![]()

|

|

|

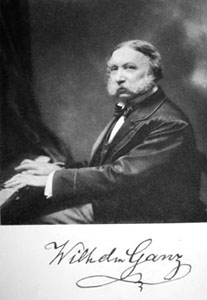

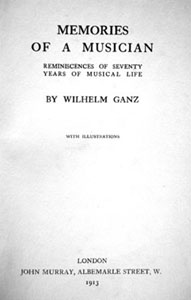

This page presents a transcription of extracts relating to Berlioz from Wilhelm Ganz, Memories of a Musician. Reminiscences of Seventy Years of Musical Life, London, 1913, a copy of which is in our collection. On the Ganz family of musicians and its relations with Berlioz over a period of 3 generations, see the page Berlioz in London: friends and acquaintances.

We have preserved the original syntax and spelling of the text, but corrected obvious type-setting mistakes. We have also clarified and/or pointed out in footnotes certain factual errors by Ganz, who for the most part wrote his reminiscences many years after the events described in the book.

![]()

I was a boy of fourteen when I came to London with my father in 1848, having been born on November 6th, 1833. My father, Adolph Ganz, had been for more than twenty-five years Kapellmeister at the Opera at Mainz, on the Rhine, and the Grand-duke of Hesse-Darmstadt bestowed on him the title of Grossherzoglicher Hofkapellmeister – Grand Ducal Court Conductor. He brought the opera there to a high pitch of perfection. It was his forte that he could conduct most of the classical operas from memory – I mean, without having the score before him – and could also write out each orchestral part from memory. Furthermore, although self-taught, he could play every instrument in the orchestra.

![]()

When my father and I came to England in 1848, I find I made the following entry in my diary:

“Friday, Feb. 18th. – Left Mainz…. We arrived in London on Sunday night, 10.30, and drove to Brydges Street.

“Monday. – Went to see Balfe, who received us in a very friendly way; then went for a walk. I cannot describe the impression it made upon me; so many beautiful shops, and so many carriages that one could not walk on the road, but had to keep to the pavement.

“In the evening went across to Drury Lane Theatre and saw the opera. Berlioz was conducting Figaro.”

The late Michael William Balfe, composer of the ever-popular Bohemian Girl and many other operas, was the conductor at Her Majesty’s Theatre, and Mr. Benjamin Lumley was the director. Balfe had known my father before, and had suggested his coming and settling here.

![]()

In 1855 came the first performance of Il Trovatore. I was asked to teach Madame Ney-Bürde, a prima donna from Dresden, the part of Leonora, which I did. She had a magnificent and powerful soprano voice. Madame Viardot Garcia was superb as Azucena, Signor Tamberlik was the Trovatore, and Signor Graziani (the incomparable baritone) sang the part of the Conte di Luna. Tamberlik studied with me Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète, and also the title-rôle in Hector Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini. I was present at the first performance of the latter opera on June 25th, 1853. Berlioz conducted it himself, but it had no success, and was withdrawn after the second performance.(1)

My disappointment was great, as I had also coached Madame Nantier Didiée for the part of Ascanio. My diary says:

“May 22nd. – To Madame Didiée. M. Berlioz there: tried over Madame Didiée’s part for his opera Benvenuto Cellini, which is to be produced at Covent Garden under his direction. He beat time and I accompanied this difficult music prima vista.”

In order to give Tamberlik his lesson I had to be out at Haverstock Hill, where he lived, by seven o’clock in the morning. I had to walk all the way because at so early an hour I could not get a cab, nor could I have afforded to pay for one in those days. He used to practise with me for some time – although he was always hoarse in the morning – and afterwards he had a fencing-lesson and then his breakfast. He was a fine artist, and was splendid as Jean of Leyden in the Prophète, singing the aria “Re del Ciel,” with its famous high C (better known as the Ut de poitrine) from the chest, with great effect. Tamberlik had not such a beautiful voice as Mario, but he had more power in his high chest-notes, and was, perhaps, also more dramatic in his acting. He had a fine, commanding figure, and was what I should call a tenore robusto. He was a good musician too, and had no difficulty whatever in learning the difficult rôle of Benvenuto Cellini – though, after all, what is it compared with the tenor parts of Wagner’s Ring?

![]()

Monsieur Jullien was the director of the English Opera at Drury Lane when I arrived with my father in 1848, and my father took me often there. Hector Berlioz, the celebrated French composer, was the conductor.

I heard many operas there in English, including Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, the night after my arrival [see p. 4 above], in which Miss Charlotte Ann Birch was the Susanna. She had a very fine soprano voice. Miss Miran, who had a lovely mezzo-soprano voice, sang “Cherubino”; unhappily she died while still young. Sims Reeves and many other well-known artists also appeared.

Balfe specially composed an opera called The Maid of Honour for Monsieur Jullien, but the season did not last long; as a matter of fact, I think Jullien mismanaged it. I was, however, highly gratified at hearing these performances in the National Theatre, and seeing Berlioz conduct. The orchestra was splendid, among the players being an old friend of my father’s, Herr Goffrié, who was one of the first violins. In later years he started a series of chamber concerts on his own account, called Les Réunions des Arts in the old Beethoven Rooms in Harley Street.(2) He brought out many new foreign artists, and I remember my uncles being engaged to play at some of them. Herr Goffrié afterwards went to California, and settled at San Francisco. Alas! no soirées of that convivial and artistic sort have since been established in London. During the usual interval tea and coffee were served to the audience, and they had an opportunity of mixing with one another and making the acquaintance of the artists; so they enjoyed themselves thoroughly. The Réunions were always well arranged, and only the best music was performed. I used to be the accompanist at them.

I remember going with my father in March 1848 on Sunday evenings to the musical receptions of Madame Dulcken, pianist to Queen Victoria, in Harley Street. She was the sister of Ferdinand David, professor of the violin at the Leipzig Conservatoire – the intimate friend of Mendelssohn, who dedicated his Violin concerto to him. I find in my diary:

“Sunday, March 19th. – After tea went to Madame Dulcken, where I accompanied Steglich (the famous horn player) on the piano. Molique and Berlioz were there. She lives in a fine house; there is a good piano in every room.”

It was at Madame Dulcken’s house that all the most distinguished musicians assembled, especially those who left Paris owing to the French Revolution. There I first met and heard M. Kalkbrenner, a German pianist, who had settled in Paris, Mr. Charles Hallé, who, as everyone knows, became one of the most important musicians in England and settled here, and Mr. Wilhelm Kuhe, who died here in October 1912, after residing in this country for more than sixty years, and celebrating his eighty-eighth birthday the previous December. He became, unfortunately, totally blind, and used to play the piano by touch only, but would play every day – of course, without music – for several hours.

Hector Berlioz used often to go there, and also his wife, an Irish lady who was a great Shakespearean actress, and before her marriage was Henrietta Smithson.(3) Berlioz had a fine, big head and a Roman nose, huge forehead, and piercing eyes.

Some of these pianists played during the evening receptions. Madame Dulcken often played Mendelssohn’s Concerto in G minor with Quintette accompaniment, played by my father, Herr Goffrié, myself, and two other instrumentalists, whose names I have forgotten; in fact, she was almost the first to make this lovely concerto known and popular – it was really her cheval de bataille. She was a very brilliant player, and a charming woman as well.

![]()

A memorable event in the spring of 1852 was the first series of orchestral concerts given by the New Philharmonic Society, which was formed by Dr. Henry Wylde with the special object of producing novelties and giving concerts of the best kind. Great éclat attended these concerts, as Hector Berlioz, after his triumphant tours throughout Europe, was specially engaged to conduct. The orchestra consisted of 110 performers, the leaders being all well-known soloists, such as Sivori, Jansa (violinists), Goffrié (viola), the great ’cellist Piatti, Bottesini, the famous contrabassist, Rémusat the flautist, Barret the oboist, and Lazarus the clarinettist. I was fortunate in being engaged as one of the second violins, and was much gratified when, during the first rehearsal, Berlioz said, “Ganz, I want you to play the small cymbals with Silas in the scherzo.” We were rehearsing his Romeo and Juliet symphony, which has a wonderfully light and fairy-like scherzo to represent “Queen Mab,” and he had two pairs of small antique cymbals made to give a particular effect in it. There were several orchestra rehearsals, which for England at that time was a really great innovation. Every one was intensely enthusiastic, and anxious to please Berlioz, who was a wonderful conductor. His beat was clear and precise, and he took endless trouble to get everything right. I remember him asking Silas and me to come and see him in King Street, St. James’s, just to try over the passage for the little cymbals. I mention this to show the care he took over every detail.

As a result, the first concert proved a veritable triumph for him, and it was generally admitted that no such orchestral performance had ever before been heard in England. The hall was crammed, and the audience was absolutely carried away and cheered him to the echo. There were similar scenes at all the following concerts. Perhaps the finest was the fourth concert, when the hall was packed to overflowing for Beethoven’s Choral Symphony. Up to then the work had never been properly given in England, as the old Philharmonic Society, although it owned the mighty score, would never give it more than their customary one rehearsal. In consequence it was still regarded as an unintelligible work. We had five rehearsals, at which Berlioz was indefatigable.(4)

The performance at the concert was masterly, completely realising all the grandeur and beauty of the immortal work, and the effect on the audience was electrical, Berlioz being called out again and again amidst perfect storms of applause. The singers in the symphony were Clara Novello, Sims Reeves, and Staudigl.(5) It was at this concert that I first heard the beautiful and poetical playing of Mlle Wilhelmine Clauss, in Mendelssohn’s concerto, an artist of great charm, who, unfortunately, only paid rare visits to this country. Berlioz gave selections from his Faust at a later concert (6), which again roused immense interest and enthusiasm. I was also in the orchestra in 1855, when he came again and conducted his Harold in Italy.

The concerts were most interesting and instructive to me, not only on account of the great privilege I had of playing under Berlioz’s baton, but also because in later years I was enabled, when I took over the New Philharmonic Concerts, to bring his great works once more before the English public. [see p. 137-9, 144-8 below]

![]()

In 1879, as Dr. Henry Wylde wished to retire from the enterprise [the New Philharmonic Society], I decided to continue by myself. I now became sole director and conductor, and I made various alterations in the orchestra, increasing it to eighty-one performers, and I engaged a number of distinguished first violins, some of whom were soloists. Mr. Politzer had been the leader for many years and I retained him in the same position. He was a first-rate leader in every way. I was determined to carry on the concerts with as much energy and perseverance as my health would allow. It was a hard task, as they were hardly a financial success either in Dr. Wylde’s time or from the time when I became associated with them.

As Berlioz’s music had been neglected for many years inconcert programmes, I wished to revive the interest in the works of this wonderful composer, and I performed his symphony Harold in Italy at the first concert on May 26th; it made a great sensation, and the Press spoke most favourably of the work and praised the performance. I first heard it under the direction of the composer at these concerts in 1855 at Exeter Hall, when I was playing the violin in the orchestra, and it then made a deep impression on me. I remember seeing Meyerbeer sitting in the audience at this concert. He was a small, slight man, with a very interesting face, and attracted a good deal of attention.

At my concert in 1879 Herr Joseph Strauss played the viola obbligato part which had been played by Ernst in 1855. The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh honoured the concert with their presence; the Duke had previously told me that he would go anywhere to hear Beethoven’s Overture to Egmont, with which I opened it. Another attraction at this concert was Beethoven’s Pianoforte Concerto in E flat, the “Emperor,” which was magnificently played by Charles Hallé. When I escorted the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh to their carriage at the end they spoke to me in German in most complimentary terms. I had beforehand given the Duke a pianoforte score of the Symphony to enable him to follow it with greater interest.

![]()

This concert [30 April 1881] was also noteworthy for the first performance in England of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, Episode de la Vie d’un Artiste, Op. 4. Single movements had been previously performed here, but the Symphonie had not been played in its entirety except by me. The work created a veritable sensation. It required an augmented orchestra and the following extra instruments: one flute, two bassoons, one contra-fagotto (7), two cornets, one ophicleide, one tympani, two large bells (which I had specially cast), and four harps (in my opinion the proper effect cannot be obtained with a lesser number), making a grand total of ninety-two orchestral performers. The second movement, a scène du bal, a charming waltz movement for which I engaged four harpists who came in with brilliant effect, was enthusiastically encored.

It is not for me to attempt a description of this, perhapsthe most characteristic work of Berlioz, and I can only hope that all my readershave heard it since then. To show the general interest the performance aroused Iappend an extract from Punch at the time.

AT MR. GANZ’S CONCERT

He. We are very late, but we are in time for the Fourth Part of this marvellous Symphonie Fantastique. A wonderful man is BERLIOZ.

She. Oh, charming! So original! I hope he’ll write many more Symphonies.

He (with a vague idea that BERLIOZ is no more). Yes, yes! He was a Russian, wasn’t he, by the by?

She (equally fogged). It is a very Russian name.

He (looking at programme). Now for it! Ah! – (pretending he knows it by heart) – this movement illustrates a deep sleep accompanied by the most horrible visions. How admirably those loud sounds of the violoncello express one’s idea of a deep sleep!

She (not to be outdone at this game of “Brag”). Yes, yes! Listen! Now he thinks he is being led to the scaffold to the strains of a solemn march. How gloomy, how awe-inspiring are those pizzicato touches on the violins!

He (having got another bit by heart). Grand! Grand! Just hearken to the muffled sounds of heavy footsteps! It is finished! Oh, massive! Oh, grand! Live a reverie in some old cathedral!

She. It almost moved me to tears. Nothing more exquisitely doleful have I ever heard!

Third Party (leaning over). How do you do? How are you? I saw you come in. How late you were! But you were in time for that third lovely movement.

He and She. Oh, grand! Magnificent! Superb! Solemn!

Third Party. The light rustling of the trees moved by the wind was so wonderfully expressed!

He (amazed). Eh?

Third Party. Yes, you noticed it, of course. Did it not conduce to bring to your heart an unaccustomed placidity, and to give to your ideas a more radiant hue?

She (confounded). What?

Third Party. Why, the Third Part.

He and She. Oh, the Third Part!

Third Party. Yes; and now you’ll hear the Fourth Part. Now you will hear a deep sleep accompanied by the most horrible visions. Ta! ta! [Exit, and their enjoyment is gone for the Concert].

Although some critics gave the work a favourable notice, several papers, and one in particular, cut the Symphony to pieces. This, however, did not affect me, and I repeated it at the next concert.

Berlioz had a hard fight in Paris to get his works performed, and it was only after his death that he was fully appreciated by his compatriots. Without being egotistical, I must confess to feeling proud of having brought his Symphonie Fantastique before the English public.

On May 28th I performed another of Berlioz’s great symphonies, his Romeo and Juliet, which had not been given here for some time – so I revived it. I took great pains to give it adequately, as it requires two singers (8) and a chorus, which I had to provide. One of the movements, a scherzo, is called Queen Mab, in which two cymbales antiques (little antique cymbals) are used. This reminded me of the time [see p. 60-63 above] when the work was performed for the first time in England under the direction of the composer at one of the New Philharmonic Concerts in 1852, then started by Dr. Wylde, when Berlioz asked me to play one of these little instruments in conjunction with Edouard Silas.

Well, this symphony, under my direction, was well received – it is a fine work and most poetical. The Queen Mab scherzo is very difficult to play, as the composer has indicated the tempo prestissimo, but it went well. Miss Ellen Amelia Orridge and Mr. Faulkner Leigh were the singers who took part in it – poor Miss Orridge, who had a fine contralto voice, unfortunately died soon after, in the height of her career.

![]()

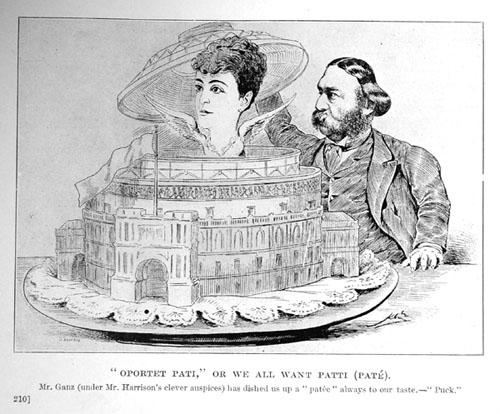

Shortly after one of [Adelina] Patti’s concerts, at which I conducted the orchestra, Puck had an excellent cartoon with the following verses :

“OPORTET PATI” “WE ALL WANT PATTI !” ’Tis said that Hector Berlioz once wrought (9) “Oportet pati” was the monkish text Next came a cheerfuller interpretation The rendering by Berlioz devised Our version of the Latin saw shall be See ! PUCK has drawn her nestling in a pie— She leaves her island home and friends to reap |

|

![]()

Notes:

1. Berlioz withdrew Cellini after the first and only performance given on 25 June 1853.![]()

2. The Beethoven Rooms were in Queen Anne Street.![]()

3. Ganz is confusing Marie Recio with Harriet Smithson. It was Marie Recio who accompanied Berlioz during his visits to London.![]()

4. According to Berlioz there were seven rehearsals for this concert (CG no. 3287).![]()

5. The fourth soloist was a Miss Williams (A Ganz, p. 142).![]()

6. This was the sixth and last concert, held on 9 June 1852.![]()

7. There is no contra-fagotto (double-bassoon) in the score.![]()

8. Romeo and Juliet requires three soloists, two in the First Part, and a third (Friar Lawrence) in the Finale. Only two singers are mentioned, Miss Ellen Orridge and Mr. Faulkner Leigh. Was the Finale omitted? Ganz does not say he performed the work complete, unlike his claim for the Fantastique.![]()

9. There are at least two sources for this.

9a. In Adelina Patti’s album Berlioz wrote: “ Oportet pati ”. Les latinistes traduisent cet adage par “ Il faut souffrir ”, les moines par “ Apportez le pâté ” et les amis de la musique par “ Il nous faut Patti ” (CG, vol. VIII, p. 613, n. 1).

“Oportet pati”. Latinists translate this saying as meaning “We must suffer”, monks as “Bring on the pâté” and music-lovers as “We must have Patti”.

9b. In the Journal des Débats of 13 January 1863 (p. 2) Berlioz makes the same joke:

Seul M. Calzado … se moque des beaux orchestres, des chœurs nombreux, des costumes, des décors, de la mise en scène, mettant toute sa foi dans le vieil adage latin : Oportet pati, que les savants de l’Académie des Inscriptions traduisent par : Il faut souffrir ; les moines par : Apportez le pâté, et les abonnés du Théâtre-Italien par : Il nous faut Patti.

M. Calzado … has no time for good orchestras, large choruses, costumes, stage-sets and staging, and puts all his trust in the old Latin saying: Oportet pati, which is translated by the scholars at the Académie des Inscriptions as: We must suffer, by monks as: Bring on the pâté, and by season-ticket holders at the Théâtre-Italien as: We must have Patti.

![]()

See also on this site:

Berlioz in London

Berlioz in London: friends and acquaintances (Wilhelm Ganz)

Charles Hallé on Berlioz

![]()

The Hector Berlioz website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 1 March 2009.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the information on this page. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil

![]() Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains

Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains