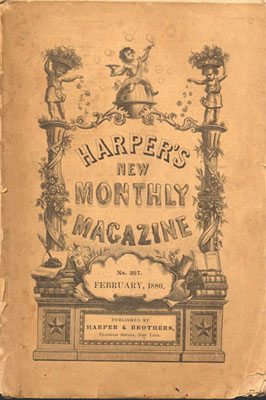

published in

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

No. 357 February 1880, pp. 411-417![]()

HECTOR BERLIOZ

NO art, no philosophy, no religion, can claim an example of more thorough devotion to an ideal than that which music possessed in Hector Berlioz ; in his genius, his character, his career, he was altogether remarkable, and no less so is the place he occupies in the history and development of music. His genius was unique, his character heroic, his life a tragedy. He had written the Symphonie Fantastique while Liszt was yet occupied with his amazing piano-forte transcriptions, and Wagner was looking to Meyerbeer as his model. “Art has its martyrs,” says Blaze de Bury, “its forerunners crying in the wilderness, and feeding upon roots. It has also its spoiled children sated with dainties.” One man braves the derision of an old world to discover a new, and wins poverty and chains ; another follows and gives his name to a continent. And Berlioz has seemed in danger of being lost among his very followers—outstripped, as it were, by the results of an impulse which he had himself given.

Hector Berlioz was born on the 11th of December, 1803, at Côte-Saint-André, a small country town nearly midway between Grenoble and Lyons. His father, Louis Berlioz, was a physician of excellent local repute, and of more than ordinary attainments. He was his son’s instructor in all the branches of a liberal education, not excepting the elements of music. At twelve the boy could sing at sight, and play the flute concertos of Drouet, at that time in vogue. He now unearthed an old copy of Rameau’s Harmony, but the treatise of the old French theorist has served but to mystify many maturer heads. It was by listening attentively to Pleyel’s quartettes as they were played by a club of amateurs that he became enlightened ; and soon after an original quintette appeared, which was successfully played by the club.

But an immense treatise on osteology, with life-size illustrations, was opened in the study, and grimly awaited the homage of the young student. The elder Berlioz intended his son for his own honorable profession : music he regarded as a graceful adjunct to a solid education. Not so the son. In his father’s own library he had read of Gluck and Haydn ; by chance, too, he had seen a score for grand orchestra. “Become a physician !” he cried ; “study anatomy ! dissect ! take part in horrible operations ! No, no. That would be a total reversion of the natural course of my life.” But the love, respect, and fear inspired by his father carried him through the course of study prescribed at home, and at eighteen he was ordered to join the army of medical students in Paris. He burned his quintettes, and departed.

Therefore in the year 1822 we find him in the Latin Quarter. His introduction to the dissecting-room of La Pitié had not been auspicious ; at the first sight of the place the new student had leaped from the window and run to his lodgings, where for twenty-four hours he lay in an agony of despair. Rallying, he had grappled bravely with a fate from which there seemed no escape ; and in process of time he was, to use his own words, in a fair way to add one more to the list of bad physicians, when, like any other medical student in Paris, he went to the opera. He heard the Danaïdes of Salieri, all in that splendor and completeness that distinguished the Grand Opéra of the Académie Royale. He was then tempted into the library of the Conservatoire, where he learned by heart the scores of Gluck. Finally, on coming out one night from a representation of Iphigenia,he vowed a vow that he would be a musician, “father, mother, uncles, aunts, grandfather, and grandmother to the contrary notwithstanding ;” and La Pitié saw him no more.

He set to work at once on a cantata with orchestral accompaniment, which composition gained him admission to the class of Lesueur. Meanwhile impassioned appeals went from Paris to Côte-Saint-André. The proud and upright old provincial physician was in mortal fear lest his son should become lost in the crowd of commonplace artists ; the mother believed in the infernal tendency of all art. The argument might be closed at any time by the unanswerable point of withdrawing the allowance. At last it came, and the youth found himself abandoned in the great capital. But he had joined the class of Reicha at the Conservatoire, and was engaged on the score of an opera—the Francs-Juges. A mass of his had already been performed in the church St. Roch, gained some attention from musicians, and favorable mention in one or two journals. He slept in a garret, and ate his dinner of bread and grapes sitting on the terrace of the Pont Neuf. As winter came on, cold and hunger might have made an end of the matter had he not secured a place in the chorus of the Théâtre des Nouveautés.

But the worshipper of Gluck and Spontini had little taste for the comic opera, and when in the course of a few months a remittance came from the relenting father, he abandoned the boards, and turned anew to the study of the classical drama. The evenings at the Grand Opéra were solemnities for which he prepared himself by study and meditation. Thither he was accustomed to lead a band of students and amateurs, range them at an early hour upon seats chosen and often paid for by himself, read and explain both libretto and score, comment upon cast and orchestra, and leave nothing undone to incite an admiration equal with his own. He would abide no liberties with the score, and did not hesitate to publish his indignation. “No cymbals there !” “Where are the trombones ?” “Who has taken it upon him to revise Gluck ?” rang an imperious voice above the tumult of chorus and orchestra. In purely orchestral music he had not hitherto been specially interested. That sublime enigma the Choral Symphony had already been propounded in London before the Heroic was brought out by Habeneck, leader of the Conservatoire orchestra (1828). Although in England there was a pretty wide opinion that Beethoven had exceeded the legitimate bounds of musical art, and many called upon the “revered shades of Purcell and Gibbons to witness and deplore the obstreperous roarings of modern frenzy,” still disapproval was much less marked than in the French capital. “Bizarre, incoherent, diffuse, bristling with rough modulations and wild harmonies, destitute of melody, forced in expression, noisy, and fearfully difficult”—such was the indictment. Even sturdy Habeneck was forced to some erasures. The violinist to whom had been dedicated the sonata that will save his name from oblivion—Kreutzer—declared it all “outrageously unintelligible,” and fled with his hands to his ears. But to Berlioz it was an inspiration.

Now at the summit of exaltation, now plunged in despair ; through struggle, privation, disappointment ; through all manner of torments incident to his condition or inseparable from his temperament—Berlioz lived to behold the year 1830, when he presented to the Institute his cantata Sardanapalus, and gained the Prix de Rome. This honor signified an annuity of 3000 francs for a period of five years, and two years’ residence in Italy. Before the laureate’s departure his newly finished Symphonie Fantastique was heard at the Conservatoire ; and then, while Paris was ringing with the clash of hostile and friendly criticism, he took his way toward the Eternal City.

The pensioners of the Academy of France inhabited the Villa Medici ; the director at that time was the illustrious Horace Vernet. Berlioz has left a strong protest against the custom that sent him to Rome. In the name of Palestrina he hastened to St. Peter’s. Of the music he speaks with the bitterness of disappointment. At the theatres he found it no better orchestra, dramatic unity, and common-sense were as nothing before the claims of vocal display. The very word symphony was unknown, except to designate a certain noise before the rising of the curtain, and to which nobody paid any attention. The names of Weber and Beethoven had scarcely been heard ; Mozart was mentioned by a worthy abbot of exceptional information as a young man of great promise ! We know the changes that have come with a new Italy ; that fine orchestral concerts have become frequent in Rome ; and that the Milan orchestra at the recent Exposition surprised all by its masterly performance no less than by its choice repertory, in which was Berlioz’s own Carnaval Romain. But the young French composer in Italy fifty years ago pined like an eagle caged. Leaving the director’s receptions, where he was exasperated by insipid cavatinas, the students’ revels, in which he sometimes joined with desperate hilarity, he went out to gaze at the moon through the rifts of the Coliseum, or to sit the night through in the garden of the Academy, while the owls cried from the desolate fields of the Villa Borghese. Père la Joie was the sobriquet soon bestowed by his ironical comrades. He was a victim of the subtle maladie d’isolement known to over-imaginative natures, and of which he has made a marvellous diagnosis in a chapter of the Mémoires. At the end of the year, being required to present something before the Institute as an index of his progress, he sent on a fragment of his mass heard years before at St. Roch, in which the learned members found “the evidences of material advancement, and the total abandonment of his former reprehensible tendencies.” Set free six months before the expiration of his time by a special act of the director, again we find him in the cosmos of Paris.

While yet a pupil at the Conservatoire (professor also of the guitar in a boarding-school), Berlioz had seen Hamlet as it was played for the first time in Paris by an English company, the star of which was the gifted Harriet Smithson. She it was who inspired Delacroix in his picture of Ophelia, who incited the poets, intoxicated the critics, and secured at once the success of the Shakspearean drama, for which the way had been prepared by the new school of littérateurs. The student’s steps turned every night toward the Odéon, where there had opened for him a new world, of which the lovely interpreter formed the only objective reality. After a night of enchantment, cast again upon the barren shore of every-day existence, he let go all earthly aims, and wandered to and fro as reckless of meat and drink as a disembodied soul, thinking ever of her who was the reconciling bond between the ideal and the actual, but from whom he was separated by all the distance that lies between glory and obscurity. Suddenly he astonished Cherubini by boldly asking for the hall of the Conservatoire, and still further by obtaining it in the face of his refusal. Miss Smithson should learn that he too was an artist. Copyists, orchestra, chorus, soloists were engaged, and the concert took place, with the usual amount of anxiety and inordinate expectation. But what effect on Miss Smithson ? No mention of Berlioz or his concert had reached her ears.

Now, on his return to Paris, he learned that Miss Smithson had also just arrived after a long absence, being about to undertake the direction of an English theatre. Chance secured her presence at the performance of that remarkable work of the composer’s An Episode in the Life of an Artist, which, in fact, is the story of his love, the first part being the Symphonie Fantastique, the second the lyrical monologue called Lélio. Next day a formal introduction took place, and in the summer of 1833 the two artists were married. The young directress had in the mean time learned the uncertainty of public favor. The name of Shakspeare was no longer an infallible passport ; the wave of romanticism had ebbed into a turbid pool, in which native dramatists disported themselves. The pæans were unsounded, the exchequer unfilled. Diana brought a swarm of creditors, and Endymion had no expectations.

A professorship at the Conservatoire was naturally looked for, and would have been of incalculable benefit to the composer at this juncture, saved him from journalism, and given him an official status in his guild. But between him and Cherubini there had always been an antagonism, even from the time when the irascible director had driven the unknown youth from the library for having entered by the wrong door ; and now the composer of Anacreon had no favors for heretics. The post of librarian was all the alma mater ever granted Hector Berlioz. Forced, therefore, to the precarious business of occasional concerts, to revising proofs, and miscellaneous tasks, he accepted the place of critic on the Journal des Débats — a labor destined to embitter his life.

The early opera of the Francs-Juges survives only in its vigorous overture ; but Berlioz had completed his Benvenuto Cellini, and in 1838 he contrived to get it upon the stage of the Opéra. He was none the less regarded as a lunatic by the director, Duponchel ; and the company was indifferent to a work whose failure was already deemed un fait accompli. The failure took place, and it was brilliant and complete ; it came at a critical time, and with crushing weight upon the composer. But Berlioz had not failed to attract devoted friends. The veteran Spontini held him in affectionate admiration ; young Liszt had visited him on hearing the Symphowie Fantastique ; and Paganini, after a performance of Harold in Italy, had knelt and kissed the composer’s hand in the concert-room. After the failure of Benvenuto Cellini, Berlioz found himself in dire straits. Ill in bed, he received a note from Paganini ; it contained a check for twenty thousand francs. Berlioz immediately planned the dramatic symphony of Romeo and Juliet — the inspired production of gratitude, a freed imagination, and blessed repose.

In 1841 [in fact 1842-3] Berlioz made an extensive tour in Germany, of which he has given details in a series of brilliant letters addressed to Liszt, Heine, and others. “I came to Germany,” said he, “as the men of ancient Greece went to the oracle at Delphi, and the response was in the highest degree encouraging.” At Leipsic he exchanged batons with Mendelssohn, though that favored son of art and fortune had no very warm sympathy with the French composer. Schumann, prophet as well as bard, had hailed him afar off. "For myself,” he wrote, “Berlioz is as clear as the blue sky above. I really think there is a new time in music coming.”

But in France again, and he is a writer of

feuilletons—“the sole object,” says he, bitterly, “for which

the Parisians imagine I am in the world.” One feels inclined to pardon the

Parisians, in view of those admirable specimens of French prose left by the

composer. He has all the French wit, more than French humor ; he narrates

with a keen eye to dramatic points; catches with wondrous skill the subtleties

of emotional experience. He might have been a great dramatist. In

his Mémoires![]() he has

forestalled the biographers as completely as did Benvenuto Cellini. His critical

papers are usually as just as they are eloquent. No man of equal creative genius

has been able to analyze so clearly, judge so fairly, and admire so fervidly the

music of others. Yet this literary labor was a source of great misery to a man

whose soul yearned toward another field of activity.

he has

forestalled the biographers as completely as did Benvenuto Cellini. His critical

papers are usually as just as they are eloquent. No man of equal creative genius

has been able to analyze so clearly, judge so fairly, and admire so fervidly the

music of others. Yet this literary labor was a source of great misery to a man

whose soul yearned toward another field of activity.

“I once remained shut up in my room for three days for the purpose of writing a feuilleton on the Opéra Comique, without so much as making a beginning. I do not recall the name of the work, but I remember but too well the torment it caused me. The lobes of my brain seemed ready to split ; burning cinders tingled in my veins. Now I leaned upon the table with my head between my hands, now I paced up and down like a sentry, with the thermometer at zero. I stood at the window gazing into the gardens, at the heights of Montmartre, at the setting sun ; reverie bore me a thousand leagues from my accursed comic opera. And when, on turning, my eyes fell upon the accursed title at the head of the accursed sheet, blank still, and obstinately awaiting my words, despair seized upon me. My guitar rested against the table ; with a kick I crushed its side. Two pistols on the mantel stared at me with great round eyes. I regarded them for some time, then beat my forehead with clinched hand. At last I wept furiously, like a school-boy unable to do his theme. The bitter tears were a relief. I turned the pistols toward the wall ; I pitied my innocent guitar, and sought a few chords, which were given without resentment. Just then my son of six years knocked at the door [the little Louis whose death, years after, was the last bitter drop in the composer’s cup of life]—owing to my ill humor, I had unjustly scolded him that morning : ‘Papa,’ he cried, ‘wilt thou be friends ?’ ‘I will be friends ; come on, my boy ;’ and I ran to open the door. I took him on my knee, and with his blonde head on my breast we slept together…. Fifteen years since then, and my torment still endures. Oh, to be always there !—scores to write, orchestras to lead, rehearsals to direct. Let me stand all day with baton in hand, training a chorus, singing their parts myself, and beating the measure, until I spit blood, and cramp seizes my arm ; let me carry desks, double basses, harps, remove platforms, nail planks like a porter or a carpenter, and then spend the night in rectifying the errors of engravers or copyists. I have done, do, and will do it. That belongs to my musical life, and I bear it without thinking of it, as the hunter bears the thousand fatigues of the chase. But to scribble eternally for a livelihood !”

It was while travelling in Austria and Hungary in 1844–45 [in fact 1845–46] that Berlioz wrote the greater part of his Damnation de Faust. This work contains, according to an eminent French critic, precisely that which is absent in the opera of Gounod—sympathy with the spiritual significance of Goethe’s drama. The composer staked his resources on the production of this work at the Opéra Comique in November, 1846, and two representations sufficed to ruin him. He set off for Russia in the dead of winter.

While in Russia and in Germany the genius of Berlioz was warmly recognized : why did the public at home so persistently reject him ? The main cause was an inherent antagonism of musical sentiment, while the enemies aroused by the composer in his capacity of critic, and the school-men he offended by his insuppressible originality, were the occasion of prejudice and ill-will. Early put forward, with Hugo and Delacroix, as an exponent of special doctrines that were to renovate the body artistic, Berlioz found himself in the heat of that battle waged between the two factions calling themselves the Romantic and the Classical, and felt the blows of both. He was abused for faults not his own, and exalted for qualities he neither possessed nor aimed at. His name became a target of wit for those who knew nothing of him beyond that name. “A physician who plays the guitar and fancies himself a composer,” said idle gossip ; and the criticism of the journals was chiefly gross abuse unparalleled except in the experience of Wagner. After the first performance of Harold in Italy the composer received an anonymous note commiserating him that he should lack the courage to blow out his own brains.

He had written an opera—words and music—founded on the Æneid. But the lyric stage was the exclusive possession of another. It had been foretold (by De Stendhal, was it not?) that one should arise to unite the profundity of Weber with the melodic charm of Rossini ; therefore when Meyerbeer appeared he was hailed and duly anointed. The lyrical drama of Berlioz consisted of two parts, the Taking of Troy and the Trojans at Carthage—the latter finally secured a score of representations at a minor theatre (1863). It is not Wagner alone who has planned the execution of his own works under perfect conditions, though it is he who has persuaded the world to grant them. “In order,” says Berlioz, “to properly produce such a work as the Trojans I must be absolute master of the theatre, as of the orchestra in directing a symphony. I must have the goodwill of all, be obeyed by all, from prima donna to scene-shifter. A lyrical theatre, as I conceive it, is a great instrument of music, which, if I am to play it, must be placed unreservedly in my hands.” But for him there was no Bayreuth. He saw his colossal Trojans—the work of his mature genius—cramped into the Théâtre Lyrique, criticised by all, amended by all ; dismembered, patched, and belittled to suit the capacity of orchestra and chorus, or to meet the exigencies of scenic resources. But this work yielded him a sufficient revenue to warrant his retirement from the Journal des Débats, and Berlioz left his desk after thirty years of servitude.

He was now sixty years old. Long since had that dream of his youth, that fulfilled promise of his manhood, passed among the bitter experiences of life. So early as 1842 a séparation à l’amiable was effected between two unhappy artists, “loving but rending each other.” Madame Berlioz was scrupulously, devotedly, cared for from the composer’s scanty income ; and when, in 1854, the once beautiful and renowned actress, so long left by the world to the oblivion of helplessness and pain, closed her eyes upon earth, he found himself overwhelmed with grief and pity—“pity, the sentiment of all others,” says he, “which it has always been hardest for me to endure.” His only child was cruising distant seas on board a man-of-war. He turned to the old home at Côte-Saint-André : all were dead. A lonely man, sadly broken in health, with the sharp sense of failure gnawing at his heart. Well-nigh quenched were the fires of an ambition that had seemed unquenchable. He no longer had courage to impoverish himself to get his music before a public sure to deride it. To one who had remarked that his music belonged to the future, he replied : “I doubt if it even prove music of the past.” Yet Berlioz was too philosophical not to know the blindness of the generations for contemporary genius—how in history the law of optics is set at naught, and men appear at their just size only through the perspective of years ; how the grandeur of the cathedral is lost upon the denizens of the pigmy dwellings in its shadow, going to and fro on everyday affairs. Yet it sometimes happened, even in Paris, that an audience felt itself suddenly, strangely moved, as by a presentiment of the greatness of the man among them. The following anecdote is related by a French critic :

“Some years ago M. Pasdeloup gave the septuor from the Trojans at a benefit concert. The best places were occupied by the people of the world, but the élite intelligente were ranged upon the highest seats of the Cirque. The programme was superb, and those who were there neither for fashion’s nor charity’s sake, but for love of what was best in art, were enthusiastic in view of all those masterpieces. The worthless overture of the Prophète, disfiguring this fine ensemble, had been hissed by some students of the Conservatoire, and, accustomed as I was to the blindness of the general public, knowing its implacable prejudices, I trembled for the fate of the magnificent septuor about to follow. My fears were strangely ill founded : no sooner had ceased this hymn of infinite love and peace than these same students, and the whole assemblage with them, burst into such a tempest of applause as I never heard before. Berlioz was hidden in the further ranks, and the instant he was discovered the work was forgotten for the man ; his name flew from mouth to mouth, and 4000 people were standing upright, with their arms stretched toward him. Chance had placed me near him, and never shall I forget the scene. That name apparently ignored by the crowd it had learned all at once, and was repeating as that of one of its heroes. Overcome as by the strongest emotion of his life, his head upon his breast, he listened to this tumultuous cry of ‘Vive Berlioz !’ and when on looking up he saw all eyes upon him and all arms extended toward him, he could not withstand the sight; he trembled, tried to smile, and broke into sobbing.”

Without the prestige of a virtuoso, without the vantage-ground of an official position, giving occasional concerts, generally in an unsuitable locale, with disaffected executants, the great composer was practically in the position of an amateur. What to him would have been such a band as that of the Conservatoire, or of the Opéra, which had been promised him, but was ungratefully withheld ! There was talk at one time of his becoming Capellmeister at Dresden, but this fell through. The very monarch of the orchestra was a beggar in his own kingdom.

It can not be denied that the music of Berlioz has inherent obstacles to its popularity. The elevation in sentiment, the refinement in details, the variety and complexity in form and rhythm, demand executants of the utmost skill, and in sympathy with the ideas of the composer. Besides, a genius so essentially orchestral can not be known through the piano score : that were Paul Veronese in photographic copies. It can hardly be wondered at that a public, hearing works of so original a character rarely presented and imperfectly executed, should fail to be impressed by them. The symphony of Haydn and Mozart had aimed to develop a theme, instead of a preconceived sentiment or action, and no attempts had been made to shape the course of the listener’s imagination. Beethoven was the first, as Hueffer says, “to condense the vague feelings, which were all that music had hitherto expressed, into more distinctly intelligible ideas.” The cheerful days of early art were passed ; it was no longer an Arcadian piping—not as when “Music, heavenly maid, was young.” The Muse led by Beethoven through the labyrinths of the Inferno emerged with changed lineaments—sad with the woe of humanity, wise with divine mysteries. “Behold,” as men said, looking with awe on the dark face of Dante, “the one that was in Hades !”

But Beethoven was a sealed book to the

French public—at all events, as his genius appeared in its final phase. A few

sonatas were essayed in the salons, and Liszt had played a concerto or two in

public. The symphonies were known only to the limited number of those in

attendance upon the concerts of the Conservatoire ; and it was not until

the very recent efforts of M. Pasdeloup at the Cirque d’Hiver that classical

orchestral music became popularized in Paris. Always readier to turn a witticism

than to hear and consider, the people were quite content with the opinions of

the professors. And it was for these, the official guardians of art, to charge

that the object of their ill-will had destroyed the specific, the consecrated

form of the symphony ; therefore they were constrained to exclude him from

the Conservatoire. The records of the Société des Concerts![]() show the greatest of French composers represented but twice in the course of

thirty years—by the early overture of Rob Roy, and a fragment of Faust.

This society possessed the field during that period, and that period comprised

the artistic life of Hector Berlioz. Here is the stigma.

show the greatest of French composers represented but twice in the course of

thirty years—by the early overture of Rob Roy, and a fragment of Faust.

This society possessed the field during that period, and that period comprised

the artistic life of Hector Berlioz. Here is the stigma.

So far as the technique of instrumentation goes, Berlioz’s supremacy is not denied ; his novel combinations, his knowledge of the resources of the various instruments, his skill in grouping, his success in orchestral color, have been the admiration of all. Concerning his method of study, he writes :

“I carried with me to the Opéra the score of whatever work was on the bill, and read during the performance. In this way I began to familiarize myself with orchestral methods, and to learn the voice and quality of the various instruments, if not their range and mechanism. By this attentive comparison of the effect with the means employed to produce it, I found the hidden link uniting musical expression to the special art of instrumentation. The study of Beethoven, Weber, and Spontini, the impartial examination both of the customs of orchestration and of unusual forms and combinations, the visits I made to virtuosi, the trials I led them to make upon their respective instruments, and a little instinct did for me the rest.”

One looks with wonder on this young provincial, an amateur of the flute, entering upon regular studies at an age when those darlings of genius whose cradles had been set in places so propitious—Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn—had already bound immortal shelves ; and who in half a dozen years from this time had written the Symphonic Fantastique : a work remarkable as the prototype of modern “programme music,” remarkable in the orchestral means employed, and in the use of a particular theme with a distinct dramatic purpose throughout. This idea of the leading motive has been beautifully treated in Romeo and Juliet, in which a theme is intoned by the choral prologue, in connection with the words indicating its sentiment, and for whose import we are therefore prepared on hearing it taken up in the body of the work, and wrought out by the orchestra.

There is a class of Berlioz’s works, called monumental, in which the style is imposing to the highest degree, and the means employed extraordinary. Such are his Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale, in which two orchestras and a chorus are employed ; the Requiem, in which four orchestras of brass are grouped around the grand orchestra and the vocal mass ; and the Te Deum, in which the organ at one end of the church responds to the orchestra and two choirs at the other, while a third choir of voices in unison joins from time to time. In contrast to these are that marvel of delicacy, Queen Mab, of which it has been said that “the confessions of roses, the complaints of violets, were noisy in comparison” ; and Absence, that incomparable Romance, which is to all other romances what Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale” is to all other odes—it is the very disembodied spirit of loneliness, the ethereal message itself on its longing way to the beloved.

It was the clearness with which he saw, and the keenness with which he felt, that gave its force to the character of Berlioz. He touched life at all points, and was in incessant vibration. His intelligence went like a plummet to the bottom of things ; his imagination kindled at a breath ; even his senses were abnormally acute ; the reciprocal action of mind and body almost phenomenal. An earnest, full nature that must express itself, checked, turned aside, and thwarted—a nature marked by sincerity and extreme sensibility, intensified into violent self-assertion by an opposition that threatened the very conditions of existence ; played upon beyond its natural powers—what wonder if it yielded at times jarring tones both in life and in art ?

“Whether or not Berlioz was a great genius will long be argued,” said Théophile Gautier, “the world being given to controversies, but none will deny that his was a great character.” Sorely pressed on all sides, he made no concessions. Before he had abandoned one article of his artistic faith he would have been hung, drawn, and quartered—which, in effect, he was. Hector Berlioz, pursued unto death for his loyalty to a pure musical ideal by a public dazzled by the scenic splendors of the Grand Opéra, drunken with the strains of the vaudeville, is our modern Orpheus torn by the Bacchantes.

He died at the age of sixty-five. His

funeral was held at the Church of the Trinity a few days after that of Rossini.

Gounod, whose Faust was running at the Opéra, pronounced the discourse at

the grave. Some eloquent things were said ; they quoted for him the epitaph

of Marshal Trivulce : “Hic tandem quiescit qui nunquam

quievit ;”![]() but

the ghost would not be laid. A twelvemonth after appeared that book of Mémoires,

still warm and glowing from the composer’s heart. Paris does itself the

justice to accept that which it had so long repelled ; at the

Conservatoire, the Cirque, the Châtelet,

the music of Berlioz is heard with incomparable enthusiasm.

but

the ghost would not be laid. A twelvemonth after appeared that book of Mémoires,

still warm and glowing from the composer’s heart. Paris does itself the

justice to accept that which it had so long repelled ; at the

Conservatoire, the Cirque, the Châtelet,

the music of Berlioz is heard with incomparable enthusiasm.

_______________________

* Mémoires

de Hector Berlioz. M. Lévy Frères. Paris : 1870. This work has

been translated by Mr. W. F. Apthorp.![]()

* Elwart’s

Histoire de La Société des Concerts du Conservatoire.![]()

* “Here is he quiet at last who never was quiet before.”![]()

![]()

* This article has been scanned from

our original copy of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine,

No. CCCLVII, Vol. LX, published by Harper & Brothers, New York,

in February 1880. The article does not bear the author’s name. We have

generally preserved spelling, syntax and punctuation of the original text, but

have corrected obvious misprints and missing French accents. Corrected dates

have been indicated in square brackets.![]()

![]()

Related pages on this site:

Berlioz in Germany (and Central Europe)

Berlioz Mémoires (in the original French)

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 1 September 2007.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains

Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil