BERLIOZ’S “TROYENS” AT COVENT GARDEN

By

Ernest Newman

© Ernest Newman

Published in

|

BERLIOZ’S “TROYENS” AT COVENT GARDENBy Ernest Newman © Ernest Newman Published in |

|

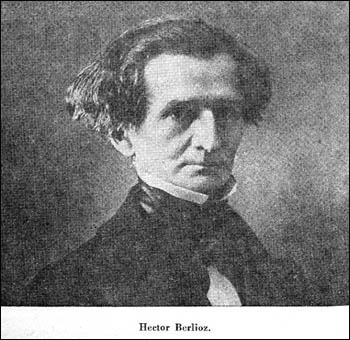

JUST about a century ago Berlioz was nearing the end of the composition of his opera “The Trojans,” which he fondly hoped would establish him artistically in Europe as a whole, or at any rate financially in his own country. He was at the very height of his musical and intellectual powers all through the 1850s (he had been born in 1803). The realization of the Trojan subject in music and in stage action cost him an immense amount of work and worry during the major part of that decade; and we are fortunate enough to possess a detailed record of his broodings upon the opera, his Herculean struggles with it, his frustrations and delights in connection with it, in his letters to Liszt’s paramour, the Princess von Sayn-Wittgenstein. The work was to prove, in the end, his Schmerzenskind. In Paris the national theatre refused to provide a home for it. A private impresario, one Carvalho, though he dared not undertake the financial risk of a production of the huge and exacting work in its entirety, finally put on the stage the second half of it — “The Trojans at Carthage” — though not without considerable mutilation of this. The remainder — “The Capture of Troy” — Berlioz never heard. He died, a tragically hurt and embittered man, in 1869.

From that day to ours the work has never succeeded in establishing itself in the repertory. For one thing, it is too long for a single evening yet not wholly

adaptable to two. Under ordinary opera-house conditions the two sections can be

compressed into one only at a certain expense to both; and in any case few opera

houses or impresarios have had the courage or the finance to tackle that

problem. A very intelligent Scottish musician, Dr. Erik Chisholm,  gave the work

in two evenings in Glasgow in 1935 with forces largely amateur.

The Oxford University Opera Club essayed it, under Professor Westrup, in

one-evening form in 1950: this, of course, necessitated a great deal of pruning.

Sir Thomas Beecham has given us two or three splendid radio performances of the

work under the auspices of the BBC; but the Covent Garden performance early in

June was the first wholly professional public one in Britain. Sundry cuts were

of course necessary, but not much that is really vital was sacrificed, and the

evening was naturally a very long one.

gave the work

in two evenings in Glasgow in 1935 with forces largely amateur.

The Oxford University Opera Club essayed it, under Professor Westrup, in

one-evening form in 1950: this, of course, necessitated a great deal of pruning.

Sir Thomas Beecham has given us two or three splendid radio performances of the

work under the auspices of the BBC; but the Covent Garden performance early in

June was the first wholly professional public one in Britain. Sundry cuts were

of course necessary, but not much that is really vital was sacrificed, and the

evening was naturally a very long one.

Hardly anyone in the large audience that night could have known anything at all of the work except the “Royal Hunt and Storm” music, which appears fairly frequently in our concert programs; so it was anyone’s guess what the general reaction of the audience would be. As it happened, there was no doubt about that from the beginning. Berlioz’s “classical” idiom, in which the opening scenes of the work are mainly couched, must have been, on the whole, novel to most of the listeners; yet it was manifest to every experienced and sensitive frequenter of musical milieux at the end of the first act that the audience had been moved to its depths; and as the long evening wore on, and the “romantic” atmosphere succeeded the “classic,” not a shadow of doubt could remain that here was one of the greatest achievements of nineteenth-century opera. The work has its little weaknesses: what long work in any genre has not? But there is a great deal of tremendously impressive music in it, and really dramatic music at that. Like all Berlioz’s music, this could have been written by no composer but himself; but he is as fully master of his idiosyncratic idiom as if, like most other masters, he had had a century’s traditions to guide and uphold him.

“The Trojans” is a truly stupendous work, and until a man has seen and heard it he can hardly lay claim to much more than a rudimentary knowledge

of the composer — certainly of the dramatic composer. Why then, one keeps on

asking, has it not succeeded in finding a sure place for itself in the world

repertory? The tentative answers to that question are manifold. The work, as I

have already said, is in its original — and alone authentic — form too long. It

makes enormous demands not only on the financial resources of an opera house —

for there is a large amount of fine “spectacle” in it — but on both the

musical and the  intellectual gifts of everyone concerned in the performance of

it. (I myself am in doubt whether an ideal cast for it could be assembled

anywhere today.) And the basic trouble is, perhaps, that only under the happiest

combination of circumstances can we imagine the “production” side of

the performance and the musical side being on the same intellectual level and,

so to speak, in precisely the same emotional key from first to last.

intellectual gifts of everyone concerned in the performance of

it. (I myself am in doubt whether an ideal cast for it could be assembled

anywhere today.) And the basic trouble is, perhaps, that only under the happiest

combination of circumstances can we imagine the “production” side of

the performance and the musical side being on the same intellectual level and,

so to speak, in precisely the same emotional key from first to last.

The Covent Garden performance was wholly satisfactory neither on the musical nor the “production” side, though there was much in both places that commanded admiration. Berlioz’s instructions for the staging are copious and definite; but at Covent Garden a good deal was done on the stage that should not have been done, a good deal was left undone that should have been done, and occasionally the right thing was done in an exasperatingly wrong way. I lack the space to substantiate these charges in detail: here I can only make them. Sir John Gielgud, the producer, is by profession an actor with, I am told, no particular knowledge of music; it was therefore only to be expected that he would do a number of things that either failed to do Berlioz justice or did him a positive injustice. The singing and acting, with Amy Shuard as Cassandra, Blanche Thebom as Dido, Lauris Elms as Anna, and Jon Vickers as Aeneas (to name only the principal roles) only now and then rose to full Berliozian height. Rafael Kubelik was the conductor.

Really to understand the mighty work demands a great deal more from the spectator-listener than just sitting in the theatre and letting himself be moved by what he sees and hears. One requires not only to know the score inside out but to be intimately acquainted with the first four books of the “Aeneid” — for Berlioz has done many things the clue to which (in Virgil) it has been impossible for him to work logically into the tissue of his stage action. The first thing to be grasped is that the whole purpose of the opera is expressed in the title. Its main subject is not, as many people imagine, the love of Dido and Aeneas but the Trojans — the long-drawn working-out by the rival gods and goddesses of the irreconcilable destinies of Troy and Carthage and Augustan Rome.

The modern scores are misleading on this point. There are not, as the title-pages of these suggest, two operas, “La Prise de Troie” (in two acts) and “Les Troyens à Carthage” (in four), but, as Berlioz’s original score makes perfectly plain, a single opera bearing the title “Les Troyens,” with explanatory sub-headings consisting of (a) Acts I and II “The Capture of Troy,” (b) Acts III, IV, and V “The Trojans at Carthage.” The distinction is vital. From first to last the destinies of Troy and Carthage and Rome, not the vicissitudes of any particular individual, even Dido, even Aeneas, have been the poet-composer’s central concern; and any production that does not bring this basic fact home to the spectator at every step has largely failed in its purpose. The problem is further complicated by the fact that while Berlioz has followed his adored Virgil step by step, the Roman poet tells part of the great story in his own person and part through the narrative and emotional comments of Aeneas. This procedure was bound to present Berlioz at two or three points with a tough problem of dramatic connection and suggestion which could not possibly be solved in the theatre. The inevitable result is confusion and mistake, the worst instance of this being the nonsensical placing of the wonderful Royal Hunt where it figures in the current scores and in the Covent Garden performance — as a “symphonic entr’acte” following the Carthage Act II. It is really not “symphonic,” and assuredly not an “entr’acte” in the original, but a dramatically significant tableau placed between Acts III and IV in the original score.

![]()

* This article and the pictures that

accompany it have been scanned from a contemporary copy of the Saturday Review Recordings, 29 June 1957 (pp. 31-32), in our collection. We have preserved the author’s original spelling, punctuation, and syntax, but have corrected obvious typographical errors. We have not been able to contact either the descendants of Ernest Newman or the editor of this issue of the Saturday Review Recordings, which has ceased publication.![]()

See also on this site: Les Troyens at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden; The première of Les Troyens in 1863; The Trojans : Texts and documents. — On Ernest Newman as a critic of Berlioz see the introduction to his earlier article of the 1890s on this site.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 21 August 2009.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Contributions Originales

Retour à la page Contributions Originales

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil