paris, where it is in any case always badly performed.

Letters of Berlioz after his return to Paris later in the month give more details (none survive from the time of his stay in Strasbourg). On 27 June he writes to Humbert Ferrand (CG no. 2741; cf. also nos. 2742, 2743, 2745):

I am just back from Strasbourg, shattered but deeply moved... L’Enfance du Christ performed in front of a whole people has had an immense impact. The hall, specially built on Place Kléber, had a capacity of 8500 people, and yet everything was clearly audible. People wept, applauded, and several pieces were interrupted by spontaneous acclamations. You cannot imagine the impression made by the mystical chorus at the end: « O mon âme! ». That was in truth the religious ecstasy I had dreamed of and experienced while writing it. An unaccompanied chorus of 200 men and 250 young women, who had rehearsed for three months. The pitch did not drop by even a quarter tone. These things are unknown in Paris. At the last amen, at this pianissimo which seems to vanish into a mysterious distance, there was an ovation without equal, sixteen thousand hands were clapping. Then of torrent of flowers... and demonstrations of every kind. I was looking for you in this crowd.

How long Berlioz stayed on in Strasbourg after the concert is not known; at any rate he was back in Paris by 27 June, as the letter to Ferrand shows. Schwab had written an appreciative article on L’Enfance du Christ which first appeared on 19 June, before the concert, in the Courrier du Bas-Rhin; he also published in the same journal a review of the concert immediately after, on 23 June. On his return to Paris Berlioz busied himself with trying to ensure both articles were reproduced in the Paris press in their entirety (CG no. 2744, 29 June), as eventually happened. He was also gratified by the generosity of the committee of the Strasbourg Festival, which gave him an additional gratuity of 1000 francs (CG no. 2747, 4 July). But beyond the mention in the Memoirs (above) he did not seek to publicise the success of the trip as he would probably have done earlier in his career. All the same, the Strasbourg performance lingered in his memory. In April 1867, writing to Estelle Fornier about a report of the performance of L’Enfance du Christ in Lausanne, he comments “I have not heard this work since Strasbourg 3 years ago; but there it was majestic, and Germany and France were holding hands. I wish you had been in the audience on that occasion” (CG no. 3232).

In November 1863 there was talk of staging Les Troyens in Strasbourg, but nothing came of the plan (CG no. 2789).

![]()

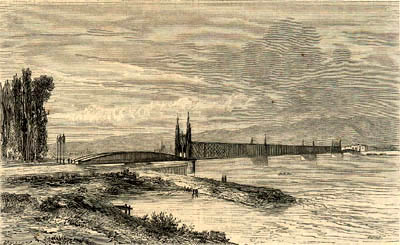

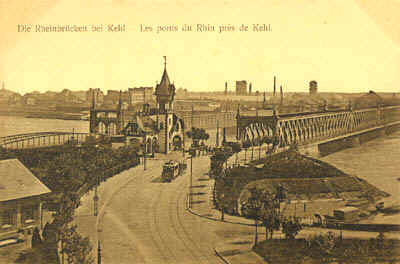

During the weekend prior to the concert, on 20 June, Berlioz and two other guests (Friedrich Kücken, Kapellmeister of Schwerin, and Franz Abt, Kapellmeister of Brunswick) were invited by a group of German choral societies to a celebration at Kehl, on the German side of the Rhine opposite Strasbourg, for which they crossed the new bridge over the river (it had been constructed in 1861). Berlioz gives a short account of this ceremony in a letter to his brother in law Camille Pal (CG no. 2745, 1 July):

The Germans had wanted to honour me before the French did. When they knew that I was in Strasbourg, the societies of Karlsruhe, Bade, Mannheim, Heidelberg etc. which had gathered in Kehl invited me to come and hear them. They welcomed me on the Rhine bridge with an ovation, cannon fire, military music etc. I was led to the church where a chorus of welcome was sung [Kalliwoda’s Chant allemand], there was much applause and numerous toasts, and speeches were made. Then they led me back to the French side of the river in the same style.

Neither here nor in his Memoirs does Berlioz make any explicit mention of the short speech which he delivered on this occasion, and which has survived in two autograph drafts, one of which is reproduced below. The speech is worth quoting in full:

Sir

My colleagues and I were very happy to respond to the invitation from the city of Strasbourg, and we regret that we were unable to do more to assist it in its fine enterprise. You have said it, sir: under the influence of music the spirit soars and ideas expand, civilisation progresses, and national animosities disappear. See how today France and Germany are moving towards each other! The love of art has brought them together, and this noble love will do more for their complete union than this wonderful bridge over the Rhine and all the other lines of fast communication that have been established between the two countries.

The great poet said: “The man that hath no music in himself .../ Is fit for treasons, stratagems and spoils .../ Let no such man be trusted” [The Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene 1, lines 83-88]. No doubt Shakespeare was taking advantage there of the licence granted to poets to exaggerate. But the observation nevertheless demonstrates that though this may be excessive as far as individuals are concerned, it is much less so concerning peoples, and one must now recognise that where music ends barbarism begins.

To the very civilised city of Strasbourg, to the very civilised cities of France and Germany which have joined with her to bring about the project of her magnificent festival!

The speech is loaded with literary allusions. In addition to the quotation from Shakespeare, the phrase “civilised city/cities” alludes to Berlioz’s own writings. In 1852 he had dedicated his Soirées de l’Orchestre “To my good friends the artists of the orchestra of X***, a civilised city” – unidentified, but significantly located in northern Germany – while Les Grotesques de la Musique was dedicated in 1859 “To my good friends the artists of the chorus of the Opéra in Paris, an uncivilised city [ville barbare]”. The speech expressed sentiments that were dear to Berlioz. In his reference to the bridge over the Rhine he was celebrating the technical progress of the age and the development of communications from which he had benefited in his career of musical travels across Europe. Above all Berlioz, who once described himself as “a musician three-quarters German”, showed himself to be a true ‘musician without frontiers’ who rose above national prejudices and could not but deplore the gathering national animosities of his time. This was the message he emphasised on many occasions, such as in his report on the celebrations at Bonn in 1845 in honour of Beethoven. Berlioz was perhaps fortunate to die in 1869, a year before the outbreak of war between France and Germany in 1870-1 which ushered in a long period of animosity between the two countries. As a result of the 1870-1 war, Strasbourg and Alsace passed into the German empire, where they remained till the end of the First World War of 1914-1918.

![]()

Unless otherwise specified, the modern photos reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin on 13-14 January 2006, and all other pictures are from our collection.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

|

|

|

This autograph draft is courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The bridge opened in 1861 and linked Strasbourg and Kehl. It was destroyed in the second world war by the retreating French troops on 14 May 1940. (In 1940 a

total of 250 road and railway bridges in Alsace and Lorraine were blown up by dynamite.) ![]()

A new road bridge, the Pont de l’Europe, has replaced this bridge, which was destroyed during the war. The railway bridge is in the background. ![]()

The station started to be built in 1847 and was opened in 1850 as the Embarcadère de Strasbourg; the architect was François-Alexandre Duquesney. It was expanded in 1854 and renamed Gare de l’Est. It was for some time informally referred to as the Gare de Strasbourg.

The railway station at Strasbourg at which Berlioz arrived on 16 June 1863 is no longer extant. The present mainline station dates back to 1878, and thus from the German period. ![]()

The building on the left houses among others a concert hall, the Grande Salle de l’Aubette. On the façade of this building are engraved large medallions, each of which bears the name of a composer: (from left to right) Mendelssohn, Schubert, Rossini, Beethoven, Gluck, Haendel, J S Bach, Mozart, Haydn, C M Weber, Auber, and Schumann. As with the Conservatoire in Paris, Berlioz’s name is conspicuously absent from the square where L’Enfance du Christ was performed in June 1863. ![]()

The Grande Rue is in the old part of Strasbourg which, we were told, has not been reconstructed or changed in any fundamental way. We were unable to find any evidence that the numbering of buildings has changed since

Berlioz’s visit, but this is of course a possibility.

Schwab’s address in Strasbourg was 16 Place au foin, outside the central part of the city (CG no. 2311, in 1858); the building has now disappeared. ![]()

We are most grateful to our friend Pepijn van

Doesburg for sending us this photograph taken by himself in January 2006. ![]()

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Berlioz in Strasbourg page created on 1 March 2006. Revised on 1 September 2023.

© (Unless otherwise specified) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.