![]()

Introduction

Berlioz and Hiller

The visit to Cologne

Cologne: buildings and venues

This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz gave only one concert in Cologne (Köln), in February 1867, near the end of his active career. But it can be inferred from his correspondence that he had in fact stayed in Cologne (at the Hôtel Royal) on more than one occasion before (cf. Correspondance générale no. 3212, January 1867; hereafter CG for short). One definite instance was in late June 1847, on his way back from Russia and Berlin (CG no. 1115). Berlioz may also have visited Cologne at other times. In August 1845, when attending the Beethoven celebrations in Bonn he was asked by the newly founded paper Le Monde to report in detail on the musical celebrations held in Bonn and neighbouring cities – Cologne, Brühl, Stoltzenfelds and Coblenz – though it is not clear whether he actually stayed in them on this occasion (CG no. 992). He stopped at Cologne in April or May 1846 at the end of his second trip to Germany (cf. CG no. 1044bis [in vol. VIII]), and again in November 1852 (cf. CG no. 1530bis [in vol. VIII]), and may have done so at other times in the course of his travels to and from Germany during the years 1853-1856, though specific evidence appears to be lacking. But for many years Berlioz evidently did not judge Cologne to be sufficiently promising ground for attempting a concert there, unlike many other German cities he visited.

The visit to Cologne in February 1867 was prompted by a suggestion from his old friend the composer, pianist and conductor Ferdinand Hiller (1811-1885). Hiller had been appointed Kapellmeister in Cologne as far back as 1850, a post he held till 1884, shortly before his death, and soon after his appointment he had sounded out Berlioz on the possibility of his coming to conduct his music there, though this was not followed up at the time (CG no. 1344, 26 September 1850; cf. 1355, 3 November). Hiller says that he had long wanted to invite Berlioz to Cologne to perform one of his works there, but it was only in 1866 that another invitation from Hiller was taken up by Berlioz: the background to this needs first to be sketched out in order to place the visit in a wider context.

![]()

The relations between the two men had a long history stretching back to their student days in Paris in the late 1820s, as is known from their own writings – Berlioz’s correspondence and Memoirs, and the volume of reminiscences which Hiller published in 1880 (Künstlerleben, [‘Lives of Artists’], 309 pages; pp. 63-143 are devoted to his relations with Berlioz). Hiller’s testimony betrays familiarity with Berlioz’s own Memoirs which had been published in 1870 and supplements them; excerpts from Hiller’s writings will be found in Michael Rose, Berlioz Remembered (London, 2001; see the index p. 308 s.v. Hiller, and see also below).

Hiller had first come to Paris in 1828 where he met Berlioz; their friendship had a number of side-effects, both musical and personal. Hiller helped to introduce Berlioz to Beethoven’s piano music (CG nos. 117, 138, 148) and gave the first performance of the Emperor concerto in Paris at a concert at the Conservatoire on 1 November 1829 where Habeneck also conducted several works of Berlioz (CG no. 141). Hiller also inadvertently introduced Berlioz to Camille Moke. As Berlioz related later in the Memoirs (chapter 28):

A young lady, the best known of present-day virtuosos for her talent and adventures [Camille Moke], had aroused a veritable passion in the German pianist and conductor H*** [Ferdinand Hiller], whose close friend I had become as soon as he arrived in Paris. H*** knew of my Shakespearean love and felt sorry for the torment I was enduring because of it. With unguarded naivety he would often talk about it to Miss M*** and told her he had never seen anyone as madly in love as I was. ‘I could never feel any jealousy for that man, he added one day, I am positive he will never fall in love with you!’ You can imagine the effect of this thoughtless confession on such a Parisian lady. Her fondest dream was to prove wrong her all too trusting and Platonic admirer.

The inevitable happened – Berlioz and Camille met and fell in love with each other; Berlioz concludes:

Poor H***, to whom I felt I had to confess the truth, shed at first some bitter tears, but then realising that deep down I had not been guilty of any treachery towards him he accepted his fate with dignity and courage, clasped my hand convulsively and departed for Frankfurt, wishing me every success. I have always admired his behaviour on this occasion.

Hiller stayed in fact several more years in Paris, till 1835, and Berlioz wrote to him frequently during his stay in Italy in 1831 and 1832 (CG nos. 203, 206, 207, 223, 241, 250, 256, 265, 270, 284). In his account of the first performance of the Symphonie fantastique on 5 December 1830 in the Memoirs (chapter 31) Berlioz comments on the different reception given by the public to the various movements of the symphony, and relates:

The Scene in the countryside [the third movement] made no impact on the public. Admittedly it was at the time very different from what it now is. I decided there and then to rewrite the movement, and F. Hiller, who at the time was in Paris, gave me excellent advice on the subject which I tried to put to good use.

During his stay in Paris in the early 1830s Hiller participated in a number of concerts of chamber and orchestral music, which included performances of the two symphonies he had written at that time. Berlioz reviewed a number of these concerts in the years 1833-1835 (Critique Musicale I pp. 119-20, 125-6, 151, 229; II pp. 54, 64-5, 85-6, 127-8). An early symphony by Hiller was performed at a concert on 9 April 1835 together with works by Berlioz, who reviewed the symphony in detail (Journal des Débats, 25 April 1835). Of Hiller’s piano playing Berlioz says elsewhere (Critique Musicale II p. 65):

The distinguishing mark of his talent is not the passionate exaltation of Liszt, nor the capricious grace of Chopin, but rather a wise correctness and an admirable intelligence, which lead him to perform every composer in accordance with the style that is appropriate to him. He penetrates deeply into the spirit of the work and reproduces without any modification both its form and its purpose. Such a talent is assuredly as rare as it is valuable, and it can well be imagined that composers will rank it among the most precious.

After Hiller’s departure from Paris in 1835 the two men lost contact for several years, but their friendship was easily rekindled given a suitable occasion. When Berlioz started on his travels to Germany in December 1842 he contacted Hiller, at the time in Frankfurt (CG no. 785), and had the pleasure of meeting him again there (Memoirs, Travels to Germany I, First letter). Hiller himself later wrote an account of Berlioz’s visit; he relates in particular the story of how Berlioz sought to escape from Marie Recio after his stay in Mannheim but was quickly caught up by her in Weimar.

Another gap in their correspondence followed till Hiller eventually settled in Cologne as Kapellmeister in 1850 when he tried unsuccessfully to entice Berlioz to visit Cologne (CG nos. 1344, 1355). Hiller was back in Paris to promote his own music and give concerts in the years 1851 to 1853 (CG nos. 1383, 1384, 1516, 1556, 1562). Berlioz had occasion to mention a number of these in his articles in the Journal des Débats, and his references to Hiller as pianist, composer and musician were unfailingly complimentary (see especially Débats, 23 February 1851, 7 January 1852, 17 March 1853). In June of 1853 Hiller was in London and present at the abortive performance of Benvenuto Cellini at Covent Garden on 25 June.

There is another gap in their correspondence till 1863, but references in other letters of Berlioz suggest that their relations came under a cloud in the mid 1850s as an indirect result of Berlioz’s growing closeness to Liszt in the years 1852-1856: Hiller took sides against Liszt in the rift that developed in German music, and allusions in Berlioz’s letters to Liszt in 1855 suggest that Berlioz had come to suspect Hiller, possibly under the influence of Liszt. In CG no. 1975 (7 June), he refers to Hiller as ‘our good friend Rosencrantz-Hiller’, and in CG no. 2012 (10 September) he refers ironically to ‘our good Hiller, who will give us support on which we can count’. It is not clear what Hiller had done to provoke these comments. More definite evidence of Hiller’s hostility to Liszt, if not to Berlioz himself, came in June 1857 when Liszt sought to put on a complete performance of L’Enfance du Christ in Aachen despite local opposition and was met with an organised display of hostility in which Hiller himself was involved (CG nos. 2209, 2219, 2232, 2233). Berlioz does not actually refer to the role of Hiller in this episode, nor apparently did Hiller himself, though it seems that Hiller soon tried to mend fences with Berlioz: the following year Berlioz writes to Richard Pohl ‘Are you going to the Cologne festival? I have been invited by the committee and our good friend Hiller’ (CG no. 2289, 28 April).

The correspondence between Berlioz and Hiller eventually resumed in 1863 when Hiller, evidently still trying to move closer to Berlioz, sent one of his scores to Berlioz to deposit in the Conservatoire library and suggested he should visit him when in Cologne (CG no. 2737, 10 June). Berlioz responded positively and specified that he had not been in Cologne for a long time (CG no. 2750; 8 July). The comments he made on Hiller’s music in the letter of 8 July are significant: ‘Your work is written in a clear and firm style; I congratulate you for preserving it amid the tendencies to mayhem [tendances charivariques] which have manifested themselves for such a long time among the new German composers’ (CG no. 2750). The allusion to Wagner is transparent, and is an indication of the growing distance between Berlioz and Liszt at this period. Hiller must have felt that his old friendship with Berlioz was reverting to its original state.

![]()

In April 1866 Hiller was back in Paris and in July he and Berlioz served on an international panel judging entries for a prize in religious composition at Louvain in Belgium (cf. CG 3149, 25 July). It was probably on this occasion that Hiller pressed Berlioz to come and conduct some of his works in Cologne the following February, after his visit to Vienna in December 1866 to perform the Damnation of Faust.

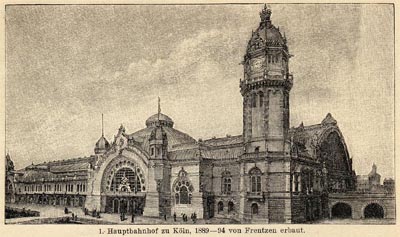

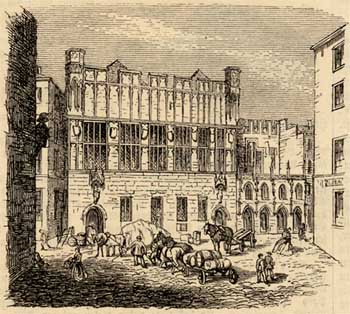

Berlioz was tempted yet also reluctant: he was tired and frequently ill, and the trip was very nearly cancelled at the last moment (CG no. 3219, 6 February 1867). But Hiller’s presence as Kapellmeister in Cologne provided in itself a guarantee and an incentive. A series of letters of Berlioz to Hiller discuss in detail the arrangements for the visit and the music to be played (CG nos. 3181, 3184, 3186, 3212, 3216, 3220): the complete Harold in Italy and the duet from the end of Act I of Béatrice et Bénédict. The concert was also to include Mendelssohn’s overture Ruy Blas and excerpts from Spontini’s Olympie. Eventually Berlioz left Paris (certainly by train) on 22 February at 5 in the evening and arrived early the next morning in Cologne, where he stayed at the familiar Hôtel Royal (CG no. 3221). His concert almost certainly took place at the Gürzenich, whose musical director was Hiller himself.

No letters of Berlioz survive from the time of his stay in Cologne, though back in Paris he wrote to Estelle Fornier of his success there (CG no. 3223, 4 March 1867):

[…] I am back from Cologne where I was asked to conduct two of my works at the ċoncert on 26 February. I refused twice, they insisted a third time, and finally I ventured to undertake the journey without really knowing what would come of it. I was violently ill more than once, but in the end I managed to hold three rehearsals and perform on the evening of the concert. The Kapellmeister, my old friend M. Hiller, about whose true feelings I had my doubts [probably a reference to the Aachen episode], gave me on the contrary a warm and friendly welcome. We have renewed our old links. His orchestra was outstanding and the public very warm. My scene from Béatrice et Bénédict and my large symphony on Harold in Italy were magnificently performed. As in Vienna, I was entertained to a sumptuous dinner. Fanfares, speeches, etc. […]

He gives a similar account to one of his nieces, and adds ‘And yet I was very ill, and had no strength except when conducting this superb orchestra which I was far from expecting on the banks of the Rhine’ (CG no. 3225, 6 March; cf. also nos. 3227, 3234).

Hiller’s own memoirs, published years later (Künstlerleben, 1880; see above) give a similar account of Berlioz’s stay and the reception he received. Here is a translation (by Michel Austin) of the relevant section (pp. 94-5):

It had long been my wish to invite Berlioz to Cologne to perform one of his works. I wanted to experience the double joy of introducing our orchestra to the friend of my youth, and to introduce him to the orchestra. In the autumn of 1866 I was finally able to carry out the necessary steps. There developed a correspondence between us over how, what and when this could be done. I must admit this was not easy to accomplish, as Berlioz raised objections against non-existent problems and had doubts about matters where there was nothing to be questioned. As I managed to reassure him completely, I had at least the satisfaction of receiving from him a letter with the words: you are the best friend anyone could find [CG no. 3220]. He promised to come, and then in February 1867 the days he spent with us were unforgettable. One can hardly imagine a more rapid succession of emotions and circumstances than what we experienced with him at that time. Whenever I visited him in his room to fetch him I found him tired and miserable; whatever the time of the day he was usually in bed. He complained that he did not want to take anything and could hardly speak, yet half an hour later he was taking food, admittedly half protesting, but with as much zest as the landlady could possibly wish. Whether he was telling a story or reflecting, he would chat with all the lively and even forceful eloquence that was peculiar to him. One morning he dragged himself with difficulty to the orchestral rehearsal (he did not want to go in a carriage), yet hardly had he ascended the conductor’s podium that he was like transformed, alive, energetic and bubbling over. He reminded me of the swan who raises himself with difficulty and plods his way ponderously to the water, but as soon as he has let himself go glides over the watery surface with majestic calm. Admittedly repose was not Berlioz’s distinguishing mark; but an orchestra is also not a lake, even if the heavens are reflected in it. Fortunately the performance of his symphony Harold in Italy was excellent (Königslöw played the solo viola part); the composer was greeted with heartfelt warmth and left feeling satisfied and grateful.

On his return to Paris Berlioz sent Hiller copies of his three published literary works (Les Soirées de l’orchestre, Les Grotesques de la musique and À Travers chants) as well as the new edition of the Requiem published by Ricordi in Milan (CG no. 3226, 12 March). In September Hiller was one of the friends of Berlioz who encouraged him to accept the invitation to go to Russia for what proved to be the last concert tour of his career (CG no. 3274). Hiller evidently hoped to entice Berlioz to stop again in Cologne on his way to Russia in November 1867, but Berlioz was unable to accept (CG no. 3281, October 1867, the last preserved letter of Berlioz to Hiller). The concert of February 1867 was thus the last to be conducted by Berlioz in Germany, nearly forty years after his first meeting with Hiller in Paris.

![]()

All the pictures displayed below have been scanned from postcards and prints in our collection. All rights of reproduction reserved.

This card was posted on 11 May 1919.

![]()

The Berlioz in Cologne page was created on 1 June 2005; revised on 1 May 2008. Revised and enlarged on 1 February 2024.

© Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb. All rights reserved.