“LES TROYENS” ON RECORDS

By

Robert Lawrence

© Robert Lawrence

Published in

|

“LES TROYENS” ON RECORDSBy Robert Lawrence © Robert Lawrence Published in |

|

EDITOR’S NOTE: In view of the current interest in Berlioz and the reissue of “The Trojans at Carthage” on the Ducretet-Thomson label, RECORDINGS reprints its review of the original issue (by Westminster) which appeared on September 27, 1952.

HECTOR BERLIOZ had two lifelong literary passions: Virgil and Shakespeare. As a boy, he had occasion to learn the “Aeneid” in the home of his father, a cultured physician who dwelt not far from Lyons; later, in Paris, he fell in love simultaneously with the works of Shakespeare and the actress who interpreted them, Henrietta Smithson. Identification with the British poet was to bring him one of the greatest successes of his career, the “Romeo and Juliet” Symphony, hailed even in his lifetime (Berlioz did not often meet with praise from his French contemporaries). Admiration for Virgil was to launch him on his last important work, “The Trojans,” and provide him with a scaffolding for failure.

No other work cost this composer quite so much suffering. Immersed not only

in the story of Dido and Aeneas but in a vision of all Mediterranean antiquity,

he composed both text and music. The result was an enormously long epic,

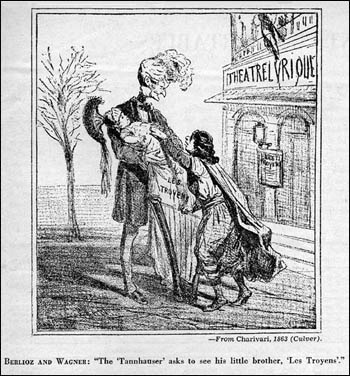

bypassed at first by the Paris Opéra in favor of Wagner’s revised “Tannhäuser”

and later ignored by that institution. Practical need for production finally

drove Berlioz to divide the work into two shorter operas: “The Fall of

Troy” and “The Trojans at Carthage.” The Carthaginian episode was

given during Berlioz’s lifetime; “The Fall of Troy” was never heard

by him.

This composer, as stylist, offers a baffling problem. The exuberance of his youthful works, such as the “Symphonie Fantastique” and “Harold,” their freedom of expression and bold handling of orchestral masses have earned him the tag of arch-romantic. Throughout his earlier years the creative pulse beat wildly. From the musical standpoint, however, he was always a formalist, a conservative whose love of balance and economy grew more marked with age. Many of the sounds made by his instruments were radical for the time; but the harmonies they played were traditional. The ascetic Berlioz of the last years conceived of “The Trojans” as a work in the direct line of his idols, Gluck and Spontini: noble, reserved, vast.

“The Fall of Troy” reaches the heights of classical drama. Strength and pathos are in text and music. The character of Cassandra is one of the great figures in opera, and the entrance of the Wooden Horse into the gates of Troy makes for an overwhelming scene. Less direct and more stately — also more cumbersome — is “The Trojans at Carthage.” Here, inspiration alternates with conventionalized arias and duets. The sound of the music is wonderful but the mood sometimes remote. Clearly, Berlioz is trying for the spaciousness of antiquity, vistas of great colonnades, the sphere of mythical heroes.

The recording of “The Trojans at Carthage” is virtually complete. Except for one inconsequential cut (the second stanza of Hylas’s song), all of the score has been faithfully presented. For the Berlioz student this is an important opportunity to hear a major work never yet given here in operatic form and rarely produced in Europe.

From the standpoint of pleasurable, rather than scholarly, listening the album is less attractive. It might have been wiser to record both sections of “The Trojans” with suitable cuts, selecting the best sections of each. As matters now stand, there are too many passages that wrap themselves around the shaft of the work like a parasitic growth, and threaten to strangle it. How much of the recording’s dullness is the fault of Berlioz and how much should be laid at the door of the performers (headed by conductor Hermann Scherchen) is hard to say, since presentations of "The Trojans” are too infrequent to have established any standards.

Most of the tempi are too brisk, with violations not only of metronomic markings but of dramatic effectiveness. Some of the orchestral playing, as in the ballet music, is brilliant. Other places lack nuance and occasionally, as in the horn solos of the “Royal Hunt,” accuracy. In an opera demanding great voices, the singers unfortunately do not measure up to the task. Arda Mandikian, the Dido, lacks the weight and color of the true mezzo-soprano; Jean Giraudeau, as Aeneas, has simply not the pealing tones required; and the others, except for an agreeable Anna (Jennine Collard) and an expertly sung Narbal (Xavier Depraz), are in the same gray vein. A definitive “Trojans” by major artists is still awaited.

![]()

* This article and the picture that

accompanies it have been scanned from a contemporary copy of the Saturday Review Recordings, 29 June 1957 (p. 33), in our collection. We have preserved the author’s original spelling,

punctuation, and syntax, but have corrected obvious typographical errors.![]()

We have not been able to contact the editor of this issue of the Saturday Review Recordings, which has ceased publication.

See also on this site:

Berlioz’s “Troyens”

at Covent Garden [1957]

Berlioz Discography – Les Troyens on records

Berlioz Discography – Les Troyens on DVD

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 21 August 2009.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Contributions Originales

Retour à la page Contributions Originales

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil