A review by

Margaret Davies

© 1969 Margaret Davies

© 1969 The Illustrated London News

Published in

The Illustrated London News, 27 September 1969, pp.

36-37![]()

THE NEW PRODUCTION OF Les Troyens which opened the season at the Royal Opera House on September 17 also constitutes this country’s major contribution to the Berlioz centenary celebrations. The French composer’s great epic masterpiece can now, and for the first time in its ill-fated career, be heard in its entirety in the original language in an opera house.

Berlioz wrote in 1854: “Since 1851 I have been tormented by the idea of a vast opera, for which I should like to write both the words and the music.” He went on, “The subject seems to me grandiose, magnificent, and deeply moving.” It was to re-tell the story of the fall of Troy, of Aeneas’ escape with his followers to Carthage, of his love for Dido, Queen of Carthage, whom he finally deserted, and of her death. Berlioz based his libretto on Virgil’s account of Aeneas’ adventure in the Aeneid, which he had known since his boyhood, but he also borrowed from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice the scene in Act V between Jessica and Lorenzo for the great love duet between Dido and Aeneas Par une telle nuit.

The opera was completed in 1858, after three and a half years of work. Berlioz was well aware that there was much prejudice in Parisian musical circles against his compositions, in particular from the director of the Paris Opéra. He submitted the manuscript of Les Troyens to the Emperor Napoleon III who displayed some interest in the work and promised to read it if he found the time. He did not do so, and the composer’s hopes of Imperial patronage were doomed to disappointment. The manuscript was passed on to a functionary in the administration of the national theatres where it was scorned and ridiculed. Rumours circulated in Paris that the opera lasted eight hours, would need two companies the size of the Opéra’s to perform, that Berlioz was demanding 300 extra chorus singers, and much more.

Discouraged by the unsympathetic treatment meted out to him, Berlioz despaired of ever seeing his work performed at the Opéra, and after five years of fruitless waiting he eventually agreed to its being staged at the smaller Théâtre Lyrique which was directed by Leon Carvalho, although he realized that the resources of that theatre were far from adequate to do the opera justice. So it was on June 1, 1863 that Berlioz read his libretto to the assembled company and rehearsals began.

But he was still far from achieving his ambition, for he was persuaded by the management of the Théâtre Lyrique to divide the work into two parts: La Prise de Troie, which included the first two acts of the original score, and Les Troyens à Carthage, comprising the remaining three acts. And in spite of the director of the theatre having obtained a state grant of 100,000 francs to produce the opera, this sum was only considered sufficient to mount the second part, Les Troyens à Carthage. Even this was further drastically pruned during the course of the rehearsals, and it was a cruelly mangled version which had its first performance on November 4, 1863, with Charton-Demeur as Dido and Monjauze as Aeneas.

A vocal score published at the time featured these cuts, and although Berlioz hoped to see the full score published complete this was not to come about during his lifetime, not in fact until this centenary year. It is this Barenreiter score which is being used at Covent Garden.

Between the premiere at the Théâtre Lyrique and December 20, 1863, 22 performances of Les Troyens à Carthage were given before the work was dropped. On the whole it was not unfavourably received, but it did not gain for the composer the recognition he deserved. As for the two preceding acts which make up La Prise de Troie, Berlioz was destined never to hear them. They were first played in concert in 1879, ten years after his death, and La Prise de Troie had its French stage premiere in Nice in 1891.

The five acts of Les Troyens were first produced together in Karlsruhe in 1890 where it was sung in German. It was not until 1921 that the Paris Opéra staged the work, though in a condensed version, and it was last revived there in 1961.

The British premiere took place in Glasgow in 1935; an almost complete version was used for the Covent Garden premiere in 1957; and Scottish Opera sang the first complete performance earlier this year [1969]. All three of these productions used Dent’s English translation. Now Covent Garden has combined a unique “first” with a centenary celebration and it is possible to feel that we have made amends to Berlioz for the neglect he suffered in his own country.

The performance is conducted by Colin Davis, who will be taking over as musical director of the Royal Opera in 1971, and who has already established his sympathy for and understanding of Berlioz’ music. It is produced by Minos Volanakis and designed by Nicholas Georgiadis—both Greeks. The former is a newcomer to opera production though familiar as a stage director; the latter designed last season’s Aïda at Covent Garden. They have worked together previously on several occasions.

In their visual approach to this opera, the producer and designer have emphasized the contrast between the two parts of the work, the one set in Troy, the other in Carthage. In doing so they have followed Berlioz’ lead; his view of Troy is essentially classical, but with the change in milieu comes a change of musical style and the Carthage episodes are treated romantically. Troy is conceived on solid, enclosed, and sombre lines. The atmosphere there is heavy with foreboding, the sky is dark, almost uniformly black. The air of Carthage is rarer, and Dido’s city is bathed in golden light; there all is warmth, elegance, and splendour.

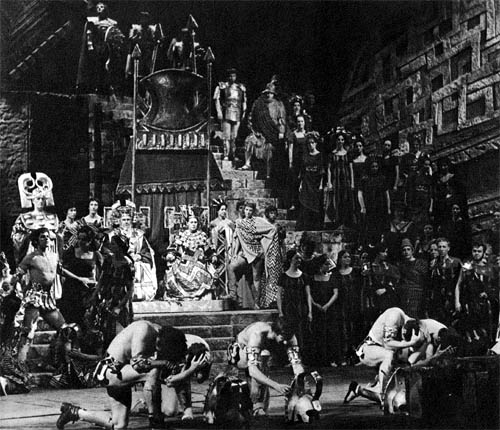

Mr Volanakis has avoided the danger of over producing this monumental work and for the most part handles the large forces required flexibly. There are 155 persons in the cast, including 20 principal singers and 30 dancers, but he uses no extras. The idea is to avoid having individuals standing around the stage looking as though they have no part in what is going on. Singers and dancers mingle together in the crowds and remain on stage throughout these scenes. Instead of having the ballet coming on to do their dance and then filing off again they are already there as part of the people rejoicing in the streets of Troy at the Greeks’ departure and their dances emerge naturally from the surging movements of the crowds.

Throughout the opera there are scenes which the composer conceived on a grandiose scale and which the producer has interpreted with real insight into the dramatic requirements of the score: the Trojans’ celebration of their supposed victory over the Greeks; the entry of the wooden horse (only its legs are visible); the lament of the bereaved Trojan women; and the festival scene in Carthage. But more significant are the passages in which Berlioz shows us his heroes in close-up, focussing attention on their personal destinies.

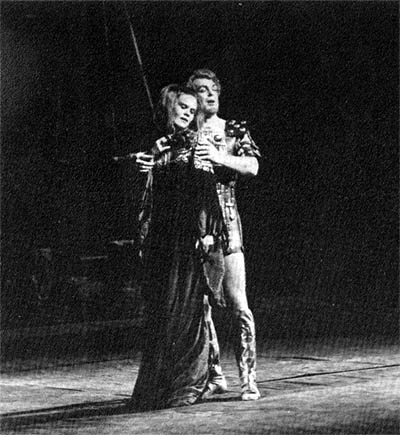

The whole of the Trojan section is dominated by Cassandra, the prophetess whose warnings go unheeded. Anja Silja portrays her arrestingly. She sings the part with tragic intensity, though the words she pronounces are indistinct, and is mistress of the style of acting which the role demands. Dido, Queen of Carthage, is a noble figure, slightly underplayed by Josephine Veasey in the earlier scenes but deeply moving in her distress when she is deserted by Aeneas, and sung with intelligence and sensibility.

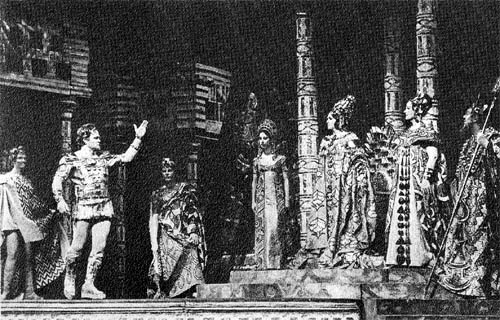

Jon Vickers sounded perfectly at ease in Aeneas’ heroic passages when he produced some vividly expressive singing, but his softer tones became muffled and uncertain, rather spoiling the effect of the beautiful love duet Nuit d’ivresse. It was nevertheless a performance which matched the scale of the opera.

There was excellent support from the chorus though diction was not their strong point, and in smaller roles mention must be made of Heather Begg’s Anna, Dennis Wicks’ Ghost of Hector, Ian Partridge’s Iopas, and Ryland Davies’ Hylas.

But the weight of this vast and breathtaking edifice was borne by Colin Davis who coaxed some rich and thrilling sounds from the Royal Opera orchestra, while maintaining a finely calculated balance. In his hands the music glowed into triumphant life and defied incomprehension.

The one disappointment of the evening was the scenic interpretation of the Royal Hunt and Storm music, which was danced by nebulous figures behind a painted gauze, but could any choreography match the mental pictures conjured up by such music?

Act I, scene 2: In front of the Citadel, the Trojans celebrate their

deliverance from the Greeks with a hymn of thanksgiving.

Act I, scene 1: Anja Silja as Cassandra and Peter Glossop as Chorebus.

Act III: Aeneas (Jon Vickers) and his followers arrive in Cartage

Act III: Heather Begg as Anna and Josephine Veasey as Dido

![]()

* This article has been scanned from a

contemporary copy of The Illustrated London News, 27 September

1969, in our collection. We have preserved the author’s original spelling,

punctuation, and syntax. We have not been able to contact the author of the article

or the editor of The Illustrated London News, which has ceased publication.![]()

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 15 July 2011.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Contributions Originales

Retour à la page Contributions Originales

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil