![]()

|

|

|

This page is also available in French

See also:

Letters of the composer’s family at the Hector Berlioz Museum (includes 122 letters of Adèle Suat, 4 of Marc Suat, 10 of Joséphine Suat, and 17 of Nancy Suat)

![]()

Berlioz made a number of visits to the historic city of Vienne near Lyon, always for family reasons: his younger sister Adèle and her family lived there. In 1839 Adèle had married Marc Suat, a lawyer from Saint-Chamond, and they had two children, Joséphine and Nancy (whom Berlioz called Nanci). In 1845 the family moved to Vienne, where they lived in an apartment; they also had a very elegant country house in Estressin near Vienne.

Adèle was Berlioz’s favourite sister; she always supported him and accepted him for who he was. She was more than just a younger sister, rather, as he said, ‘a close friend’. She was the only member of the family who did not raise any objections to her brother’s desire to marry an actress, Harriet Smithson. After their marriage, she would correspond with Harriet as well as her brother. Berlioz’s only child Louis was born on 15 August 1834 in Montmartre; when he was christened on 23 August of the following year it was to Adèle that Berlioz broke the news in a letter dated 23 September (Correspondance générale, no. 409, hereafter abbreviated CG):

[…] For a start, rest assured, our boy has been baptised. His name is not Hercules, Jean-Baptiste, Caesar, Alexander, or Magloire, but simply Louis […] The boy is charming, very strong, with superb blue eyes, a tiny dimple on the chin, rather fiery blond hair as I had when a child, a little pointed cartilage on the ears as I have, and the lower part of the face somewhat short. So much for the similarities with his father, but unfortunately he does not have any of his mother’s features. Harriet is absolutely mad about him. […]

Adèle was one of the few members of his family to visit Berlioz in Paris – she and her husband went there in May 1839 on their wedding trip and Berlioz showed them around and took them to have tea with Alfred de Vigny (CG nos. 651, 709).

The affection Berlioz felt for his younger sister extended also to Adèle’s two daughters; Berlioz was closer to them than he was to his other sister Nanci’s daughter Mathilde, and it was to them that he dedicated the first part of L’Enfance du Christ. He was similarly closer to Marc Suat than to Nanci’s husband, Camille Pal.

Adèle’s death of a heart-related illness at the age of 45 early in March 1860 came as a terrible blow to Berlioz, as he wrote to his friend Auguste Morel on 9 March (CG no. 2487):

I had good news today, but the news I received three days ago was terrible. Your work has just scored a brilliant success and ... my sister has died.

We loved each other like two twins. She was a close friend. Last week I had made the journey to Vienne to see her once more, and I left with the assurance given by a celebrated doctor in Lyon that her convalescence was about to begin.

I cannot convey to you the heartbreak this loss causes me. […] Louis is in Vienne with his cousins and his uncle. He has had to endure on his own the burden of all this terrible pain. […]

The next time Berlioz went to Vienne was in 1864 (from 4 to 18 September), as he recalls in the last section of his Memoirs:

The following week my son had to depart, as his leave was coming to an end. — I felt gripped with a keen desire to see again Vienne, Grenoble, and especially Meylan, my nieces and… someone else [Estelle Fornier], if only I could find her address. I left. My brother-in-law Marc Suat and his two daughters, whom I had informed the day before, came to meet me at the railway station in Vienne, and soon took me to Estressin, a neighbourhood not far from the city, where every summer they spend three or four months. It was a great joy for these charming children, one of whom is nineteen and the other twenty, though the joy was somewhat sullied when on entering the drawing-room of the house in Vienne I noticed the portrait of their mother, my sister Adèle who had died four years before. My surprise was deep and grievous, and to them and their father it was a painful shock to witness this. The room, the furniture, and the portrait had long been before their eyes, day after day; familiarity had sadly blunted the sharp edge of their memories, and time had done its work… Poor Adèle! what a warm heart! she was so completely forgiving and so gentle for the asperities of my temperament, and even for my most childish caprices!… One morning, on my return from Italy [in 1832], we were in a family gathering at La Côte Saint-André; it was pouring with rain, and I said to my sister:

— Adèle, would you like to go for a walk?

— By all means, dear friend; wait till I put on my clogs.

— Look at those two lunatics, said my elder sister; as they say, they are capable of going to splash around in the countryside in this kind of weather.And indeed I took a large umbrella, and, ignoring their mocking comments, Adèle and I went down to the plain where we walked for nearly two leagues, huddled together under the umbrella, without saying a word. We loved each other.

I spent a fairly quiet fortnight with my nieces and their father in the seclusion of Estressin.

Adèle’s husband died in 1869 and was buried in the same tomb as his wife in Vienne’s historic Cimetière du Pipet.

After Adèle’s death Berlioz continued his close relationship with Marc Suat and his two nieces; he corresponded with them frequently and made occasional visits to Vienne; in 1861 he invited them to attend one of the concerts he was giving every year in Baden-Baden (CG nos. 2562, 2575).

Berlioz’s closeness to his nieces may be illustrated by one of his many letters to Joséphine and Nancy, dated 9 December 1865 (CG no. 3071; NOTE: the French original is full of puns that are untranslatable in English):

I like that! That is how you treat your uncle! You leave him for three or four weeks without writing one word! not a single word! Yes, on the subject of sincerity, I have never believed you to be guilty. But I have no idea what you are embroidering, what you are engraving, nor what is happening on the Place de la Halle, nor what is being said in your drawing-room, nor what you are practising on the piano with four hands, nor how is your father, nor what you are reading, nor the temperature on the barometer of boredom, nor what Victoire is cooking for you, nor anything.

Ah! the nieces of today cannot compare with those of the past, those of the good old days. For I do belong to the good old days, and I take pride in the fact. I must be made of stern stuff to have withstood over so many years so many painful blows, so much exertion, so many lies of every kind… For you will know, dear nieces, charming snipes, beloved rascals, that the day after tomorrow is the 11th of December, and that is the day when I will have the misfortune of being sixty-two years old, and you will not have written me a single line to wish me a happy birthday. I will have been the first to embrace you, just when you were least expecting it, and I will have got in ahead of you… It is true that I asked you once and for all never to send me any letter of greetings for my birthday or for the New Year. They mean nothing more to me than the toasts I receive at banquets where you have to gulp down speeches. Those are my prejudices. Everyone has theirs. I detest conventional customs and habits. So I thank you in all seriousness for not have written to me for my birthday, because I find that silly. […] So I embrace you in a tender, violent, fatherly, friendly, poetical way, or even more, in a musical manner. I have no pain this evening, so I am taking advantage of this lull to write to you; anything I write tomorrow will be excruciating, and once my pain returns my heart will be as dry as a piece of old wood….. good evening, Joséphine, good evening, Nanci, give me your four hands, since you have four hands, and your four cheeks, and your four eyes. Good, I send you my gentlest blessings. But I know very well that like Robert Macaire you will say: ‘How good that uncle is at giving his blessing!’

Are you still frightened of cholera? It has been very sluggish this time round. There is still a terrible number of rascals and fools around it could have freed us from. But be patient! you have to take people as they are, and cholera for what it is worth.

Louis is in Mexico, as is Emperor Maximilian, and I am sure it is not Louis who has the most worries on his mind.

Farewell my pretty nieces, my hearts of gold, my diamonds without straw! When I think I am able to say: MY! And yet it is true!

H. BERLIOZ

Berlioz’s last visit to Vienne was in 1867, from around 11 August to 14 September. He had been invited to attend Joséphine Suat’s wedding to Marc Antoine Auguste Chapot, an officer in the French army. Berlioz was one of the witnesses at the marriage which took place on 10 September (CG no. 3271, note 1). While Berlioz was in Vienne he took the opportunity to make two short visits to Estelle Fornier (CG nos. 3270-71) who at the time lived with her son Henri and his family at Saint-Symphorien d’Ozon (CG no. 3232, note 1); the second visit, on 9 September, was the last time that Berlioz saw her.

Adèle’s other daughter Nancy married Gilbert de Colonjon. Though she died childless there is a direct line of descent from Adèle through Joséphine’s second son Victor Chapot to our own time in the person of Abbé Robert Chapot, who in 1981 donated numerous letters and other family documents from Adèle’s side of the family to the Musée Hector Berlioz. His nephew, the great-great-grandson of Adèle, is M. Alain Rousselon, formerly president of the Association nationale Hector Berlioz.

![]()

All the photographs reproduced on this page were taken by Michel Austin in 2009 and Pepijn van Doesburg in 2003. The 1840 engraving and the 20th century postcards are from our own collection. © Pepijn van Doesburg; Michel Austin and Monir Tayeb. All rights of reproduction reserved.

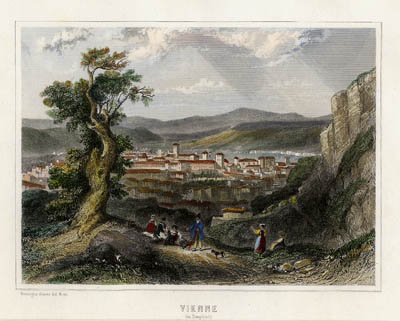

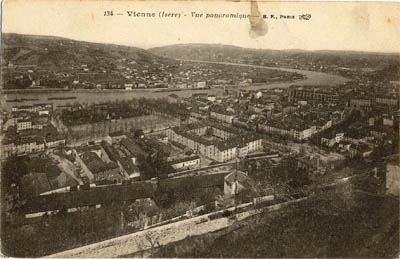

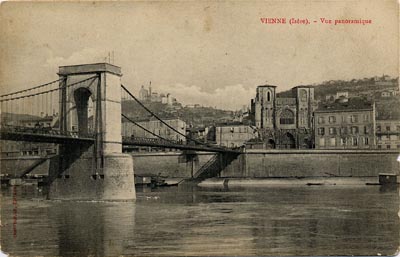

1. General views of Vienne

Vienne ca. 1840

General view of Vienne in 1912

General view of Vienne in the early 20th century

The cathedral, Cathédrale Saint-Maurice, is across the Rhône to the right of the bridge. The hill to the left of the cathedral is Mont Pipet.

A view of Vienne in 1912

The postcard shows Cours Romestang (on the side of the railway station).

The tomb of Adèle and Marc Suat in 2009

The tomb of Adèle and Marc Suat in 2009

This is the original headstone; the larger and fresher stone installed behind it, with a different text, was clearly added later.

The tomb of Adèle and Marc Suat in 2009

The text on the tomb reads:

ICI REPOSENT/ ADELE SUAT/ NÉE BERLIOZ/ DÉCÉDÉE/ LE 2

MARS 1860/ A L’AGE DE 46 ANS

MARC SUAT/ DÉCÉDÉ/ LE [- - -] 1869/ A L’AGE DE 70 ANS/

DE PROFUNDIS

[HERE REST/ ADELE SUAT/ BORN BERLIOZ/ DIED/ ON 2 MARCH 1860/ AT

THE AGE OF 46]

[MARC SUAT/ DIED ON [day and month illegible] 1869/ AT THE AGE OF 70 YEARS/

DE PROFUNDIS]

Note: the date given on the tomb for the death of Adèle, 2 March 1860, has generally been accepted, yet it raises difficulties. As kindly pointed out to us by Peter Bloom, the official register of deaths of the city of Vienne records Adèle’s death as having taken place at 6 in the morning on the 6th of March, and the entry in the records was made at 10 in the morning of the same day. It seems very unlikely that this official record could be wrong, but it is also hard to understand how the family of Adèle could have allowed the date of 2 March to be engraved on the tombstone and allowed to stand if it had been wrong. A further difficulty is raised by the letter of Berlioz cited above. Berlioz states that he received the news of his sister’s death three days earlier, and he himself gives the 9th of March as the date of the letter. Assuming this date is correct, does Berlioz mean that he heard the news on the 6th of the month (counting exclusively), or the 7th (counting inclusively)? It would be perfectly possible for a letter posted to Berlioz on the day of Adèle’s death in Vienne to reach Paris the following day, but it is most unlikely that the news of Adèle’s death could have reached Berlioz on the day when she died.![]()

The tomb of Adèle and Marc Suat in 2009

The text reads:

DE PROFUNDIS

The tomb of Adèle and Marc Suat in 2009

The text reads:

ICI REPOSENT UNE SŒUR UN BEAU FRERE DE H. BERLIOZ

[HERE REST A SISTER A BROTHER-IN-LAW OF H. BERLIOZ]

Cimetière du Pipet in 2009

This photo shows the start of Ally H, where the tomb of Adèle and her husband is located (on the right).

Cimetière du Pipet in 2009

This is the view from Ally H running down hill towards the main entrance of the cemetery.

Cimetière du Pipet in 2009

The hill on the horizon to the right of the photo is Mont Salomon, with the ruins of the château de la Bâtie on top. The château was built in the 13th century by Jean de Bernin, one of the grand archbishops of Vienne. That is all that has survived from the city’s mediaeval fortifications.

Cimetière du Pipet in 2009

![]()

The tomb of Adèle and Marc Suat in 2003

The tomb of Adèle and Marc Suat in 2003

We are most grateful to our friend Pepijn van Doesburg who kindly sent us the 2003 photos.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel

Austin on 18 July 1997;

Berlioz in Vienne was created on 4 May 2004 and enlarged on 1st November 2009.

© (unless otherwise stated) Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

Copyright notice: The texts, photos, images and musical scores on all pages of this site are covered by UK Law and International Law. All rights of publication or reproduction of this material in any form, including Web page use, are reserved. Their use without our explicit permission is illegal.