![]()

Introduction

Venue and audience

Conductors

Repertoire

Table of performances

Illustrations

This page is also available in French

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.

![]()

Berlioz’s complex and frequently ambivalent relations with the Paris Conservatoire run through almost the whole of his career, and are dealt with elsewhere on this site. The present page aims to present the sequel of the story after Berlioz’s death, by collecting the evidence for performances of Berlioz’s music at the Conservatoire from the time of his death in 1869 till the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The evidence is set out in a chronological table below, which is illustrated with excerpts from announcements and reviews of concerts taken from the weekly journal Le Ménestrel, which are reproduced in the original French. This page thus supplements a series of pages which deal with this same period: the posthumous Berlioz revival in Paris after 1869, and the individual conductors most active in the period covered, Jules Pasdeloup, Édouard Colonne (the most important name of all), and also Charles Lamoureux, together with the successors to the last two named. Taken together all these pages provide a comprehensive if not complete listing of all performances given in Paris from 1869 to 1914 of Berlioz’s orchestral, choral and vocal music. For his stage works (i.e. the 3 operas Benvenuto Cellini, les Troyens, and Béatrice et Bénédict, and staged performances of la Damnation de Faust), see the page on Berlioz’s Operas in France 1869-1914.

Founded in 1828 with François Habeneck as its first conductor, the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire was the oldest concert society in Paris. It differed in several respects from the major concert societies associated with the names of the three conductors just mentioned, the Concerts populaires founded by Jules Pasdeloup in 1861, the Concerts Colonne founded by Édouard Colonne in 1873-4, and the Concerts Lamoureux founded by Charles Lamoureux in 1881. The differences relate to every aspect of the society’s activities: the hall itself, the audience at its concerts, the programmes, the conductors, and indeed the whole culture and outlook of the Conservatoire itself.

While the other concert societies had to perform in venues that were not originally designed for symphonic music (theatres and circus arenas), the Conservatoire enjoyed the unique advantage of having a purpose-built concert hall of its own; it was by common consent the finest in Paris and renowned for its acoustic (see for example the comments of Auguste Morel in 1878 or Julien Tiersot in 1911). The Conservatoire building was actually closed down for a whole season in 1897-1898 when the Library (of which Berlioz had been librarian) was moved to new premises in Rue de Madrid, and concerts were moved temporarily to the less suitable Opéra, but the use of the hall for the regular concerts of the Conservatoire was resumed the following season and continued till the second World War.

Built from 1806-1811, at a time when concert audiences were smaller, the dimensions of the Conservatoire hall were modest: it could only seat just over 1000 people. As a result subscribers to season tickets were eventually divided into two groups, and programmes were repeated in successive weeks to enable each group of subscribers to hear them in turn. But access to the list of subscribers was regarded as something of an expensive privilege, and among the subscribers those of the first series enjoyed a higher status, as they could attend the concerts a week earlier. The Conservatoire concerts thus catered in practice for a restricted section of the Parisian concert-going public; this fact by itself helps to explain the development of the later concert societies which could provide symphonic concerts to much larger audiences: the Pasdeloup concerts could accommodate as many as 5000 listeners, and the Châtelet theatre, the regular venue of the Colonne Concerts had a seating capacity of 3600 (it was a requirement of the Paris council that the Colonne Concerts should always provide a number of seats at reduced prices for the benefit of less affluent concert-goers). It should be mentioned incidentally that in the period covered other concert societies tried to establish themselves from time to time (for example the Concert Cressonnois in 1878, the Concert Sechiari in 1911) though none of them achieved the lasting eminence of the two major ones of Colonne and Lamoureux (Pasdeloup’s Concerts populaires were suspended in 1884, briefly revived in 1886 but came to an end with his death in 1887, and were not resurrected till after the First World War). Given the modest size and exclusive recruitment of the Conservatoire audience its tastes could be expected to be traditional, and its behaviour was generally restrained (see for example Le Ménestrel 30/12/1888, 27/2/1898): there was little of the spontaneous extroversion and even occasional rowdiness that could be seen at the concerts of Pasdeloup and Colonne (Lamoureux’s audience seem to have been comparatively more disciplined, which reflected the conductor’s own preferences).

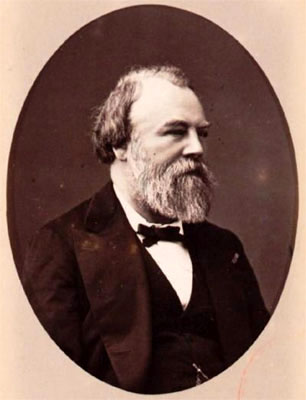

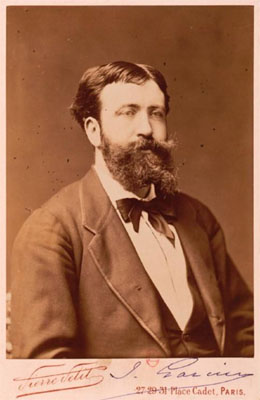

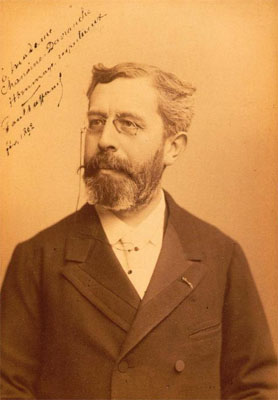

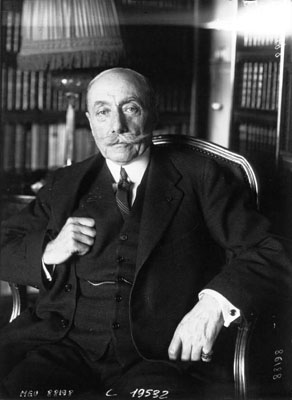

The part played by the conductors at the Conservatoire was also different: whereas the new concert societies were dominated by the personality of the conductors who gave their name to the societies they had founded, the conductors at the Conservatoire were less individually prominent and there was a greater turnover among them. Between 1872 and 1914 there was a succession of no less than five different conductors: Ernest Deldevez (1817-1897) from 1872 to 1884, Jules Garcin (1830-1896) from 1885 to 1892, Paul Taffanel (1844-1908) from 1892 to 1901, Georges Marty (1860-1908) from 1901 to 1908, and André Messager (1853-1929) from 1908 to 1919 (in the table of performances below it can be assumed that unless otherwise indicated all the concerts were conducted by the relevant conductor at the time, for example that from 1872 to 1884 all concerts were conducted by Deldevez). Until André Messager, all the conductors were former students of the Conservatoire; three of them, Deldevez, Garcin and Marty, subsequently became professors there as well, while Taffanel was a distinguished flautist in the Conservatoire orchestra before he became its conductor. Their lesser prominence as conductors may be seen from the fact that reviews of concerts at the Conservatoire frequently do not mention the conductor at all (for one exception, see Le Ménestrel 4/12/1892) but concentrate on the corporate excellence of the orchestral playing (see for example Le Ménestrel 2/4/1899). In general, though first-rate musicians they were less active as guest conductors abroad than was the case with Pasdeloup, Colonne and Lamoureux (and their successors). It was also characteristic of the Conservatoire that it did not invite foreign conductors, and in particular the most celebrated German conductors of the day whose concerts in Paris became in the 1890s and after one of the major attractions of the Colonne and Lamoureux concerts (for example in March 1894 Colonne invited Felix Mottl and Hermann Levi to conduct his orchestra, while Felix Weingartner was invited by Lamoureux in February 1898).

As regards repertoire, the Conservatoire seems to have considered that its function was above all to conserve: in the composition of its programmes it gave precedence to music of the past and well-established classics. These it would perform to a very high standard: the Conservatoire orchestra of the 1830s and 1840s had been widely acknowledged as the finest in Europe, and even after the rise of new orchestral societies which challenged its supremacy, as that of Lamoureux explicitly did, it remained a first rate orchestra, as reviews frequently acknowledged (see for example Le Ménestrel 4/12/1892; 2/2/1896; 27/2/1898; 2/4/1899). But as regards new music from contemporary or near-contemporary composers (such as Wagner and Berlioz, among others, but including also other French contemporary composers), caution was its guiding principle: this is where it was far outdistanced by the Colonne and Lamoureux concert societies.

As regards the music of Berlioz specifically, the Conservatoire, which in the 1830s had given the first performance of several Berlioz’s major symphonic works — notably the Symphonie fantastique, Harold en Italie, and Roméo et Juliette — became later in Berlioz’s career very aloof (for a complete listing of all Berlioz’s concerts in Paris in his lifetime, including at the Conservatoire, see the page Concerts and performances 1825-1869 with its associated page of Texts and documents). In the 1860s the Conservatoire only gave a very limited number of performances: excerpts from part II of la Damnation de Faust (7 April 1861), part II of l’Enfance du Christ (3 & 10 April 1864, 1 April 1866), the duet from Béatrice et Bénédict (22 March, 5 and 8 April 1863; 22 March 1865). It conspicuously failed to commemorate the death of Berlioz, a task which was left to others: no music by him was played before 1872. The table below summarises the performance history of Berlioz at the Conservatoire down to 1914, and the contrast with the programmes of the Pasdeloup concerts, and above all those of Colonne, is very obvious. Generally speaking the Conservatoire played safe and restricted itself to works which had become accepted in the general repertory and would not invite controversy. By far the most frequently played piece was the Carnaval romain overture (43 performances in all). Of the other overtures, les Francs-Juges, le Corsaire and Benvenuto Cellini each received 4 performances, le Roi Lear and Rob-Roy only 2 (the latter work was performed for the centenary celebrations in 1903). With the larger works the tendency of the Conservatoire was to give excerpts rather than complete performances: excerpts, more or less extensive, from Roméo et Juliette were frequently performed (25 times in all), a practice which on one occasion elicited adverse comment from the reviewer who had been expecting the work complete (Le Ménestrel 2/2/1889; in practice the work was performed complete on 8 occasions). Part II of l’Enfance du Christ was an obvious favourite (18 performances), but the complete work was heard only 6 times and late in the day. La Damnation de Faust, much the most popular work of Berlioz in France after the composer’s death and a cornerstone of Colonne’s repertoire (he performed it no less than 157 times), was only played in various excerpts (24 times in all), but never complete. Tristia no. 2 (la Mort d’Ophélie) was popular (13 performances), but no. 3, the imposing funeral march on the death of Hamlet, was only played 3 times, and the complete sequence of 3 movements was never performed. Harold en Italie only received one complete performance (in 1907). A performance of the last movement of the Symphonie funèbre at the Panthéon was projected for the 14th of July celebrations in 1898, but then cancelled. Most striking of all, the Symphonie fantastique, which had been premièred at the Conservatoire in 1830 and which Colonne performed 45 times, was never played in this period: the work may have been felt too provocative for the tastes of the Conservatoire audience. Other absentees from the Conservatoire’s repertory were, understandably, works which required a much larger venue (the Requiem and Te Deum). But no attempt was made to give complete concert performances of any of the operas, such as Pasdeloup and Colonne had occasionally done. Instead the duet from Béatrice et Bénédict was performed from time to time (8 performances), and two scenes from les Troyens were played twice (1899). The songs, including the Nuits d’été, were altogether ignored. Rare performances of other pieces (Sara la baigneuse, the Chant sacré, the Marche troyenne) complete the record.

But it would be misleading to end on a negative note. Among the conductors of the Conservatoire one in particular deserves mention for having made a more distinctive contribution. The appointment of Ernest Deldevez in 1872, replacing George Hainl, brought to the fore a conductor who had the reputation of being well-disposed to Berlioz’s music: he had known the composer and had assisted in the proof-reading of la Damnation de Faust, a work he knew well and admired. During his period as conductor there was a significant increase in performances of Berlioz at the Conservatoire; in particular Deldevez played a role in laying the foundation for the great popularity of la Damnation de Faust by performing excerpts from the work, culminating in two performances of Parts I & II complete in 1876, which no other conductor had done in Paris since the first performances of this work in 1846. He also gave the complete Roméo et Juliette on 4 occasions, in 1880 and 1883 (it was not till the centenary celebrations of 1903 that the work was done again complete). Thanks to Deldevez the Conservatoire thus played a part in the Berlioz revival (cf. Le Ménestrel 18/2/1883). Mention should also be made finally of the last two conductors in this period, Georges Marty and André Messager: to them belongs the credit of having given the first complete performances of l’Enfance du Christ at the Conservatoire, 2 by Marty in 1908, and 4 by Messager in 1909 and 1912.

![]()

The table below has been compiled from concert announcements and reviews in the journal Le Ménestrel which was published in Paris every week throughout this period (initially on Sundays, then from 27 October 1906 on Saturdays), up to the outbreak of the First World War (the last published issue before the war is dated 5 September 1914). The table is self-explanatory; the column on the right gives references to reviews of individual concerts which are reproduced in the original either on other pages of this site (down to March 1884), or on the French version of this page (after this date); it is also used to add occasional notes (e.g. when the conductor was a replacement). Down to 1884 reviews of the Conservatoire concerts were by a number of different critics (and sometimes were not signed). From 1885 to the end of the period covered they became the exclusive preserve of just one critic, Arthur Pougin (1834-1921; photo below), who had close connections with the Conservatoire (he wrote the obituaries for the first four conductors mentioned above); he had joined Le Ménestrel as early as February 1869 and contributed to the paper till not long before his death (on Pougin see further the page on Charles Malherbe). Unlike the Colonne and Lamoureux concerts, where the normal practice of Le Ménestrel was to have two different critics review the same programme in two successive weeks, the Conservatoire concerts were only reviewed once.

The following abbreviations have been used: Béatrice = Béatrice et Bénédict, Carnaval = overture le Carnaval romain, Cellini = Benvenuto Cellini, Corsaire = overture le Corsaire, Damnation = la Damnation de Faust, Enfance = l’Enfance du Christ, Francs-Juges = overture les Francs-Juges, Harold = Harold en Italie, Marche = Marche hongroise from Damnation, Roméo = Roméo et Juliette. Where a title is mentioned without qualification (e.g. Enfance) it refers to a performance of the complete work.

| Date | Work | Le Ménestrel | Reviews/Notes |

| 1869 | |||

| [No performance of Berlioz] | |||

| 1870 | |||

| [No performance of Berlioz] | |||

| 1871 | |||

| [No performance of Berlioz] | |||

| 1872 | |||

| 7 January | Damnation (Part II, excerpts) | 7/1, p. 47; 14/1, p. 55 | Jullien |

| 14 January | Damnation (Part II, excerpts) | 14/1, p. 55 | |

| 3 March | Damnation (excerpt: Chorus of Gnomes and Sylphs) | 3/3, p. 112; 10/3, p. 119 | |

| 13 March | Chant sacré | 17/3, p. 127 | Conducted by Guillot de Sainbris |

| 31 March | Enfance (Part II) | 31/3, p. 144 | |

| 8 December | Damnation (Part II, excerpts) | 15/12, p. 22 | Anon. |

| 15 December | Damnation (Part II, excerpts) | 15/12, p. 22 | |

| 1873 | |||

| 9 March | Carnaval | 16/3, p. 126 | Anon. |

| 6 April | Damnation (aria) | 30/3, p. 141; 6/4, p. 151; 13/4, p. 156 | Planté, piano |

| 23 April | Damnation (aria) | 20/4, p. 167; 28/4, p. 174 | Planté, piano |

| 7 December | Roméo (3rd mov.) | 14/12, p. 14 | Reyer, Anon. |

| 14 December | Roméo (3rd mov.) | 14/12, p. 15 | |

| 1874 | |||

| 1st March | Carnaval | 1/3, p. 103 | |

| 8 March | Carnaval | 8/3, p. 110 | |

| 22 November | Francs-Juges | 22/11, p. 406 | |

| 29 November | Francs-Juges | 29/11, p. 415; 6/12, p. 6 | |

| 27 December | Damnation (Part II, excerpts) | 27/12, p. 30 | |

| 1875 | |||

| 3 January | Damnation (Part II, excerpts) | 10/1, p. 47 | Anon., Reyer |

| 31 January | Tristia no. 2 | 31/1, p. 71 | |

| 7 February | Tristia no. 2 | 7/2, p. 79 | |

| 5 December | Carnaval | 5/12, p. 6; 12/12, p. 15 | |

| 12 December | Carnaval | 12/12, p. 15 | |

| 1876 | |||

| 13 February | Damnation Parts I & II | 6/2, p. 78; 13/2, p. 87; 20/2, p. 94 | Wilder, Reyer |

| 20 February | Damnation Parts I & II | 20/2, p. 95 | |

| 31 December | Roméo (3e mouv.) | 31/12, p. 39 | |

| 1877 | |||

| 7 January | Roméo (3rd mov.) | 7/1, p. 36 | Conducted by Charles Lamoureux |

| 1878 | |||

| 10 February | Roméo (2nd & 3rd mov.) | 10/2, p. 87 | Conducted by Ernest Altès |

| 17 February | Roméo (2nd & 3rd mov.) | 17/2, p. 95 | Conducted by Ernest Altès |

| 17 March | Tristia no. 2 | 17/3, p. 128; 24/3, p. 134 | |

| 24 March | Tristia no. 2 | 24/3, p. 136 | |

| 31 March | Carnaval | 31/3, p. 142 | |

| 7 April | Carnaval | 7/4, p. 150 | |

| 28 April | Harold (2nd mov.) | 21/4, p. 165; 5/5, p. 179 | Concert by students of the Conservatoire |

| 1st December | Carnaval | 1/12, p. 7; 8/12, p. 16 | Morel |

| 8 December | Carnaval | 8/12, p. 16 | |

| 1879 | |||

| 5 January | Roméo (excerpts) | 5/1, p. 47; 12/1, p. 56 | Wilder, Reyer |

| 12 January | Roméo (excerpts) | 12/1, p. 56 | |

| 30 November | Carnaval | 30/11, p. 420 | |

| 7 December | Carnaval | 30/11, p. 420 | |

| 1880 | |||

| 4 January | Tristia no. 2 | 4/1, p. 39 | Conducted by Ernest Altès |

| 11 January | Tristia no. 2 | 11/1, p. 47 | Conducted by Ernest Altès |

| 8 February | Roméo | 8/2, p. 79 | |

| 15 February | Roméo | 15/2, p. 86; 22/2, p. 94 | |

| 5 December | Corsaire | 5/12, p. 6; 12/12, p. 14 | Wilder |

| 12 December | Corsaire | 12/12, p. 14 | |

| 1881 | |||

| 9 January | Carnaval | 9/1, p. 46 | |

| 16 January | Carnaval | 16/1, p. 55 | |

| 27 February | Roméo (excerpts) | 27/2, p. 104 | |

| 6 March | Roméo (excerpts) | 6/3, p. 112; 13/3, p. 119 | Wilder; conducted by Ernest Altès |

| 1882 | |||

| 22 January | Damnation (excerpts) | 22/1, p. 64 | |

| 29 January | Damnation (excerpts) | 29/1, p. 71; 5/2, p. 78 | |

| 19 November | Carnaval | 19/11, p. 407; 26/11, p. 415 | |

| 26 November | Carnaval | 26/11, p. 415 & 416 | |

| 1883 | |||

| 28 January | Roméo | 28/1, p. 72; 4/2, p. 79 | |

| 4 February | Roméo | 4/2, p. 80 | |

| 23 March | Enfance (Part II) | 18/3, p. 127 | Good Friday |

| 24 March | Enfance (Part II) | 18/3, p. 127; 25/3, p. 134 | Anon. |

| 1884 | |||

| 10 February | Tristia no. 2 | 10/2, p. 88; 17/2, p. 95 | |

| 17 February | Tristia no. 2 | 17/2, p. 96 | |

| 16 March | Roméo (excerpts) | 16/3, p. 128; 23/3, p. 135 | Anon. |

| 23 March | Roméo (excerpts) | 23/3, p. 136 | |

| 7 December | Francs-Juges | 7/12, p. 8; 14/12, p. 14 | |

| 14 December | Francs-Juges | 14/12, p. 14 | |

| 1885 | |||

| 8 February | Carnaval | 8/2, p. 80 | |

| 15 February | Carnaval | 15/2, p. 88 | |

| 22 March | Enfance (Part II) | 22/3, p. 128; 29/3, p. 134 | Pougin |

| 29 March | Enfance (Part II) | 29/3, p. 136 | |

| 1886 | |||

| 17 January | Enfance (Part II) | 17/1, p. 56 | |

| 24 January | Enfance (Part II) | 24/1, p. 63 | |

| 21 February | Carnaval | 21/2, p. 95; 28/2, p. 104 | Pougin |

| 1887 | |||

| 27 February | Carnaval | 27/2, p. 102; 6/3, p. 110 | |

| 6 March | Carnaval | 6/3, p. 111 | |

| 1888 | |||

| 23 December | Enfance (Part II) | 23/12, p. 415; 30/12, p. 419-20 | Pougin |

| 30 December | Enfance (Part II) | 30/12, p. 420 | |

| 1889 | |||

| 27 January | Roméo (with cuts) | 27/1, p. 31; 3/2, p. 39 | Pougin |

| 3 February | Roméo (with cuts) | 3/2, p. 39 | |

| 2 March | Marche troyenne | 24/2, p. 62 | Performed by the Musique de la Garde républicaine |

| 8 December | Carnaval | 8/12, p. 390; 15/12, p. 397 | |

| 15 December | Carnaval | 15/12, p. 397 | |

| 1890 | |||

| 2 March | Béatrice (duet) | 2/3, p. 70 | |

| 9 March | Béatrice (duet) | 9/3, p. 77 | |

| 1891 | |||

| 8 March | Carnaval | 8/3, p. 77; 15/3, p. 85 | |

| 15 March | Carnaval | 15/3, p. 86 | |

| 19 April | Enfance (Part II) | 19/4, p. 127; 26/4, p. 133 | |

| 26 April | Enfance (Part II) | 26/4, p. 134 | |

| 6 December | Béatrice (duet) | 6/12, p. 391; 13/12, p. 397 | |

| 13 December | Béatrice (duet) | 13/12, p. 397 | |

| 20 December | Damnation (excerpts) | 20/12, p. 405; 27/12, p. 412 | Pougin |

| 27 December | Damnation (excerpts) | 27/12, p. 413 | |

| 1892 | |||

| 10 January | Harold (2nd mov.) | 17/1, p. 20 | Conducted by Danbé |

| 17 January | Harold (2nd mov.) | 17/1, p. 21 | |

| 11 December | Roméo (excerpts) | 11/12, p. 397; 18/12, p. 405 | Pougin |

| 18 December | Roméo (excerpts) | 18/12, p. 406 | |

| 1893 | |||

| 10 December | Enfance (Part II) | 10/12, p. 396; 17/12, p. 404 | Pougin |

| 17 December | Enfance (Part II) | 17/12, p. 405 | |

| 24 December | Carnaval | 24/12, p. 413; 31/12, p. 419 | |

| 31 December | Carnaval | 31/12, p. 419 | |

| 1894 | |||

| [No performance of Berlioz] | |||

| 1895 | |||

| 31 March | Cellini (overture) | 31/3, p. 101; 7/4, p. 109 | |

| 7 April | Cellini (overture) | 7/4, p. 109 | |

| 1896 | |||

| 26 January | Roméo (excerpts) | 26/1, p. 30; 2/2, p. 38 | Pougin |

| 22 March | Carnaval | 22/3, p. 92; 29/3, p. 100 | |

| 29 March | Carnaval | 29/3, p. 101 | |

| 3 April | Enfance (Part II) | 5/4, p. 109 | Good Friday |

| 13 December | Cellini (overture) | 13/12, p. 397; 20/12, p. 404 | |

| 20 December | Cellini (overture) | 20/12, p. 404 | |

| 1897 | |||

| 3 January | Marche | 3/1, p. 6; 10/1, p. 13 | |

| 10 January | Marche | 10/1, p. 13 | |

| 12 December | Béatrice (duet) | 12/12, p. 396; 19/12, p. 404 | Concert at the Opéra |

| 19 December | Béatrice (duet) | 19/12, p. 404 | |

| 1898 | |||

| 20 February | Roméo (excerpts) | 20/2, p. 61; 27/2, p. 68 | Pougin |

| 27 February | Roméo (excerpts) | 27/2, p. 68 | |

| 17 April | Carnaval | 17/4, p. 124 | |

| [14 July] | [Symphonie funèbre (Apothéose)] | 10/7, p. 222; 17/7, p. 226-7 | Tiersot (Panthéon; not performed) |

| 1899 | |||

| 8 January | Le Roi Lear | 8/1, p. 14; 15/1, p. 20 | Concert at the Conservatoire |

| 15 January | Le Roi Lear | 15/1, p. 21 | |

| 5 February | Tristia nos. 2 & 3 | 5/2, p. 46; 12/2, p. 53 | Pougin |

| 12 February | Tristia nos. 2 & 3 | 12/2, p. 54 | Jullien |

| 26 March | La Prise de Troie (scenes 2 & 3) | 26/3, p. 101; 2/4, p. 109 | Pougin |

| 9 April | La Prise de Troie (scenes 2 & 3) | 9/4, p. 116 | Jullien |

| 17 December | Marche hongroise | 17/12, p. 404; 24/12, p. 412 | |

| 24 December | Marche hongroise | 24/12, p. 412 | |

| 1900 | |||

| 7 January | Carnaval | 7/1, p. 4; 14/1, p. 13 | |

| 14 January | Carnaval | 14/1, p. 13 | |

| 21 January | Enfance (Part II) | 28/1, p. 28 | Pougin |

| 28 January | Enfance (Part II) | 28/1, p. 29 | |

| 4 February | Roméo (excerpts) | 4/2, p. 37; 11/2, p. 46 | |

| 11 February | Roméo (excerpts) | 11/2, p. 46 | |

| 31 May | Roméo (Part II) | 27/5, p. 167 | Trocadéro; first concert of the Exhibition |

| 1901 | |||

| 10 February | Cellini (overture) | 10/2, p. 45; 17/2, p. 52 | |

| 17 February | Cellini (overture) | 17/2, p. 53 | |

| 29 December | Corsaire | 29/12, p. 412; 5/1/1902, p. 5 | |

| 1902 | |||

| 5 January | Corsaire | 5/1, p. 6 | |

| 7 December | Damnation (chorus of soldiers & students) | 7/12, p. 389; 14/12, p. 396 | |

| 14 December | Damnation (chorus of soldiers & students) | 14/12, p. 396 | |

| 1903 | |||

| 1 February | Carnaval | 1/2, p. 38; 8/2, p. 45 | |

| 8 February | Carnaval | 8/2, p. 45 | |

| 22 March | Sara la baigneuse | 22/3, p. 93; 29/3, p. 100-1 | Pougin |

| 29 March | Sara la baigneuse | 29/3, p. 101 | |

| 6 December | Rob Roy, Roméo | 6/12, p. 389; 13/12, p. 396 | Pougin |

| 13 December | Rob Roy, Roméo | 13/12, p. 396 | |

| 1904 | |||

| 5 May | Tristia nos. 2 & 3 | 1/5, p. 143; 8/5, p. 150 | Pougin |

| 1905 | |||

| 5 February | Carnaval | 5/2, p. 45; 12/2, p. 52 | |

| 12 February | Carnaval | 12/2, p. 53 | |

| 26 March | Tristia no. 2 | 26/3, p. 100; 2/4, p. 109 | |

| 2 April | Tristia no. 2 | 2/4, p. 109 | |

| 21 April | Damnation (Part II, excerpts) | 23/4, p. 133 | Good Friday |

| 1906 | |||

| 11 February | Enfance (Part II) | 11/2, p. 45; 18/2, p. 53 | |

| 18 February | Enfance (Part II) | 18/2, p. 53 | |

| 1907 | |||

| 10 March | Harold | 9/3, p. 76 | First performance at the Conservatoire since 1843; no published review |

| 14 April | Béatrice (duet) | 13/4, p. 119 | |

| 21 April | Béatrice (duet) | 20/4, p. 127 | |

| 1908 | |||

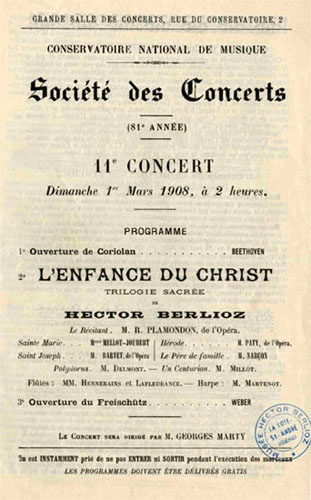

| 1st March | Enfance | 29/2, p. 68 | First complete performance at the Conservatoire; see the programme below |

| 8 March | Enfance | 7/3, p. 76 | Jullien |

| 1909 | |||

| 14 February | Roméo | 13/2, p. 52; 20/2, p. 60 | Pougin |

| 21 February | Roméo | 20/2, p. 61 | |

| 19 December | Enfance | 18/12, p. 404; 25/12, p. 412 | Pougin |

| 26 December | Enfance | 25/12, p. 412 | Jullien |

| 1910 | |||

| 23 January | Carnaval | 22/1, p. 29 | |

| 30 January | Carnaval | 29/1, p. 36; 5/2, p. 45 | |

| 1911 | |||

| 26 February | Carnaval | 25/2, p. 62; 4/3, p. 68 | |

| 5 March | Carnaval | 4/3, p. 69 | |

| 1912 | |||

| 28 January | Roméo (Parts IV & II) | 27/1, p. 28; 3/2, p. 37 | |

| 4 February | Roméo (Parts IV & II) | 3/2, p. 37 | |

| 24 November | Carnaval | 23/11, p. 373; 30/11, p. 380 | |

| 1st December | Carnaval | 30/11, p. 380 | |

| 22 December | Enfance | 21/12, p. 405; 28/12, p. 412 | Pougin |

| 29 December | Enfance | 28/12, p. 413 | |

| 1913 | |||

| [No performance of Berlioz] | |||

| 1914 | |||

| 1st March | Carnaval | 28/2, p. 68; 7/3, p. 76 | |

![]()

All the pictures in this section are courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

The following picture is courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

On Pougin see further the page on Charles Malherbe, and his obituary notice.

The original copy of the following programme is in the Hector Berlioz Museum, which possesses a large collection of concert programmes. We are most grateful to the Museum for granting us permission to reproduce its scanned copy on this page. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir

Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Page Berlioz: Pioneers and

Champions created on 15 March 2012; this page created on 1 May 2013.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.