This page is also available in French

![]()

After years of waiting Les Troyens was finally performed at the Théâtre Lyrique and ran for a total of 22 performances from 4 November to 20 December 1863, the longest run of any work of Berlioz during his entire career (see in detail the page The Première of Les Troyens in 1863). But this came at a cost: for the purposes of this production Berlioz had to omit the first two Acts of the complete 5 Act Les Troyens and substitute a Prologue to provide the context for the last 3 Acts, which were now renamed Les Troyens à Carthage. This prologue comprised an introductory orchestral Lamento based on the theme of the duet of Cassandra and Coroebus in the original Act I, but now in a much slower tempo, which gave it the character of a funeral dirge over the fate of Troy and its people (see the page Les Troyens: orchestral excerpts). The Lamento was followed by a summary of the action of the first two acts spoken by a narrator dressed as an ancient rhapsode, who then introduced a compressed version of the Trojan March (for orchestra and chorus), based on the music of the finale of Act I. The statement of the Trojan March was musically necessary for the performances at the Théâtre Lyrique, since the march reappeared several times in Les Troyens à Carthage, but in a modified form; listeners therefore needed to be familiar with the original version of the march as it appeared at the end of Act I.

It may well be that the work in composing the new Prologue suggested to Berlioz that the Trojan March could well become a successful concert piece in its own right. The unsatisfactory compromise of the production at the Théâtre Lyrique thus had at least one positive outcome. Within a few weeks of the ending of the performances Berlioz was working on precisely such an arrangement, as emerges from a passage in a letter dated 19 January 1864 he sent to the publisher Antoine de Choudens, who had accepted to issue the scores of both Benvenuto Cellini and Les Troyens (CG no. 2827):

I have also started orchestrating and developing the Trojan March for concert performance; I believe it will make a splendid piece which could be played with great effect at the Conservatoire, at the Pasdeloup concerts, at those of Arban, everywhere. I am capable of giving a concert to have it performed, together with the Royal Hunt and Storm, played by an orchestra of the right calibre and conducted in my own way.

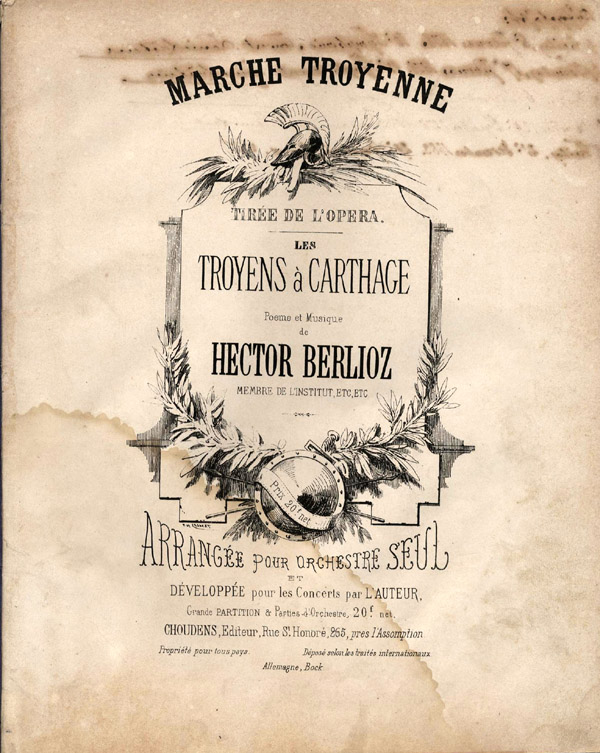

Over a year later, a sentence at the end of another letter of Berlioz to Choudens suggests that Choudens had accepted the proposal but was not keeping Berlioz informed of progress: ‘I have not heard anything more about either the orchestral parts or the full score of the Trojan March’, Berlioz wrote (CG no. 2991, 2 April 1865). In practice Choudens did publish the Trojan March with much greater alacrity than he did for the rest of Les Troyens: it appeared later in 1865 and was announced in a Paris journal in June of that year. We happen to possess a copy of this first edition of the March, the title page of which is reproduced below.

In practice the Trojan March was one of the very last works Berlioz composed, possibly even the last. According to Holoman’s Catalogue of the Works of Hector Berlioz (1987 - New Berlioz Edition, volume 25) there is no original music by Berlioz that can be securely dated to after this work. Berlioz felt that his career was now at an end, as he wrote to the Grand-Duke of Saxe-Weimar: ‘My task is now complete. […] I no longer write any prose, or verse, or music’ (CG no. 2857; 12 May 1864). This echoes Berlioz’s own statement in the Postface of his Memoirs.

Berlioz’s hopes that the Trojan March would prove a successful concert piece did not materialise in his lifetime, despite the fact that the piece was quickly published and thus made available. He himself never conducted the march in any concert in Paris, nor did he include it in any of his concerts in Russia in his last visit there in 1867-68. This was in spite of the keen interest of his Russian admirers for Les Troyens (they insisted on him sending a copy of the score to St Petersburg). Nor was the piece taken up by Pasdeloup in his own concerts, whether in Berlioz’s lifetime or after his death, though he did to some extent champion the music of Berlioz throughout his career as conductor. Among French conductors in the period after the death of Berlioz only Édouard Colonne included it in his repertoire. He performed it for the first time on 1st March 1874, which was probably the very first performance of the work since its publication (see the review of this performance by Ernest Reyer, a friend and admirer of Berlioz). Colonne performed the March several times subsequently. Among later conductors who championed the music of Berlioz it was a popular item; these included notably Felix Weingartner (who made a recording of it in 1939), Hamilton Harty and Thomas Beecham (who also recorded the piece, but in a cut version).

The main part of the march (bars 1-111) is adapted from the finale to Act I, though in a more condensed form and without the elaborate choral and orchestral forces used in the opera. Removed from its original dramatic context, where Cassandra’s prophetic warnings at the front of the stage play such a prominent part in the opera, the concert version of the march can therefore only give an incomplete idea of the impact of the music in the original version (this point was made by Ernest Reyer in his review of Colonne’s 1874 performance of the March). The end of the march (bars 112-167) is developed from music in Act V (nos. 43-44 in the full score, from the end of the first part of the Act, when Aeneas resolves to leave Carthage).

This page is reproduced from a copy of the first edition of the score in our collection.

![]()

Trojan March (duration 4'59")

— Score in large format

(file created on 12.04.2000; revised 10.07.2001)

— Score in pdf format

![]()

© Michel Austin for all scores and text on this page

This page revised and enlarged on 1st May 2022.