![]()

This page is also available in French

![]()

The thought of being a doctor, of studying anatomy, of dissecting bodies, of witnessing horrific operations, instead of surrendering body and soul to music, the sublime art whose grandeur I could already imagine! [...] No! This seemed to me to turn the natural order of my life upside down. [...]

Thus Berlioz in chapter 4 of his Mémoires in which, after relating his discovery of music while still a young man at La Côte-Saint-André, he recalls how he was confronted with the necessity imposed on him by his father to follow in his footsteps and study to become a doctor. The following chapter (chapter 5) relates the sequel when he arrived in Paris in the autumn of 1821: despite his aversion for medecine and growing passion for music, he persevered loyally for a while in studying the subject. The early autobiographical sketch which Berlioz wrote late in 1832, which is reproduced on this site in the original French, is specific on the timescale involved:

Shortly after [his early years at La Côte-Saint-André] Berlioz came to Paris in order to complete at the Faculty of Medicine a course of studies for which he was so ill-suited. He saw the dissection amphitheatre as well as the Opéra. Placed thus between death and pleasure, between hideous corpses and ravishing dancers, between the music of Gluck and Bichat’s prose, he nevertheless kept for a whole year the promise he had made to his father to follow assiduously his course of study.

The records of the Faculty of Medicine bear this out: from his arrival in Paris in November 1821 till November of the following year he signed on regularly for attendance at classes, but then ceased after this date. Very few letters of Berlioz have survived for the early period of his student life in Paris, but one letter to his sister Nancy, dated 13 December 1821, gives a hint of his inner struggles (CG no. 10):

You ask what are my pleasures and my sorrows. For the latter I will reply with La Fontaine: « Absence is the greatest of evils » ; but there are others, caused at times by a disgusting course of studies, and at times by the discouragement I often experience, when after working obstinately, I reflect that I know nothing, that father will perhaps not be pleased with me, that perhaps… I know not what. I would not end if I wanted to describe to you all the sad thoughts which assail me.

The sequel of the letter goes on to relate the compensating delights of life in Paris: the history lectures of Lacretelle, and above all the visits to the Opéra, where on 26 November he heard Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride. The Mémoires (chapter 5) relate his very first visit to the Opéra shortly before this, when on 14 November he heard Salieri’s Les Danaïdes, then on 18 November Méhul’s Stratonice (as the letter to his sister shows, he did not have to wait as long as the Mémoires imply to see a production of Iphigénie en Tauride). These experiences at the Opéra, and his frequenting of the library of the Conservatoire which started a few months later, changed his life completely; he decided that come what may he would abandon medicine and become a composer.

All the same, Berlioz’s single year as a student of medicine left lasting traces in his subsequent life. His aversion for the subject did not translate into hostility towards his teacher, the great surgeon Amussat, who became a lifelong friend (Mémoires chapters 5 and 53; see the commentary on a letter of Anna Banderali). Berlioz admired Amussat greatly, whom he described as an ‘artist in anatomy’. One might suggest that the same could be applied to Berlioz in reverse, that he was an artist with an anatomical bent of mind. Part of Berlioz’s intellectual make-up was a capacity for detachment and analytical objectivity, which he could apply to himself and his own works, as well as to others. This characteristic he displayed from his very first contacts with anatomy, as he relates in the Mémoires: his initial reaction on entering the dissecting room for the first time was one of horror and revulsion, but the next day he was able to approach the same task with clinical coolness and even humour. A later example of this ability for clinical self-analysis is the description Berlioz gives of the physical effect that music had on him (see the opening chapter of À Travers chants). One may further point out that the word ‘anatomist’ had positive connations for Berlioz: he describes Alexander von Humboldt as ‘that great anatomist of the terrestrial globe’ (Mémoires, Travels to Germany I Letter 9), and the novelist Balzac as ‘that incomparable anatomist of the heart of contemporary French society’ (Mémoires, chapter 55).

Another trait of Berlioz which may have its origins in his contacts with anatomy is his fascination for the macabre; it was reinforced when he discovered Shakespeare through performances by an English company at the Odéon theatre in 1827 (the grave-diggers’ scene in Hamlet, for example, made a strong impression on him). Various instances spring to mind: apart from the role played by death in several of his compositions (the Symphonie fantastique, the Requiem, and other works), his writings provide further illustrations, such as the story of the funeral of a young woman in Florence during his trip to Italy (Mémoires chapter 43) or that of the reburial of Harriet Smithson in the larger Montmartre cemetery at the end of the Postface of the same Mémoires.

![]()

The photographs reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in 1999; the engraving is in our own collection. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

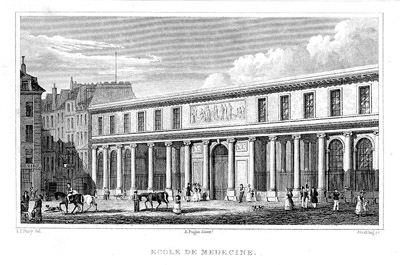

The main entrance of the Faculty, part of the Université René Descartes, is on the rue de l’École de Médecine, which links the present Boulevard Saint-Germain to Boulevard Saint-Michel, on the left bank of the Seine.

![]()

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page. Page revised and enlarged on 1st March 2017.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.