![]()

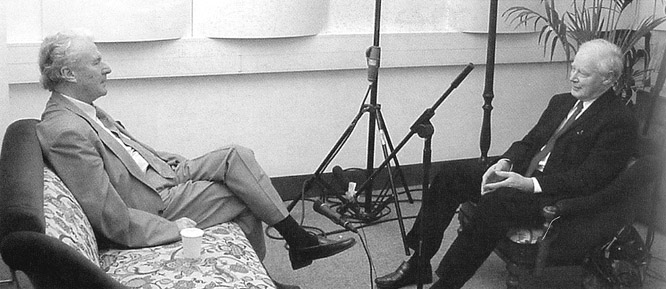

This page presents the edited text of an interview which first appeared in the programme booklet for the concert performances of Les Troyens in December 2000 given by Sir Colin Davis and the London Symphony Orchestra which concluded the year-long Berlioz Odyssey series. We are most grateful to Sir Colin, Mr. David Cairns and the LSO for granting us permission to publish this text and the accompanying photograph on this site. All rights of reproduction are reserved.

David Cairns: So the great journey has reached its end. What are your feelings about the composer after a year of Berlioz?

Sir Colin Davis : He’s a much greater composer than I ever thought he was. There is no other music like it. I don’t know a moment when Berlioz is ever plodding or pedestrian. He always comes up with some startling new idea which still surprises me, still gives me immense pleasure.

I think the thing that has grown upon me, especially in The Trojans, is the really human quality of what he writes for his characters. That little scene with Ascanius, when he presents the trophies from Troy for example, is one of the most touching things in the whole score. And he is able to depict and follow the various changes in emotion and mood – of his women particularly. It’s absolutely astounding: its like Mozart really. So I’m thoroughly convinced. In fact I’m a little alarmed at what on earth I’m going to do afterwards . . . if anything.

DC: I suppose that in the years when we were trying to persuade people that Berlioz was a great composer, and not just a maverick or an oddity, we perhaps spent too much time and energy emphasising that he wasn’t a crazy guy: that he knew what his pieces were doing, that they didn’t just flout the rules, they obeyed their own rules. We wanted to persuade people that he wasn’t out on a limb totally unlike other composers.

CD: But he was unlike anyone else, wasn’t he? Berlioz – with his unique voice, and with the kind of music he was writing – had to be especially in control. Rather like Sibelius, another wild spirit, he had to have enormous discipline to get down onto the paper what was burning in his mind. That makes what he’s trying to express in his particular way something that is exhilarating. I’m swept off my feet again. I’m thinking ‘what is it going to be like this time!’ – and off we go. Like the hysterical onrush of the Trojans onto the plain before Troy at the beginning of The Trojans. You look at it, you’ve heard it, you know what it sounds like, but when you hear it again, you’re swept along with it.

DC:People used to think that these heroic, ancient-world operas somehow had nothing more to say to us. They said that about Mozart’s Idomeneo, that it was a beautiful piece but not connected with our world any more. But I feel the great convulsions of the 20th century have made these epic works – of the migrations of people, the fall of cities, the great upheavals – thoroughly germane to us now.

CD: Yes, the stories of conflict between father and son, the man who vows something stupid which costs him his kingdom, these things are with us all the time. The Trojans is the great warning, the great piece of technology which created our civilisation. Wheels and mathematics – and all these other disasters which have given rise to the technological world – were first invested in a mechanical horse!

DC: What are your thoughts on concert performances as opposed to fully staged productions?

CD: In many ways concert performances are more satisfactory. They’re not subject to the vagaries of what is happening on the stage nor the appalling problems of distance between the orchestra and the singers, or the obstacle of perverse productions. You come back to the reason why opera is done at all, which is because the music is so good.

DC: Can you mention some of the highlights for you in The Trojans?

CD: The beauties of the piece just multiply as we go through it. We have this fantastic scene for Cassandra at the beginning of the piece, which is balanced by Dido’s public appearance at the beginning of Part 2; and then the duet and then the irruption of the Trojans, and then comes swarthy Iarbas who’s threatening the crops and the beasts. And then another masterpiece, the Royal Hunt and Storm, and then the whole seduction of the garden scene, and then the agony of the last act. It’s endless.

DC: It’s interesting that Berlioz depicts the utter finality of Dido’s decision that her life is over, with music that’s absolutely pared down. The scoring for cor anglais and clarinet and violas is astonishing.

CD: It bleeds to death at the end. It destroys me. And Dido’s soliloquy when she stabs herself is the last wonder.

DC: You’ve spent a long time with Berlioz, the man as well as the composer. Any thoughts about the relationship between Berlioz and his works?

CD: The lives of all these wonderful men are just like ours. There’s a fairly obvious split between their imaginary world and their pragmatic world. Sometimes the exaltation of creating something is so strong that you reckon you can carry the whole world away with it. I think they all, especially Berlioz, suffered from this. There he is on a high mountain and tomorrow he’s at the bottom of a pit. And how anybody can lead a reasonably normal life under those conditions is beyond me. The ideas are flying across and you’ve just got to grab them and write them down. You are, momentarily, God; then you look around afterwards and realise that it was not you who peopled the world in this way.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. Reproduced with kind permission of Sir Colin Davis, Mr. David Cairns, and the LSO. All rights are reserved.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created in August 2002.

![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Contributions Originales

Retour à la page Contributions Originales

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil