Published in

The Musical Times, 1 September 1903, pp. 594-596

This page presents an article written by Charles Maclean, the Special Correspondent of The Musical Times, on the occasion of Berlioz’s centenary celebrations in August 1903 in Grenoble. The manuscript of the article is dated: Grenoble, August 21. We have preserved the original syntax and spelling of the text, but corrected obvious type-setting errors.

See also on this site The centenary of Berlioz’s birth in 1903 in Grenoble.

![]()

Roman noses and no Jews. If one might preach from a text, it would be that. The traveller from Lyons to Grenoble, feeling to the left with the distant Mont Blanc, and crossing the Rhone, is conscious that he has met a new population. He has entered the country of the Isère and the southern Dauphiné. ‘Le Dauphinois fin, faux, et courtois.’ The ambitions of rulers, the political swayings of peoples, have upset ancient and natural geographico-racial distinctions. But the fact remains that west of the Rhone is Gaul, and east is Italy. The Isère is the river of mightiest volume next after the Rhone in what is now called France, and beginning with this important Isère land straight across to the Gulf of Venice is a great belt of country which is the true home of the Latin race. Grenoble, the capital of Isère, once the capital of the whole Dauphiné, is in the same parallel with Verona, Virgil’s Mantua, and Venice. Only lying among the foot-hills of the juvenescent French western Alps, this Isère land has many of the attributes of mountain regions ; and they have given to it its distinctive national character, its loyalty to itself, its impatience of any controlling exterior power, even its narrowness.

The Roman nose is no figure of speech. It meets one in every street, in every public conveyance. This, the grave long faces of the men, and the very beautiful eye and brow of the women, show the traveller that he is in effect in Italy. A few days ago at a public banquet I sat opposite Berlioz appallingly redivivus. The classic features, the very high crest of hair over the right temple, were Berlioz himself startlingly in the flesh. It was M. Charles Berlioz, grandson of the uncle of Hector Berlioz ; an amiable painter, with whom much conversation. In a toga he would have been exactly a typical Roman patrician senator. And as to the Jews. With the dawn of electricity, and the huge water-power here awaiting use, it cannot be doubted that sub-Alpine countries like this have their commercial future. But for the moment they are shut in undeveloped. The Isère country is as yet content with its vineries, its distilleries, its glove-making, and so forth. In such conditions the Jewish race, powerful in commerce, all-powerful in musical art, does not step in. The absence of Jewish physiognomy in the streets is very striking to one who has left European capitals. Racially, Berlioz had far more occasion to feel himself opposed to Judaism than had Wagner, though he does not seem to have troubled himself on the subject. Artistically, almost the chief significance of his music lies in the fact that it was wholly free from Judaic influence. Add to all this that Berlioz is the only creative musician who has ever proceeded from the Dauphiné, and the present sermon will have been displayed. Lombardy has done or is doing its work, but this is the sole effort so far of the westernmost limb of the purely Latin country. A lutist to Anne of Austria, one Ennemond Gaultier of Vienne, is not countable.

And what made Berlioz a poet ? It is the heart more than the head which makes the poet. Berlioz found his sensibility in red boots and a winning eye, in Estelle Gautier at the village of Meylan in the valley of Graisivaudan, in a three-weeks’ holiday each year with his uncle Colonel Marmion, late of the Lancers, and then eleven months for cherishing the short-lived romance,—a very old and very common story indeed. Red boots can still be seen crossing the Grenette square at Grenoble, and boys of thirteen will fall in love with girls of nineteen, and consume themselves with passionate regrets during absence, as long as the world lasts. But the beauty of Berlioz’ heart lay in that he never forgot those pure powerful impressions. He married two women, neither of them particularly worthy ; and when he had done his fullest duty by both, his heart attorned again to one who was worthy enough, but perhaps insignificant. She was free to indulge his respect, yet scarcely realized that the greatest musical intellect France had ever produced was at her feet. The most luxuriant ivy clings to dull masonry. An injustice may be done, but so it seems from her published letters. A young gentleman who is a clever musician and a successful man of letters, has recently described this exquisite passion of Berlioz as ‘half senile.’ The greatest punishment to wish him is that he should feel the same at sixty, and be so interpreted. To those whose life has not been choked with tares, love can be fresh at sixty as at sixteen. I have wandered through the lanes of Meylan in that valley of Graisivaudan which is the most gorgeous, and one of the most fertile, in France. The valley is marvellous with its snow-capped Belle Donne, its rocks of Saint-Eynard, its enormous firs and pines, mixed with alder, ash, aspen, beech, birch, maple, oak, willow, and what not ; through all, the stately Isère running. This is the home of the serpent-fairy Mélusine. A contrast to the verdant but uniform-level plain which met Berlioz’ eye at his own home of la Côte or vineyard-slope of St. André. A dozen years later in the Campagna he learnt to open his heart to nature, as before he had opened it to passion ; but for him nature was still always focussed in the memory of Meylan and the gorges of Graisivaudan. Round this inmost feeling raged all the storms of his ambitious intellect.

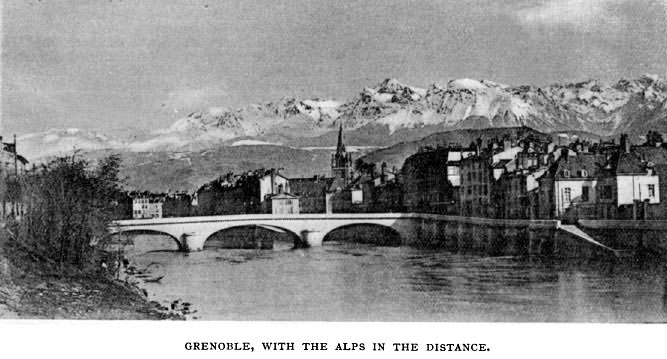

Those good friends of our short-jacket memories, the Albigenses, were the earliest known inhabitants of the Isère country ; and very stiff opponents the Romans found them, in their mountains now called Pelvoux, Grandes Rousses, Belle Donne, and Grande Chartreuse. Rome colonized them at two centres ; Vienne to the west, and Cularo or Gratianopolis or Grenoble to the east. Then succeeded Burgundians and Merovingians. Then five great mediaeval baronies. Then the priest Bruno founded the Chartreux order (1084). Then the counts of Graisivaudan in the I2th century took a dolphin into their arms, and the whole country was sold to the French crown in 1349 on condition that the heir-apparent called himself the Dauphin. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes under Louis XIV. drove out all the Protestants. When Louis XVI. tried to suppress its local Parliament, Grenoble on June 7, 1788, went into revolt, and sounded the first note of the great French Revolution. On the other hand in March, 1815, it re-opened France to Napoleon returning from Elba. Since 1830 it has had little history. Personages of the Dauphiné best known to us are :—Pierre de Terrail, seigneur of Bayard (1476-1524), the Calvinist F. de Beaumont (1513-1587), the statesman Boissieu (1600-1683), the philosopher Condillac (1715-1780), the engineer Vaucanson (1709-1782), the novelist Stendhal (1783-1842), the glove maker Jouvin (died 1844), and Hector Berlioz himself (1803-1869). The indigenous language is the ‘romane provençale,’ the religion almost wholly Catholic. It is a centre of practical botany. Its chief industries, cement-making, glove-making, and the concoction of those most noxious disguised brandies called ‘liqueurs.’ Grenoble has an uninteresting Cathedral with a heavy 11th century tower ; it is called the capital of the French Alps. It is a bright sparkling town in a magnificent mountain horseshoe, and it is rather shrewd than intellectual. Such is the native country of Berlioz—a Latin of the Latins, a Dauphinois of the Dauphinois plus passion.

It is more difficult to be an original Frenchman than an original anything else. The speech alone of the French shows them swathed in convention. Though when quite natural they speak like the rest of mankind and very musically, the conventional mode of speech in the middle classes is a perfectly accentless mock-timid chip-chop ; perhaps more striking than our society drawl, certainly more universal. Berlioz’ power consisted in that no conventionality could hold him. A grown-up young man (he was inscribed on the Paris Conservatoire books on August 26, 1826), he left his native country an absolute know-nothing on the technique of music, but with a mature soul and himself a very firebrand of originality. If he was not a ‘natural musician’ (as some say), the words have no meaning. He became one of the greatest musicians of all time. His originality has made him subsist to this day ; indeed he is now beginning.

The Grenoble administration put their Berlioz birth-centenary Fêtes (August 14 to 17, 1903) four months in advance, because it would have been absurd to hold them in mid-winter. They must put the town en fête ; they must have an audience. The chief amusement of this part of the country is the competition of open-air bands and unaccompanied choral societies (Orphéonistes). Now and then a large competition attracts ‘societies’ from all parts of southern France, as from Switzerland, Italy and Algeria. The bands are of all composition, from cavalry ‘trumpet bands’ to what we should call sea-side open-air bands. One hundred and fifty-seven Societies came on this occasion, eighty-four jurors were drawn from all parts, and competition (gradually converging) went on in selected localities of the town according to an elaborate classification and organization. The whole were disposed of in three days. Not much grumbling, and a great deal of excitement. The chief prizes were taken by Geneva, Lyons, Tunis, and Turin. But medals were given passim. Then the business of unveiling, in the Place Victor Hugo, the new Berlioz statue, from the cast of an excellent Grenoblian violinist-sculptor Urbain Basset, which won a Paris Salon prize in 1885. It is really very fine, and quite as good as Lenoir’s now in the Place Vintimille, Paris, and at la Côte St. André. Berlioz has his hand to his head as if listening. The unveiling ceremonies were performed in atrocious weather, which seems to pervade the world. Then came a representation of ‘Faust’ in the Theatre, by the Aix les Bains chorus and orchestra under Jéhin, with principals Lina Pacari, Laffitte, Dangès, and Ferrand. The best of the principals was Laffitte, the tenor. The performance, wholly given over to expression in detail, yet controlled in block by an excellent conductor, was distinctly a revelation. If this be a standard, the vocalizations of Berlioz music heard in England are a parody. There was not a moment of excess in effect, yet a surcharge of emotion. This is undoubtedly the true Berlioz, given by those of his own race and country, and we have to learn. The only distressing point was the frequent falling in pitch of the female singers ; of which the musicians were aware, and the critics not at all. A quantity of miscellaneous Berlioz works were given at the other concerts, which to save space will here be passed over. Again in the instrumental pieces it was evident how the Berlioz omnipresent soloism differed from the Wagner omnipresent diffusion and broad lines of tone-colour, and how all depended on the spirit of the individual. Yes, even here we have to learn. Weingartner took from the band a most stimulating rendering of the ‘Fantastique.’ When they gave him a crown, he put it round the score ; upon which great applause. If the Dauphinois are, as Berlioz said, innocent of music, they have managed this affair very well. It is not known why Colonne did not come ; it is still less known why the French Government (in contrast to the German Emperor with Wagner) took so little trouble to be represented.

One place has been well-nigh forgotten, la Côte itself. It is 30 or 40 miles from here, and is to have its own Berlioz fêtes on the 22nd and 23rd. I did not omit to go there ; nor indeed 9 miles farther to Beaurepaire, for the great-grandmother of Berlioz was a Dauphinoise and a de Beaurepaire. The Côte resembles its kind, as a long, straggling, fairly well built, and monstrously dirty provincial French village-town. The inhabitants are handsome and polite. Berlioz’ statement that he lived in a small way over a farriery, whence his rhythm, was a joke. The Berlioz house is exceedingly fine, top to bottom, in and out, and the farriery (now no more) was over the way. The house is in Rue de la République. Sold by the family to one Paillet. By him sixteen years ago to M. Manquat, a merchant, whose indulgent lady showed every corner of it. The little room where the boy slept, next the large handsome drawing-room, was very affecting. Berlioz museum now being formed in a room in the house. Immediately after his Monday evening concert in Grenoble, Weingartner, due in Munich on Wednesday, dashed forth with the Mayor of la Côte St. André, M. Meyer, covered the 35 miles in automobile at a rate probably greatly exceeding the law, and laid a wreath at the foot of the Lenoir statue in Berlioz’ real birthplace. Midnight scene. Illuminations. Weingartner embraced the Mayor !

CHARLES MACLEAN.

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 1 February 2013.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

Back to Contemporary Performances and Articles page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains

Retour à la page Exécutions et articles contemporains

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil