![]()

|

|

|

|

This page has been created to provide a forum for people from around the world to share and exchange their experience and encounters with Berlioz’s music. You are invited to contribute to this page if you would like to share your feelings about and views on Berlioz and his music. Please email us your contribution; it will appear here under your own name. There is also a counterpart to this page in French, Berlioz, sa musique et vous.

We are most grateful to John Winterbottom whose account of his personal experience with Berlioz’s music was the inspiration behind this page. He subsequently responded warmly to our invitation to make the first contribution to the page.

Copyright notice: Contributions published on this page are the intellectual property of their respective authors and are subject to UK and International Copyright Laws. Their use/reproduction without the authors’ explicit permission is illegal.

Berlioz! What is it about this fiery little French gentleman of a bygone century that feels so fresh and relevant to me? He is alive! That’s a phrase I often find myself repeating. His personality feels too bold and bright to be confined to the past, to the grave, to the chilly sterility of marble busts in quiet galleries. I half-expect to stumble upon his youthful self in the street carrying some meager bread and fruit under his arm, his roommate a few paces ahead pretending not to know who he is; or perhaps to see his older self seated in the shadows of a university auditorium, head in hand, listening in pensive, impenetrable contemplation to a student performance. He is vividly real to me, and history is more real to me because of him. Two hundred years ago is really just a breath or two away, after all. Reading these testimonies, I am comforted to know there are people who understand. I wish I could meet you all. For now, it is time to make my contribution to these testimonials.

I first met Berlioz in the basement of an old church. I live in the rural American Midwest, a few miles from a small town whose only real claim to fame is its university. That university’s only real claim to fame is its engineering department. Yet there I was, a senior in high school, taking a dual credit course on campus - and not in the engineering department, but in the modest, fledgling, much-neglected music department, which at the time was housed, yes, in a church basement. The sparkling light of that music department was the professor who taught that music history course. He was a conductor, a bassoonist, and a lover of the romantic and the macabre, so I suppose it was only natural that he had a special fondness for a certain Hector Berlioz. In fact, he began to mention Berlioz long before our study reached the Romantic period. He couldn’t seem to contain his enthusiasm for the man. As he was one of those particularly wonderful teachers whose love of his subject is contagious, he soon caused me to become curious about Berlioz myself. He recommended reading the Memoirs - probably not expecting a wide-eyed eighteen-year-old high school girl to follow through on the suggestion, but I did. Let me tell you, I was hooked from the first paragraph. “I came into the world quite normally, unheralded by any of the portents in use in poetic times to announce the arrival of those destined for glory. Can it be that our age is lacking in poetry?” Yes, I thought with a laugh; yes, what an unpoetic world! His voice was instantly captivating - so frank, emotional, humorous. Even with limited exposure to the music, I was sold on the man immediately.

The music stole my heart soon enough. Before long I encountered in class the glories of Symphonie fantastique, via my professor’s recordings and his ecstatic commentary. I’ll never forget his delightfully sinister cackling in the wake of the guillotine CHOP! and the plink-plunk of the rolling head at the end of March au supplice. It didn’t take me long to obtain a recording and a score of the Symphonie for my own personal collection. In addition, that class, that professor, and Berlioz himself, all became key factors in my ultimate college decision. I decided I wanted to major in music (vocal performance), and I chose to stay on at that university, so that I could keep learning from that particular instructor. Despite the modesty of the music department there - I know that my education was in many ways sub-par due to the lack of a well-ebstablished program - I am forever indebted to those years for officially forming me as a musician and a music lover. I actually became the first music major in the history of that school. My sister, a year behind me, became the second. A year after she graduated, the administration canceled the music major due to lack of interest, but we had made our little bit of history. We are special now, true rarities. And in a way, it’s because of Berlioz. To honor his role in my education, I insisted on featuring a “Berlioz suite” in my senior recital: I sang three selections from Les nuits d’eté (Villanelle, Absence, L’île inconnue).

“Just because of Berlioz” was, for a while, a catchphrase among my family members. In those early days of getting to know him, many of my actions and interests (a sudden passion for French culture, or for roaming the countryside inexplicably sobbing over God knows what, etc.) seemed to stem directly from my Berliozian obsession. My decisions made sense “just because of Berlioz.” I couldn’t help it - I felt I had found a friend. Berlioz put into music as well as words feelings I had thought no one experienced but me. His descriptions in the Memoirs of surreal emotional states, of the way music or nature affected his spirit - some of these discoveries made eighteen-year-old me jump with a gasp of recognition and elation. I wrote down some of his quotes in a notebook and memorized them. A favorite was, “During these crises one has no thought of death; the very notion of suicide is intolerable. Far from desiring death you yearn for life; you long to live it with a thousand times greater energy. It is a prodigious capacity for happiness, which grows exasperated for want of use and which can be satisfied only by immense, all-consuming delights equal to the superabundance of sensibility you feel endowed with.” Berlioz! He’s the best.

Dreary old adulthood and the world of work have occasionally threatened to sap me of the joy and exuberance that Berlioz once brought me. I have not always worked in music, and even working in music has not always been enjoyable. Drudgery! So much of life, and so many of the people I meet, seem to be devoid of what Berlioz calls “true feeling.” Still, I pursue that elusive stella montis. I will never give up on it. More recently, my love for Berlioz has returned with a passion. For weeks now I have barely been able to sleep - I would rather be listening to his music, reading his writings, exploring anything I can find about him online (this website has been a real revelation - thank you a thousand times to the good people behind these pages!), and of course, planning in great detail an imaginary pilgrimage to France, to see the museum at his birthplace in La Côte, his grave in Montmartre, his Parisian haunts. If I can ever find someone to go with me as a bodyguard and guide, this pilgrimage will no longer be imaginary! I am grateful to God for bringing this endearing little nonbeliever to my attention - this small person whose soul reverberated with the vastness of the spheres, whose glorious music speaks to the universe of immortal wonder trapped inside his mortal shell. Thank you, mon Cher Berlioz, for not bottling it up, for never giving in, for fiercely and bravely and so tenderly and vulnerably sharing your bright spirit with our dark world. Two hundred years on, my life is immensely more beautiful... because of you!

With love,

Elyse Buehrer

Indiana, United States

12 December 2022

It was probably some 55 years ago [in 1962] that I first heard the music of Berlioz, who was then a largely unknown, rather recherché composer! Brought up musically on the great Austro-Germans and the Russians, I would spend long evenings in Cheam, Surrey, where I then lived, at the house of a mélomane friend who had a vast collection of classical LPs and a great knowledge of music which he was willing to impart to a keen amateur. One day my musical friend put on the most quirky, whimsical, witty, lopsided piece of music I had ever heard – an utterly original and bizarre piece of orchestral wizardry. Yes, it was the Menuet des Follets (Minuet of the Will-o’-the Wisps) from La Damnation de Faust, and it bowled me over completely.

Needless to say I immediately adopted the minuet as my own personal ‘theme tune’; with a surname like Follett. (On the paternal side my family is of Anglo-Norman extraction, we came over with William the Conqueror in 1066). I had no choice, we shared the same name and I was something of a Méphistophélès sympathiser anyway – immediate empathy! I was at the time studying at King’s College, London for a B.A. Honours degree in French, and very Francophile; so it all fitted perfectly into place!

Before the great Berlioz revival of the latter part of the last century got underway, I had to make do with bleeding chunks only from “Faust” on records, but I still remember in particular fine performances of the Follets, Ballet des Sylphes and Marche hongroise by the likes of Igor Markevitch, André Cluytens and Charles Munch. Since this Follett’s first encounter with the Follets it has been a lifelong case of “Encore, encore et pour toujours”, as Lélio himself put it, as regards my devotion to Berlioz’s music and writings.

Bonne nuit, bonne nuit!

…Chut! Disparaissez!

(Les follets s’abîment)

I sang in the chorus of La Damnation de Faust in the staged production in Lyon in 1983 under Serge Baudo.

In Auerbach’s Cellar, close behind Ruggero Raimondi’s Méphistophélès, I fell hopelessly in love with Berlioz. At last, a free spirit with genuine, natural humour and wit!

I am a guitarist/composer. Since 1983 HB has accompanied me every inch of the way. I wrote music for a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream last year and the HB of Les Nuits d’été was my Shakespearean mentor – who better?

HB is also “family”. I am descended from the United Irish Emmets in Ireland. HB was born in the year of Robert Emmet’s death and I have read that HB thought (influence of Moore and Harriet perhaps?) that he was Robert’s reincarnation.

I agree with Richard Wagner that La Scène d’Amour is a masterpiece. No one in music’s high art has ever described love making better than HB, before or since.

I love to deconstruct appropriate songs back to imagined guitar “originals”. I was honoured to be invited to sing and play Méphistophélès’s Devant La Maison at a festival some years ago to a simple guitar accompaniment of my own. More recently I arranged Ô blonde Cérès for a tenor to sing to my guitar arrangement. I recommend this to all guitarists out there.

I believe that the guitar is major part of the key to understanding HB’s unique magic - he himself arranged his beloved Glück to sing to his own accompaniment - and also the key to understanding the blank incomprehension of German piano-based composers of his own time and since.

Let me end with a poultry metaphor: if Wagner tried to put all his hens into a universal battery farm, caged in by leitmotifs and endless appoggiaturas, Berlioz’s hens were free range and all the healthier for it!

Michael Sproule

Guernsey

Two of the world’s great mythologies inspired some of the greatest works of Berlioz : Christianity, which spawned the Requiem, the Te Deum and L’Enfance du Christ, and Roman Mythology, resulting in the immense epic, Les Troyens. We may add a third Berliozian obsession : Shakespeare, whom Berlioz regarded as a god, hence we have the Romeo and Juliet Symphony.

The important distinction, regarding Christianity, is that Berlioz, as a Catholic child, actually believed in the Christian myth, which in later life, was shattered by exposure to scientific rational thought.

L’Enfance du Christ is, in a sense, a requiem for his lost childhood Christian faith. His actual Requiem is the work of a devout agnostic revelling in the drama of the ancient Latin text, but in much of this work he expresses a sort of eerie and morbid quiescence – is he, again, expressing a loss of faith?

L’Enfance du Christ is a very moving work, where the violence of Herod’s infanticide, in Part One, contrasts vividly with the ethereal and tranquil depiction of Joseph and Mary’s flight into Egypt, in Parts Two and Three, the remainder of the work.

A strange transformation in musical style takes place, when an antique overture ushers in the final two sections of this musical triptych – it is as if a stained glass pictorial image, depicting the trials and tribulations of Joseph and Mary, is somehow magically translated into music of incredible sublimity.

The closing Mystic Chorus would be a profoundly religious piece, if it were not for the fact of Berlioz’s agnosticism! But it is profound, it is sublime, and it stirs some kind of primordial desire for the religious experience.

L’Enfance du Christ is indeed Berlioz’s requiem for lost faith.

Haydn Greenway, 2014.

Just looking at your site again and in particular the various memories of people getting to know HB’s music I was put in mind of something rather fantastic which I felt might be of some interest to you, whilst thinking about my Berlioz experiences: Roman Carnival as a teenager, Cellini at Covent Garden in 1976; Harold in Italy in 1981 under de Burgos in Basle – my few Berlioz Gramophone Records and this:

It was – I am not sure of the year – probably the early 1990s, and there was a strike of (I think) all the orchestras at the time (July) of the commencement of the Promenade Concerts in London’s Royal Albert Hall. A week or so passed and eventually to everyone’s relief amid rising annoyance the strike was finally settled. The earlier concerts were gone – written off – but the first work of the now delayed start of the Proms was the Symphonie Fantastique (the BBCSO – relieved to be performing again – I think). Was there ever a more appropriate start to a delayed Proms than that! – it was as if – especially in the last two movements – Berlioz was commenting on the frustrations caused by the strike. The Prommers were ecstatic at the end, as well they might be – I heard it on the radio but the atmosphere was unmistakable. I find it difficult to find the words to adequately describe the experience.

In the autumn of 1955 I joined my school orchestra. The centrepiece of our next concert was Bizet’s Arlésienne Suite. For someone familiar only with the traditional Austro-German orchestral repertoire and modestly so at that, Bizet was a delicious surprise: transparent textures, sparkling instrumentation, urgent rhythms and a clarity… where did it come from? After the concert, my music-loving mother told me that if I liked Bizet so much, I would love Berlioz. I should try his Symphonie Fantastique. So I borrowed the 1953 LP by Markevich and the Berlin Philharmonic from the school record library.

We could only listen to records at school on the house’s cheap early 1950s radiogram, with its worn needle, plummy bass and thin distorted treble, at inconvenient times in the bleak, unheated recreation room of the sanatorium. To make matters worse, this LP was dusty, crackly and scratched, like so many library records. Nonetheless, I was bewitched as soon as the Idée fixe appeared. What on earth was this wayward, hesitating, mesmerising tune with its erratic accompaniment? The sleeve notes were of no use as they had been largely torn away… the Scène Au Bal at least was familiar ground; but what were harps doing in a “symphony”? And as for the last two movements… how could anyone write music like this only a few years after Beethoven’s death?

If I wished to get to grips with what Berlioz was up to, my mother suggested I should read his memoirs. He was, she said, a brilliant author and had written graphically about the extraordinary circumstances of the composition and its early performances. I doubted his writing could match his music. But I quickly found myself swept up by his passions, his enemies, his bêtes noires and his prose. At the same time, to a romantic teenager at a boys-only school his accounts of Harriet and Estelle glowed like an illuminated manuscript.

But then a surprise: l’Enfance du Christ, in a Christmas broadcast (possibly by Adrian Boult and BBC forces). Not at all what I had expected. One or two lollipops, but otherwise so archaic and subdued. What had become of the scintillating young Berlioz? My interest waned. And then, one day, I found a second-hand Decca 78 rpm (short play, shellac) of the Carnaval Romain played by the LPO under Victor de Sabata, probably recorded shortly after the war. It was in good condition, and sounded very well on the family’s pre-war EMG Handmade Gramophone. This marvellous anachronism reproduced sound acoustically via a triangular Burmese cane needle held directly against a metal diaphragm at the end of an immense papier mâché horn. Once again Berlioz worked his magic, and my enthusiasm was rekindled, at a time when by chance the Covent Garden Trojans and the activities of Sir T. Beecham were provoking a growing flow of critical interest and public comment.

Back I went to my reading, this time determined to spread the word. So in 1959, in the teeth of friendly puzzlement and scepticism, I delivered a half hour talk on Berlioz to fellow 6th-formers in the school essay society, without the support of any musical examples. Thanks to Berlioz himself and the brilliant passages I was able to quote from his memoirs, the talk intrigued and interested even the most musically philistine of my contemporaries… and 53 years later I continue to spread the good news.

I am just a newcomer to the classical music world. I ‘met’ Hector Berlioz at one of my last exams at university, and I just knew nothing about music or about him. I could not ignore such a great personality.

The first thing our professor said about him was, almost literally: this man is mad. That awful statement made me think: I am going to like him. Then he started with a little resumé of Berlioz’s biography: the escapade from Rome to Paris [in 1831], the Machiavellian plan to kill three people and himself, all that kind of stories... which were far from making me think badly about him! And we listened to the Symphonie fantastique... That was better than a movie: I could exactly imagine what Berlioz was thinking, and at the same time I was free to see his dreams in my personal way. So he guided me, and that satisfied me.

I know very little about the great operas of Berlioz, I cannot say more than that I admire him, and that I have read almost 10 different biographies of him since my first lesson about his music. I am not a musician, I can only read music... like a 3 year old child... But I think I am an artist, and I feel very close to everything I read about Berlioz. So my only way to let the world know of my passion is by drawing it.

I would like to explain better the matter of the guide... not only in music, but in a more general way. He was not only a musician, of course... He was a story-teller, a great and learned man, a bright and living spirit, full of energy... he had no frontiers. I adopted him as a point of reference not only in music but in history, and, because I am always out of the world, in how to face life; I know perfectly how many differences in culture and in time divide us (not to mention the fact that I am a girl...), but I try to have him as an example, to work hard, to follow dreams and not to be let down by accidents... even if they happen to be huge... I also know that a man with a great and brazen personality like him could not be easy to deal with... but I do not expect this of an artist. Even if he is far in time and in place, I sometimes feel I know him.

For his time, he was too much. But we do not have to forget how hard education was in that century: young people like him had every reason to run away from their world, too full of rules to follow, conventions, social obligations... Berlioz had never been rude, even when speaking about great passions or orgy scenes. Never hypocritical, always sincere. And always faultless. That is how I imagined him, reading about him and listening to his music.

I invented a lot of stories, I mixed up centuries and names, but he himself is clearly recognisable. I portrayed him as some might imagine him: with black hair and dark eyes, circled in black and with shadows under them (proof of the fact he never shuns hard reflections and work). The Mediterranean soul, an ideal representation (I did the same with Mendelssohn, but reversing colours and showing him as a ‘boy of light’). There is no pretence of reality, just my clumsy way of saying: That is it, I like it!

I thought I was making it up when I made drawings about the great friendship between Berlioz and Mendelssohn: I was fascinated by the great difference of their personalities, and I wondered how one could put them together; then I discovered that it was true. Berlioz and Mendelssohn did meet in Rome in 1831 then again in Leipzig in 1843 when they exchanged their batons as conductors.

I know only the Symphonie fantastique and the titles of his other masterpieces. It is the first time, after ages, that a person who really lived interests me so much, so this is my best way of showing it.

With my first sketches, while I was studying for that exam, I had a dream of Berlioz as a pirate... so... But in the last ones I tried to follow a different path, and my character changed, being closer to the real one. He is always himself, however.

It is a work I am proud of, though I am hardly even a beginner in this kind of world.

Marcella Acone

Italy

__________________

See also on this site Berlioz sketches by Marcella Acone.

A prophet is not without honour, save in his own country and in his own house.

St Luke 11 57

This backwards glance through memories of a lifetime’s devotion to the life and music of Hector Berlioz was prompted by the grotesque English National Opera production of The Trojans in October 2004 along with the discovery of this exceptional website, enabling me to give birth to my thoughts. Some is nostalgia of little consequence but I hope that it will be of interest to all enthusiasts.

Born in London in 1934, I was put to the piano but never found any particular pleasure in music, until something strange happened at the end of 1949. In those post-war days, the BBC broadcast only three programmes, the Home Service, the Light Programme and the Third Programme, this last being considered very esoteric. We were mainly Home Service (now Radio 4) listeners and the wireless was frequently on. Almost every day and some evenings an orchestral concert was broadcast, so unconsciously I absorbed lots of good music.

In the school holidays, Haydn’s 104th was played on the 29th December and I must have paid some attention to it as in the night I had a kind of numinous experience, waking and sitting up in bed and ‘hearing’ some of it. (Bars 20-23, 1st movement as I learned later). It might have passed for just another soon-forgotten dream, but surprisingly (for those days), the symphony was broadcast again the very next day on the Light Programme and I made a point of hearing it. Interest aroused, I became totally absorbed in classical music, listening to everything I could, making lists of works heard and when, and starting to read biographies. School work suffered, so obsessive it all became.

We were not so bombarded then as now, with so many different kinds of music / noise so some of it was very hard to get used to, such as Delius and Sibelius. The first time I heard a Martinu symphony, I couldn’t believe the sounds that reached my ears as they seemed so totally extreme and crazy. Musically immature, the Romantics did not always make for easy listening either. Brahms seemed particularly dense and impenetrable, but I persevered.

An unexpected musical experience was our class being taken from school one morning to the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden without any warning, for a performance of Barbarina, the reduced version of The Marriage of Figaro. In that still grey, post-war world it was something that readily imprinted itself vividly on my memory. I’m pretty sure that Geraint Evans was one of the singers. Around 1990 when I went there with my wife for a dress rehearsal of the full opera I sat in the same seat, or one very near it.

Back to around 1950. One evening, on the same radio, standing in the corner of same room as it was when the Neville Chamberlain gave his memorable speech of the declaration of war against Nazi Germany some ten years or so earlier, I heard the Roman Carnival overture. It attracted me as it seemed unusual but disjointed, and a little sad. But it also intrigued so much I had to investigate it further along with the life of its composer. Berlioz was beckoning.

Was that experience the seed which fell on ground partly prepared by being hopelessly in love-at-first-sight from the age of about 12 and from the influence of my eccentric church choirmaster Albert Frederick Bolton? Whatever, heady Berlioz and an impressionable mind meant the start of a lifelong love-affair and an allegiance which has never faded.

My first Master Musicians biography, Handel, was bought in early 1950, then Haydn and Mozart. J H Elliot’s book on Berlioz in the same series was a Christmas present from my girlfriend – but the inscription was cut out following heartbreak.

I still have a 1951 Christmas present, a first edition of Barzun’s Berlioz and the Romantic Century and writing these notes has prompted me into reading it again.

I was fortunate that my school was near a library which had a record lending department and heaps of scores. At that time, although the library didn’t stock all of them, it might have been possible to carry under one arm all the then current Berlioz shellac 78s recordings. I probably started with the Fantastique as I wanted a preliminary hearing before a performance at the Royal Albert Hall. I sat in the arena one afternoon and heard Victor de Sabata’s rendering. The Waltz had been easily assimilated from the discs but the rest really needed more time to mature in the mind before the concert, so I was insufficiently prepared and it was a bit disappointing. Being so very earnest then, I didn’t think much of a violinist who I believe was the late Granville Delmé Jones sharing a private joke with another fiddler, grinning at each other during a tremolo passage of the Scène aux Champs. And in my ignorance, I was disappointed at finding that real bells were not used.

However the most important revelation was to be the Serge Koussevitzky Harold en Italie which became totally captivating. Making sense of it was aided by the Eulenberg miniature score and understanding gradually emerged out of the fine chromatic fugal Introduction. The violist was William Primrose. These discs (recorded in 1944) were accompanied by as much reading as was possible mainly from Elliot’s biography. Its overall negative critical comment allied to Berlioz’s rather sad life made it a dispiriting read. Although it was republished in 1969, in a new Preface the author said he saw no reason to revise his opinions of more than thirty years previously, which had repeatedly criticised Berlioz for ‘unevenness’, ‘lack of staying power [and] musical maturity’.

My exasperated father rented for a few pence a week, an extension speaker from Radio Rentals, (yes, it sounds odd but that was how most people acquired radio apparatus then). I could now have my music on in the kitchen relayed from our small living room’s newly acquired Ferguson automatic radiogram and the rest of the family got some peace. We argued much about loudness and I was totally unreasonable of course. Much later, Dad vicariously got his revenge by my being tormented by the next generation; the illiterate heavy metal row my son played.

After replacing the radiogram’s automatic turntable with the cheapest Decca 33? rpm model, (another row with Dad!), I saved up the money to buy an unbreakable LP, issued 1952 of Roméo et Juliette excerpts and the Royal Hunt and Storm. The Paris Conservatoire Orchestra under Charles Munch played on this Decca disc and the French horns had that silky sound not heard so often nowadays.

The seemingly meaningless meandering violins of the opening of Roméo seul made sense as a typical fine Berliozian melody once it had matured in my mind. The later purchase of the HMV complete Munch Roméo was revelatory. The days of puzzling over the miniature score wondering what the unheard music sounded like were over. The spiritual love scene, the agonies of the tomb scene! And how brilliantly Berlioz captured the gathering of the anxious and excitable Montagues and Capulets and their retinues at the end of the work.

By the way, full price 12" LPs cost nearly £2.00 each – a huge chunk from my starting salary of £3.12 0 (£3.60) per week. Decca, (who dropped the term unbreakable in favour of flexible), had been the first UK company to issue LPs whereupon HMV archly declared that they saw no future for the format – but they had to relent some fourteen months later.

Among the first clutch of Decca LPs was a work almost unknown at the time, Les Nuits d’été sung by Suzanne Danco with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra under Thor Johnson. Despite this being a cheaper 10" disc, price had put it beyond reach.

This was before I left home to go into the Royal Air Force, serving mostly in the Egyptian Canal Zone where I bought (purchase tax free!) Beecham’s Te Deum and Scherchen’s Les Troyens à Carthage. I managed to hear the Te Deum there once only – a wall of sound which later needed repeated hearings to appreciate. Alas, the parcel sent back to the UK containing these discs was opened by Customs and they scratched the delicate LP surfaces.

Excepting Sir Walford Davies’ March Past, oft heard on the parade ground, the RAF was a musical desert so these works were much played during the holiday I took before going back to office life.

Berlioz could not have known Masefield’s Where does the uttered Music go? but all the music on these discs is deeply, deeply embedded in the walls of my London home – and much more in all the other houses since lived in. I don’t think it’s solely because she was my first Dido that I still regard Arda Mandikian as the finest. for her passionate, Latinate approach to the role. Like most of the other principals who may not have the finest of voices, she has a rare clarity of delivery which I value over richness of tone. Also, I adore French nasal tone.

In those days when there were few works performed, and there was a tendency to see Berliozians as a vocal minority of irrational and prejudiced zealots whose hero could do no wrong, it was a rare privilege that my second live Berlioz event was the Carl Rosa Opera’s Benvenuto Cellini at the New Wimbledon Theatre. A Society member guided me through the work and I think I met Ron Bernheim there and noticed in the audience a very short comedy film actor who I believe was Robertson Hare.

What a joy to have been at Covent Garden on the 14th June 1957 for The Trojans. The conductor was Raphael Kubelik with Jon Vickers and Amy Shuard (Cassandra), Blanche Thebom (Dido) and Lauris Elms (Anna). A clear recollection is of Thebom circling the funeral pyre with her waist-length auburn hair; but my treasured programme, (now in the Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin archive), shows Elms as Dido and Thebom as her sister, Anna. I took the opportunity to e-mail Joan Carlyle who sang Ascanius and she confirms that Thebom did indeed sing Dido, and Elms her sister Anna. Closer examination of the programme shows that Dido and Anna’s details had been reversed. Joan Carlyle also mentioned Dido’s ‘ENORMOUS diamond ring’ which as Ascanius she would have playfully removed just before the Act 4 quintet.

A treasured memory is of a devoted operagoer friend from our local gramophone society who came up to me after the performance. Enraptured, referring specially to the love duet he said, “Now I know what you mean about Berlioz!”

Rhydderch Davies, who went on to greater things, was the second soldier. It was very sad to hear him relate in a 2004 radio broadcast that he lost his voice and had to work as a taxi driver.

The purple-covered catalogue of the magnificent 1969 Centenary Exhibition Berlioz and the Romantic Imagination at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London is a richly illustrated mine of information. To have seen the score of the Te Deum loaned from Russia and so many pictures, letters, prints and memorabilia and so on all in one place was a special privilege. And how touching was a corner exhibit where one stepped up and stood in front of a small semicircular velvet padded barrier, (as if at the front of a dress circle), and peered down quite a long way it seemed, at a small stage on which a tiny Ophelia, dressed in white appeared and re-appeared and maybe spoke a few words.

Berlioz truly had arrived – in Britain at least.

This was the same year that I was with David Suffolk my closest friend over the past 54 years, a very knowledgeable Berliozian, when we heard the Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale and the Te Deum in St Paul’s Cathedral, sitting well back in the nave. A better place would have been the choir stalls where I sang for several years at the annual December Church Army service when in a church choir. Family priorities were probably why we were not together when a few days later David went to hear the Requiem at the same place.

We’d become pen pals through the Berlioz Society when I was in Egypt after I took up David’s offer to buy photographs of Berlioz which he was printing. (He now tells me he copied them from Barzun. Tut, tut!).

It is fair to say that I’ve ‘kept the faith’ less consistently than David, but my ardour has been no less.

I missed being a founder member of the Society by a month or two. The roneoed pages of the Bulletins were read and re-read, all the time learning more. The American Berlioz Society started a little later and their output arrived as well. These documents would be of great interest now but did not survive one of my house moves.

Berlioz was served well in 1969 as the centenary of his death coincided with the City of London Festival. Despite tickets being hard to obtain, (and very expensive as also was the 100 mile journey to London), I phoned Covent Garden to try to get to Benvenuto Cellini under John Pritchard and was lucky. But shortly afterwards the box office phoned back and said there had been a mistake and the booking was cancelled. The spirit in me of Berlioz militant was aroused. I reminded them of the law of contract, (of which I knew very little), and somehow the booking could be honoured after all. Quite why I sat among about a dozen empty seats I know not. Immense care had been taken to restore to this production some of the cuts and revisions the work suffered from in the composer’s lifetime.

Opinion about Berlioz has changed greatly over the past hundred years. For example, in The Story of Opera (E Markham Lee, 1909), he is curtly dismissed:-

Passing over that eccentric genius, Hector Berlioz who made a few bids for popularity in operatic composition, with remarkable lack of success, we must notice the brilliant Auber… .’

That comment is partly counterbalanced by:-

An eccentric genius among musicians. Wrote operas such at Les Troyens and Benvenuto Cellini which contain fine music, but which have never pleased the public and remain practically unperformed.

Cellini had been unjustly neglected, and it’s not hard to see why Berlioz was so deeply wounded by its rejection and treatment in France and England. With my wife I was at Covent Garden in 1972 for the Colin Davis Trojans. The production was traditional and sumptuous with a brilliant solution giving credibility to the Trojan horse whose legs only could be seen, thus implying its huge size. Cassandra with the chorus of Trojan Women had seemed a dull and lengthy tuneless episode in the Kubelik production, but as always Berlioz knew best and familiarity with the music and its being played at a decent speed has revealed superb melodies of which I never tire.

The Dido and Aeneas love duet ended most beautifully with the couple, their voices fading and echoing as they slowly walked hand in hand towards the back of the stage.

The mezzo-soprano Marie Collier who was the head of the Trojan women in the earlier production had originally been chosen to sing Dido, but at a party held to celebrate the forthcoming event, she fell from a window in Leicester Square, London, tragically dying from her injuries.

The production was everything I believe Berlioz would have wanted; i.e. the staging was founded on his directions. His vision of Virgil’s Carthage was a Romantic one from paintings by artists such as Turner, Guérin and Delacroix and being immersed in this tradition I cannot come to terms with the nonsensical 2004 smouldering aircraft wing, jump suits and table dancing. There are several tart quotes from Berlioz’s writings which I believe he’d hurl at the perpetrators of such travesties.

It has taken many years before being able to enjoy Aeneas’s Inutile regrets to the full. I’ve never heard the Georges Thill 78, described in The Record Guide (Desmond Shawe-Taylor and Edward Sackville-West) as ‘the loudest record ever made’. (I wonder where my first edition copy of this book is now, readily identifiable with my name written in it).

In 1990 I was alone at the London Coliseum for the colourful English National Opera production of Beatrice and Benedict. I don’t know the exact date, so the Beatrice could have been either Ann Murray or Ethna Robinson and as Benedict, Philip Langridge (Ann Murray’s husband), conducted by Mark Elder or Lionel Friend. David Suffolk was with me at the Royal Festival Hall in August(?) 1992 for the same work, with John Wells as a rather unfunny narrator.

David reminded me that on our annual jaunt to the Royal Albert Hall Proms we heard the Requiem on the 23 July 2000. The combined Orchestra of the Guildhall School of Music & Drama and the Paris Conservatoire were conducted by Colin Davis.

Again with David, at the Symphony Hall, Birmingham on the 6 January 2000 for a powerful and, as we were at the front of the stalls, at times an ear-splitting Requiem under Roger Norrington. How good to know that there were (and are), so many talented youngsters in the Youth Orchestra of Great Britain equal to the task of performing this work.

I self-published my family history in September 2000, heading the Preface with Berlioz’s words ‘I have lived my life with this race ... I know them so well that I feel they must have known me.’

Serendipity took a hand when I was transcribing for the Friends of The National Archives (formerly Friends of the Public Record Office). One project I contributed to entailed inputting from the large registers, written in beautiful copperplate, full descriptions of 250,000 copyrighted 19C photographs in the care of TNA.

COPY 1/405 folio 211

21 Jul 1891

Photograph of Celebrated musicians: Kriehuber [portraitist], Berlioz, Czerny,

Liszt and Ernst (Copy annexed)

Name and Place of Abode of Proprietor of Copyright. Joseph Percival Crawley, 140

Stephens Green, Dublin.

Name and Place of Abode of Author of Work: Joseph Percival Crawley, 140 Stephens

Green, Dublin

Kriehuber’s original print was dated 1846.

And now for a particularly pleasurable episode. My night school French tutor had urged a visit to Le Parc de Monceau, despite its being well away from the main Paris tourist areas. So, with my wife, during a short holiday we walked there very early one October morning and found it to be a place of much charm and beauty. It was made especially attractive by the morning mist swirling in the gentle breeze allowing brighter light to break through. Parisians were hurrying to work and a lady was feeding the birds. It was well worth all the walking.

It is a park of shady walks, leafy bowers, ponds, imitation natural springs, an Egyptian pyramid, a Dutch windmill and so on – everything that makes for complete informality. The famous Naumachie, a pond surrounded by a semi-circular colonnade of fluted Corinthian columns, partly broken, partly missing, is so overgrown with vines that it looks as though it has been standing there for centuries. Contrasted with the splendid formal Parisian gardens, there is absolutely no order here. The trees grow naturally, the walks curve around in the most unexpected manner, and everywhere remnants of broken Roman columns, archways, parts of ancient ruins, forgotten statuary.

So where is the Berlioz connection? A re-reading of Cairns Volume 2. Servitude and Greatness, provided a pleasant surprise on reaching p.718 which recounts Berlioz’s visits around 1864 to this very park, one of his favourite haunts where he liked to go very early enjoying it in the first light of dawn. In a letter to Pauline Viardot he wrote: -

I own a fine garden which costs me nothing, despite the two or three gardeners who are kept busy constantly tidying it and varying its adornments.

Some of the above detail about the park was cribbed from its website. I asked for the description to be expanded to refer to the above quotation. Within a day it was changed, not quite in the way I wanted, but at least our hero now gets a well-deserved mention.

Remarkable too, was that at about the same time the House of Commons was debating the vexed subject of Living Wills, I’d been reading Cairns Vol 2, p. 444 where Berlioz’s agnostic views on euthanasia are quoted from a letter to his sister Adèle, following the death of their sister Nancy.

Miscellaneous Berlioz connections and ephemera

At the 1969 London Exhibition, two commemorative ceramics ashtrays were on sale, one of them had Berlioz’s head on it.

Ci-gît une Rose que tous les rois vont jalouser (Here lies a rose that every king will envy), from the final verse of Le Spectre de la Rose were words that came to mind at the time of Princess Diana’s death. I wondered if they might make an appropriate epitaph, but as time passes they seem less and less appropriate.

It must be nearly 50 years ago that BBC televised a serial The Infamous John Friend, (Mrs R S Garnett, 1909), a tale woven into Napoleonic times. The late Barry Foster played a leading part. This turned out to be a mini festival of Berlioz excerpts. I can’t recall any apart from each episode being introduced by the opening bars of the 4th movement of Harold en Italie.

I was able to make a third visit to La Côte St André in 2005 to pay homage and tour the enlarged museum. When I was there about 5 years before, the assistante de conservation of the Museum, Madame Paris, coped with my schoolboy French and seemed impressed with my lifetime’s devotion to the man whose home she guarded, and she produced the Visitor’s book for me to sign. Alas, fine words failed me so my entry is rather feeble – made all the worse since many illustrious musicians have signed and commented.

A person born around the year of Berlioz’s death could have heard only a fraction of his output so I’m specially privileged by having heard almost all of it. But nothing can recapture those far-off days, (Gone alas like our youth, too soon), when so little of the music was accessible and one had to let the imagination take over from books. Only later came the joy of hearing the music itself. Today those circumstances would be difficult to encounter.

To my mind, there are two central enigmas surrounding Berlioz and his music. The first is the wonderment at how a youth from remote rural France could have arrived in Paris with comparatively little musical knowledge and in a few short years produce a symphony of such maturity. But this is the equivalent of pondering what Mozart or Schubert might have achieved had they lived to old age – and is rather pointless. The second is why Berlioz exerts such a hold on his admirers. His music can take a long time to work its way into the mind but even after repeated hearings it comes up fresh time after time, always with more to discover and enjoy. Like Christmas carols, the music never tarnishes. His life being inseparable from the music and so very interesting, has much to do with this endless fascination.

It is so very hard to choose my favourite Berlioz music. The four successive items, from Act 4 Scene 2 of Les Troyens, Iopas’s aria to the end of the love duet would be the last music I would hope to hear on this earth. If pressed to refine this choice it would be the quintet in which the shade of Berlioz’s beloved Gluck, which broods throughout much of the opera, is particularly evident.

My musical voyage of discovery, the journey of a lifetime, continued with performances in 2007 of La Damnation de Faust at Birmingham and Benvenuto Cellini at the Barbican is coming towards an end; but it is good to know that the music and reputation of this truly great and fascinating man is in good hands, in this country at least. Whatever part I’ve played is but a very tiny one of support, but I hope that it has helped to keep the torch aflame, to carry it forward and add lustre to the man, who in Elliot’s words, ‘remains himself, Hector Berlioz, the unique’.

Alan Merryweather

Cirencester, England

January 2005; March 2009 (Revised)

In my junior year of high school, I took advantage of my school’s music theory class. The first half of the year was dedicated to learning scales, basic keyboard skills, and the like. The second half was dedicated to music history – mainly studying composers. When the first day of our study of the Romantics finally came about, we were told about the life of a man named Berlioz, who had fallen madly in love etc. etc. As the music began (March to the Scaffold), I was instantly rooted to my seat. The brass fanfare was enough to make up my mind that this was by far the best composer I had yet heard. He remains so to this day, and will surely never be replaced.

In the first couple weeks after our introduction, I could not go a day without running across something related to the great man in my own life. The next day, Symphonie fantastique was played on the National Public Radio. The day after that I found a first edition of Barzun’s translation of the Evenings with the Orchestra. A couple of days later my friend pointed to a copy of Berlioz’s Memoirs right under my nose at an antique store. Cellini’s autobiography nearly jumped off a shelf at me at a second-hand bookstore around the same time. What were the chances?

In my senior year of high school, my show choir spent a weekend in New York City. We could choose whatever we wanted to do that Friday night. I wanted to see a musical, but, being a weekend in NY, they were all sold out. Then I discovered that Sir Colin Davis would be conducting the NY Philharmonic that night. I jumped at the chance, emailing the powers that be to see if I would be able to get the chance to meet him after the performance. I was told it would, but, unfortunately, it did not work out.

I discovered that Sir Colin would be conducting a Pure

Berlioz concert at the Barbican Centre in December of 2007. Adding to the

list of reasons for my wanting to go to London, I  blew all of my graduation money on the trip. Once again, I emailed the powers that be and was told that I would have no problem talking with him backstage after the concert. Before the concert, I had a wonderful dinner and chat with the incredible creators of this site.

blew all of my graduation money on the trip. Once again, I emailed the powers that be and was told that I would have no problem talking with him backstage after the concert. Before the concert, I had a wonderful dinner and chat with the incredible creators of this site.

When the time finally came, I dodged the security guard (care of the principal second violinist) and made my way backstage where I was able to chat with Sir Colin. All-in-all, it was a perfect day, thanks to Hector!

Ashley Donaldson

(click on the photo to enlarge)

I discovered Berlioz, as a teenager, in 1969 – the significance of that centennial year was, then, unknown to me! The music was Symphonie Fantastique – a reel to reel tape, Otto Klemperer was the conductor – the Scène aux Champs was more Mahler than Berlioz, but the March was wonderfully heavy!

Having been brought up on the symphonies by Haydn, Beethoven and Brahms, my first experience of the Fantastique was one of incomprehension and a certain bewilderment. Then, after several listenings, the penny dropped! Those long sequences of lonely, sparsely accompanied notes became beautiful, extended melodies. This, I realised, was an overwhelming piece of musical drama – powerful and TRUE – a fusion of opposites. How can the elegant, if somewhat vulgar, waltz exist without the brutal and barbaric March to the Scaffold? I now recognise this fusion in all of Berlioz.

I next heard Harold in Italy, and this piece had an immediate impact. I love this symphony – and it is probably my favourite Berlioz piece. The evocation of colour and imagery, as in most of his music, is almost hallucinatory. Those weird viola arpeggios, played sul ponicello during the Pilgrim’s March are other-worldly, and the mellow ‘burnt Sienna’ sound of the viola, simply beautiful.

Another work, La Damnation de Faust, is positively psychedelic, where Faust’s positive experiences are perpetually annihilated by the Devil, in a blinding flash!

Les Troyens is classical opera, interpreting classical Virgil in glorious, if tragic, orchestral and choral Technicolour.

The Requiem is astronomically cosmic – the depths are blacker than black, the climaxes white hot! This evocation of visual imagery brings me to a very interesting episode in my Berliozian ‘trip’.

Soon after my discovery of Berlioz, I read his Memoirs – the man struck such a chord in me, that, in a sense, he became a ‘friend’ – I became fascinated by his life, his work, his appearance – his incredible facial physiognomy – I began drawing and painting pictures of Berlioz. When I was studying for my physics, chemistry and biology ‘A’-Levels, in 1970, my chosen extra-curricular subject was Art. One of my projects was clay sculptures of Berlioz. It was at this time that I read an article by the artist Michael Ayrton (1921-1975) in the ‘Great Musicians’ series of records – ‘Berlioz Part Three’. This record introduced me to the Benvenuto Cellini, Roman Carnival and Corsaire overtures and the Rêverie and Caprice for violin and orchestra. Michael Ayrton’s article was a revelation – it was entitled ‘He’s a Friend of Mine’ and he expressed his love and obsession with Berlioz in sculpture and painting, just like me! In my teenage naivety, I wrote him a letter, expressing my astonishment that a like-minded soul had found his expression of his love of Berlioz in Art! And to my utmost astonishment he replied (see letter). In the ‘Great Musicians’ article, Ayrton wrote, ‘[Berlioz] has an extraordinary capacity to evoke the quality of sight by musical sound’.

Recently, since I’ve joined the high-tech digital age, I’ve created, on my computer, montages of my paintings and sculptures, past and present, inspired by Berlioz. Of particular interest is my Harold in Italy montage, since it includes an image of one of the clay sculptures of Berlioz I made way back in 1970. Monir Tayeb has kindly posted this montage onto the Berlioz Website (Berlioz-Inspired Works of Art).

Actually, this particular montage is something of a family affair – the Paganini image is from a recent oil painting of mine, and the viola is a creation of my father – now 86 years old – an amateur violin, viola and cello maker. His favourite composer is Haydn – hence my name – and he was the one that bought me the Klemperer tape of Symphonie Fantastique, all those years ago!

Haydn Greenway

Our visit started much sooner than expected – as we approached Lyon from Grenoble airport I was already being tantalised by the signs for La Côte. Incredibly a roadside sign for the town came into view, a lovely picture of H. B. himself set against musical bars from one of his own scores. Despite my cries to stop so that I might photograph this, it proved impossible to do so, and I really hoped to do this another day.

On Thursday 5th April, a cool but sunny day, we returned to La Côte for our proper visit – and as we approached the town the prettier did the countryside seem to become. The area, close to the Rhône-Alpes, in this part has gently rolling, part-wooded hills with trees now coming into blossom.

Parking quite close to the 900-year old church where Hector Berlioz was baptised, we walked down into the town, making our way past a few chocolate shops, another famous product of La Côte. I thought I resisted that rather well, but I was focused on other things!

The museum itself was instantly recognisable to me, and it was with great anticipation and excitement that I walked through that door. We were greeted and issued with tickets and supplied with audio guides in English by two most charming French ladies whose English was as limited as was our French. Somehow we did manage to understand each other.

From then on, we had the museum to ourselves for what must have been three hours. What struck me first of all was the feeling of ‘family home’ it still retains. Beautifully laid-out patterned wooden floors abound throughout, also you step on what must be the original stone flags on the stairs, the staircase having a lovely wide aspect which gives the house itself a real sense of importance. Berlioz was indeed lucky to have been born into this household. The family’s background and the times in which they lived come to life as you journey through the exhibition.

Doctor Berlioz, a fascinating character himself, appears to have been largely self-taught, finally finishing his formal training and study for just a few months in Paris before gaining his title and returning home to his practice as a town doctor. How different it would be today!

The audio guide is rather splendid, perhaps one of the best and most informative that I have come across. Pictures, paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, letters – all were introduced and explained and we were left freely to soak up the atmosphere and examine whatever we wished.

A life-sized sculpture in a downstairs room took my breath away – I don’t think I have seen this one before, it shows a pensive looking Berlioz and commands the room even from a side wall.

Upstairs many exhibits are in cabinets with sliding drawers. Much of the contents are original items and left me literally gasping – there was the very familiar handwriting in reality in front of me – Berlioz was ‘alive’ in everything, you had only to close your eyes to imagine him popping his head round a door at any moment.

It was in Hector’s bedroom where I stood and gazed out over the garden imagining the young Hector and his sisters and brother going out to play. I turned and looked at the blue walls, when the thought came to me of Hector looking at those very same walls as I was now, and it was suddenly overwhelming. I’m not ashamed to say that I shed a few tears in that room. Apparently Ken, bless him, had been waiting for this! I don’t like to disappoint …

Upstairs I was also particularly taken with a large window blind covering the whole window – this was printed with a faint photographic image of Berlioz – an absolutely beautiful effect.

There are computerised terminals in one of the last upstairs rooms where extracts of some of Berlioz’s works could be chosen and played. Ken selected sections of Symphonie fantastique and what a wonderful way to hear it, in Berlioz’s own childhood home.

The last upstairs room is very sad. It focuses on Berlioz’s final years, including a silver grey curl of his hair and leads you inevitably to his death-mask. I found this incredibly hard to approach but when I did, I was struck with the profile of that much loved face. You can see very clearly that the many paintings and photographs we all know so well do in fact give a very true likeness. There is no mistaking that amazing profile. Nor in fact that amazing music which could not possibly have been written by any other composer.

In the auditorium downstairs, the last room before the exit, I gloried in the Te Deum, and the Grand Symphonie funèbre et triomphale. It seemed a fitting way to leave it with that wonderful music still resonating in the air….…

As we were leaving, Ken pointed out the busts for sale in the shop – we had seen so many throughout the house that I had stopped even registering them. As it was my birthday this was a timely and precious acquisition, and it now has pride of place in my front room.

What a fantastic visit – I loved the museum, so carefully and lovingly realised and exactly what I would have wanted for Berlioz myself. Tasteful, not over commercialised, in this Musée the French have done Berlioz proud. I came away so happy and satisfied and we ended our visit to La Côte with a wander around the lovely church and town.

I have one thought or suggestion for the museum. They really should produce a souvenir guide in several languages with photographs both of the house and some of the permanent collection. Wouldn’t that be a lovely reminder of what we have seen? I hope they will do this.

Now I just want to go back. After all I never did get to photograph that road sign!

Sue Vernon

April 2007

I first began listening to Berlioz’s music my freshman year of college. I was hooked the moment I heard the idée fixe theme, and wore out my stereo with the Fantastique. I listened further, to Faust, Troyens, Harold, the Requiem and Te Deum – everything I could get my hands on. Reading his Memoirs was a delightful experience and it remains one of my favourite books. (If anyone is interested, the book Berlioz Remembered, compiled of contemporary anecdotes about the composer, makes a nice companion read.)

During the revival year of 2003 I made a pilgrimage to New York, where I caught a performance of the Requiem, in Carnegie Hall. The tenor sang a singular “Sanctus” from one of the balconies; the “Dies Irae” was staggering.

A year later, I was fortunate enough to make a trip to Paris, where I was disappointed by Berlioz Square, a tiny park in an out-of-the-way neighbourhood that contains what I consider a rather poor sculpture of the composer. I proceeded on to London where, at one of the book sales along the Thames, I made a mistake that I regret to this day – I passed up a copy of David Cairn’s biography signed by Cairns himself! What was I thinking?! Sure it was expensive, the exchange rate had taken me for a sucker, and my bags were already stuffed, but I should have sprung for it. Oh well, I’ll always have Paris...

To me, Berlioz remains one of the most human of the great composers, a creator of beautiful music, a man who struggled his whole life because he simply knew that he must; I have often wished to be able to feel as he must have, to be as moved by music, to have such finely tuned sensitivity and such a passionate temperament.

David Friesen

As a natural culmination of more than two years’ immersion in the life and creations of Hector Berlioz, I paid a visit to the Berlioz family home in La Côte Saint-André in May 2006, in the company of fellow Berliozian Alan Merryweather. Although I have often wished that Berlioz had been given a museum in his adoptive city of Paris to provide greater access, having seen his family home in its natural setting, I now believe that his museum is appropriately located. The creator of Harold en Italie, the fantastique, Cellini, Béatrice et Bénédict, and Les Troyens belongs to this exquisite rural setting of sunlit farmlands and winding rivers within the frame of rock-faced hills and distant snow-capped Alps far more than to the teeming avenues and boulevards of Paris, although they have their legitimate claim on him as well.

Our first visit day, however, was far from the sunny ideal I could imagine. To begin with, I got us lost on some back roads after being confused by a sign to an alternate route. There were tense moments as we looked at our inadequately detailed map for guidance out of the maze. Eventually we wound our way back to the highway, almost back at the source of the original mistake. Too bad we were too anxious to enjoy the lovely scenery of woods and lake! Then, at long last arrived in La Côte, an unseasonably cold and wet wind assailed us at the feet of the Berlioz statue in Place Hector Berlioz, which now finds itself out of necessity converted into a city car park, not the most attractive setting for such a lover of beauty as Hector. Grey skies served as a backdrop for my photos of the master, reflecting as he leans against his podium. We were happy to find shelter through the open blue doors of the stately old Berlioz home just a couple of blocks up the hill. Oddly enough, its front with its iron grillwork and tall wooden shutters reminds me of homes I’ve seen in photos of New Orleans.

We were greeted by two gracious receptionists who issued us honorary tickets at no charge after inquiring the names of our home cities and countries. On a late Wednesday morning in early May, we had the house to ourselves. Such a privilege! We began with the very large displays on the ground floor which provided an overview of the high points in Berlioz’s life as they influenced his compositions. These displays were well illustrated with period prints and photos. I wished for English translations, but, after all, I was in the depths of la belle France! And, to be fair, I had passed up the opportunity to rent headphones with English commentary. I was rather surprised that the introductory displays were not arranged chronologically (or such was my impression).

The house is constructed as though it were two houses fused back-to-back on different levels, for one must climb a staircase to reach the rear of the house, with its garden. This was true of the transition from the front to the rear of the house on each level. The public rooms (what was perhaps the doctor’s surgery and above it several drawing rooms) and the master bedroom occupied the front of the house, along with some smaller rooms on the top floor above; the rear contained the kitchen, dining room, the doctor’s study, and the children’s bedrooms. There was also a spacious basement, now housing an intimate theatre/lecture room and modern washrooms. It was a touching experience to enter Hector’s childhood bedroom behind his father’s study on the middle floor, one of the most remote and hidden rooms in the house. I wonder whether he felt a captive there, with interior access only through his father’s study. (I do remember a second door from Hector’s room to an exterior balcony running the length of the garden side of the house.) The room was painted a sort of Wedgwood blue with (if memory serves me correctly) a scrollwork painted in deep rose along the top of the walls. These colours, discovered during restoration, were described as original to the room. Hector’s bedroom featured only one rather small window in its deep outer wall which did not supply much light and reinforced my impression of its dungeon-like quality. Overall, I was surprised at the size and grandeur of the house as well as its almost Italianate appearance from the garden side.

For someone who is fascinated with Berlioz, the museum is a treasure trove of delights. The originals of family portraits and photographs, autograph scores, original letters, presentation batons and silver wreaths, travel notebooks, a few musical instruments from the period, and proclamations from royalty honouring Berlioz – too much to absorb in a single day. We returned two days later (this time without losing our way) to revisit the letters and scores. I regretted not having enough time to read all the many letters stored in illuminated drawers on the top floor. Also on the top floor of the front of the house, we encountered a display which played selections from Berlioz’s works. (I personally would have enjoyed Berlioz’s music to be played softly throughout the house, but perhaps others would find it distracting.) His music was playing softly in the theatre in the basement. When we returned after our lunch break, the receptionists kindly played the television film Moi, Berlioz just for us in the theatre. Running nearly an hour, it is a dramatisation of key moments in the composer’s life, with wonderful clips from performances of his music. Would that the film were available on DVD for purchase! The receptionists assured us that it is rare and unavailable.

Of all that we saw and experienced in the museum during our two visits, nothing moved me more than the plaster head of Berlioz modelled from his death mask. I first saw it in a photograph in Barzun’s Berlioz and the Romantic Century, but seeing the original and knowing how it was made brought Berlioz the man closer to me than any of the other artefacts. How sad his sunken face looked, with its beak of a nose and its frame of wild hair, apparently scattered against his pillow! Beside the sculpture was a long lock of Berlioz’s coarse white and curly hair, also bringing the person alive for me.

What would I have had different in my experience of the Berlioz museum? Having the captions for the displays placed with the displays rather than, as often happened, at the nearest doorway or on a hard-to-read panel nearby, would have made viewing more convenient. I did appreciate the reproductions of the portrait or document found alongside the captions as a key.

Is it presumptuous of me to request English translations beneath the French? (An analysis of the home country data requested at the ticket counter would provide an answer regarding numbers of English-speaking visitors.)

I found the lighting throughout the house maddeningly inadequate. Many portraits and illustrations on the walls or in cabinets needed their own illumination. I also thought that captions were often in print too small for convenient reading by more than one person at a time, but better lighting would have helped.

I would have liked to see more furniture from the period throughout the house. However, I was so pleased and touched to see one tasselled armchair surviving from Berlioz’s Paris apartment in the master bedroom and the Erard piano which he bought for his nieces in the drawing room. I remember another period piano and a music stand similar to the one on the Berlioz statue. The kitchen was nicely re-fitted so that I could imagine the cook working and, indeed, living in there (for there was a bed in the alcove). I would have liked to have the same sort of impression about the rest of the house, but space probably would not allow for both exhibits and furniture.

Finally, I sincerely hope that the grand old Berlioz house soon receives a well-deserved fresh coat of paint, especially on its garden side!

In the ground floor reception area an interesting array of books and postcards of Berlioz was on sale. Since taking photographs is not permitted, I would have liked more than the one postcard of the house’s interior. I was surprised that the publications of the ANHB (Association Nationale Hector Berlioz), headquartered in the house, were not also on offer, but probably there is some regulation which makes this impossible.

It is my dearest hope that this account has inspired the reader to visit or re-visit the Berlioz house museum in La Côte St. André. Like the musical and literary masterpieces of Berlioz himself, it will yield its beauties to those who take the trouble to find it, to linger, and to reflect on what influences are at work in the development of genius.

Mary Weber

San Diego, California

May, 2006

I come from Slovakia and I am one of those devoted Berlioz-lovers one can find all over the world. My enthusiasm for Berlioz started – not surprisingly – with hearing the Fantastique, many years ago, when I was about 14-15 years old. Then it was Harold that made me love the viola tone, then I heard some excerpts from Roméo and my love affair with Berlioz and his music continued.

Thanks to the Institut français in Bratislava I had a chance to discover much of his music that I had not known before, including those legendary recordings by Sir Colin Davis. Some two years ago, I noticed a CD of the Messe solennelle conducted by J. E. Gardiner. A fantastic piece! Beauty combined with fierce temperament. And what a performance! An astonishing originality, richness of melodic invention and a masterful orchestration. Energy of a young man breaking conventions. He was 21 when he wrote it, and the themes of his later, more famous works can be heard here. This work is simply a must for every Berlioz-lover!

My great desire, since I’ve known the work, is to hear it performed live here in Bratislava, with Mr. Gardiner conducting. As far as I know, it has never been performed in Slovakia. Bratislava’s St. Martin’s Dome would be an ideal place for it. Handel’s Israel in Egypt, Bach’s Mass in B minor and Pärt’s works have been successfully played here, and I believe that Berlioz would receive an equally warm welcome especially from young listeners...

Robert Kolar

Bratislava, Slovakia

I would just like to add that what really attracted me to Berlioz’s music was that upon listening to his Requiem, it frightened the hell out of me! I listened to the “Dies Irae” of his Requiem, with the beatings of a dozen bass drums, and wow, what a sound effect! I had no idea such terrifying sounds were possible to be produced in the 1800s. But Berlioz totally managed to capture the hellish and horrific aspects of the human psyche with his music. In particular, the bells that ring in the Witches’ Sabbath movement of his Symphonie fantastique was a work of genius. You cannot help think about Death and the macabre when you hear that music.

Alessio Rastani

London, UK

I first want to thank Drs Tayeb and Austin for such an amazing site. It is unreal that such a comprehensive site with all this data can be found about my favorite, yet mysterious composer. I have been visiting this site since 1999, when the content, already impressive, was not nearly as broad as it is today. I can’t express my gratitude for the site enough.

I must start the story of my life with Berlioz from the beginning, for I am amazed myself how I was ushered into the complexly exquisite – and exquisitely complex – life as a Berliozian. Anybody who encounters me knows right away that I have an obsession with this "Frenchy" – and though it turns heads here in America, especially among my contemporaries, I am adamantly unapologetic for this infatuation.

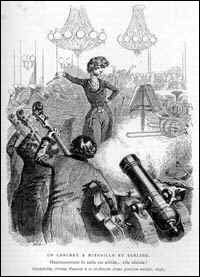

As I’m still a young impressionable man, I am susceptible to acquiring overblown passions for what might be very small subjects. So was the case in my eleventh year – with considerably more power – when I saw for the first time this famous caricature of Berlioz:

There is something that triggered within me a “love” for this man in the picture. I knew not his music, nor his story – or why indeed he was depicted in such a mocking fashion. But, as the old adage goes, “a picture says a thousand words”, I was overtaken by a sense that this man in the picture was larger than life in many ways – his music notwithstanding.

At the time, since I was just a kid and unfamiliar with this man, or even his name, I’d pronounce his surname “Berli-Oz” as in “The Wizard of Oz.”, I was always looking for some kind of reference about him, concerts featuring his music, recordings of his music – anything that would make me more familiar with this figure in the caricature.

Soon (I was about 14-15 years old) I came across a cheap recording of the Fantastique conducted by Alberto Lizzio on the Piltz label, in a discount store. I was infatuated! I’d certainly never been in love by then, but I was in love now! I listened to the recording at least three times a day, every day, until it was coming out of my ears. I could just not get enough of Berlioz. The Fantastique is all I had, however.

I devoured whatever information I could about Berlioz and I found some very interesting facts – which I found later to be incomplete or flawed, for the most part – and I was now impressed by the man as much as the composer. I could not imagine how a man, who wrote such outstanding music, did not play a single instrument! Of course it is not entirely true – we know he was quite good at playing the guitar, flute and timpani; but I found that fact very "cool" at the time. I was also intrigued by a weird instrument he wrote for – the viola. Again, I was a young kid with not much knowledge about music, despite my overpowering love for it.

I wanted to hear what the viola sounded like and how Berlioz of the Fantastique could pull off an impressive work for Paganini for this instrument. (I was always familiar with Paganini – long before even encountering Berlioz.)

Soon I took out a recording of Harold en Italie from the library with Toscanini and his principal violist Carlton Cooley – and I was smitten with love for this composer all over again!

At around the time I came across this site I was 17-18 years old, and I was desperately seeking to own some more music of this amazing composer. I was particularly looking for that second symphony – the viola symphony.

The summer I came across this site was fruitful musically in many ways. I, a New Yorker, was spending the season in Iowa (a place close to every Dvořák lover’s heart; in fact I was not far from Spillville, where he resided) and I had many opportunities to do “research” on the many musical topics I was curious about. I guess I started my musicological career that summer.

I came across the double CD of Bernstein/Previn on the EMI label of the first two symphonies and overtures on e-bay, and promptly bought it. I still don’t like the recordings of the symphonies to this day, but Previn’s overtures surely are pretty good.

Over the ensuing years my awareness, knowledge, appreciation and larger-than-life love for Berlioz just grew and grew.

I was very aware about the bicentennial that was approaching, and I had only one idea of how a Berliozian can spend it. I had to go to la Côte St-André. I put together the money, made my impulsive plans (that means no plans) and made my way to the airport for a Berliozian experience in France!

Thankfully, there was a large snow fall in New York on the day of the flight; the flights were running on time; I missed mine… I’m thankful, because if I’d gone I’d still be there, a fugitive of the law; I ran out of money before I even got to the airport. Of course, this ordeal would not be unlike similar experiences in Berlioz’ life; but this is the 21st century.

Dejected, I returned home, not knowing how I’d celebrate my ‘Musical Grandfather’s’ birthday. By chance I heard that Susan Graham was going to be joining some Berliozians in New York City at a pub known for its musical stage (Joe’s Pub) and sing/talk Berlioz on December 11th. I promptly made my way to NYC that evening. Tim Page, the renowned musicologist/journalist, of New York Times, Newsweek and Washington Post fame, was going to be there to address the gathering.

It was the most awesome experience I ever had. It is now 2006, and I still remember that night as vividly as if it were yesterday. Susan Graham ended the “concert” with the first two songs of Les Nuits d’été. It was so amazingly heartfelt; she and everybody else in the room wore their hearts on their sleeves, and I could really feel the impact of the words that made up the motto of the evening, “THEY ARE FINALLY GOING TO PLAY MY MUSIC”, Berlioz’s very last words…

I left the pub on a cloud. Later that winter I went to two Berlioz performances at Lincoln Center, conducted by the two greatest Berliozians alive today, Sir Colin Davis and Charles Dutoit. The violist of the Davis concert was Paul Silverthorn; he is an amazing violist and his reading of the symphony was uniquely exceptional, considering I had heard many readings by various violists.

Since that Year of Berlioz many things have occurred in my life, including my decision to go to college. As I am a composer, following Asger Hamerik’s example, I seek out the spiritual and practical side of Berlioz, in order to create my music in tribute to Berlioz and his unique insight.

I am a Young Turk at the age at which Berlioz was already working on his Messe Solennelle. I therefore have to take his example and work harder at maintaining his vision for the future.

I have clear plans to conduct in the near future and expose Berlioz to the world for what he truly was – the greatest Romantic composer in history… and that is not an understatement!

David Teitelbaum

This passion started fifteen years ago. As a teenager, I knew La Fantastique as anybody else but never thought of going farther in his music. But in 1990, I suddenly found myself alone and helpless so I remembered Berlioz. I therefore went to the record-dealer and enquired about the available selections for Berlioz. The clerk answered “You know he did not compose much and it is mostly vocal music”.

At the time I did not like vocal music and I told myself that Berlioz must lack inspiration. In spite of this I asked if he had composed another symphony, so I bought Harold en Italie. I liked it so much that I decided to take a risk and purchase a vocal piece called La Damnation de Faust which I simply adored! I have been wiped off my feet ever since!!! I read the Memoirs in which I liked so much his strength of character and sense of humour that I bought all his recordings as well as his writings including his correspondence.

I must say that he is as much a great writer as he is a great composer. I must pay tribute to Maestro Charles Dutoit who has done so much for Berlioz in Montréal. The moral of all this is that we should perhaps not discourage customers who wish to explore the works of composers. I end by stating that maybe we should stop denigrating him and take him as he is.

Thérèse Bédard

Montréal, Québec

Canada