![]()

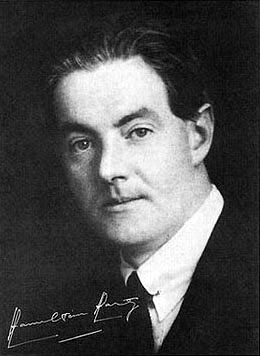

Conductors: Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941)

|

Conductors: Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) |

|

Introduction

Harty’s musical career

Harty and Berlioz

Chronology

Table of performances of music by Berlioz

Hamilton Harty on himself (1920)

Illustrations

This page is also available in French

See also: Hamilton Harty on Berlioz (1928)

Dibble = Jeremy Dibble, Hamilton Harty. Musical Polymath (London, 2013)

Plummer = Declan Plummer,

‘Music Based on Worth’: The Conducting Career of Sir Hamilton Harty, PhD thesis, Belfast 2011 (the full text is available online)

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.

![]()

Among conductors of the early 20th century, Hamilton Harty deserves special mention as probably the first British conductor to have actively championed the music of Berlioz in Britain, ahead, it seems, of his exact contemporary Thomas Beecham (1879-1961), who shared otherwise a similar enthusiasm for the composer. Up to the time of Harty and Beecham, music-making in Britain had been dominated by German musicians, and it was one of them, Charles Hallé, a friend of Berlioz, who pioneered the performance of his music in the country, in Manchester and London, from 1879 onwards. Many years later, in the 1920s, Hamilton Harty contributed by his conducting of Berlioz to spreading a new interest in the composer, which in time was to bear fruit in the country, as evidenced notably by the writings of W. J. Turner (Berlioz, The Man and his Work, 1934) and Tom S. Wotton (Hector Berlioz, 1935; reproduced in full on this site), though Wotton curiously failed to acknowledge what Harty had achieved for Berlioz).

Harty may not enjoy as high a reputation as other conductors of his time, such as Thomas Beecham, Felix Weingartner (1863-1942), Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886-1954), or Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957). His career was cut short by illness; he died relatively early in 1941 at a younger age than they did, and was not able to fulfil his potential completely. As a person Harty was a quiet and private man who did not seek publicity; he was outspoken in his often very personal views on music and musicians, but said little about himself. Unlike for example Beecham, Weingartner, or indeed Berlioz himself, it was only near the end of his life, in 1940, that he started to write his autobiography; but he did not live to complete more than a short sketch, which only covered his early years in his native Ireland down to his move to London in 1901. Furthermore, the largest part of his career thereafter was spent on the mainland of Britain. Unlike (again) Beecham or Weingartner, he only started conducting tours abroad at a relatively late stage in his career, in 1931, and most of his tours abroad were to the United States (between 1931 and 1936), with a single visit to Australia in 1934. Apart from single concert visits to Spain and Belgium (in April and November 1932), he never made any extended tours of the mainland of Europe (though he travelled there as a private individual, and had taught himself French, German and Italian). Frequent references in the Paris musical weekly Le Ménestrel, reproduced in the original on the French version of this page, show that Harty did enjoy a considerable reputation in France in the 1920s and 1930s, and in 1926 the journal mentions the plan for a possible visit by him to Paris to conduct Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, though this never materialised (Ménestrel 26/2/1926).

Harty’s achievement was nevertheless considerable, considering the disadvantages he faced at the outset. His formative years took place in his native Ireland, a country which on his own admission possessed at the time only limited musical resources — it did not have a proper symphony orchestra — and thus offered insufficient scope for his musical talents. He was largely self-taught, and did not have the benefit of the training and qualifications acquired at a musical or academic institution. His hopes for a career as a concert pianist were thwarted by his physique: his thumbs were judged to be too short. He came from a relatively modest background and lacked initially influential connections in the musical world of mainland Britain. Yet in spite of all these limitations, and through hard work and his own exceptional musical talents, he achieved in Britain and in the wider world a position of recognised eminence. He was an all-round musician proficient in several different fields: first as an accompanist who raised the art to a new and unsuspected level, then as a composer whose best works achieved recognition and popularity, at least in his lifetime, and finally as one of the finest conductors of his time, with a wide repertoire ranging from the classics to contemporary music, and famous notably as a dedicated champion of the music of Berlioz.

There is no need to give in this page more than a general outline of his career to put his championship of Berlioz in a wider context (a summary of the main dates in his life is provided in the Chronology below). The life and musical career of Harty have received detailed treatment elsewhere, notably in the 2011 Belfast PhD thesis of Declan Plummer, ‘Music Based on Worth’: The Conducting Career of Sir Hamilton Harty, and the 2013 book by Jeremy Dibble, Hamilton Harty. Musical Polymath, both of which have been of great assistance in the writing of this page; see further on this the table of performances below. (Incidentally, Dibble does not mention Plummer’s thesis in his bibliography or anywhere else, though both works cover some of the same ground.) The two works are referred to hereafter simply by the name of their author (Plummer’s thesis is unpublished, but the author has generously made the full text available online).

In an interview published in The Musical Times of 1 April 1920 Harty gave a brief and characteristically understated outline of his life and career up to his appointment in 1920 as permanent conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester. Substantial excerpts from this interview are reproduced below, and call for further comment and elaboration.

The fourth of no less than ten children, Hamilton Herbert Harty was born at Hillsborough in Co. Down in Ireland on 4 December 1879. He was born into a family of musicians, and from the start lived in an environment in which he was immersed in music. His mother played the violin and led the family quartet, one of his sisters played second violin, the viola was played by himself, and the cello by his father. His father was a professional organist and choirmaster at the Episcopal Church of Hillsborough; he had moved there with his family from Dublin the year before Hamilton was born. He was an all-round musician who possessed a large collection of books and musical scores; self-taught and distrustful of academic teaching, he was the greatest single influence on his son. Hamilton Harty was himself largely self-taught, an independent mind with a keen sense of his own worth, and self-reliant at times to the point of obstinacy.

Harty was born at a time when his country was undivided and part of Great Britain through the Act of Union of 1801. Harty was very reticent about any political views he may have held; in practice he accepted the Union, and in his 1920 interview was studiously silent about the contemporary troubles in Ireland which led to the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. On the subject of music in Ireland, he was critical of the limited resources available in the country, and of the lack of effort and ambition of young Irish musical students. But he remained deeply attached to his country and his Irish roots. This meant partly Ulster where he had spent his early years, and partly Dublin, where he went to settle in 1896 and met the Italian Michele Esposito (1855-1929), professor of piano at the Royal Irish Academy of Music; Esposito became a lifelong friend and mentor (he dedicated several compositions to him), and the second major musical influence on his life. Subsequently Harty made frequent return visits to Ireland, both Dublin and Ulster, and his own music is full of Irish associations, as manifested by the titles of several of his works (for example the Irish Symphony of 1904, the tone poem With the Wild Geese of 1910, or the tone poem The Children of Lir of 1939), but also by many of his other untitled works (a full list of his compositions is provided by Dibble, Appendix I, pp. 299-307, who discusses many of his works in detail). Reportedly it had been Harty’s ambition to end his career in Ireland and help to develop music in his native country. (An incidental footnote: Le Ménestrel refers to Harty twice [17/7/1931; 14/8/1931] incorrectly as ‘the English conductor’ — le chef d’orchestre anglais — an example of the frequent assimilation of all the peoples of the British isles to the English; music critics in the United States did not make this mistake, and regularly describe Harty as Irish.)

During the nineteenth century other Irish-born musicians had moved to the mainland of Britain in search of the opportunities they could not find at home: among them Michael Balfe (1808-1870) and Vincent Wallace (1814-1865), both of them acquaintances of Berlioz in London, later Charles Stanford (1852-1924), who for many years held a chair in composition at the Royal College of Music in London. Early in 1901 Harty followed their example and moved to London. He quickly established himself as an accompanist of exceptional ability, and was soon in demand everywhere on the part of the best singers and instrumentalists of the time. They were unanimous in their praise for his musicianship, sensitive playing and rare talents: these included the ability to sight-read any music and to transpose at sight, an exceptional memory, and an uncanny talent for anticipating the intentions of singers and players. He was, as the critic of The Musical Times wrote in 1920, ‘the prince of accompanists’, one who had raised the art to new heights: he was indeed more of a collaborator in a musical partnership of equals than just a subordinate accompanist. His success in this field enriched his general musical experience, and provided an essential preparation for his future career as conductor. It also brought him into contact with numerous singers and instrumentalists, among them the distinguished soprano Agnes Nicholls (1877-1959), whom he married in 1904. They performed frequently together for many years, and he wrote many songs for her. But in the long run the marriage was not happy; they did not have any children, and they eventually lived separate lives, though they never divorced.

While pursuing a career as accompanist Harty continued composing, and with some success. Composing orchestral works had the further advantage of giving him opportunities to conduct himself his own music. Conducting had indeed been Harty’s ultimate ambition from the time he arrived in London, if not earlier. He submitted his Irish Symphony to the Feis Ceoil in Dublin in 1904 and won the prize; it was his first experience of conducting (he conducted the work again in Dublin the following year). He similarly conducted the first performances of his Ode to a Nightingale at the Cardiff festival of 1907 (with Agnes Nicholls singing the vocal part) and of his tone poem With the Wild Geese at the same festival in 1910. In the meantime he had given in 1906 his first complete concert, conducting the British Symphony Orchestra at Queen’s Hall in London. His marriage with Agnes Nicholls also opened up important connections, among them an introduction to the veteran German musician Hans Richter (1843-1916), conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester from 1899 to 1911 and of the newly-founded London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) from 1904 to 1911. Harty first conducted the Hallé in 1913 and the LSO in 1911, orchestras with whom he was to develop a close association in subsequent years. By the eve of the first world war Harty had developed a substantial reputation as a conductor in his own right.

The outbreak of war indirectly assisted Harty’s conducting career. Despite the pressures of war, musical life in Britain continued without major interruption; but whereas prior to the war German musicians such as Hans Richter had played a major part in the musical life of the country, Britain was now forced to rely much more on its own home-grown musicians, and Germans were for the time being no longer welcome. Harty was one of those British conductors whose services were repeatedly called upon, and it was during the war years and immediately after that he developed a closer rapport with, in particular, the Hallé and the LSO. His great opportunity came early in 1920. During the war years the Hallé had lived from hand to mouth with a succession of temporary conductors, Harty one of them. It was now felt that it needed the stability of a permanent conductor, and on the recommendation of Thomas Beecham, who had himself done much to sustain the Hallé during the war, and evidently appreciated Harty’s talents, Harty was offered the post of permanent conductor of the orchestra, starting with the 1920-1921 season.

Harty accepted the post, and went on to hold it continuously for over a decade from October 1920 to April 1933. His appointment marked a turning point both in his career and in the fortunes of the Hallé orchestra. Previously the permanent conductors of the Hallé had all been German: Charles Hallé its founder (1857-1895), then Hans Richter (1899-1911), who was succeeded by Michael Balling (1911-1914). Under Harty’s direction it very quickly rose to become once more what it had been under Charles Hallé, the finest orchestra in the country, which set a standard that the London orchestras could not emulate. Though it did not undertake any tours outside the British isles (but Harty took it on occasion to Ireland), its reputation spread abroad, as attested for example by frequent references in the Paris musical weekly Le Ménestrel throughout the 1920s (see notably Ménestrel 3/11/1922, 17/8/1923, 23/11/1928, 29/11 and 27/12/1929). After years of financial stress it was able to become financially profitable (Ménestrel 12/9/1924). As well as giving regular concerts in Manchester and neighbouring cities, the Hallé was also a frequent visitor to London (cf. Ménestrel 12/9 and 14/11/1924, 23/11/1928, 10/1 and 28/11/1930). With the foundation of the British Broadcasting Company in 1922, nationalised in 1927 as the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), a number of the Hallé concerts started to be broadcast from 1923 onwards. From the beginning of Harty’s tenure the orchestra also started to make commercial recordings, using initially the more restrictive acoustic method, then from 1925 the more developed electrical technology which permitted the use of microphones and full orchestral forces (a full list of Harty’s recordings is provided by Dibble, Appendix 2, pp. 308-29; for his Berlioz recordings see below). After Harty’s eventual departure, his period as conductor lived on in the memory of both players and audiences as a golden age to be remembered with nostalgia. Harty was knighted in 1925 in recognition of his achievements both as composer and conductor.

In the early 1930s Harty’s good relations with the Hallé began to deteriorate, partly as a result of the constraints arising from the financial crash of October 1929 and its international consequences, partly as a result of Harty’s growing wish to be allowed more independence. In the summer of 1931 he made the first of his tours abroad as conductor, which took him to the United States for a series of concerts at the Hollywood Bowl in California. Though he remained under contract with the Hallé, this was in retrospect the start of a new phase in his career, that of a freelance travelling conductor. The success of his California tour led him to repeated visits to the United States in subsequent years. In 1932 he resumed his earlier association with the LSO, and in February of the following year 1933, on his return from another tour of the United States, he announced rather abruptly his resignation from the Hallé as from the end of the 1932-1933 season. He also indicated that he would be taking over the LSO as its permanent conductor (Ménestrel 21/3/1933). More tours to the United States followed in 1934, and in that same year Harty made his first (and in the event only) tour of Australia. In the meantime his relations with the LSO started to deteriorate; his wish for independence was once more the source of the friction, and his regular contract with the LSO terminated at the end of the 1934-1935 season. Early in 1935 he made his first appearance with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, one of many up to the end of his career. The orchestra had been formed by the BBC in 1930, and its foundation was followed in 1932 by the creation by Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent of yet another London orchestra, the London Philharmonic (LPO), with which Harty subsequently gave concerts and made a number of recordings. The days of the Hallé’s preeminence in British musical life were well and truly at an end.

In the meantime Harty’s health began to show signs of strain as a result of his heavy schedule and frequent travels. 1936 was the last year in which he was able to make tours abroad, and in the autumn he was diagnosed with a brain tumour. An operation led to the loss of sight in his right eye, and for the whole of 1937 and most of 1938 he was unable to conduct. He used the intervening period to resume composition, and in March and April of 1939 was able to conduct performances of his new works, the tone poem The Children of Lir and Five Irish Poems. But the outbreak of war with Germany (3 September 1939) curtailed musical activities in the country. In September 1940 Harty’s house in London was bombed, and now in failing health he had to move to Hove in Sussex, where he died on 19 February 1941.

Many years later, in 1975, Harty’s papers were donated to Queen’s University Belfast by his personal secretary Olive Baguley; she had formerly been secretary of the Hallé during his period as conductor, but moved to his personal service in 1933 when he resigned from the orchestra. The donation of his papers to Belfast University was an appropriate gesture, in view of his long association with Ulster, which the University acknowledged by conferring an honorary degree on him in July 1933. An inventory of his papers is available online on the University’s website.

Even before he took up his appointment as permanent conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in 1920, Harty was a dedicated champion of Berlioz. In his 1920 interview for The Musical Times he declared his intention to perform much of his music in Manchester, where he found audiences much more receptive to the composer than in London: ‘Berlioz is one of the gods of my idolatry … Berlioz and Mozart are my private deities … they are the two great intuitive composers as distinguished from the great logical ones’. Over the following years he went on to put his intentions into practice by treating audiences in Manchester and elsewhere to a feast of Berlioz such as Britain had not experienced since the days of Charles Hallé in Manchester. During the 1920s and early 1930s Harty and the Hallé became known at home and abroad as the leading exponents of Berlioz in the country (for his reputation in France see notably Le Ménestrel 17/9/1926, 4/5/1928, 12/4/1929, 10/1/1930).

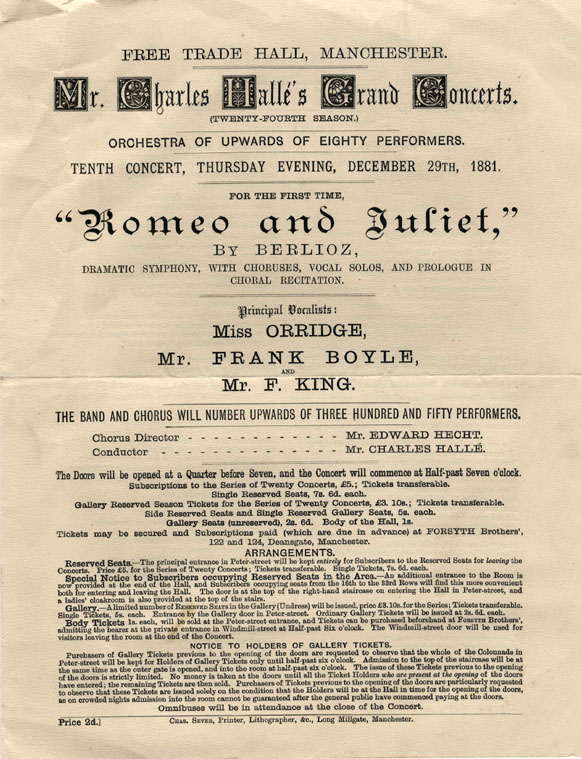

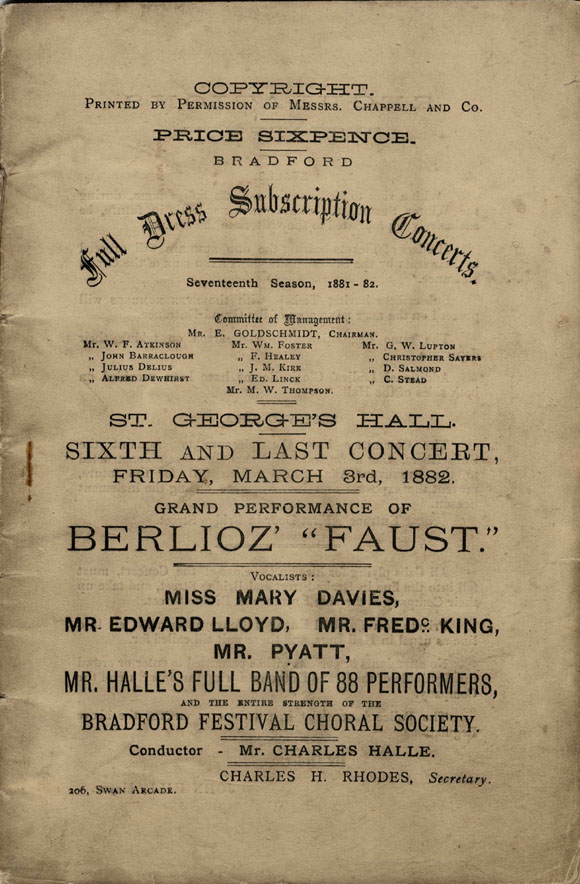

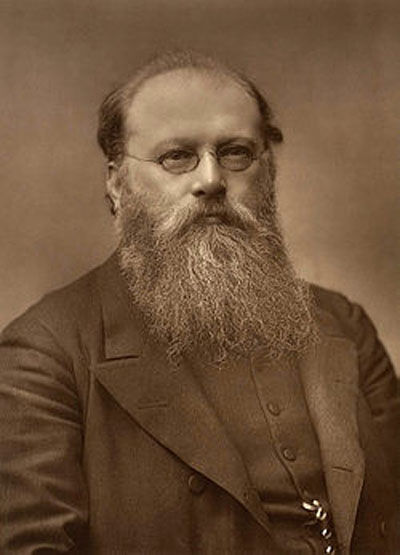

It was of course entirely appropriate that it should have been in Manchester that this should have happened, and with the Hallé Orchestra as its instrument: the orchestra was founded in 1857 by the German-born Charles Hallé (1819-1895 - portrait below), a close friend of Berlioz from the time of his stay in Paris from 1836 to 1848. The 1848 revolutions caused him to emigrate to England where he soon settled in Manchester and transformed the musical life of the city: ‘This energetic Teuton did more for music in the North of England than all the men who came before and after him put together’, as Beecham put it (A Mingled Chime [1944], ch. 4). As conductor of the orchestra he had founded, Hallé gave in Manchester the first performances of several of Berlioz’s major works: the Symphonie fantastique (9 January 1879), la Damnation de Faust (5 February 1880), l’Enfance du Christ (30 December 1880), and Roméo et Juliette (29 December 1881; see the programme below). Repeat performances of some of these works were given subsequently in neighbouring cities and in London: Hallé established the practice of taking his orchestra to London, despite the costs involved. See for example on this site a review of Faust in London in May 1880, a review of another performance of Faust in Manchester in January 1882, the programme below of Faust in Bradford on 3 March 1882, a review of another performance of Faust in London in 1892, and the comments added by Hallé’s son to his father’s Memoirs published in 1896. The Paris weekly Le Ménestrel reported several times on these Berlioz performances in Manchester and London, commenting on Hallé’s determination to champion the music of his friend, and his insistence on bringing his orchestra to London (Ménestrel 30/11/1890, 6/12/1891, 17/1/1892, 26/2/1893).

How far Harty was consciously following in the footsteps of Charles Hallé seems impossible to determine: Harty himself does not point to the connection, and he is in fact silent about when and how his enthusiasm for Berlioz first developed. It seems unlikely that his father’s collection of musical scores contained many of Berlioz’s works, which were probably difficult to obtain in Ireland at the time and were rarely if ever performed there. A local orchestra in Belfast is known to have put on two performances of Faust in 1896, but it is not known whether Harty attended or indeed participated in either of these (Dibble, pp. 10-11). It was probably only after he came to London that he would have had easier access to published scores of Berlioz, and the new Breitkopf and Härtel edition of his works only started to appear in 1900 (unlike France, it was freely available in Britain).

Hallé’s place as permanent conductor of the Manchester orchestra was eventually taken over by another German musician, Hans Richter (1843-1916 - portrait below), who was in charge in Manchester from 1899 to 1911 (cf. Ménestrel 23/10/1898). Richter is remembered in the first instance for his close connection with Wagner and the Bayreuth festival: he conducted the first performances of the Ring cycle in Bayreuth in 1876 and appeared there regularly for many years to come. Richter was known for his promotion of the German repertory, especially Beethoven, Wagner and Brahms, but despite his reported disdain for French music he made an exception for Berlioz. From the start of his appointment as conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic in 1875 he included music by the composer in his programmes. He soon became a frequent visitor to London and England, and gave some notable performances of major works by Berlioz there: the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale in 1885 (Wotton, Hector Berlioz ch. 7 p. 159), the Requiem at the Birmingham festival in 1888 (Ménestrel 22/7 and 23/9/1888), La Damnation de Faust in London in 1888 and 1889 (praised by Bernard Shaw, but criticised by Hans von Bülow), the Te Deum at the Birmingham festival in 1894 (Ménestrel 7/10/1894).

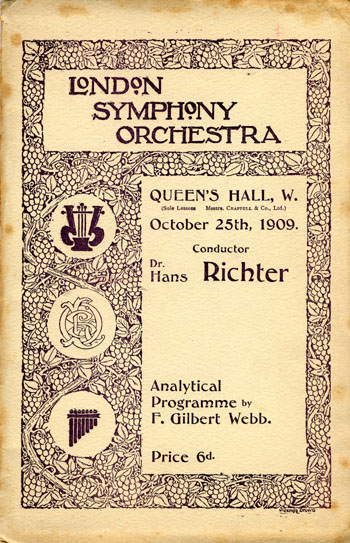

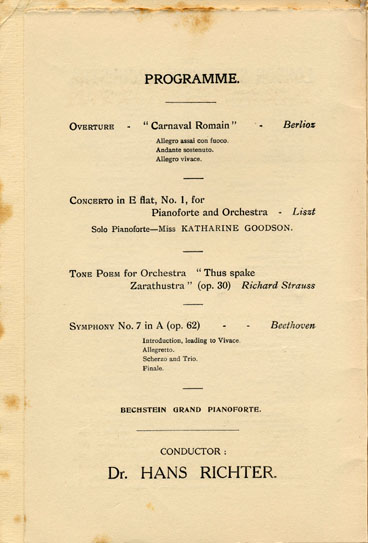

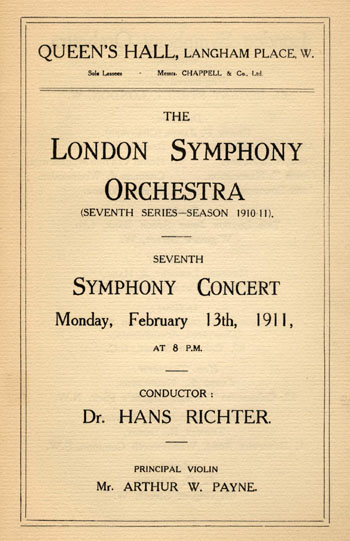

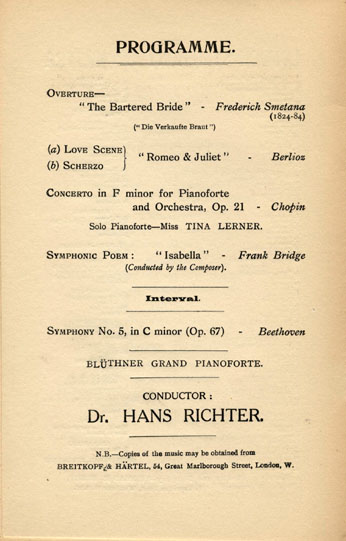

We have not been able to establish how far Richter included music by Berlioz in his Hallé concerts in Manchester or London (like Charles Hallé before, he took his orchestra to the capital, cf. Ménestrel 29/3/1903). At any rate Berlioz did figure at times in his London concerts with the recently-founded LSO, of which he was also conductor from 1904-1911. Two examples are the Carnaval romain overture on 25 October 1909 (see the concert programme below) and two orchestral movements of Roméo et Juliette on 13 February 1911 (see the concert programme below). He is also known to have conducted la Damnation de Faust at the Birmingham festival on 8 October 1909 (Ménestrel, 9/10/1909, p. 326). Whether Harty attended any of these or other Berlioz performances at the time is not known, though he will certainly have been aware of the celebrations in London in 1903 for the centenary of Berlioz’s birth. Characteristically, these involved primarily German conductors: Hans Richter himself (date not specified), Felix Weingartner on 12 November (Ménestrel 8/11, 15/11 and 22/11/1903) and Richard Strauss on 11 December (Ménestrel 6/9/1903), with only one event that is not known to have involved German musicians (Ménestrel 20/12/1903).

From the available evidence it seems that it was only after the outbreak of war in 1914 that Harty started to include music by Berlioz in his concerts, for the first time in 1915 (see the Table of performances below). Down to 1917 it was a matter of shorter pieces (overtures and orchestral excerpts), though one concert (10 March 1917) included the song Absence with Agnes Nicholls, which suggests that Harty’s years as accompanist may have given him opportunities to acquaint himself with the repertoire of Berlioz songs. In 1918 (8 October) he conducted in Manchester for the first time the complete Damnation de Faust; although this was in replacement of Thomas Beecham who was unavailable, it suggests that he was already then well acquainted with the work. Then in 1919 (which happened to be the 50th anniversary of Berlioz’s death in 1869) there was a noticeable increase in the number of Berlioz performances he gave in Manchester: he did for the first time a complete Symphonie fantastique (5 April) and another complete Damnation de Faust (22 November). Both works were evidently very well received and so were repeated before the end of the year (18 and 22 December). This must be what Harty is referring to when he mentioned in April 1920 how receptive Manchester audiences were to his conducting of Berlioz, which then encouraged him to continue in this direction as permanent conductor of the orchestra.

‘During the last nine or ten years most of Berlioz’s important works have been presented by me in Manchester’, wrote Harty in December 1928. The record largely bears this out, though with some qualifications. During his period in Manchester Harty performed at least once (and often more frequently) all the overtures with the exception of Waverley (and Rob Roy, but Berlioz himself had rejected that work). He also performed all four symphonies complete (as well as orchestral excerpts from Roméo et Juliette), La Damnation de Faust complete (as well as the 3 orchestral excerpts), the Requiem, the Te Deum, and gave a concert performance of Les Troyens à Carthage in 1928, as well as performing frequently the two orchestral pieces Chasse royale and the Marche troyenne derived from the complete work. (It should be mentioned that Les Troyens was sung in an English translation, which seems to have been Harty’s normal practice with all vocal works not in Latin).

A few significant gaps among works he might have been expected to promote may be noted. Surprisingly, he never gave L’Enfance du Christ, although it required only modest forces (fewer than La Damnation de Faust, for example). He was specially fond of one of its movements (Le Repos de la Sainte Famille), which he arranged as an instrumental piece for cello and piano and performed in his chamber concerts (Dibble p. 198 n. 42); he is known to have considered giving a performance of the complete work, though this did not materialise (letter of 20 December 1934, from the Harty papers in Belfast). The major gap in his repertoire were the operas. Harty had serious reservations about opera as an art form, and, unlike Beecham, his career as a conductor was almost entirely spent in the concert hall and not the opera house (he made brief appearances at Covent Garden in 1913). But he did give occasional concert performances in Manchester of several operas (for example Carmen). He gave one of Les Troyens à Carthage, but did not attempt La Prise de Troie nor Berlioz’s other two operas, Benvenuto Cellini and Béatrice et Bénédict, though he performed the overtures of the latter two frequently. There were rare performances of vocal excerpts from Cellini (1927), but none from Béatrice (though the duet of the two women at the end of Act I was a popular piece in concerts in Paris before the 1914 war). Nor did he perform Les Nuits d’été complete, and only occasionally two individual songs from the cycle (1917, 1930). With these qualifications, it remains true that Harty’s repertoire of Berlioz works was by the end of the 1920s more extensive than that of any other previous conductor in Britain, Charles Hallé not excepted.

Harty’s Berlioz repertoire was virtually complete even before the end of his period with the Hallé; thereafter it seems the only work he added was the funeral march for the last scene of Hamlet, but that was for a special occasion (a concert on 19 March 1934 commemorating the death of Elgar). The works he performed with various London orchestras from 1932 onwards came from his existing stock, and the same is true with his travels abroad (mostly to the United States). His Berlioz repertoire there consisted almost exclusively of shorter orchestral works that were likely to be popular, with the exception of a complete performance of the Symphonie fantastique in Rochester in 1935. On the other hand, Harty’s commitment to Berlioz in his post-Hallé period remained undiminished. He gave a notable broadcast performance of the Requiem and the Symphonie funèbre with the BBC orchestra on 4 March 1936, and after he had partially recovered from the illness which interrupted his conducting for nearly two years, he was still performing Berlioz symphonies in the early months of 1940 after the declaration of war.

In a lecture delivered in October 1931 at Liverpool University, Harty divided contemporary conductors into two categories (citation from Plummer pp. 376-7 and Dibble p. 215):

There are those whose only aim is to follow out what they conceive to be the composer’s meaning by the most faithful attention to every detail, and who try to keep from any display of their own emotional reactions to the music, and those others whose interpretations are a true reflection of the personal impressions they receive. Each school has its own followers. Personally, I lean rather towards the latter class, for the reason that I prefer something that is living even if it may sometimes be wrong, to something that is perfectly correct but lifeless.

The difference between the two approaches might be described for convenience as that between ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ approaches to musical performance. Among Harty’s contemporaries Toscanini would be an example of the ‘objective’, and Furtwängler one of the ‘subjective’ approach, but the difference goes back well before Harty’s time. It might be traced to Berlioz himself as opposed to Wagner, and one fundamental difference between them concerned their treatment of tempo. Berlioz insisted on regularity and consistency of tempo (but without any rigidity), whereas Wagner treated tempo with much greater freedom, which Berlioz explicitly disliked (cf. the letter CG no. 1991 of July 1855). It is not possible nowadays to make an independent judgement on the conducting styles of Berlioz and Wagner, and of other conductors of their time, but by the mid 1920s recording technology had progressed sufficiently to make it possible for later generations to form a direct impression of how Harty and other contemporary conductors approached the music they performed.

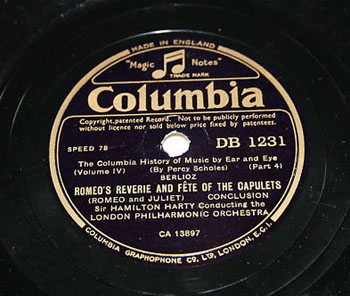

As regards the music of Berlioz, Harty recorded a small but significant number of his works. The following list has been compiled partly from reissues of the original recordings, and partly from the tables in Plummer (Table 11 following p. 180) and Dibble (pp. 309-10). Included are only the electrical recordings (Harty first recorded the Marche hongroise and Carnaval romain overture using the earlier acoustic method, but recorded them again later with the newer electrical technology). Abbreviations as in the Table of performances below.

| Date | Work | Orchestra | Company |

| 30 April 1927 | Marche hongroise | Hallé | Columbia |

| 30 April 1927 | Valse des Sylphes | Hallé | Columbia |

| 30 April 1927 | Roméo IV | Hallé | Columbia |

| 10 April 1931 | Chasse royale | Hallé | Columbia |

| 18 February 1932 | Carnaval | Hallé | Columbia |

| 7 & 9 September 1933 | Roméo II | LPO | Columbia |

| 9 November 1934 | Béatrice overture | LPO | Columbia |

| 9 November 1934 | Corsaire | LPO | Columbia |

| 26 April 1935 | Marche funèbre pour la dernière scène d’Hamlet | LPO | Columbia |

| 16 October 1935 | Lear | LSO | Decca |

| 16 October 1935 | Marche troyenne | LSO | Decca |

These represent of course only a small sample of Harty’s Berlioz repertoire. They are all purely orchestral pieces without any vocal music; in the recording of the Hamlet march the voiceless chorus is replaced by instruments, which unfortunately destroys an arresting effect in an otherwise deeply felt performance. They are also all shorter pieces (overtures or orchestral excerpts, but no complete symphony); in particular there is no recording of the Symphonie fantastique, the major work of Berlioz that Harty performed most frequently. Yet Harty did make recordings of complete symphonies (Mendelssohn’s Italian and Dvorak’s New World symphonies, among others), and Weingartner had made a recording of the Symphonie fantastique as early as October 1925. That recording was made by the Columbia company, to which Harty was also under contract at the time; it is conceivable that the company did not want to undercut itself by issuing a rival to one of its own very successful recordings.

It is sometimes difficult to assess objectively recordings made several generations ago: performing conventions and fashions change, and what is regarded as normal practice at one time may be considered later an outdated mannerism. For example, one noticeable feature of Harty’s recordings of Berlioz, made in the late 1920s and early 1930s, is the frequent use of portamento in string playing, notably in slow movements — the use of audible shifts of the left hand on the string when moving from one note to another, applied deliberately for expressive purposes. Examples are found in the slow introduction of Roméo II, of the Carnaval romain overture, and in the Valse des Sylphes from Faust. Nowadays this technique is avoided, unless specifically written in the score by the composer (for example sometimes by Mahler in his symphonies). In general, far more importance is now attached to ‘authenticity’: a premium is placed on using instruments and a style of instrumental playing that approximate to what was current in the composer’s time. Furthermore, the progress in techniques of recording and playback, which make it possible to replay instantly minute details in a recording, has probably affected the expectations of contemporary audiences and the way they listen to music. All of this would have seemed difficult to imagine at a time when the only way to experience music was to attend a live performance.

Taken as a whole, Harty’s recordings of Berlioz impress by their sincerity, conviction and vitality; they illustrate vividly Harty’s determination to bring the music to life and convey its spirit as he conceived it, even if they sometimes depart from the strict letter of what Berlioz wrote. Harty sometimes follows Berlioz’s metronome marks, and sometimes does not, and in general treats tempo more freely than Berlioz seems to have envisaged.

The recordings share common characteristics: one of them is expressive and eloquent slow movements, which time and again reveal Berlioz as the great melodist that he was. At times Harty adopts speeds slightly slower than those indicated by the composer, for example in the Andante introduction of the Carnaval romain overture (slower than crotchet = 52), the Adagio sostenuto of Le Corsaire (slower than quaver = 84), or the introductory Larghetto of the Chasse royale et orage (slower than crotchet = 76). He also makes frequent use of rubato in slow sections: for example in the Carnaval romain overture; in the Béatrice overture he begins the Andante un poco sostenuto at the marked crotchet = 52, but then slows down for the passage in string unison (beginning at bar 48), and returns to the original tempo after it.

Fast movements are invariably lively and exciting. Harty sometimes follows closely at the start the marked tempo, as in the Corsaire and Béatrice overtures or the Marche troyenne. In other cases he takes the movements faster that Berlioz indicates, notably the main Allegro of Roméo II (faster than minim = 108, which is already fast). He is liable to change the tempo while the music is in progress. In Carnaval romain there is an unmarked slowing down for the return of the music of the Andante during the Allegro assai (bar 304), with a return later to the original tempo. In Roméo IV (Queen Mab) he slows down for the passage with hunting horns (from bar 475, again, unmarked in the score), only to speed up again later. Another frequently recurring feature in the quick sections is Harty’s tendency to press on towards the end of the movement: thus in the Béatrice, Corsaire and Carnaval romain overtures, the Marche troyenne, and in Roméo II (excessively so in this case). The main section of Chasse royale starts slower than the marked Allegretto crotchet = 112 (as most performances do), but then is whipped up into a frenzy for the outbreak of the storm, faster than what is written; this is then followed by a considerable slowing down up to the end of the movement. In almost every case the performances come off, whatever the literal divergences from Berlioz’s score. The one disappointment is the recording of Marche hongroise, taken faster than Berlioz’s steady minim = 88, with the inevitable but unmarked and unnecessary accelerando towards the climax of the march. This (mis)reading of Berlioz’s piece seems to have developed in the late 19th century, when the march became a very popular concert piece (often at the end of concerts), and this way of performing it somehow hardened into a pernicious and lasting tradition (Colin Davis was one of the few conductors to play the piece simply as written by Berlioz, with considerably enhanced effect).

But with this one exception the Harty recordings of Berlioz remain fresh and vital to this day. The Béatrice overture might be singled out as particularly outstanding, a wonderfully youthful performance of great wit and delicacy. No wonder it was one of Harty’s favourite concert pieces. One can only regret that he did not live longer to provide a fuller record of his devotion to Berlioz.

![]()

Note. As seen above, Harty’s special affinity for the music of Berlioz was widely acknowledged in his day. It comes therefore as a surprise to note that one of the leading Berlioz scholars of the time, Tom S. Wotton, made no mention at all of Harty in his book on Berlioz published in 1935 (the full text of which is available on this site). Wotton mentions many other eminent conductors of his time, some of whom championed the music of Berlioz: among them Jules Pasdeloup, Hans von Bülow, Édouard Colonne, Artur Nikisch, Hans Richter, Arturo Toscanini, Thomas Beecham and Felix Weingartner, but not Hamilton Harty (see the Index to his book). Yet Wotton must have been aware of Harty and his activities, through Harty’s concerts, broadcasts and recordings, and through newspaper reports. He was himself a contributor, among other papers, to The Musical Times, which published in 1920 a detailed article on Harty (see the excerpts on this page). Wotton himself reported in The Musical Times on the 1928 symposium on Berlioz in which Harty participated, but without mentioning by name any of the contributors to the discussion (‘A Berlioz Conference’, Musical Times 1 April 1929, pp. 318-20). This paper is not mentioned in Wotton’s book and not listed in his bibliography, nor is the 1929 full publication of the symposium. It is difficult to explain or justify this silence of Wotton on one of the leading Berlioz champions of his day.

![]()

This provides only a skeleton outline of the most salient dates in Harty’s career. For a full and documented account of his life the reader is referred to the 2013 book by Dibble (see above).

4 December: Hamilton Herbert Harty born at Hillsborough, Co. Down

12 February: Harty appointed organist and choirmaster at Brookmount Parish Church, aged 14

21 November: Harty appointed organist at the church of St Barnabas in Belfast

20 March: performance in Belfast of La Damnation de Faust which Harty may have attended

6 November: Harty appointed organist at Christ Church, Bray, some 13 miles south of Dublin

Foundation in Dublin of An Ceis Feoil, an annual festival of Irish music with competitions in composition

7 and 8 March: concerts in Dublin by the Hallé Orchestra conducted by Frederic Cowen

15 and 16 November: concerts in Dublin by the Hallé Orchestra conducted by Hans Richter

Harty’s String Quartet no. 1 wins a prize at the Ceis Feoil

20 February: Harty leaves Dublin for London to begin a career as accompanist

Autumn: Harty meets the soprano Agnes Nicholls

23 September: first joint appearance of Harty and Agnes Nicholls

May: Harty conducts his Irish Symphony at the Feis Ceoil in Dublin, his first conducting experience; the symphony is awarded the prize

15 July: Harty marries the soprano Agnes Nichols

18 April: Harty conducts again his Irish Symphony in Dublin

October 1905 to January 1906: tour of the USA and Canada with the violinist Marie Hall

5 April: first concert of Harty as conductor, with the British Symphony Orchestra at Queen’s Hall, London

25 September: Harty conducts the first performance of his Ode to a Nightingale at the Cardiff festival, with Agnes Nicholls singing

May-June: Harty participates in Birmingham’s Promenade Concerts

23 September: Harty conducts the first performance of his symphonic poem With the Wild Geese at the Cardiff festival

20 March: at the invitation of Hans Richter, Harty conducts his With the Wild Geese with the LSO at Queen’s Hall, London

9 May: Harty invited by Hans Richter to conduct a complete concert with the LSO

6 March: first appearance of Harty with the Hallé Orchestra

2 October: Harty conducts the first performance of The Mystic Trumpeter at the Leeds festival

9 November: Harty’s first appearance conducting opera (Tristan and Isolde at Covent Garden)

29 November: Harty conducts Carmen at Covent Garden

23 April: Harty conducts the Hallé Orchestra at Westmoreland in The Mystic Trumpeter

4 August: Britain declares war on Germany

28 January: concert with the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, the first in a series during the war

June: Harty starts a period as volunteer for service in the Royal Navy, and is stationed at Aberdour in Fife

22 May: Harty is discharged from the Navy on health grounds

1 November: death of Harty’s father

11 November: armistice to end the war

January: with the recommendation of Thomas Beecham, Harty is appointed permanent conductor of the Hallé Orchestra starting with the 1920-1921 season

1 April: article on Hamilton Harty in The Musical Times

14 October: first of the regular Hallé concerts conducted by Harty in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester

15 March: Harty plays his own Piano Concerto at a Hallé concert conducted by Thomas Beecham

January: concerts with the Hallé in Dublin and Belfast

June: Harty receives a knighthood (Ménestrel 19/6/1925)

28 January: first Berlioz broadcast by the Hallé (Symphonie fantastique)

19 February: death of Harty’s mentor Michele Esposito in Italy

June-August: first visit as conductor to the United States, concerts at Boston (20 June), in California at the Woodland Theatre (6-11 July), and the Hollywood Bowl (14-25 July) (cf. Ménestrel 19/6, 17/7, 14/8 and 18/9/1931)

19 February: Harty conducts the LSO in London for the first time since 1920 (cf. Ménestrel 18/3/1932)

April: trip to Spain for a single concert with the Madrid Philharmonic Orchestra

June-July: trip to the United States, concerts in California at the Woodland Theatreand the Hollywood Bowl (Ménestrel 29/7/1932)

November: trip to Belgium for one concert; start of a series of 6 concerts with the LSO in the 1932-1933 season

January-February: visit to the United States, concerts with the Cleveland Orchestra (5, 7, 12, 14 January) and with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra

5 February: Harty resigns from the Hallé from the end of the season

23 March: last concert by Harty with the Hallé in Manchester

July: Belfast University confers an honorary degree on Harty

July-August: visit to the United States, concerts at the Hollywood Bowl and Chicago (Ménestrel 25/8/1933)

Autumn: start of a series of 8 concerts with the LSO in the 1933-1934 season

January-February: visit to the United States, concerts in Chicago (9, 11, 12 January) and Rochester (19 and 25 January, 8 February)

April: travel to Australia

May-June: concerts in Australia in Melbourne (19, 23, 26, 30 May) and Sidney (9, 13, 16, 20, 22 June)

July: travel from Sidney to California

July-August: in the United States, concerts at the Hollywood Bowl (24, 26, 28, 31 July and 2, 4 August), then Chicago (12-24 August) (Ménestrel 3/8/1934)

September: return to England

Autumn: 4 concerts with the LSO in the 1934-1935 season

29 December: departure for the United States

January-February: visit to the United States, concerts in Rochester (10-21 January) and Chicago (24 and 25 January)

Late February-early March: first appearance of Harty with the BBC SO

January-February: Harty’s last visit to the United States, concerts in Chicago (23, 24, 28 January) and Rochester (30 January, 12 February)

2 March: Harty gives a talk on Berlioz at the BBC as a prelude to a broadcast concert on 4 March of the Requiem and the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale (Ménestrel 13/3/1936)

October: Harty is diagnosed with a brain tumour, and loses his right eye as the result of an operation

December: Harty unable through illness to conduct a performance of Roméo et Juliette

—

23 December: studio broadcast concert with the BBC SO, Harty’s first concert since October 1936

1 March: first public appearance since 1936 in a concert at Queen’s Hall with the BBC SO, first performance of his new work The Children of Lir (Ménestrel 18/3/1939)

8 April: broadcast performance of Five Irish Poems

Harty begins writing his autobiography, but it remains an unfinished sketch of his early years up to his move to London

February: participation in the Bournemouth Festival which takes place from 25 February to 3 March (cf. Ménestrel 8/3/1940)

September: Harty’s house in London bombed; he moves to Hove on the Sussex coast

1 December:

Harty’s last concert, with the BBC SO at Tunbridge Wells

19 February: death of Hamilton Harty

![]()

The following table has been compiled for the most part from the invaluable tables provided by Declan Plummer in his 2011 thesis (see above), notably Table 7 (after p. 110, Harty’s conducting during the war), Table 8 (after p. 131, Harty’s conducting after the war), Table 9 (after p. 134, Harty’s post-war engagements with the Hallé), and Appendix I pp. 450-537: The Hallé Concerts, 1920-1933. A few supplementary items have been added from Dibble’s 2013 book (see again above), to which specific references have been made (but unlike, for example, the book by Kenneth Birkin, Hans von Bülow. A Life for Music [Cambridge, 2011], Dibble does not provide a listing of the concerts given by Harty such as Birkin provides for Hans von Bülow in his Appendix pp. 387-699, and he does not mention the work of Plummer). It should be added that the listing below is certainly not complete and may contain errors (Plummer does not cover systematically the post-Hallé period of Harty’s conducting career).

Abbreviations of works by Berlioz: Béatrice = Béatrice et Bénédict, Benvenuto = Benvenuto Cellini, Carnaval = overture le Carnaval romain, Chasse royale = Chasse royale et orage from Les Troyens, Corsaire = overture le Corsaire, Damnation = la Damnation de Faust, Fantastique = Symphonie fantastique, Francs-Juges = overture les Francs-Juges, Harold = Harold en Italie, Invitation = Invitation to the Dance (Weber, orch. Berlioz), Lear = Le Roi Lear overture, Marche hongroise = from Damnation, Menuet = Menuet des Follets from Damnation, Roméo = Roméo et Juliette, Roméo II = Roméo seul. Tristesse. Concert et Bal. Grande fête chez Capulet, Roméo III = Scène d’amour, Roméo IV = La reine Mab, ou la fée des songes, Valse = Valse des Sylphes from Damnation.

Note also:

BBC SO = BBC Symphony Orchestra

Hallé = Hallé Orchestra

LPO = London Philharmonic Orchestra

LSO = London Symphony Orchestra

| Date | Work | Orchestra and/or venue | Notes |

| 1915 | |||

| 15 February | Carnaval | Hallé, Manchester, Midland Hall | Dibble p. 119 |

| 27 February | Marche hongroise | Hallé, Manchester Promenade Concerts | Dibble p. 118 |

| 30 October | Cellini overture | Hallé, Manchester Promenade Concerts | |

| 13 November | Carnaval | Hallé, Manchester Promenade Concerts | |

| 1916 | |||

| 11 January | Roméo IV | Birmingham Orchestral Concerts | |

| 1917 | |||

| 5 February | Cellini overture | LSO, Queen’s Hall London | |

| 5 March | Carnaval | LSO, Queen’s Hall London | |

| 10 March | Cellini overture, Absence (Agnes Nicholls) | Hallé, Manchester Promenade Concerts | |

| 1918 | |||

| 23 February | Béatrice overture | Hallé, Regular Series | |

| 2 October | Carnaval | Hallé, Manchester Promenade Concerts | |

| 8 October | Damnation complete | Hallé, Manchester Promenade Concerts | Dibble p. 154 n. 53; replacing Beecham |

| 8 November | Béatrice overture | LSO, Wigmore Hall London | |

| 7 December | Carnaval | Hallé, Regular Series | |

| 1919 | |||

| 4 March | Cellini overture | LSO, Queen’s Hall London | |

| 22 March | Marguerite’s romance from Damnation (Gladys Ancrum) | Hallé, Regular Series | |

| 5 April | Fantastique | Hallé, Regular Series | Dibble p. 136-7 |

| 15 May | Roméo IV | LSO, Queen’s Hall London | |

| 18 October | Marche hongroise | Leeds Orchestral Concerts | |

| 19 October | Marche hongroise | LSO, London Palladium | |

| 22 November | Damnation complete | Hallé, Regular Series | |

| 30 November | Marche hongroise, Menuet, Valse | LSO, London Palladium | |

| 7 December | Cellini overture | LSO, London Palladium | |

| 11 December | Cellini overture | Hallé, Regular Series | |

| 18 December | Fantastique | Hallé, Regular Series | Dibble p. 140 |

| 22 December | Damnation complete | Manchester | Dibble p. 139 |

| 28 December | Invitation | LSO, London Palladium | |

| 1920 | |||

| 8 February | Carnaval | LSO, London Palladium | |

| 15 February | Corsaire | LSO, London Palladium | |

| 25 March | Menuet, Valse, Marche hongroise | Hallé, Regular Series | |

| 28 October | Béatrice overture | Hallé | |

| 25 November | Damnation complete | Hallé | |

| 3 December | Béatrice overture | LSO, Queen’s Hall London | |

| 4 December | Cellini overture | Hallé | |

| 1921 | |||

| 17 February | Fantastique | Hallé | |

| 3 November | Menuet, Valse, Marche hongroise | Hallé | |

| 1922 | |||

| 12 January | Carnaval | Hallé | |

| 9 February | Béatrice overture | Hallé | |

| 16 February | Corsaire | Hallé | |

| 9 March | Chasse royale | Hallé | |

| 19 October | Fantastique | Hallé | |

| 2 November | Te Deum | Hallé | |

| 23 November | Lear | Hallé | |

| 1923 | |||

| 11 January | Roméo IV | Hallé | |

| 13 January | Marche hongroise | Hallé | |

| 15 February | Harold, Chasse royale | Hallé | |

| 15 March | Chasse royale, Marche hongroise | Hallé | Concert conducted by Beecham with Harty as soloist in his own Piano Concerto |

| 22 March | Roméo IV | Hallé | |

| 8 November | Chasse royale | Hallé | |

| 13 December | Symphonie funèbre et triomphale | Hallé | First performance in Manchester; performed without chorus in the last movement |

| 1924 | |||

| 10 January | Cellini overture | Hallé | |

| 24 January | Corsaire | Hallé | |

| [February] | Damnation complete | Hallé, Albert Hall, London | Ménestrel 22/2/1924 |

| 28 February | Carnaval | Hallé | |

| 9 April | Unspecified | Hallé | Broadcast of concert from Central Hall, London; Dibble p. 174 |

| 6 November | Damnation complete | Hallé | |

| 11 November | Carnaval | Hallé, Queen’s Hall London | Ménestrel 14/11/1924; Dibble p. 177 |

| 13 November | Béatrice overture | Hallé | |

| 25 November | Fantastique | Hallé, Queen’s Hall London | Dibble p. 177 |

| 1925 | |||

| 12 February | Carnaval | Hallé | |

| 19 March | Carnaval | Hallé | |

| 5 November | Lear | Hallé | |

| 12 November | Requiem | Hallé | First performance in Manchester; Dibble p. 185 |

| 3 December | Chasse royale | Hallé | |

| 1926 | |||

| 28 January | Fantastique | Hallé | First Berlioz work to be broadcast by the Hallé |

| 4 March | Béatrice overture | Hallé | |

| 18 March | Cellini overture | Hallé | |

| 21 October | Marche troyenne | Hallé | |

| 8 November | Damnation complete | Hallé, Municipal Concert | |

| 11 November | Requiem, Roméo III and IV, Marche hongroise | Hallé | Armistice Day Concert; Dibble p. 185 |

| 22 November | Carnaval | Hallé, Municipal Concert | |

| 16 December | Francs-Juges overture | Hallé | |

| 1927 | |||

| 13 January | Carnaval | Hallé | |

| 20 January | Requiem | Hallé, Albert Hall, London | Broadcast at request of BBC; Ménestrel 11/2/1927; Dibble p. 185-6 |

| 17 February | Harold | Hallé | |

| 3 March | Corsaire | Hallé | |

| 7 November | Mais qu’ai-je donc? aria from Cellini (Annie Packman) | Hallé, Municipal Concert | |

| 17 November | Chasse royale | Hallé | |

| 1 December | Roméo complete | Hallé | The concert was broadcast |

| 5 December | Cellini overture | Hallé, Municipal Concert | |

| 1928 | |||

| 9 February | Cellini overture | Hallé | |

| 23 March | Fantastique | Hallé, in London | Ménestrel 6/4/1928, 4/5/1928; Dibble p. 191 |

| 1 November | Les Troyens à Carthage (concert performance) | Hallé | The concert was broadcast See the review by Richard Capell |

| 10 December | Marche hongroise | Hallé, Municipal Concert | |

| 13 December | Roméo III, IV, II | Hallé | |

| 1929 | |||

| 17 January | Corsaire | Hallé | |

| 4 February | Carnaval | Hallé, Municipal Concert | |

| 1 March | Damnation complete | Hallé, London | The concert was broadcast; Ménestrel 12/4/1929; Dibble p. 198 |

| 21 March | Valse, Menuet, Marche hongroise | Hallé, Pension Fund Concert | |

| 14 November | Cellini overture | Hallé | |

| 28 November | Corsaire | Hallé | |

| 12 December | Roméo III, IV, II; Béatrice overture | Hallé | |

| 1930 | |||

| 20 January | Carnaval, Chasse royale | Hallé, Municipal Concert | |

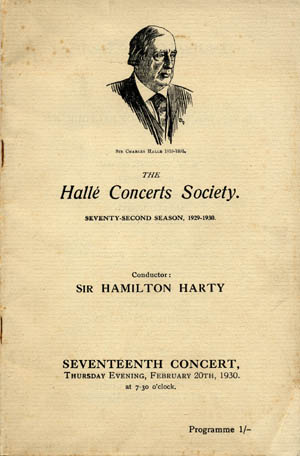

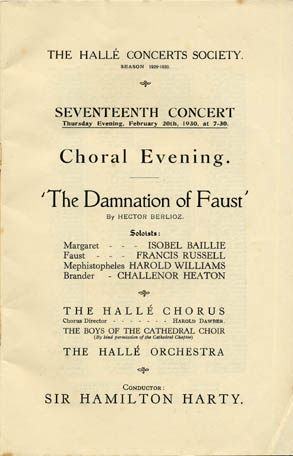

| 20 February | Damnation complete | Hallé | Parts I, II, III broadcast; see programme below |

| 27 February | Béatrice overture | Hallé | |

| 20 March | Carnaval | Hallé, Pension Fund Concert | |

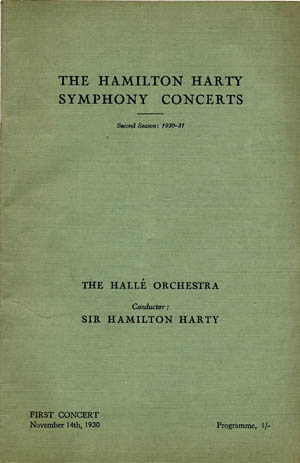

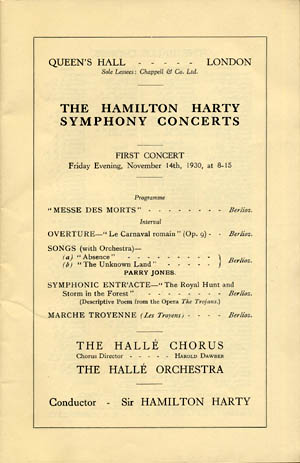

| 13 November | Requiem, Carnaval, Absence and L’Île inconnue (Parry Jones), Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | Hallé | All Berlioz concert; Ménestrel 28/11/1930; Dibble p. 207-9 |

| 14 November | Same programme as 13 November | Hallé, Queen’s Hall London | See programme below; Dibble p. 207-9 |

| 1931 | |||

| 5 February | Fantastique | Hallé | Ménestrel 20/2/1931 |

| July | Carnaval | Hollywood Bowl Concerts with Los Angeles PO | Cf. Ménestrel 19/6, 14/8 and 18/9/1931 |

| 21 July | Cellini overture | Hollywood Bowl Concerts with Los Angeles PO | |

| 25 July | (?) Chasse royale, Marche troyenne | Hollywood Bowl Concerts with Los Angeles PO | |

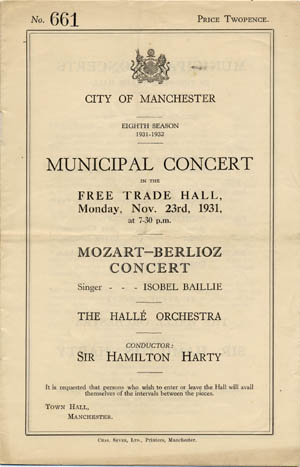

| 23 November | Fantastique II and IV; Absence and L’Île inconnue (Isobel Baillie); Valse, Menuet and Marche hongroise; Carnaval | Hallé, Municipal Concert | Mozart-Berlioz concert; see programme below |

| 3 December | Béatrice overture | Hallé | |

| 1932 | |||

| 14 January | Harold (Lionel Tertis, viola) | Hallé | Dibble p. 212 |

| 15 February | Carnaval | LSO, London | |

| 29 February | Béatrice overture, Roméo IV | LSO, London | |

| 3 March | Roméo IV | ? | |

| 10 November | Fantastique | ? | The concert was broadcast |

| 1933 | |||

| 12 and/or 14 January | Chasse royale | Cleveland Orchestra, Cleveland (Ohio) | Dibble p. 223 |

| 9 March | Corsaire | Hallé | The concert was broadcast |

| 29 July | Carnaval | Hollywood Bowl Concerts | |

| 3 August | Cellini overture | Hollywood Bowl Concerts | |

| 6 August | Marche hongroise | Hollywood Bowl Concerts | |

| 4 December | Unspecified | LSO, London | Dibble p. 225 |

| 1934 | |||

| 11 and 12 January | Corsaire | Chicago SO, Chicago | |

| 19 or 25 January or 8 February | Béatrice overture | Rochester PO, Rochester (NY) | |

| 19 March | Marche funèbre pour la dernière scène d’Hamlet | LSO, London | Concert in memory of Elgar; Dibble p. 227 |

| May | Valse, Marche hongroise | Melbourne, Australia | |

| Between 24 July and 4 August | Marche hongroise, Valse, Menuet, Marche troyenne, Carnaval | Hollywood Bowl Concerts | Cf. Ménestrel 3/8/1934 |

| 22 November | Béatrice overture | LPO, London | Dibble p. 242-3 |

| 3 December | Unspecified | LSO, London | Dibble p. 245 |

| 1935 | |||

| 10 January | Chasse royale | Rochester PO, Rochester (NY) | |

| 17 January | Fantastique | Rochester PO, Rochester (NY) | |

| 24 & 25 January | Béatrice overture | Chicago SO, Chicago | |

| End February-early March | Unspecified | BBC SO, London | Dibble p. 247 |

| 8 April | Harold (Lionel Tertis, viola) | LSO, London | Barzun, Berlioz and the Romantic Century I (1950), p. 248; Dibble p. 247 |

| October | Chasse royale | Torquay, with municipal band | Dibble p. 250 |

| 1936 | |||

| January/February | Roméo II and IV | Chicago or Rochester | |

| 4 March | Requiem, Symphonie funèbre et triomphale | BBC SO, Queen’s Hall, London | The concert was broadcast; cf. Ménestrel 13/3/1936; Musical Courier, 28 March 1936; Barzun, Berlioz and the Romantic Century I (1950), pp. 354-5; Dibble pp. 255-8 |

| 1937 | |||

| — | |||

| 1938 | |||

| — | |||

| 1939 | |||

| — | |||

| 1940 | |||

| 14 February | Harold (Lionel Tertis, viola) | BBC SO, Bristol | Dibble p. 289 |

| Late March | Fantastique | BBC SO, Bristol | Dibble p. 289 |

![]()

Early in 1920 it was announced that the Hallé Orchestra had appointed Hamilton Harty to be its permanent conductor starting in autumn 1920; this appointment put an end to the succession of temporary guest-conductors, one of whom was Harty himself, who had been in charge of the Hallé since the outbreak of war in 1914. In the event Harty was to hold this post for over a decade down to 1933. On the occasion of his appointment Harty gave an interview to The Musical Times in which he talked about himself, his earlier career, his musical likes and dislikes, and what he proposed to achieve with the Hallé. The interview appeared in The Musical Times (vol. 61 no. 926, pp. 227-30) on 1 April 1920. Excerpts from this interview are reproduced below. On Harty and Berlioz see also the page Hamilton Harty on Berlioz.

![]()

[...] I was brought up on international music, on Anglican Church services, and the classical chamber writers. I am sorry I can’t bring folk-music into the story. Such little folk-music as there used to be in my native County Down was not Irish, but Scottish. Music in my early impressions did not mean fiddle at fairs or immemorial drinking-songs in taverns, or indeed anything more Bohemian or more picturesque than my father’s organ-playing (he was organist at the Episcopal Church at Hillsborough, where I was born), and chamber music at home, where my mother led the family string quartet. I can recall hearing as a small child the sonatas of Mozart and Beethoven being played every night downstairs as I lay falling to sleep. At the age of nine I was organist and choirmaster at Brookmount, near by, my father helping me with the choir.

He was a born musician — self-taught, and an unbeliever in academic teaching. Anyone, according to him, could learn to play a musical instrument if he had the will and a hand-book to point to the rudiments. And, upon my word, I won’t say I think he was wrong, though his was not the way to produce virtuosos. The use of a modicum of technique for him was a key wherewith to enter the delightful pastures and still waters of the classics. He set me on that way, and as a small boy I could play all “The Forty-Eight” of Bach by heart. And later on a similar procedure served me well enough in matters such as orchestration. What more does one want for that than a collection of scores to see how it is done and the chance to hear on an orchestra how it sounds. A booklet may be useful to tell you that flutes can’t play below C or violins below G. I have never had a lesson in orchestration

The worst of life in Ireland is that there are practically no orchestras. I was sixteen and organist at Bray, just outside Dublin, before I fell in with any sort of orchestral music. Previously to this I had served a term as organist at St. Barnabas, Belfast. At Dublin I was admitted into the local orchestra as a violist, and a very inferior violist I was, but the orchestra itself was not superlative. This music-making set me writing overtures and things, and a symphony was successful at the Feis Ceoil. And at Dublin I fell willingly captive to Dr. Michele Esposito.

This Italian musician is the presiding genius of all that there is of music in Ireland. As an all-round musician he is, I should say, unsurpassed in Europe. I send him for criticism everything I write, and put as implicit faith in him now as when a boy — he has always been right. One of the jokes between us, however, has always been his refusal when I first asked him to give me pianoforte lessons: “You will never play the pianoforte,” he said, “your thumbs are too short”.

As a pianoforte teacher he is marvellous. His pianoforte class at the Royal Irish Academy of Music is worthy of comparison with those of the biggest centres. Such polish! such beautiful tone!

Why don’t we, then, hear something of young Irish musicians over here?

Well, the Irish musical student is greatly facile, and still more greatly indolent. He reaches a certain point and then drifts. Ireland offers him no scope: yet, as a rule, he is reluctant to leave home. That did not hold good with me. At twenty I came over here. I worked at accompanying, and enthrallingly interesting I found it, with such a variety of music does one thus become acquainted, and with such a variety of artists — little and big, but all human. I wrote for the festivals, — “Ode to a Nightingale” for Cardiff, “The Mystic Trumpeter” for Leeds. I married. I conducted the London Symphony Orchestra.

[...] The “Hallé” is the alertest of bands. Its wind is the most beautiful in the country, and the leader, Mr Catterall, I hold to be the best of our native violinists. Inevitably the Orchestra suffered during the war, and as much as anything from being pulled first this way, then that, by incessant changes of conductors. Of course I shall not be going to them as a stranger. I have no apprehensions, for though I know that there is no possible bluffing of such a first-rate orchestra, and no bullying, they can be got to do anything if one will explain himself quietly and rationally.

In my work I shall come in touch too with various choral societies, and here a thorny problem exists which to my mind has hardly been satisfactorily handled in the past. The problem concerns the relations of the choirmaster who trains the singers and the conductor who directs the public performance. If the performance of the larger and more modern choral works are to be brought nearer adequacy, the conductor must in future have more say in the preparation of the choir.

One of the pleasures of the musician at Manchester is in the subtlety of the audiences there. Yes, they are not only keen but also subtle. The difference is immense between them and Londoners, who so often seem to be listening with closed minds. A London audience is often simply not to be won, but sits in apathy as much as to say that as a sufficient impression of such and such a composer, or such and such a work had been formed years ago, no fresh one is desirable. I should despair of charming London with Berlioz in the way in which Manchester has lately been charmed. This leaning of theirs towards Berlioz suits me, because Berlioz is one of the gods of my idolatry. We shall be having quite a lot of Berlioz at Manchester next winter — the “Fantastic” again, and “The Damnation of Faust” complete, “Harold in Italy”, and portions of his opera “The Trojans”.

Berlioz and Mozart are my private deities. I cannot always make people see what ground they have in common, yet it is clear to me that they are the two great intuitive composers as distinguished from the great logical ones. Of course all great composers must have intuition, but most have had to eke theirs out with logic, while intuition hardly ever seems to have failed my two heroes. And it is intuition that I count as the supreme thing in music. Call it heart as against head if you will. In Berlioz, as in Mozart, you are always coming upon a beautiful, fresh-sprung musical line such as no amount of head-work could have suggested. In Wagner, much as I love his music, I feel sometimes a mechanical process at work which makes me rate him below Berlioz.

This logic that can go on for ever, though intuition fail, is the source of all the dull, pretentious music of the ancients and of the terrible cleverness of the moderns. But I think the modern logicians have the better of it, because they are not so preternaturally solemn. Logic if tolerable must tend towards comedy, and such composers as Stravinsky and Ravel (whom I admire greatly) are all that is witty. Save us from the composers who argue solemnly!

[...] Opera seems to me a form of art in which clumsy attempts are made at defining the indefinable suggestions of music. Or else one in which the author of a plot and his actors are hampered by music which prolongs their gestures and actions to absurdity and obscures the sense of their words. The sound apologia for opera is on the lines that it induces into listening to music many people who are not musical enough to love it for its own sake without the accessories of operatic acting and operatic scenery — such as they are! Is it possible to-day not to see that Wagner deluded himself when he thought he was making a new and supreme harmony out of half a dozen arts? When we hear Wagnerian opera we put up with a lot — for the sake of the music. Who for instance wants actually to see Isolda waving her scarf in signal to Tristan? The music is telling us of that, and also of the fluttering of Isolda’s heart. The action here is as superfluous as that objectionable habit of some people at concerts when they start humming on recognizing a favourite theme. Sometimes Wagner’s staginess tends to make ridiculous scenes which, left to the music, would be amply significant.

[...] Operatic scenery affects me similarly. The Prelude to Act 3 of “Tristan” has painted the sea so well that it is always a descent to be shown the scenic artist’s attempt at it a minute or two later. The subject might be run to earth in those operas where music is at its most grandiose, and the scene precipitates itself from the merely banal into something near the grotesque. The last scene of “The Twilight of the Gods” is a classic example.

[...] My ideal at Manchester will be to have no music played simply because it is new — or because old — or because it is familiar or because not, or just because it was composed in England or in Jugo-Slavia, or in the Isle of Man. I hope to arrange programmes based on worth. I do not believe in too great a proportion of a concert being in strange, novel idioms. I hope to have something new at each concert, and also at each a solid proportion of music that can be enjoyed without the learning of a new language each week.

But before all that happens, I am counting on a summer in the country, and a chance to put down on paper some of the music out of my own heart — or head.

![]()

All the concert programmes reproduced below come from our own collection.

On Charles Hallé see above.

On Hans Richter see above. Richter was highly regarded internationally in his day; for a different view of his abilities it might be worth quoting the verdict of Beecham (A Mingled Chime [1944], chapter 6):

In those days [after his appointment to the Hallé] he enjoyed a commanding prestige which owed more to his personal association with Richard Wagner than to a talent which had decided limitations. A few things he interpreted admirably, a great many more indifferently, and the rest worse than any other conductor of eminence I have ever known. But his readings of Beethoven and Wagner were considered sacrosanct, and from them there was no right of appeal.

This recording of the second movement of Roméo et Juliette was made on 7 & 9 September 1933.

This concert was one of the Regular Series of Hallé concerts which took place on Thursday evenings at 7.30 pm in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester.

This was one of the many concerts given by the Hallé at Queen’s Hall in London.

This was one of the series of Municipal Concerts which took place on Monday evenings at 7.30 pm in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester. The concerts were subsidised by the City of Manchester and aimed at a more popular audience. The first part of this concert was devoted to Mozart, and comprised the overture to The Magic Flute, the aria Dove sono from The Marriage of Figaro (sung by Isobel Baillie), the Symphony in G minor (no. 40), and the overture to The Marriage of Figaro. All vocal pieces, the aria by Mozart and the excerpts from Les Nuits d’été (in the second part of the programme), were sung in English translation, as was normal at the Hallé concerts.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir

Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997;

Page Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions created on 15 March 2012; this page created on 1st August 2019.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.