![]()

This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz’s trip to Naples and Campania in October 1831 was one of the highlights of his stay in Italy; it is illustrated by the letters he wrote at the time to his family and to friends (CG nos. 244, 246, 247, 248, 258), and by two chapters in the Memoirs (40-41), though the letters provide numerous details that are missing in the Memoirs. Yet the trip came about by accident, and was not Berlioz’s own idea (he was short of money ever since his expedition to Nice in April and May). The account in the Memoirs makes this clear (end of chapter 40):

[…] I was sleeping one day in the laurel grove in the gardens of the Academy, rolled up like a hedgehog in a heap of dead leaves, when I felt prodded by the feet of two of my companions: Constant Dufeu, the architect and Dantan the elder, the sculptor, who had come to wake me up.

— Hey there, Father Grumpy! Do you want to come to Naples? We are heading there.

— Get lost! You know I have no money left.

— You fool! We have money and will lend you some!

Come on, Dantan, give me a hand, pick him up otherwise we won’t get anything out of him. Good, so you are on your feet!... Shake yourself, and go and ask M. Vernet leave for a month, and as soon as your suitcase is ready, we are off, that’s a deal.

And so we set out. […]

The sculptor Dantan made a medallion of Berlioz in Rome in 1831.

The trip was different in character from all the excursions that Berlioz had been making earlier in the summer around Subiaco and the Abruzzi mountains on his own and on foot, carrying a gun and his guitar. This time he journeyed ‘like a bourgeois travelling by coach’ as he admits in the same chapter of the Memoirs, with a few companions, with neither gun nor guitar, and for the purpose of sight-seeing like any tourist of the time.

Berlioz’s letters (especially CG nos. 244 and 246) make it possible to establish a fairly exact chronology of his trip, which is missing in the account of the Memoirs. Berlioz will have left Rome at the end of September, since he arrived in Naples on 1 October. On 2 October he visited Posilippo and ‘Virgil’s Tomb’, and between 3 and 5 October he made an excursion on foot with several companions to Mt Vesuvius. On 6 October he stayed in Naples; the next day he made on his own an excursion to the island of Nisida and in the evening admired the sunset from Mount Posilippo. On 8 October he stayed in Naples. Between 9 and 12 October he visited Pompeii with four other companions, then Castellamare, and returned by foot on his own to Naples. He finally left Naples for Rome on 14 October.

Berlioz’s first impressions of Naples were positive as compared with Rome (CG no. 244, 2 October, to his family):

[…] Nothing can obliterate or even equal this gulf that stretches out in front of me, this smoking Vesuvius, this sea covered with boats […] these colourful crowds bustling about in the streets […] What life!… What movement! What dazzling activity! How different this is from Rome, its sleepy inhabitants, its naked soil, bare, barren and deserted! The fields around Rome are to the plains of Naples like the past to the present, like death to life, like silence to a harmonious and brilliant burst of sound. […]

Looking back years later Berlioz’s memories were similar (Memoirs chapter 41):

Naples! The pure and clear air, the drenching sun, the fertile earth!

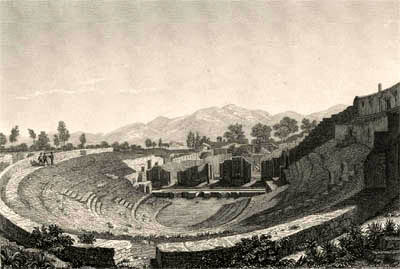

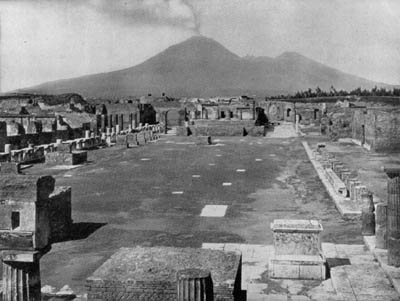

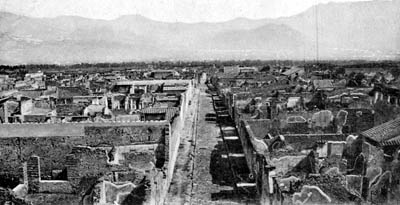

Everyone has described, much better than I can, this wonderful garden. No traveller has failed to be struck by the splendour of the sight. Everyone has admired the sea resting at noon, its soft blue folds, and the soothing ripple of the waves. Anyone stranded at dead of night in the crater of Vesuvius will have experienced a strange feeling of awe at the rumble of subterranean thunder, or the fury that belches from its mouth, at the explosions, the quantities of molten rock hurled at heaven like incandescent cries of blasphemy, which fall back to the ground, roll over the side of the mountain and come to a halt forming a fiery necklace on the vast neck of the volcano! Who has not wandered sadly through the skeletal desolation of Pompeii, a solitary spectator expecting from the terraces of the amphitheatre the performance of a tragedy by Euripides or Sophocles for which the stage still seems to be set? Who has not warmed up to the habits of the lazzaroni, this enchanting population of children, with their exuberance, their addiction to stealing, their mocking wit, and their occasional moments of genuine goodness? […]

A letter to his family describes in more detail the visit to Pompei (CG no. 246, 17-21 October):

[…] Since my last letter, I have visited the famous ruins of Pompeii; I do not want to bore you with a description of this skeleton of a city, but without doubt it corresponds to expectations. But my four travelling companions and the guide spoiled my little ancient world; that is not the effect that Pompeii has. I was cursing inwardly the circumstances which prevented me from being on my own, wandering at night among the columns and their shadows, seen only by the moon and free to surrender to all my impressionable impulses, not to say my imagination. It must be wonderful to be able to dream thus surrounded by silence, walking on these large smooth slabs, in these long echoing streets, among the temples and palaces; to go and sit in the great tragic theatre, thinking of Sophocles and Euripides; to thrill in the immense amphitheatre, gazing through the mists of time at the gladiators, lions and tigers, and, more frightening still, the people thirsting for blood, watching avidly the heart of the victim being torn apart by the claws of a desperate animal, and cheering as it throbs for the last time. I would have loved to sleep in one of those charming houses paved with mosaics, which imagination fills with beautiful women draped in Greek style with an imperious look on their face, and surrounded by beautiful slave girls playing the lyre and singing of pleasure. But all this is impossible. There are guards everywhere who follow you with a watchful eye; I have not even been able to steal for my father a miserable fragment from a fresco or a mosaic. […]

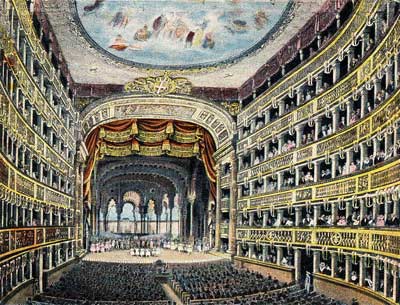

While in Naples, Berlioz attended a concert at the vast San Carlo Theatre, as he relates in the Memoirs (Chapter 41):

[…] At the San Carlo Theatre … I heard, for the first time since my arrival in Italy, genuine music. The orchestra seemed to me excellent compared with those I had seen up till then. The wind instruments can be listened to without discomfort, and there is nothing to fear from them; the violins are fairly capable, and the cellos have a good singing style, though there are too few of them. The system, widespread in Italy, of always having fewer cellos than double-basses, cannot even be justified by the kind of music that Italian orchestras normally perform. I would also criticise the maestro di capella for the highly disagreeable noise of his bow striking his desk rather roughly; but I have been assured that without that, the musicians he conducts would sometimes be hard-pressed to follow the beat… That is an unanswerable argument; after all, in a country where instrumental music is virtually unknown, you cannot expect orchestras such as those of Berlin, Dresden or Paris. The choristers are extremely weak; I have it from a composer who has written for the San Carlo theatre [probably Julius Benedict], that it is very difficult if not altogether impossible to obtain a satisfactory execution of choruses written for four parts. The sopranos have great difficulty in moving independently of the tenors, and you are so to speak obliged to make them constantly double the tenor part an octave above.

As far as music-making was concerned Berlioz found Naples superior to Rome, though as he put it ‘the musical attractions of the theatres in Naples could not compete on equal terms with those provided by the exploration of the countryside around the city’ (Memoirs, chapter 41). But on 8 October while visiting the museum where ancient instruments from the ruins of Herculanum where exhibited, he tried out two pairs of ‘antique cymbals’ which he later used in the Queen Mab scherzo in Romeo and Juliet and in one of the ballets of The Trojans (CG no. 244).

Berlioz would have like to pursue further his explorations around Naples, but lack of money forced him to curtail his visit: he was unable to see Paestum, Salerno and Amalfi (CG no. 244), and he had to give up the idea of going to Sicily (CG nos. 246, 269). But Berlioz made a virtue of necessity (CG no. 246, 17-21 October, to his family):

I left Naples last Friday [14 October] on foot with two Swedish officers who speak very good French and are excellent company. This way of travelling through the country is incomparably more pleasant than the ordinary method, particularly at this time; the sun is no longer overpowering, the Sirocco has stopped blowing, fruits are ripe, the grapes are being gathered everywhere, and there is a delicious breeze; it is the pleasant season of Italy. […] There has not been any other drawback apart from fatigue and arguments over stolen pears, grapes or figs when the owners were not there to sell them to us. This life of wandering is very enjoyable; my personal effects are with the postal service which is taking them to Rome. All I have is my wallet, my walking stick, and my purse, and I cannot complain about the weight of the latter. Besides it is diminishing as I get tired and will end by disappearing completely by the time I arrive. […]

The Swedish officers were named Mauritz Klingsporn and Carl Stephan Bennet; the latter kept a diary of the journey from Naples in the company of Berlioz which is extant. The return journey took a week and brought them via San Germano, Isola di Sora, Alatri, and Arcino finally to Subiaco. After staying three days there they proceeded to Tivoli and finally to Rome (CG no. 247). Berlioz was delighted with the excursion, as he wrote to his friend Thomas Gounet a few weeks later (CG no. 248, 28 November):

[…] Last month I came back from Naples on foot, across mountains, woods, rocks, and high pasture-lands, and only once did I need the services of a guide. You cannot imagine the attractions of such a journey: the fatigue, hardship, and apparent risk involved, I found all delightful. It took me nine days which I shall long remember. […]

![]()

Unless otherwise stated, all the pictures reproduced on this page have been scanned from engravings, newspapers, postcards and old photos in our collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

The original copy of the engravings on this page have been donated by us to the Hector Berlioz Museum and they hold copyright for them.

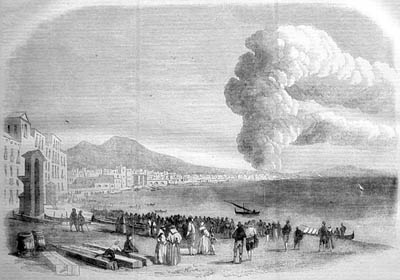

This event was reported in the Illustrated London News, on 11 December 1843.

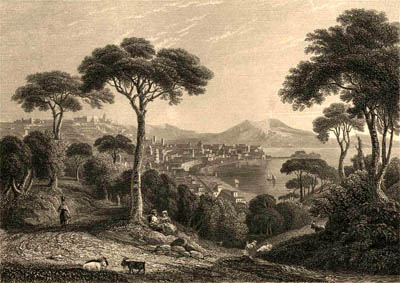

This steel engraving, entitled ‘Early Morning’ and drawn in the 1870s by R Wallis, is based on an earlier drawing by the British artist William Callow (1812-1908).

The above postcard reproduces a painting by Camille Corot entitled ‘Vue près de Naples’.

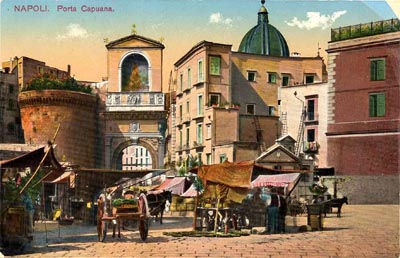

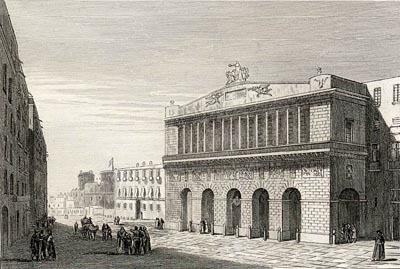

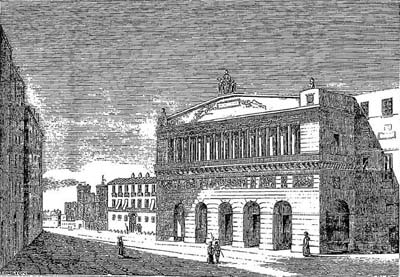

The above engraving was published in 1837 in Le Magasin Pittoresque, page 229. An electronic copy of the magazine is available on the internet site of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

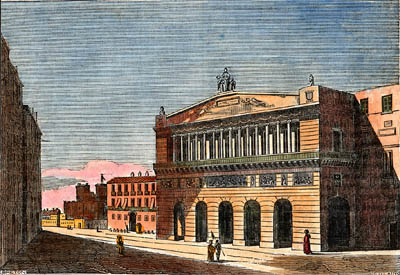

This is the same engraving on the same page taken from a print copy of the magazine, hand-painted by one of its previous owners some time later (it is now in our collection). The thickness of the paint is felt when it is touched.

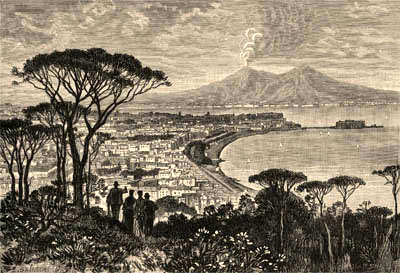

The above engraving was published in L’Italia Geografica Illustrata, 1891, page 221.

![]()

© Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.