![]()

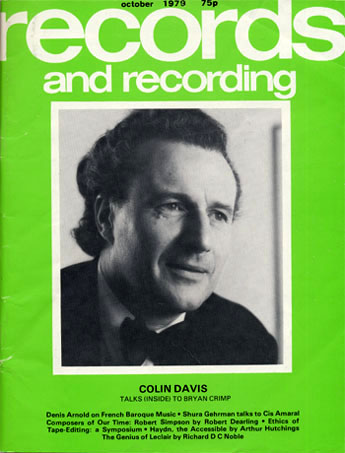

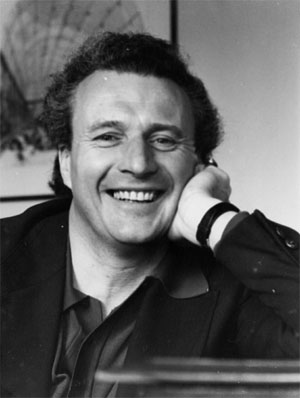

Conductors: Sir Colin Davis (1927-2013)

|

Conductors: Sir Colin Davis (1927-2013)

|

|

Career

Sir

Colin Davis on Berlioz

In Memoriam Sir Colin

Illustrations

An

autograph letter of Sir

Colin Davis

This page is also available in French

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.

![]()

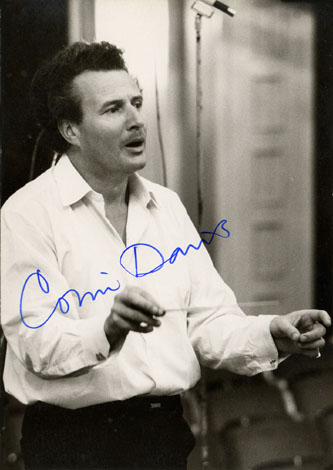

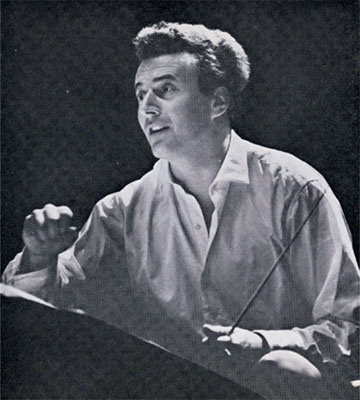

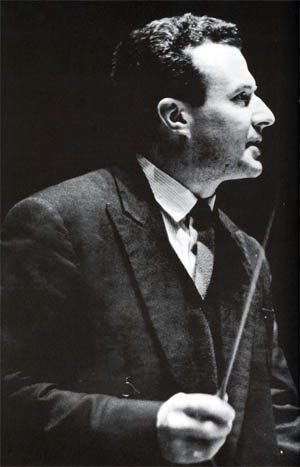

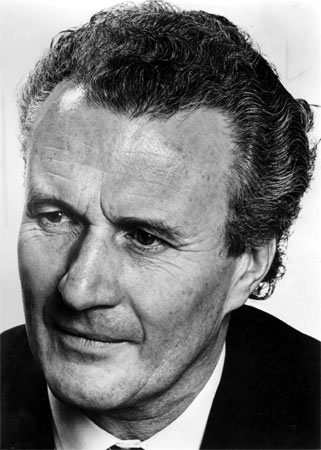

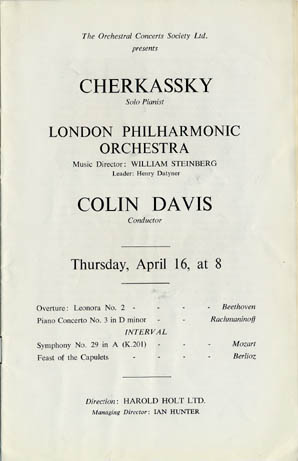

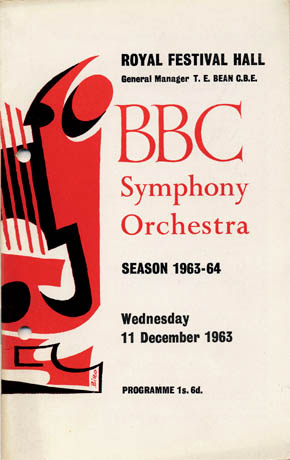

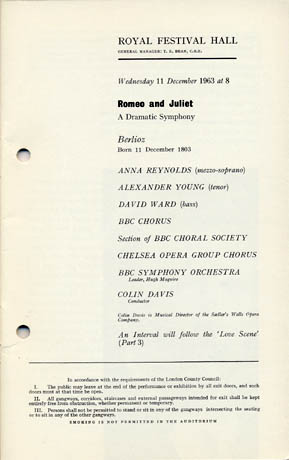

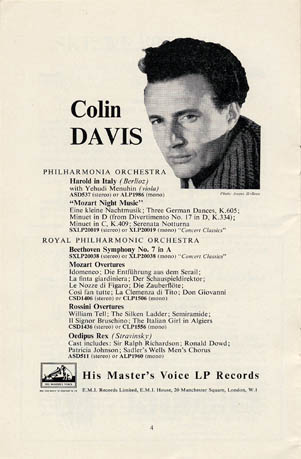

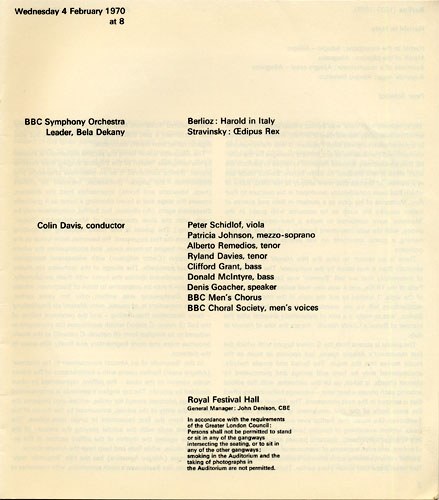

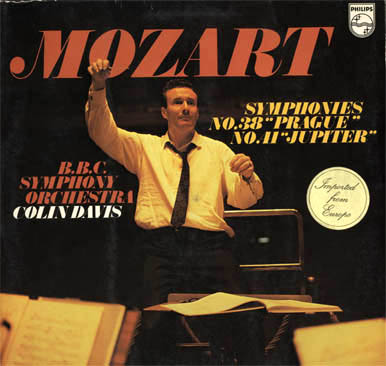

British conductor, internationally recognised as the foremost interpreter of Berlioz of his time, Sir Colin Davis has done more than any previous conductor to establish Berlioz as a major composer who can stand in the company of the greatest. Davis first studied the clarinet at the Royal College of Music. In his early twenties he conducted the Kalmar Chamber Orchestra and the Chelsea Opera Group. In 1952 he made his appearance at the Royal Festival Hall as one of the conductors of the Festival Ballet season. He was appointed as assistant conductor of the BBC Scottish Orchestra in 1957. The breakthrough came in 1959 when he stepped in to conduct a performance of Don Giovanni at the Festival Hall after Otto Klemperer had cancelled on account of illness. The performance was greeted by reviewers with acclaim. In 1961 Davis became musical director of Sadler’s Wells Opera (later to become the English National Opera), and in 1967 he took up his appointment as chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. This was followed by the musical directorship of the Royal Opera House Covent Garden (1971). In 1986 he went to Germany to take up the position of principal conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Munich, and then of the Dresden Staatskapelle. In 1995 he returned to Britain to take up the position of principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra; he was succeeded by Valery Gergiev in January 2007. Over his career he has conducted at one time or another many of the world’s great orchestras.

Colin Davis was created a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1965, knighted in 1980 and awarded in 2001 the CH (Order of the Companions of Honour), which is awarded for service of conspicuous national importance, and is limited to 65 people at any one time. He has also received honours abroad, in Italy, France, Germany and Finland. For example in 1999 he was made Officier de la Légion d’honneur.

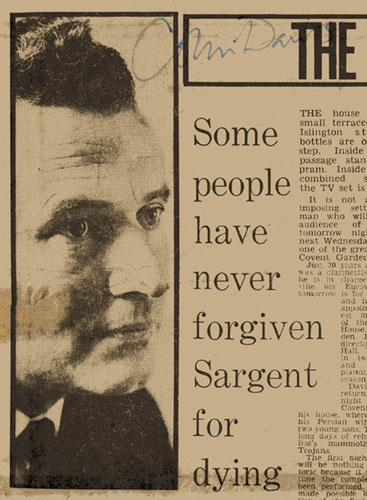

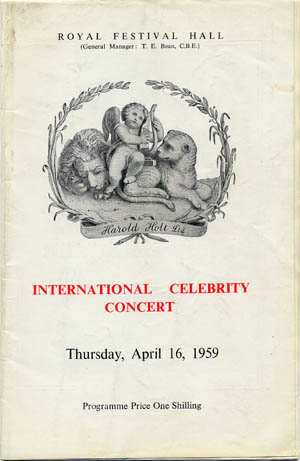

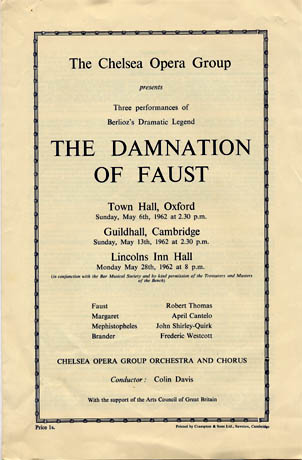

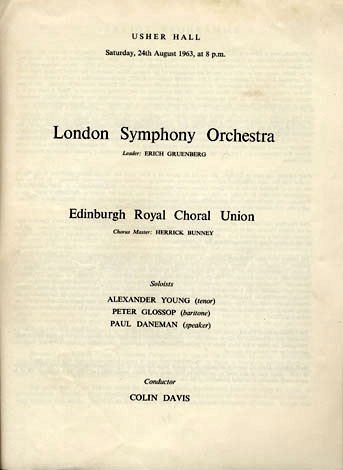

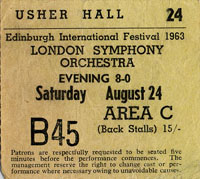

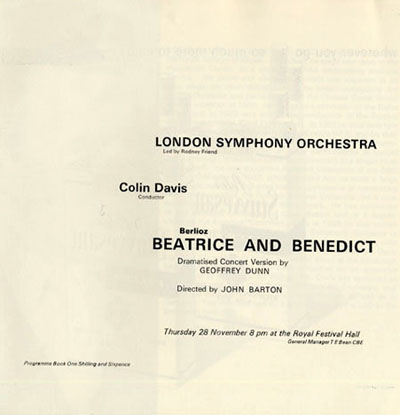

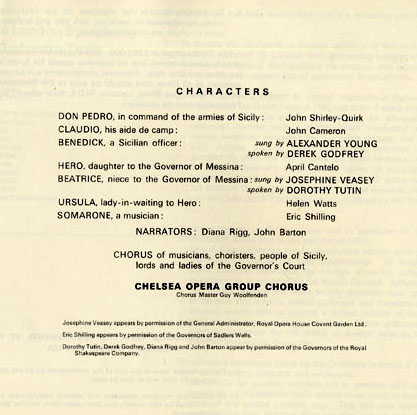

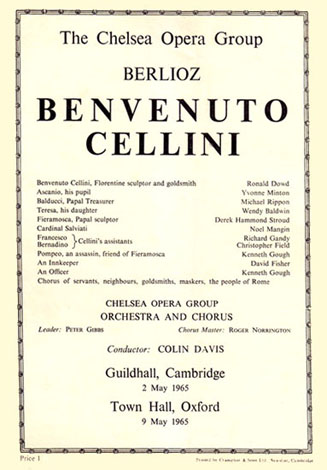

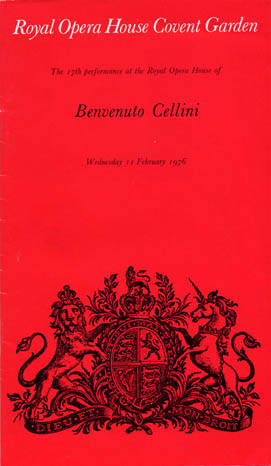

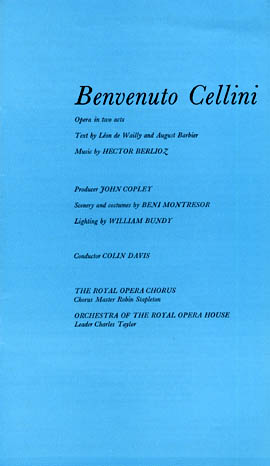

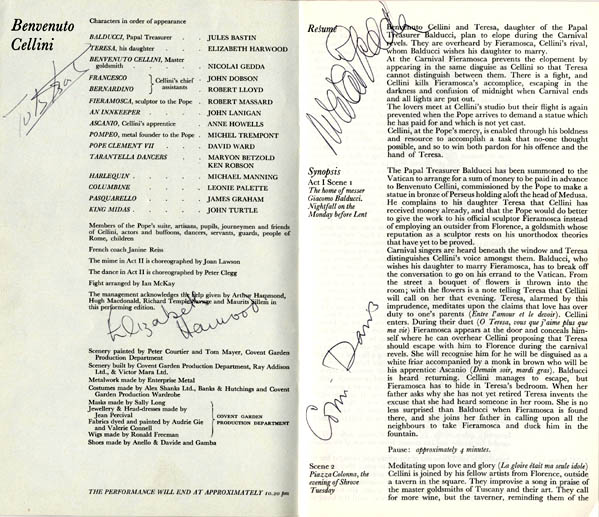

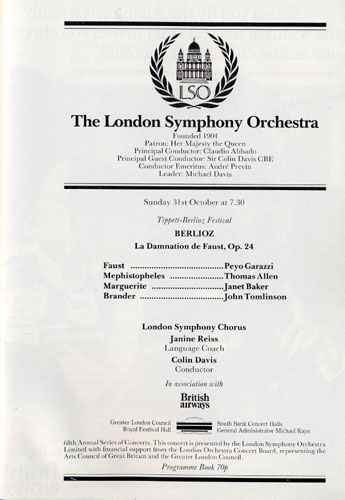

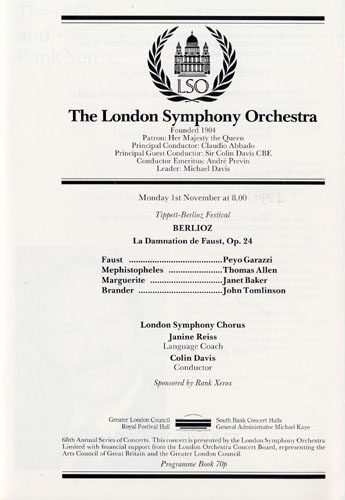

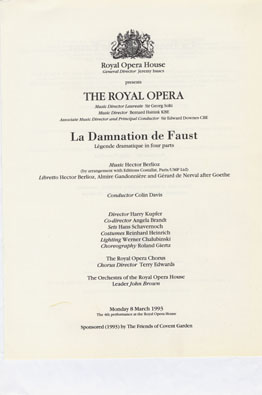

Like David Cairns, Davis discovered Berlioz independently for himself, and went on to develop his own distinctive approach to the composer and his music. The discovery began in 1951, when as a professional clarinetist Davis played in a performance of La Fuite en Égypte conducted by Roger Desormière. One of his early concerts to feature music by Berlioz was given at the Royal Festival Hall on 16 April 1959, when he conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra in an excerpt from Roméo et Juliette. In the early 1960s he conducted La Damnation de Faust, Roméo et Juliette and concert performances of Les Troyens and Benvenuto Cellini with the amateur Chelsea Opera Group, an ensemble formed by Stephen Gray and David Cairns in 1950. In an interview with a British newspaper (The Guardian, 21 September 2002), David Cairns made the following comment in connection with a concert performance of Don Giovanni with the Chelsea Opera Group:

I remember Stephen telling us about this wonderful young clarinetist called Colin Davis who understood Mozart better than anyone. He had conducted hardly at all before that but we took a gamble and immediately fell under the spell, not only of his musicianship but of his personality. We were all ex-Oxbridge and fairly inhibited and here was someone who wasn’t like that at all. Colin was much more abrasive then – he has always said things that come into his mind. During a performance in Oxford in 1950, attended by Isaiah Berlin, the playing became a little ragged so Colin just stopped and said: ‘Come on strings, you can do better than that’. The audience gasped.

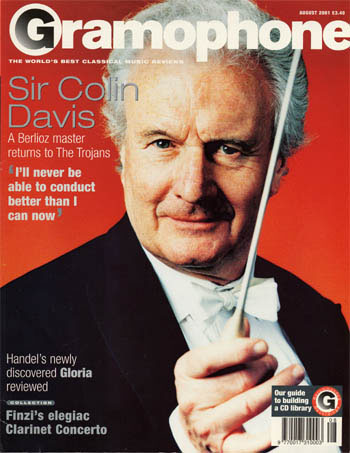

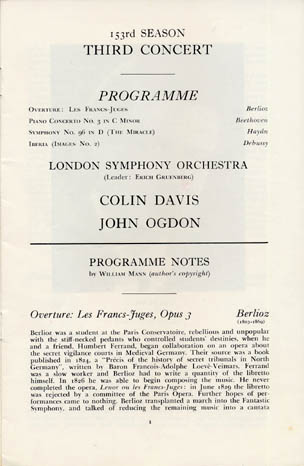

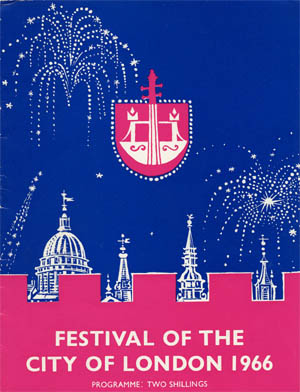

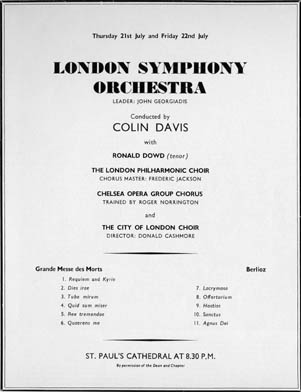

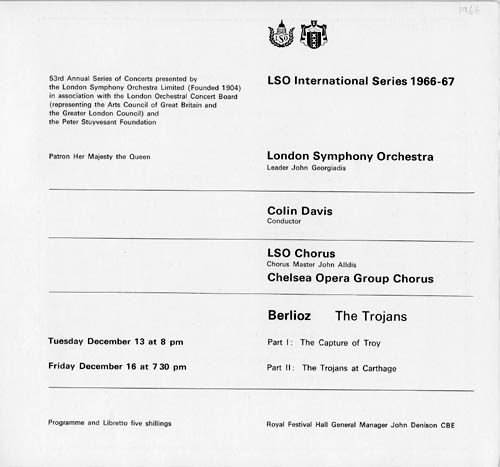

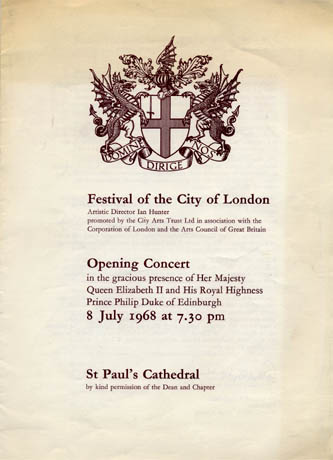

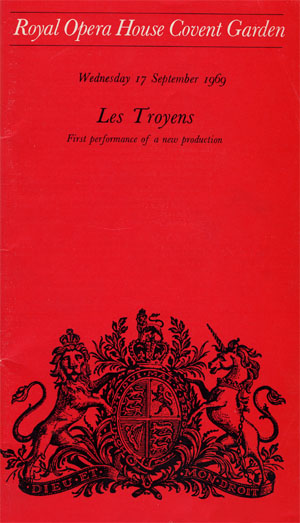

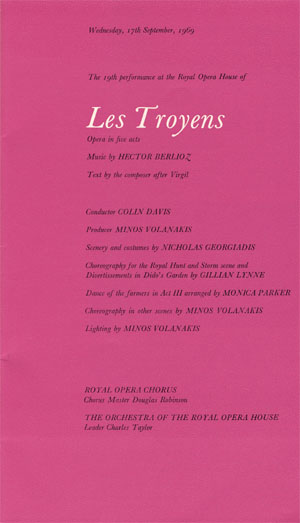

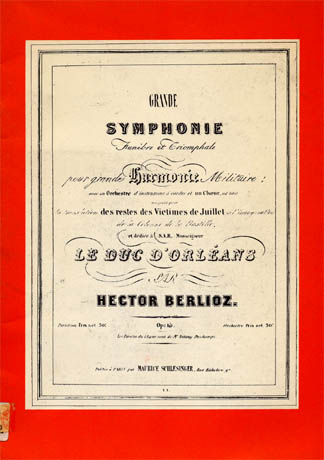

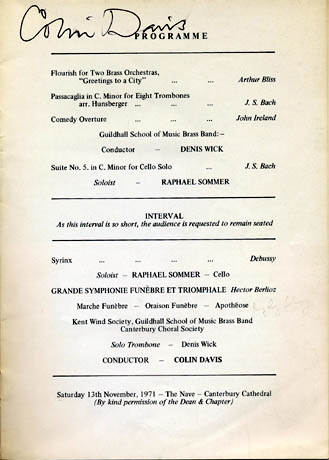

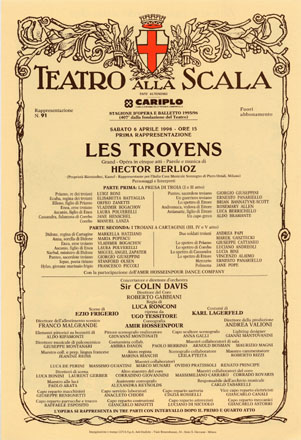

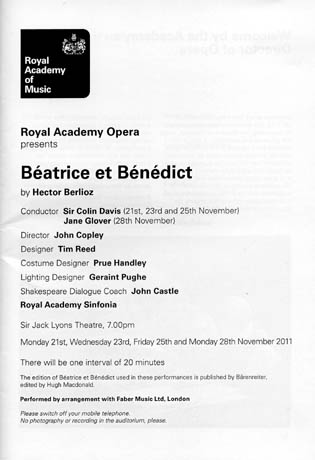

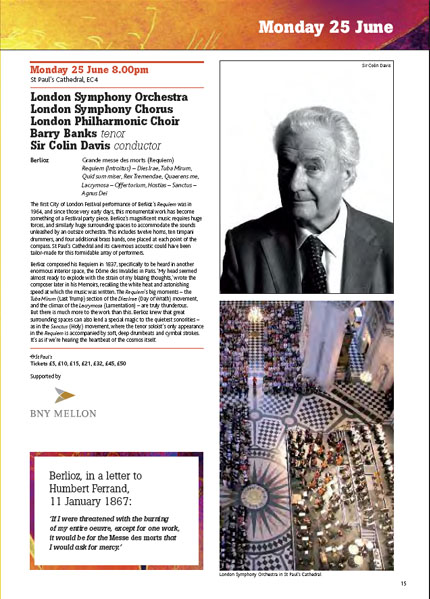

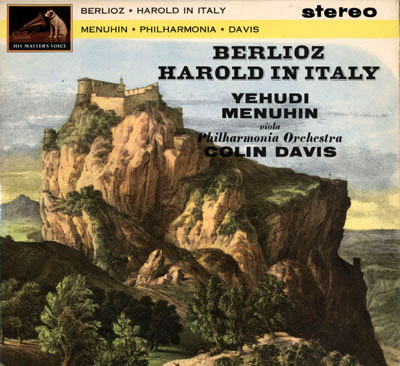

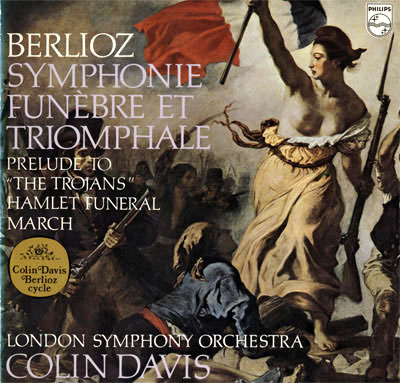

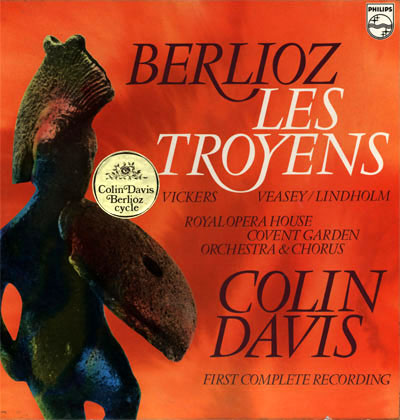

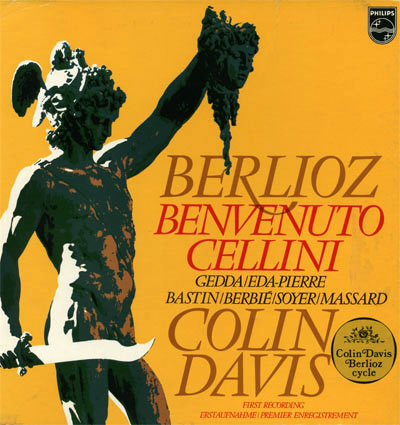

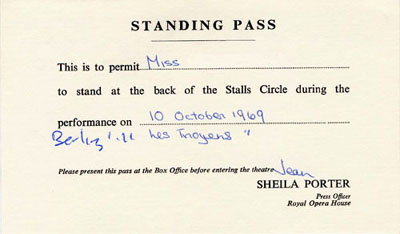

While earning praise as a conductor of other composers as diverse as Mozart, Sibelius or Stravinsky, Sir Colin made his mark as a particularly fine Berlioz interpreter in the 1960s. In 1964 he opened the Festival of the City of London with the Grande Messe des morts, and two years later he conducted two performances of the same work in St Paul’s Cathedral at the closing concerts of the same festival in 1966. In the same year, he conducted a performance of Les Troyens (in concert), with the London Symphony Orchestra on two evenings, on 13 and 16 December, having previously conducted the first two acts with the Chelsea Opera Group in Cambridge and Oxford (May 1963), with the New Philharmonia Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall (March 1965) and the Royal Albert Hall (November 1966). A concert performance of the last three acts with the LSO at the Royal Albert Hall in November 1967 was followed by another of the complete opera with the same orchestra in November 1968. The first ever complete staged performance of Les Troyens (in the original language) was given at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden on 17 September 1969. This was based on the score edited by Hugh Macdonald (see also a contemporary review of this production on the site). The 1969 production was recorded in the same year and released by Philips in their “Colin Davis Berlioz Cycle” series, the first ever complete recording of the work.

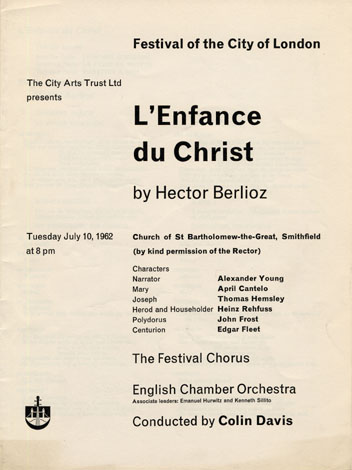

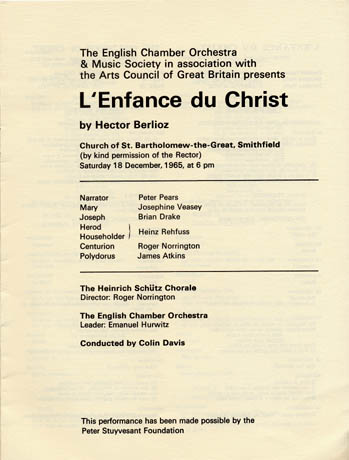

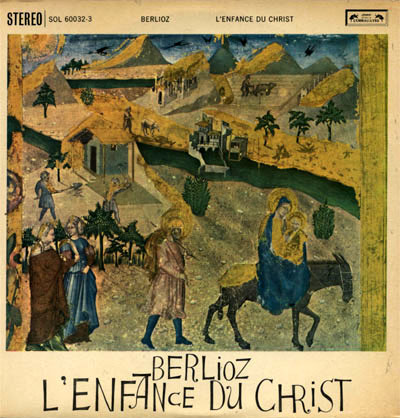

Since those early years of his career as a conductor, Sir Colin has been a champion of Berlioz at home and abroad; he has conducted and recorded more performances of Berlioz than any previous conductor. His Berlioz cycle of recordings with Philips includes almost all the works of the composer that require a conductor, except for a number of shorter vocal works, and many of these he has recorded more than once (for example, his first Berlioz recording, L’Enfance du Christ, was issued in 1961, and he recorded the work again in 1976 and 2006).

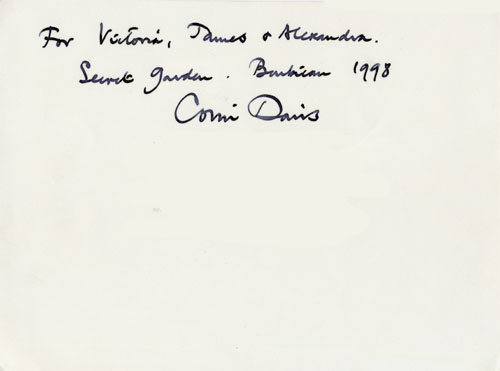

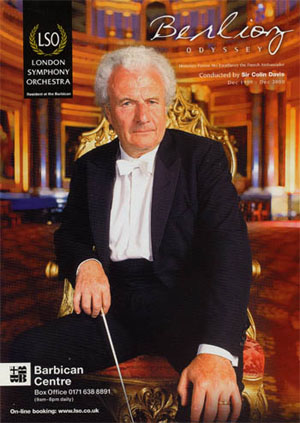

Sir Colin anticipated celebrations of Berlioz’s bicentenary by organising and conducting a year-long series of concerts with the London Symphony Orchestra under the title of Berlioz Odyssey, which began with three concert performance of Benvenuto Cellini in December 1999, and was completed with three concert performances of Les Troyens, with on the way performances of L’Enfance du Christ, Roméo et Juliette, Béatrice et Bénédict, Symphonie Fantastique, Harold en Italie, Les Nuits d’été, and La Damnation de Faust (all concerts were recorded live on the LSO’s own label). These performances were followed in 2001 by another performance of the Grande Messe des morts in St Paul’s Cathedral as part of that year’s City of London Festival (there are two reviews of this performance on this site).

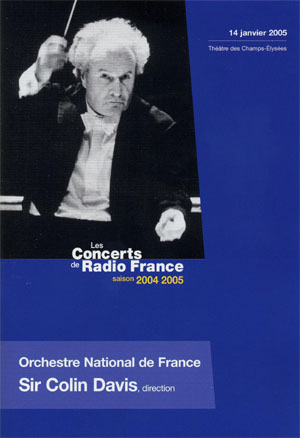

In the bicentenary year itself Sir Colin conducted the LSO in Harold en Italie, the Symphonie Fantastique, La Damnation de Faust and Roméo et Juliette at the Barbican Hall, and Les Troyens (concert performance) at the Royal Albert Hall as part of the BBC Proms 2003. In the same year he conducted, again with the LSO, Harold en Italie, the Symphonie Fantastique, La Damnation de Faust and Roméo et Juliette at the Lincoln Center, New York. From 2003 Sir Colin continued to conduct major works of Berlioz in London (with the LSO), France (including a Berlioz Cycle with the Orchestre national de France, 2004-2009), the United States (several concerts notably in New York but also elsewhere), Abu Dhabi (April 2010), and India (April 2010), the last two with the LSO in three performances of the Symphonie Fantastique.

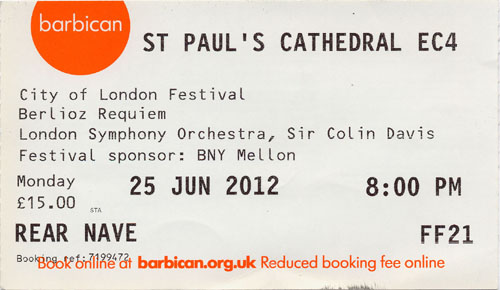

The last of work of Berlioz that Sir Colin conducted was the Grande Messe des morts at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London on 25 and 26 June 2012.

Thanks to the development of modern recording techniques, Davis’ interpretations of Berlioz have been preserved for posterity, and later generations will be able to judge for themselves the distinctive features of his Berlioz conducting. Most striking is not just the excellence of the playing, but the consistency of his performances over a period of more than four decades. As one example, the timing of the long slow movement of the Symphonie Fantastique is virtually identical in his four recordings of the work with three different orchestras, and at an interval of 37 years (1963, 1974, 1990, 2000; the timings are 17'06", 17'11", 17'08" and 17'13", though the other movements show more variation). Davis has thought through every work he has conducted, both in detail and in the overall design, and his view of individual works relates to his overall conception of Berlioz. As presented by Davis Berlioz is not the impulsive eccentric of ignorant popular mythology, but a composer fully master of his craft who has deep roots in the classical past as well as being a revolutionary innovator. The distinguishing marks of Davis’ Berlioz interpretations are clarity of structure, balance between opposing elements, precision of detail, and strength and consistency of the underlying pulse. It could be mentioned incidentally that as musicians Davis and Berlioz shared one element in common: their lifelong devotion to literature.

Performing styles and tastes will continue to evolve, for Berlioz as for any other composer. Indeed, a younger generation of conductors has explored approaches to Berlioz inspired by the period instrument movement which Davis himself has largely bypassed, though it is worth mentioning that some of these conductors (John Eliot Gardiner, Roger Norrington) did at one time play under Davis himself. But it can be confidently stated that whatever directions future performances of Berlioz may take, the interpretations of Davis will always remain a reference point against which others will be judged.

See also on this site (in English or in French) Berlioz and Colin Davis, Colin Davis’s Berlioz, Sir Colin Davis talks with Berlioz Biographer, Interview with Sir Colin Davis, a general assessment of his achievement for Berlioz, and articles or reviews of performances: the Requiem in 2008, Béatrice et Bénédict and a concert at the Opéra-Comique in 2009, Sir Colin Davis - A Discography.

![]()

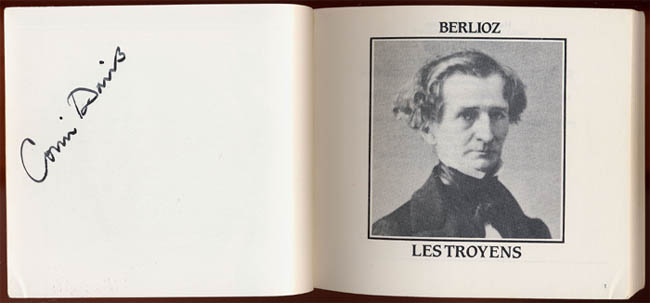

[The following is an excerpt from the booklet which accompanied the first complete recording of Les Troyens issued by Philips in 1969. The excerpt had originally been taken from an article in the magazine Music and Musicians, which has since ceased publication; we have been unable to contact their editors who hold the copyright.]

People have asked me so many times “Why Berlioz?” This is a brief attempt to throw some light on the question, even though, inevitably, it will be of small candle-power and more likely to cast shadow than illuminate.

Britons are, or were, brought up on Shakespeare, and the violent contrasts we encounter in his plays are something we recognise when we hear Berlioz’s music. We marvel at Shakespeare’s “King Lear,” and we do not question its acceptability. We marvel also at Berlioz’s “Roméo et Juliette,” but we argue bitterly over whether the work is a symphony, why Berlioz insisted on a prologue, or what induced him to write the finale at all. Only Berlioz dared mix his genres as Shakespeare did, and only Berlioz, I think, comes near to Shakespeare in his ability to suspend the apparent forward motion of time by the creation of a poetry of unbelievable, and scarcely bearable, beauty.

Berlioz, of course, did not fit into the general stream of the development of music in the nineteenth century. He is spoken of as a great romantic figure, but it is the classical aspect of his music that strikes me most forcibly. His world is an extension of that of Mozart, particularly the Mozart of “Idomeneo” — though in Berlioz Mozart’s suppressed demons are at large and the nostalgia for a world of lost innocence more painful. Also there is the same balance between melody, harmony, counterpoint, and colour. Of course the technique of composing is very different and, obviously, I am speaking very generally. Berlioz’s melodies are unlike anyone else’s, and Mozart might have raised his eyebrows at some of Berlioz’s harmonic procedures; but I would guess that he would not have minded having written the Nocturne from “Beatrice and Benedict” himself.

Another imaginative world that reminds me of Berlioz’s is that of William Blake, again as outwardly different from Berlioz as Mozart. Those violent landscapes of the prophetic books and the demi-gods that inhabit them, Los, Orc, Urizen (definitely suffering from Berliozian spleen in his fallen world), which contrast with the vision of the restoration of creation to primal innocence, call upon so many correspondences. Not only that — Blake’s obsession with line is comparable to Berlioz’s reliance on melody: the lineaments in Berlioz’s music have all the definition and courage that Blake would have liked. Both were in search of love through imagination and the creative act. Both attempted to transcend the material Satanic fact, Blake through Christ, Berlioz through beauty. Blake dreamed of his New Jerusalem, Berlioz of a land, unlike his own, where art would at least be taken seriously. Each would have welcomed the other in his City of Imagination…

Each person asks of music that which reflects the makeup of his own psyche. Those who do not wish to be disturbed by music will not take to Berlioz; neither will those who seek for logical patterns, nor those who wish to indulge their favourite emotions; but those who admit to themselves the inherent discrepancies of this fallen universe, who are no longer surprised that love and hate, violence and tenderness, Christ and the Devil, each call the other into being, will find in Berlioz’s music a reflection of their knowledge. They will follow the soaring lines of his melodies through the unquiet harmonies to the humble acceptance of the cadences that bless their completion. They will understand that “L’enfance du Christ” is impossible with Mephisto, and they will, above all, be grateful for those moments of utter beauty which reflect Berlioz’s life-long search through an enhanced sensuality for an ideal love that passeth all understanding.

Colin Davis

![]()

Sir Colin Davis passed away on 14 April 2013.

See also In Memoriam Sir Colin: Je ne vous verrai plus by Christian Wasselin, in the French version of this page.

![]()

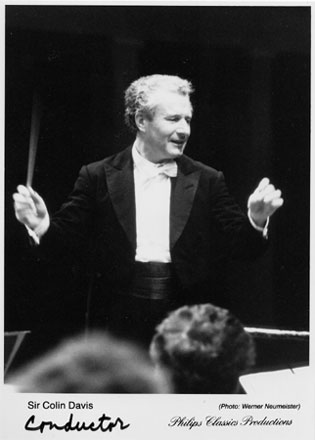

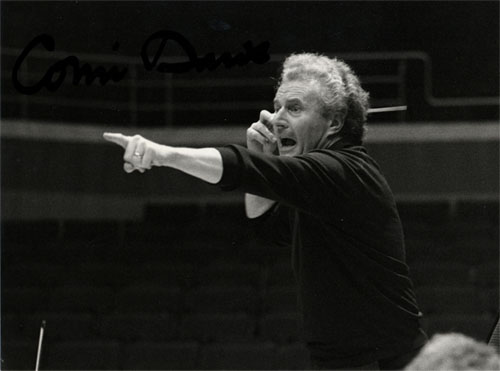

All the pictures on this page have been scanned from original photos, documents, concert programmes and recordings in our own collection. All rights of reproduction are reserved.

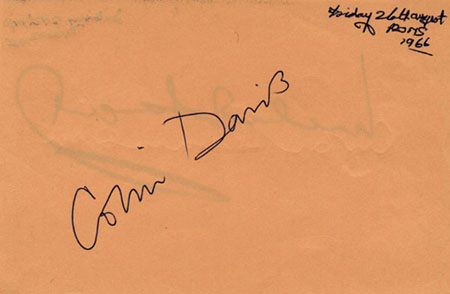

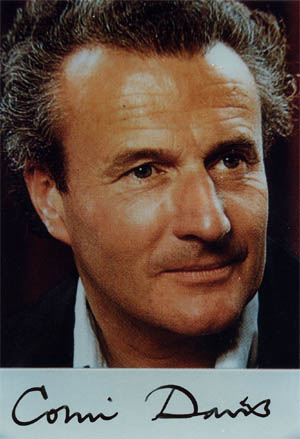

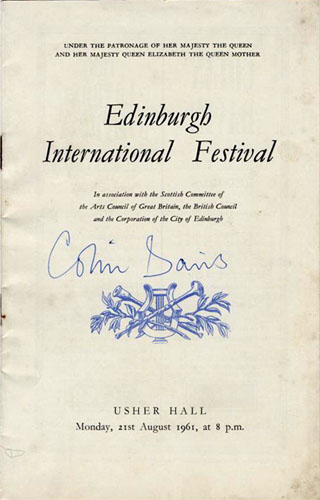

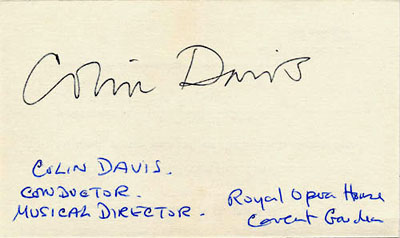

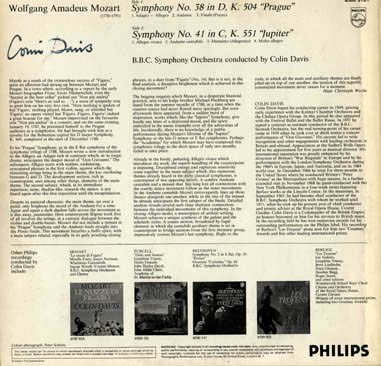

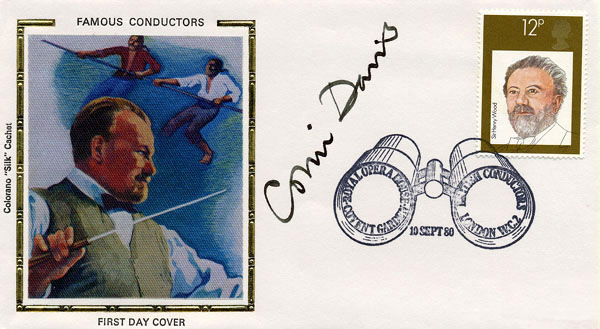

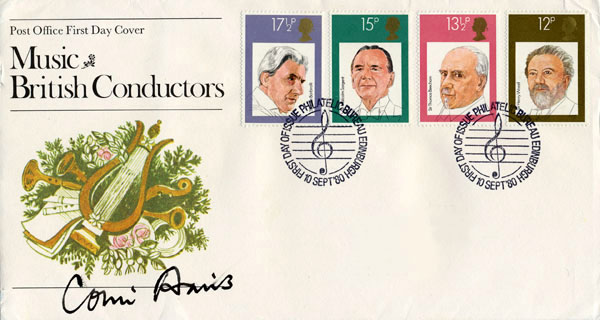

Autograph of Sir Colin Davis, signed on 26 August 1966 at the BBC Proms

At this Proms, Sir Colin Davis conducted the BBC Symphony Orchestra in Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins, Michael Tippett’s The Vision of St Augustine, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, Eroica

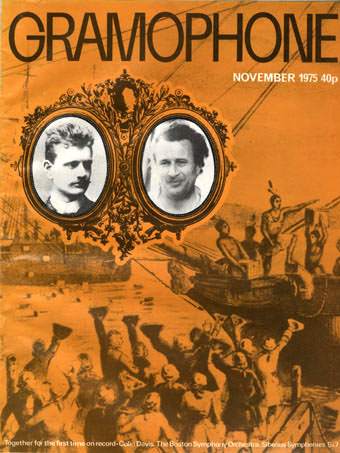

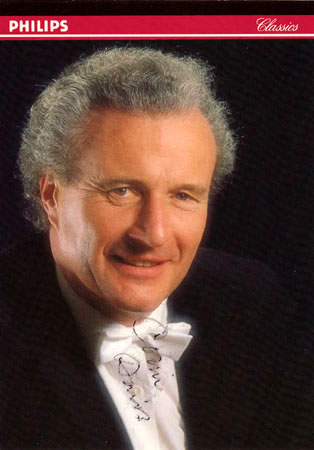

The text on the cover page reads: Together for the first time on record – Colin Davis, The Boston Symphony Orchestra: Sibelius Symphonies 5 & 7.

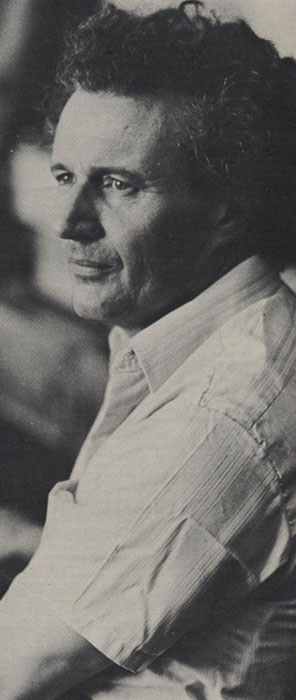

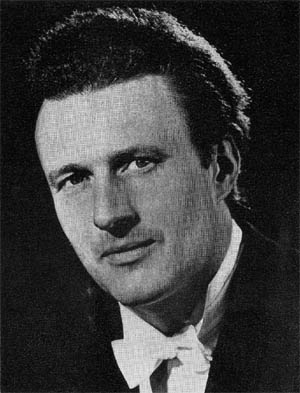

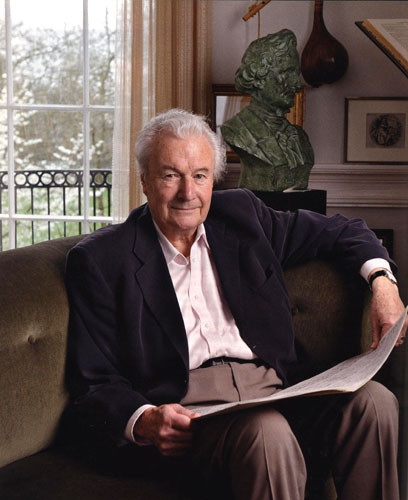

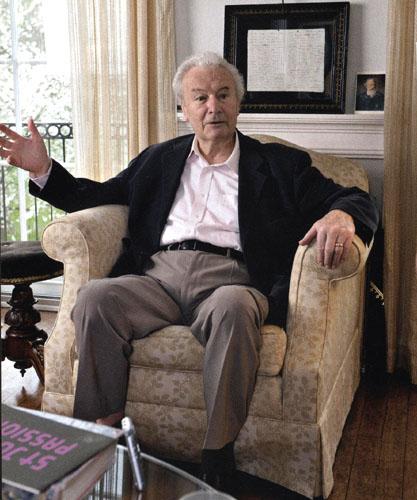

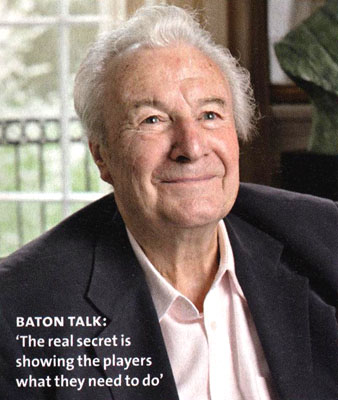

The following three photos have been scanned from our own copy of the June 2011 issue of BBC Music Magazine (pages 35, 40 and 39 respectively). BBC Music Magazine holds the copyright for all three photos.

Photo: © BBC Music Magazine

Photo: © BBC Music Magazine

Photo: © BBC Music Magazine

Photo: © Sarah Lea / The Guardian

Photo: © Festival of the City of London

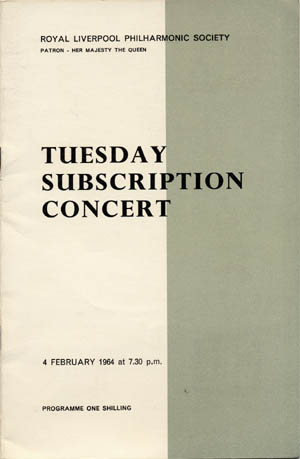

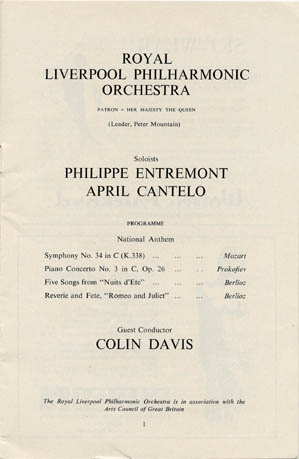

The soloist in Les Nuits d’été was April Cantelo, Sir Colin’s first wife. Five of the songs were included in the concert: Villanelle, Le Spectre de la rose, Sur les lagunes, Absence and L’Île inconnue. The excerpts from Roméo et Juliette were: Roméo seul – Tristesse – Concert et bal – Grande fête chez Capulet.

In this concert, Sir Colin conducted the London Symphony

Orchestra and the John Alldis Chorus in performances of La Fuite en Egypte

(part II of L’Enfance du Christ), Hélène,

La Belle voyageuse, Le Jeune pâtre breton, La Mort d’Ophélie,

La Captive, Zaïde, Les Nuits d’été

and Sara la baigneuse, with Sheila Armstrong, Josephine Veasey, Robert

Tear, Martyn Hill, Thomas Hemsley and Michael de Coverly.

This production was by arrangement with Editions Costallat, Paris/UMP Ltd.

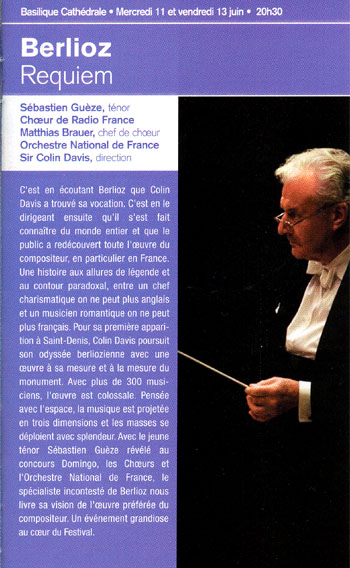

This concert was the first time that Sir Colin participated in the Saint-Denis Festival, and for which he chose to conduct the Requiem. The first half of the text in the programme reads:

C’est en écoutant Berlioz que Colin Davis a trouvé sa vocation. C’est en le dirigeant ensuite qu’il s’est fait connaître du monde entier et que le public a redécouvert toute l’œuvre du compositeur, en particulier en France. Une histoire aux allures de légende et au contour paradoxal, entre un chef charismatique on ne peut plus anglais et un musicien romantique on ne peut plus français.

It was by listening to Berlioz that Colin Davis found his vocation. It was subsequently by conducting him that he made his name throughout the world and that the public, especially in France, rediscovered the composer. This is a story that has the air of a legend and a paradoxical character, the combination of a charismatic conductor who is quintessentially English and a romantic composer who is quintessentially French.

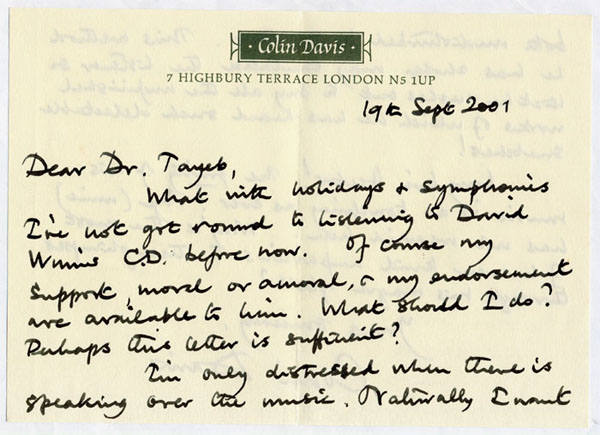

![]()

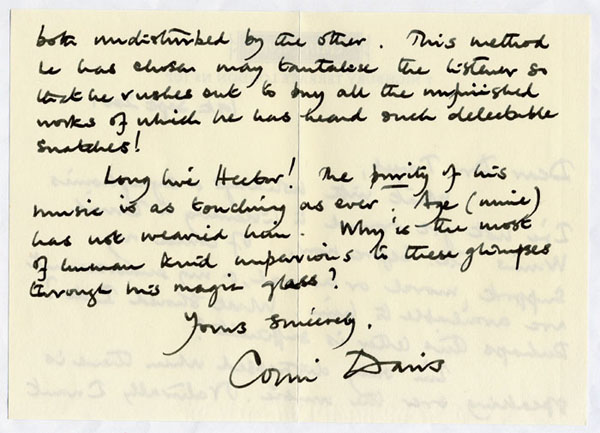

Sir Colin’s letter was in response to a request by us on behalf of Mr David Winn for Sir Colin’s support for his extensive radio project in Canada, ‘The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz, told in his own Words and Music, and in the Words and Music of Others,’ a series for radio in twenty-one parts of 30 minutes each.. We had also sent Sir Colin a sample of audio CDs of the project supplied by Mr Winn.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir

Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Page Berlioz: Pioneers and

Champions created on 15 March 2012; this page created on 15 March 2012,

enlarged on 1 June and 6 October 2014, 7 October 2016 and 1 January 2017.

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.