By

© 2004 Pierre-René Serna

Translated by Michel Austin

© Michel Austin

This page is also available in French

The hall of the former Conservatoire1 (nowadays the Conservatoire d’Art Dramatique, in Paris’ 9th arrondissement), still remains that well-kept secret, unknown to tourists and to many Parisians. Yet this building, loaded with an illustrious musical past that is without equal, provides a unique testimony on the art of the concert halls of the past and is a priceless architectural jewel.

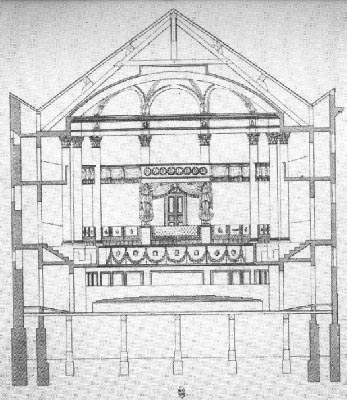

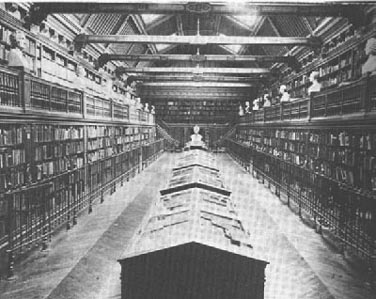

Originally, that is in the early XVIIth century, the area of the Faubourg Poissonnière was nothing but open fields and wasteland beneath the ramparts surrounding Paris. When these were demolished and the Boulevards created, the area beyond the old city limits was parcelled out for residential homes and private hotels. This extended area of Paris, henceforth called La Nouvelle France2, attracted royal attention and in the brand new rue Bergère it was decided to set up the Hôtel des Menus Plaisirs. This institution, the equivalent of the present Ministry of Culture, included within its precinct art schools and companies of actors and musicians. The architect Louis-Alexandre Giraud, who collaborated with Gabriel on the Opéra of the Versailles Château, was responsible for the original building, built between 1763 and 1787; it included storage rooms for stage sets and workshops, to which were added an adjoining theatre. This theatre, the former Théâtre de la Foire Saint-Laurent of 1752, the work of the famous stage engineer Arnould, was dismantled then reassembled at the Menus Plaisirs; it witnessed among others the first performance of La Serva Padrona by Pergolese. It was on this spot that at the instigation of Napoleon I the present hall was built between 1806 and 1811, on the plans of the architect Delannoy, inspired by the original model. Other buildings were added later, such as the library in 1808. In the meantime (in 1795), to take the place of the menus plaisirs, too redolent of the Ancien Regime, the Conservatoire of music and declamation was instituted.

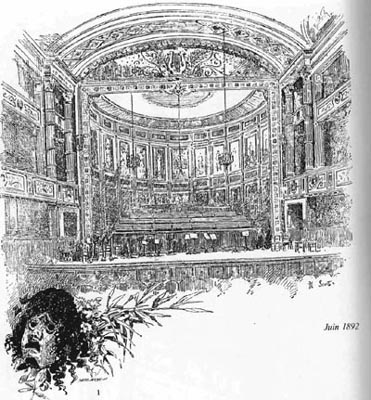

From then on, this hall, one of the very first concert halls in history, became the musical meeting-place of Europe. The Concerts Français founded by Habeneck were succeeded in 1828 by the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, presided over by Cherubini; its inaugural concert took place on 9 March. This was the setting for the first performances in France of Beethoven’s symphonies and the majority of Berlioz’s symphonic works3. Its incomparable acoustic was hailed from its opening and celebrated by musicians all over the world, and it long remained a model. Concerts were given there regularly up to the Second World War, infrequently thereafter (notably by the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire until 1967, at which date it was dissolved and integrated in the Orchestre de Paris). They ceased thereafter, for reasons partly of safety (the building is of timber), and partly of profitability (the capacity of the hall is limited), but also because in the meantime the teaching of music had been removed to another place. The paradoxical result was that a concert hall was bequeathed for the exclusive use of students of dramatic art.

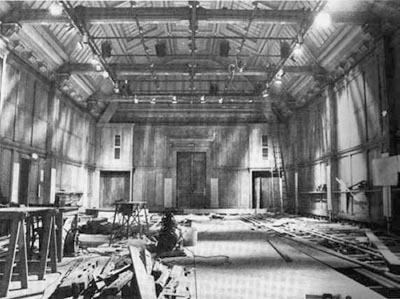

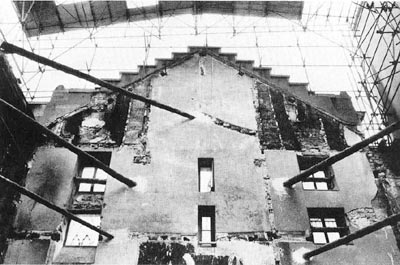

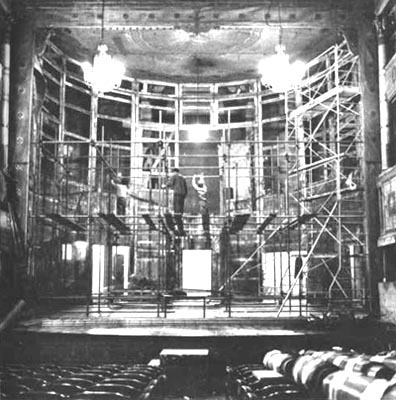

It was at this juncture that the building, which had as it were remained outside time and had hardly changed since it was built (except for the decoration, which was renewed in 1866), underwent in 1985 extensive restoration and reconstruction. The shell of the hall itself was preserved, but the stage was completely rebuilt, from the foundations to the roofing. The frame of the stage was raised, and the original timberwork was replaced by a concrete load-bearing structure, with a metal framework and arches, and the stage support was completely renovated with modern materials. Similarly the set for concerts, which previously was permanently fixed, was changed into a movable set, similar but resting on aluminium tighteners. As for the proscenium it was discarded, which restricted the surface of the stage. In the hall itself, broad velvet armchairs reduced the seating capacity and the arrangement of the seats was itself modified (only one block of stalls instead of two separated by a passage), and the floor was covered with a fitted carpet. In carrying out these adjustments, which the age of the building certainly made imperative, the Monuments Historiques (this is a listed building) seems to have favoured the decoration (which has been wonderfully restored), but at the expense of the building’s intrinsic character.

One may therefore raise a number of questions. The materials used (concrete and metal for the stage, velvet and a fitted carpet for the hall) run counter to current acoustic criteria, at the very time4 when concert halls – the Châtelet, Pleyel, Bastille – are reintroducing timber. The same applies to the increased height of the stage’s frame. In addition the reduction in the space on the stage makes large-scale symphonic concerts a virtual impossibility, particularly in the presence of the set designed for this purpose. It is thus rather unlikely that in present conditions Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette, a symphony with chorus and solo singers, can ever be performed in the very hall where it was first heard.

The capacity of the hall has constantly declined, from about one thousand places (originally 1,078 to be precise, taking into account the gallery, which subsequently was not used) to about 450 at present. This makes even more illusory any intention of programming genuine symphonic concerts in a hall originally designed for this very purpose. All this is even more difficult to explain as a renovation carried out with regard to acoustics and the original capacity of the hall could only have benefited its use as a theatre… What would have been the reaction if the Versailles Opéra (of which the Conservatoire is a direct heir, as seen above) had been treated in a similar way? One might be led to suspect a wilful attempt to erase every vestige of a glorious past and preclude any possibility of ever bringing it back.

Pierre-René Serna

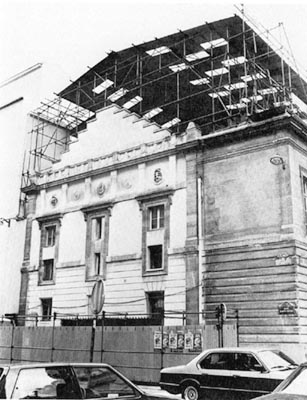

The front part of the building was demolished in the 1930s and now houses a post office building.![]()

The entire frame of the stage was demolished, except for the sides which are visible from the street.![]()

The original ceiling of the set for concerts is clearly visible; it enclosed the stage before it was dismantled.![]()

Photo taken by Michel Austin in November 2000.![]()

____________________________

Notes

* This article was originally published in October 1991 in

the journal Mélomane; here it has been partly modified.![]()

1. The Conservatoire national de musique et de déclamation was first moved in 1911 to the rue de Madrid; it was then split into two distinct entities from 1949 (dramatic art was moved back to the original building), and the musical section was transferred in 1990 to the Cité de la Musique at la Villette.![]()

2. Not to be confused with La Nouvelle Athènes, in the western part of the present 9th arrondissement, where Berlioz selected his flats from 1834 onwards, and where he settled from 1836 to his death.![]()

3. The Symphonie fantastique, Lélio (called at

the time le Retour à la vie), Harold and Roméo.![]()

4. The reader is reminded that the article was written in

1991.![]()

![]()

We are most grateful to our friend Pierre-René Serna for sending us this article. M. Serna, a distinguished music critic, has co-edited [with Christian Wasselin] Berlioz (L’Herne, Paris, 2003) and is the author of Berlioz de B à Z (Éditions Van de Velde, 2006). Many thanks also to our friend Olivier Teitgen for the photos and illustrations. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 10 December 2004, enlarged in February 2005.

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin.

![]() Back to Paris Conservatoire main page

Back to Paris Conservatoire main page

![]() Back to Berlioz in Paris page

Back to Berlioz in Paris page