Introducing Benvenuto Cellini

by

David Cairns

© Gramophone

|

Introducing Benvenuto Celliniby David Cairns © Gramophone |

|

WHEN I wrote in the November 1968 issue about Philips’s plan to record a Berlioz cycle, I mentioned Romeo and Juliet— then on the point of release—and The Trojans, which was soon to be recorded for the first time, and I said that we were thinking of a new Te Deum and a Damnation of Faust, a Requiem which had the benefit of a really spacious cathedral acoustic, and a Nuits d’été with three or four different voices as the score specifies. Apart from the Damnation (due to be recorded shortly), all these intentions have been realised. But the curious thing about that airing of our plans as they stood in 1968 is that it made no mention of the work whose recording we feel to be in some ways the most exciting achievement of the cycle to date—Benvenuto Cellini, recorded during last July and released here this month.

Why Benvenuto didn’t enter into our calculations I don’t know. I suppose that, although we realised we would be recording it one day, our thoughts were taken up with the works which Colin Davis was currently conducting and which it was logical to record first. In addition, the vast undertaking of The Trojans gave us more than enough to deal with without thinking of other Berlioz opera recordings; the special problems that Benvenuto Cellini presented—which of the different ‘versions’ to choose and where to find the right cast— would have to wait.

Once The Trojans was safely launched, we could start thinking of Cellini. Indeed, the enormous success of The Trojans both in prestige and sales—seven or eight top international prizes, many thousand sets sold in America alone—put us very much in the mood to do so.

The long business of planning an opera recording was even more protracted than usual in this case. First there was the question of the cast. It proved impossible to tie the recording to a revival at Covent Garden, so we started from scratch and could choose whatever singers were available. We all felt that for a French comedy a predominantly native cast was essential. The one major exception was not really an exception at all. Nicolai Gedda, who had already made the title role his own, is an honorary Frenchman, and we were delighted as well as fortunate to get him.

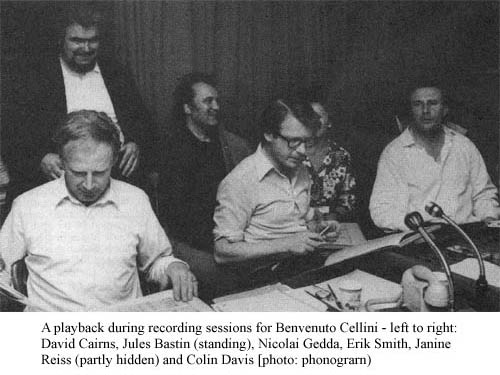

For the rest, although there is a widely held and pessimistic belief in this country that there are no good French singers, I hope this recording will help to show how groundless that belief is (allowing that the definition French includes French-speaking countries like Belgium and Switzerland). Erik Smith (Phonogram Classical Manager) and I went to Paris to see what we could find, and listened to various singers who had been marshalled for us at the Philips studio in rue des Dames by the kind offices of Elizabeth Hermann of Phonogram, Paris. We returned with some tapes under our arm, and in the succeeding months more tapes crossed the Channel. When we had enough evidence, we presented it to Colin Davis, then we discussed it together and made our choice. As it happened, only one member of the cast (the splendid bass Jules Bastin who sings the part of Balducci, the bumbling Papal treasurer), had been quite unknown to us before. Both Jane Berbié (Ascanio) and Hugues Cuenod (the Innkeeper) were familiar figures at Glyndebourne and the Promenade concerts; Robert Massard (Fieramosca) had appeared in several French roles at Covent Garden; Roger Soyer (Pope Clement VII) was a distinguished name in France and Germany and had taken part in the recording of The Trojans and Christiane Eda-Pierre (Teresa), although yet to sing in England, was the toast of the Wexford Festival. In short, as we discovered, the French singers are there if you look for them.

Once we had our cast—to which were added two important elements, Maurits Sillem, the moving spirit of the Covent Garden Cellini, and Janine Reiss, language coach, musician and diplomat extraordinary—we had to decide what we were going to give them to sing.

The great question of ‘which version’ of a work is to be preferred is largely a discovery of modern musicology. Our age loves to reopen a case formerly thought closed and to see the composer as having been forced against his own artistic judgement to compromise with the taste of the times. The theory is that if one can resurrect the work as it was before the musical establishment of the day got its hands on it, one will have the composer’s thought in its pure, uncorrupted essence. At its worst, this principle can have very dubious results; but it is certainly justifiable in individual cases (Bruckner’s symphonies, for example). Benvenuto Cellini is surely one such case.

We began, however, by thinking that we would base ourselves on the later or Weimar score, the version which, though partly emanating from Liszt, was adopted by Berlioz and published with his approval, and which has formed the text of almost all subsequent performances. But the more we studied the earlier, pre-Weimar material unearthed by Covent Garden for its performances in 1966 and 1969, the more convinced we became that the original, Paris version was the one to go for. One can see why Berlioz settled for the Weimar form of the work, which is a cut and re-arranged version of the original. It was less long; and it posed fewer technical problems. The Germans at that date liked their operas short (Wagner had been forced to chop Rienzi in half and give it on two successive evenings). And although the revised Benvenuto remained a formidably exacting work for orchestra, chorus, soloists and conductor alike, the Paris version of 15 years earlier had been even more difficult. In preparing the score for performances over which he knew he would have no direct control, Berlioz removed or simplified many of its more extreme virtuoso demands. Later on when Liszt, the work’s great champion and instigator of its revival, proposed his changes, there were strong psychological and practical motives for Berlioz’s accepting the situation as a virtual fait accompli. He felt himself, with intense gratitude, to be in Liszt’s hands. In Paris the work had failed, in circumstances which it must have still pained him to recall. In Weimar the work was a success; Germany was where its future seemed to be.

The booklet which accompanies the recording gives our reasons for regarding the case as still open, and presents the detailed arguments for the version that we chose to record. In such instances, of course, a modern recording company setting out to record a war-scarred nineteenth-century opera is in a more advantageous position than the embattled composer struggling to secure a good performance of a score technically far ahead of its time. In saying this I am not presuming to claim that we necessarily made the right decision in every case where we had to choose between two or three different forms of a given passage. At the very least, however, by deciding to record most of the original we have given wider currency to some highly characteristic music that it would have been a great pity to forego.

But I believe the recording does more than that: it proves the superiority of the Paris sequence of scenes in the final act and also the fundamentally opéra-comique nature of the work as Berlioz conceived it. Admittedly the Paris sequence has the drawback that it includes a fair amount of action originally designed to be spoken and not conducive to musical treatment; when the libretto, having been turned down by the Opéra-Comique, was accepted by the Opéra (where spoken dialogue was forbidden), most of this section was set, without great conviction, as recitative (it was this section that led Liszt to instigate his cuts). But we have been able to get round the disadvantage by following Covent Garden’s example and resorting to spoken dialogue, as was Berlioz’s original (and his final) intention. This is a great gain, for in every other way the Paris sequence of the last act is preferable: it makes much more sense of the action, it avoids the awkwardnesses and confusions of the Weimar reordered sequence, and it restores some delightful music which is musically and dramatically relevant and which we would be the poorer without. Benvenuto Cellini emerges, in this form, a better shaped dramatic entity and at the same time an even more brilliant and vital score than in the form in which it has been generally known.

How significant is the result? When you have been involved in the recording of an opera, it is not easy to appraise the stature of the music dispassionately. Benvenuto is no flawless masterpiece, nor a work of deep profundity. It is not an earlier Meistersinger. (Though it treats the theme of the artist in society, it does so quite lightly and obliquely, as part of a general evocation of the teeming, tumultuous life of Renaissance Italy.) But it is a work of astonishing, almost reckless invention, a work crammed with dazzling and touching things, huge and animated canvases and the most delicate translucent beauty. It shows a mixture of audacity and passionate craftsmanship worthy of its central character. For combined panache, wit, range of colour, atmospheric power and appetite for life it has few equals in nineteenth-century opera.

We may marvel that such a score could come out of the Paris of the 1830s, but it would be rash to suppose that the passing of time has removed its difficulties. Benvenuto Cellini is without doubt the hardest work, technically speaking, that we have tackled in the Berlioz cycle. The problem simply of getting everything to happen precisely together—so vital to the effect of Berlioz’s music, as of Mozart’s— and at the same time with the colour and élan required, is made constantly hazardous by the combination of virtuoso orchestral and vocal (including choral) writing with a rhythmic style in which you never know what is going to happen next. I am sure it is this factor, more than any other, that has prevented the work from establishing itself in the regular operatic repertoire. Even in the recording studio it makes ferocious demands on everybody’s skill and concentration. But the rewards are correspondingly great.

It is intoxicating music, if one can get it right. I have never known recording sessions so full of a sense of excitement and camaraderie. From the first rehearsals (which acquired an extra eventfulness for being filmed by a team from French television), there was an atmosphere of commitment. The challenge of the music put everyone on their mettle. At the same time its exuberance and sheer fun induced an almost holiday mood. Those who attended the Prom performance given a few days after the sessions will know what I mean. It was an evening of unforgettable enjoyment and adventure; and the records, I believe, have captured the same spirit.

_________________________

David Cairns was formerly a member of the Classical Artists Bureau of Phonogram International B.V. In addition to being the Music Critic of the New Statesman he is also on the Editorial Committee of the New Berlioz Edition.

![]()

*

We have transcribed the text of this article from the Gramophone

magazine of March 1973, a copy of which is in our collection. We are most grateful to David Cairns

and to the Gramophone magazine for granting us permission to reproduce the article on this page. A copy of the original article is also in the archive section of the Gramophone’s website.

![]()

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 1 April 2012.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights reserved.

![]() Back to Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions

Back to Berlioz: Pioneers and Champions

![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Berlioz: Pionniers et Partisans

Retour à la page Berlioz: Pionniers et Partisans

![]() Retour à la page Contributions originales à ce site et autres articles

Retour à la page Contributions originales à ce site et autres articles

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil