![]()

This page is also available in French

![]()

Berlioz’s marriage with Harriet, which had been in trouble by the early 1840s, ended in their separation in 1844. According to Berlioz himself, this was mainly because of Harriet’s unjustified jealousy, and her opposition to Berlioz’s travels abroad to give concerts (Memoirs chapter 51; cf. Correspondance Générale no. 1701 below [hereafter abbreviated CG]):

Under one pretext or another, my wife had always opposed my travel plans, and had I believed her I would to this day never have left Paris. Deep down the motive for her opposition was a mad jealousy for which I had long not provided any justification. To achieve my plan I therefore had to keep it secret, get my piles of music and a trunk adroitly out of the house, and depart abruptly leaving a letter to explain my disappearance. But I was not leaving on my own, as I had a travel companion who has followed me since in my various excursions. After being accused and tormented in a thousand ways, and always unjustly, and no longer finding any peace or rest at home, finally, with the help of chance, I assumed the benefits of a position of which I had been bearing only the burdens, and my life was completely changed.

To cut short the story of this part of my life and avoid dwelling on very sad details, I will only say that from this day on, and after many long and painful splits, my wife and I agreed to separate. I see her often, my affection for her has in no way been affected, and the poor state of her health only makes her dearer to me.

Berlioz moved in with Marie Recio (who later became his second wife) to her apartment at 41 rue de Provence, while Harriet on her side moved to 43 rue Blanche, and later to no. 65 on the same road. Some time in 1848, not later than July (cf. CG no. 1210), she moved to an apartment at no. 12 rue Saint Vincent in Montmartre, very close to the house where she and Berlioz had lived early in their married life. It is not known whether this was her own decision (Berlioz was in London at the time); at any rate the move brought her back to a place which had happy memories for her, and it was there that she was to spend the rest of her life. When in Paris Berlioz visited her frequently: rue Saint Vincent was within walking distance of Berlioz’s domiciles at the time (rue de la Rochefoucauld till 1849, then rue Boursault). She also received occasional visits from her son Louis, as well as from friends in Montmartre.

In October 1848 Harriet became gravely ill after a stroke which left her half-paralysed (CG no. 1236). The story over the next few years is known from Berlioz’s correspondence with his family, in particular his two sisters Nanci and Adèle, from which a few excerpts may be cited.

To Nanci (CG no. 1262, 5 May 1849):

[…] Harriet has been very well for a few days (relatively speaking), but she is becoming discouraged at not seeing movement return to her right side. She has to be misled all the time and given hope, and that is not easy. She has a garden which she finds very pleasant, particularly at this moment; she is carried there and seated among her lilac bushes, and the fine weather revives her a little. […]

To Adèle (CG no. 1335, 23 June 1850):

[…] Harriet has not been so well; she just about manages to make herself understood, but the slightest variation in temperature can cause new setbacks. Recently I caused her a painful experience when I sent her one of her portraits to place in Louis’ room; it was published twenty two years ago and shows her in the full bloom of her poetic beauty, none of which alas survives. She wept bitterly on seeing this all too faithful likeness of the past. And yet she thanked me effusively for the pain it caused her… Could there really be such sweetness in regrets and memories?… […]

To Adèle (CG no. 1437, 9 December 1851):

[…] Yes indeed the house of poor Harriet in Montmartre causes me grave problems, but in all honesty should this expense not take precedence over all others? What Louis wrote to you may make good sense from an economic point of view, but it was very wrong of him to speak to his mother about it without warning me, and I had the greatest difficulty in the world to erase from the ailing woman’s mind the impression made by these careless words. She might be reconciled to going to a nursing home, but the mere thought of leaving her own place, her garden, her flowers, her sun, her leafy lane, her view over the Saint-Denis plain, the open air, her two servants who I am sure are honest, distresses her deeply. She could not survive two months of imprisonment behind the cold walls of these dreary places known as nursing homes, and might almost die on arrival. I finally managed to persuade her that I had nothing to do with the proposition that Louis put to her on the subject. And this is the truth. I would put up with anything, living in a student’s room, eating stale bread, rather than inflicting on Harriet this mortal heart-break. […]

To Adèle (CG no. 1442, 16 January 1852):

[…] Harriet is still reasonably well. To answer your questions about the expenses for her house in Montmartre I will tell you that they amount to at least 3,500 francs a year when Louis is not there. The two servants economise as much as they can except for laundry, which is ruinous.

You see that my whole income is not enough for this expense and that I have to live on what I earn on top of my private means. […]

To Adèle (CG no. 1511, 17 August 1852):

[…] Harriet is still in the same condition, and is perhaps less unhappy than we think. During the summer season she is there at peace in front of her garden, with this fine view over Saint-Denis plain and the hills of Montmartre. She has two servants who are thoroughly attuned to her habits, lady friends who come to visit her from time to time and are not too intrusive, her newspaper which she reads two or three times in the morning, my visits and… hope… […]

During the next year Harriet’s health declined, as Berlioz wrote to Adèle (CG no. 1574, 5 March 1853):

[…] I said everything to his mother… she groans [a reference to Louis’ debts]. But she is herself so unwell that her mind is greatly impaired. She now needs a third woman to look after her, has to be carried out of bed and back again. Electric shock-treatment has not had any effect, and Alphonse Robert, whom I asked to have a word with her doctor, was of the opinion that this treatment should be avoided in future. […]

Harriet died on 3 March 1854. The story of her death and subsequent burial in Saint Vincent Cemetery is told in detail in a series of letters.

To Adèle on 6 March, in a letter written in Harriet’s own apartment (CG no. 1701):

Harriet died last Friday the 3rd of March [Berlioz writes ‘the 4th’ by mistake]. Louis had come to spend four days with us and had left for Calais the previous Wednesday. Fortunately she saw him again. I had just left her a few hours before her death, and came back ten minutes after she had breathed her last without pain or any movement.

The final ceremony took place yesterday.

I had to look after everything myself, the registry, the cemetery… Today I am very distressed.

She was in a dreadful condition; paralysis was complicated by erysipelas, and she had the greatest difficulty in breathing. She had turned into a shapeless mass of flesh… and next to her this radiant portrait which I gave her last year where she can be seen as she was with her great inspired eyes. Nothing remains.

My friends came to my assistance, and many men of letters and artists led by Baron Taylor took her to the cemetery in Montmartre which lies near the sad house.

And this dazzling sun, this panoramic view of Saint-Denis plain.

I was unable to follow the procession and stayed in the garden.

I had suffered too much the previous day when fetching pastor Hosemann who lives in Faubourg St-Germain. By one of these all too frequent cruel strokes of fate the carriage which was taking me had to pass before the Odéon theatre where I saw her for the first time 27 years ago, at a time when the élite of the Paris intelligentsia, that is of the world, lay at her feet… This Odéon where I suffered so much…

We could neither live together nor leave each other and we experienced this dreadful dilemma over the last ten years. We have suffered so much because of each other. I am just back from the cemetery, and am all on my own; she lies on the slope of the hill which looks towards the north, towards England where she never wanted to go back.

I wrote to poor Louis yesterday. I am going to write to him again.

What a dreadful thing life is!… Everything comes back at once, sweet and bitter memories! Her great qualities, her cruel demands, her acts of injustice, but her genius and her misfortunes… Horrible, dreadful! but I am unable to scream. She made me understand Shakespeare and great dramatic art, she endured misery with me, she never hesitated when we had to risk our basic necessities for a musical undertaking… then in contradiction of this courage she always opposed my wish to leave Paris and would not allow me to travel. Had I not resorted to extreme methods I would today be almost unknown in Europe… And her jealousy without reason, which in the end was the cause of everything which changed my life. […] I have kept her hair. I am there alone in the large sitting-room next to her empty room. Buds are beginning to sprout in the garden. Oh, to forget, to forget! who will take my memory away from me?… […]

And yet everyone tells me that we must be glad to have seen the end of her suffering; it was a terrible existence. I have had nothing but praise for the three women who looked after her. […]

To his son Louis, shortly after on the same day (CG no. 1702; this is the second letter mentioned by Berlioz in CG no. 1701; the first has not survived):

Poor dear Louis, you received my letter of yesterday; now you know everything. I am here all alone in the large sitting-room in Montmartre, next to her empty room. I am back again from the cemetery; I placed two wreaths on her tomb, one for you and one for me. I am not thinking straight; I don’t know why I came back here… The servants are still here for a few days. They are putting everything in order and I will try to make sure that what there is raises as much as possible for you. I have kept her hair; do not lose this little hairpin which I gave her. You will never know how much we both suffered because of each other, your mother and I, and it is those very sufferings which had made us so attached to each other. It was as impossible for me to live with her as to leave her. At least she saw you before dying. I had come the day before, a day after your departure and I returned ten minutes after she had breathed her last without commotion or pain. Now she is liberated. I love you, my dear son. […]

To Adèle (CG no. 1705, 11 March):

Oh yes you are quite right to tell me I must consider myself lucky to have been here; I cannot conceive the thought that she might have died alone… It would have been too terrible.

At least she saw her son who might not have come in my absence; she saw me a few hours before her death, she knew I was near her… Thank you for your letter and all the signs of affection that it contains. Instead of avoiding the place which has so many cruel memories for me I go there every day; every morning I go to the cemetery, and I suffer less than if I stayed away. It feels as though I am still going to visit her at home, only that she is more at peace… […]

I will be obliged to pay the rent for another year, if no one can be found to sublet.

I gave a few old clothes and two or three kitchen utensils to old Joséphine who had been in the house for at least ten years and who was recommended to me by Louis in his last letter. She will only be leaving in a month and I will give her a small gratuity.

I bought a plot for the tomb for 10 years, with the option of renewing the lease later if I am still in this world. […]

Finally to Louis (CG no. 1708, 23 March):

[…] I have just had a watch bracelet made for you with your poor mother’s hair, and I would like you to preserve it religiously. I have also had a bracelet made which I will give to my sister, and I am keeping myself the rest of the hair… […]

The remaining objects which I did not sell in Montmartre, your books, the portraits of your mother and of me, will stay in Paris in rue de Boursault, in a locked trunk which bears your address and a statement that it belongs to you. I gave two of my portraits to Joséphine and to Madeleine [the two servants], who asked for them. I also gave to Joséphine a few clothes which belonged to your mother. May God grant that my trip to Germany earns me some money! The apartment in Montmartre is not let and I may have to pay for it for another year. […]

In 1864 a part of the cemetery, where Harriet’s tomb was located, was planned to be demolished to make way for housing developments. Her remains were moved to Montmartre Cemetery, where Berlioz’s second wife Marie had just been reburied in a new tomb. Berlioz was forced to undergo the same painful experience. Harriet was reburied in the same tomb as Marie; Berlioz himself would join both of them in 1869. In his Memoirs (Postface) Berlioz ends the graphic description of the process by saying: ‘The two dead women now lie there in peace, waiting for me to bring my share of rot to this grave’.

![]()

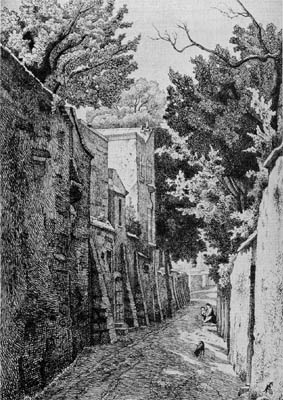

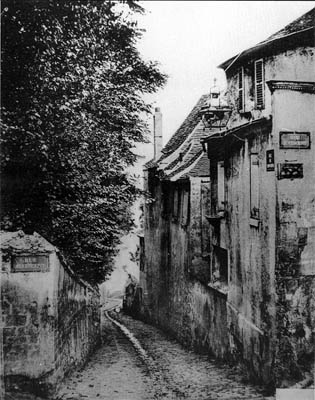

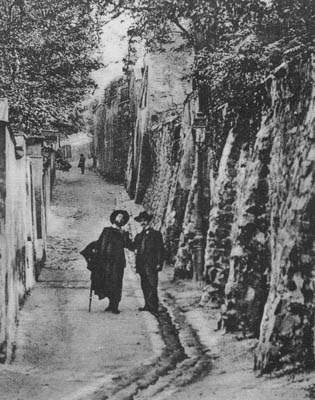

Unless otherwise stated, all the photographs on this page were taken by Michel Austin in June 2008. © Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved. The 1865 engraving of Rue Saint Vincent is courtesy of Jacques Hillairet, Dictionnaire Historique de Rues de Paris (Les Éditions de Minuit, 1997, 10th edition); the 1886 and early 20th century photos of Rue Saint Vincent are courtesy of Philippe Mellot, Paris disparu (Éditions Michèlle Trinckvel, 1996).

Rue Saint Vincent, on the north facing slope of Montmartre, runs straight down in an east-west direction for a length of about 400 m. The following photos give views of the road starting from near the top and progressing down in the direction of Saint Vincent cemetery at the bottom of the street.

Harriet’s apartment was at no. 12 rue Saint Vincent, as is known from the official inventory of her possessions drawn up after her death and dated 27 March 1854 (the full document is reproduced in Cahiers Berlioz no. 2, published by the Association nationale Hector Berlioz, 1995, pp. 23-7; cf. CG nos. 1702, 1705, 1708). The original house is no longer extant (see below for the present no. 12) and it is not clear where exactly it was located along this road, except that it was very near the house she had shared with her husband in 1834-6, and also had a garden with a view to the north over the plain of Saint-Denis (cf. above CG nos. 1262, 1437, 1511, 1701).

The building which replaced Berlioz’s home of the 1830s is the second on the left, at the point where rue Saint Vincent intersects rue Saint-Denis, which was renamed rue du Mont-Cenis in 1868.

Rue Saint Denis is on the right in this picture.

This is the first house on this side of the road, at the angle of rue Saint Vincent and the present rue du Mont-Cenis which intersects it in a south-north direction (in Berlioz’s time it was called the rue Saint-Denis). The present no. 12 lies at the junction of the two streets, diagonally opposite the modern block of flats which was built on the spot where Berlioz’s original home was located (see previous picture).

This is about half-way down rue Saint Vincent, looking up the street towards the east. On the right hand side is the fence of the old vineyard (next photo)

This is an old vineyard on the left hand side of the road, at the intersection of rue Saint Vincent and rue des Saules. This plot of land became the property of the City of Paris in 1933, with the object of preventing property development on this site of Montmartre hill and to preserve the memory of the vineyards planted on the hill (Hillairet, vol. 2 p. 489).

The wall on the right is that of Saint Vincent cemetery (immediately to the left is rue des Saules). Access to the cemetery used to be from rue Saint Vincent itself, but is now from rue Lucien-Gaulard lower down and on the other side.

The lower part of rue Saint Vincent, looking up to the east, with the wall of Saint Vincent cemetery on the left.

The above picture is courtesy of Philippe Mellot, Paris disparu (Photographies 1845-1930), Éditions Michèle Trinckvel, 1996, p. 278.

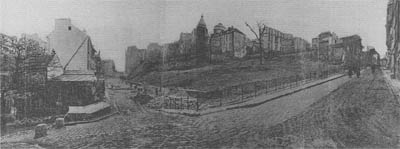

This shows the rue du Mont-Cenis running down from Montmartre

towards the north, at the intersection with rue Saint Vincent. The

present no. 12 rue Saint Vincent is to the left of this picture.

The above picture is courtesy of Philippe

Mellot, Paris disparu (Photographies 1845-1930), Éditions

Michèle Trinckvel, 1996, p. 277.

The above picture is courtesy of Philippe Mellot, Paris disparu (Photographies 1845-1930), Éditions Michèle Trinckvel, 1996, p. 275.

This shows the junction of rue des Saules (coming down from Montmartre hill on the right) and rue Saint-Vincent (around 1905?).

Saint Vincent Cemetery was opened on 5 January 1831.

This

alley within the cemetery leads to the present entrance of the cemetery

on rue Lucien-Gaulard, behind the car. From 1831 to 1905,

the entrance was in rue Saint Vincent where the present No. 40 is located (Hillairet,

vol. 2 p. 489).![]()

Rue Saint Vincent is behind the wall on the left (see also the next photo).

The above picture is taken from the opposite direction; here the wall which separates rue Saint Vincent from the cemetery is on the right.

Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955) painted many sites and buildings of Montmartre, a number of which had Berlioz’s home as their subject.

![]()

The Berlioz in Paris pages were created on 19 October 2000 (English version) and 20 October 2000 (French version). This page was created on 15 July 2009.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin for all the pictures and information on this page.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.