By Helen Spills

The Etude Music Magazine, January 1944, p. 19, p. 52*

© Helen Spills

THE TRULY FINE BODY of modern French art-song which we know today did not appear until after the middle of the nineteenth century, nearly fifty years after the wonderful florescence of cultivated solo song that began in Germany with Franz Schubert. The period which preceded that of the art-song in nineteenth-century France coincided with the troubled era of the Revolution, the Empires, the Restoration, and the Revolutions of 1830 and 1848; a time of intense feeling. Under such conditions patriotic songs were found in great abundance. At the beginning of this period the French had no lyric poet of the stature of the German Goethe to inspire to song creation, and had there been one, the general state of music composition in France would not have provided the necessary musical means for art-song creation in the sense that we understand it today.

At this period were to be found the romances of Garat, 1764-1823, a distinguished composer and singer of Romances, who was feted and admired by Marie Antoinette and her court at Versailles, and later was made professeur du chant at the Conservatoire by Napoleon. The songs of this time had facile, pleasing melodies, but were rather thin in texture and simple in construction. Their composers were more or less identified with the composition and production of opera in various forms, and also provided music for the numerous State entertainments and other public functions of their day.

A Poetic Array

With the beginning of the century of Romanticism in France there appeared a great array of lyric poets; singers deeply responsive to the era. First in the line came the idealistic Lamartine, and the more intellectual de Vigny; then that passionate and charming lyricist Alfred de Musset; and, at last, the classical Gautier. Over all these, and over the whole century, hovers the personality of France’s “mightiest gatherer of words since the world began,” Victor Hugo, 1802-1885. For this wonderful outburst of romantic lyrics the complementary musical themes were generally lacking, but there was one during the first half of the century who sought bolder effects and greater originality in song. He was François Louis Hippolyte Monpou, called the bard of the Romantic “cenacles,” and popular with Victor Hugo and contemporary French poets of his time, whose verses he set to music. However, Monpou had too little musical learning and fell short in the matter of genius, and his songs have not endured.

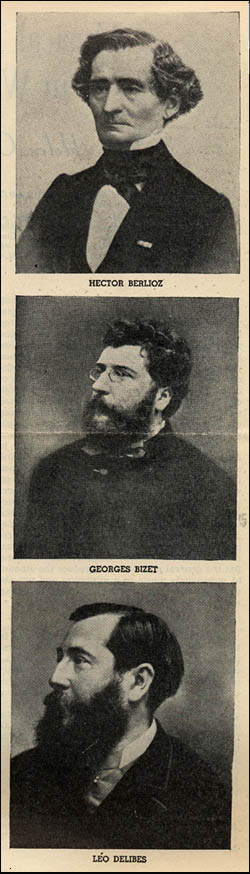

In Monpou’s time there lived another French composer, whose name and fame have since been the signal for heated discussion pro and con as to his

legitimate right to his position of musical eminence. This composer was Hector Berlioz, 1803-1869, entirely a man of his time. His highly strung, passionate, and enthusiastic temperament eagerly embraced the new musical message from Gluck,

Weber, and Beethoven, which came to him as a youth in Paris. Though Berlioz is celebrated first for his innovations in the field of orchestral composition, he has shown himself, by his songs, to be also the first of French composers really to venture in search of truly expressive solo song and to leave worthy results of his efforts.

eminence. This composer was Hector Berlioz, 1803-1869, entirely a man of his time. His highly strung, passionate, and enthusiastic temperament eagerly embraced the new musical message from Gluck,

Weber, and Beethoven, which came to him as a youth in Paris. Though Berlioz is celebrated first for his innovations in the field of orchestral composition, he has shown himself, by his songs, to be also the first of French composers really to venture in search of truly expressive solo song and to leave worthy results of his efforts.

A Tonal Adventurer

When we consider the sparse musical foundations upon which Berlioz had to begin his career and the low level of musical taste current in Paris at the time of his first visits, his courage in striking out into new paths and his ultimate accomplishment seem great. In his music, as Berlioz states, he “determined on enforcing the inner meaning of his subject"; this he seems to have aimed to do in his songs, mainly by means of richer harmonic color and other modes of expression very unusual in French song in his day, and entirely foreign, at that moment, to French ideas of musical art.

His group of songs called “Les Nuits d’été,” composed in 1834[sic]**, consists of musical settings of six poems by Théophile Gautier. Romain Rolland calls attention to a certain classical quality inherent in the music of Berlioz, which manifests itself in spite of Romantic harmonies, color, and exotic rhythms; we find this quality in the songs. Those of “Les Nuits d’été” are well contrasted and exhibit far greater resourcefulness in the matter of musical expression than had yet been found in French song. An effective song in this group is the lamento Sur les Lagunes, which opens with the words “Ma belle amie est morte. . . .” (My beloved friend is dead). The whole work expresses the almost immeasurable grief of one at the loss of a dear friend.

Here Berlioz has used a short musical figure which recurs constantly throughout the accompaniment and which is the last thought left by the voice; a sort of idée fixe which evidently functions to intensify the element of grief. It seems like the mournful tolling of a bell during the lament sung by the voice. This song works up to fine dramatic proportions before it ends on a final repetition of the theme of the tolling bell which reverberates softly in the final measures of the accompaniment. Berlioz, here, used methods far in advance of his time.

In Contrasting Vein

A very different song from the lamento is the first in the group “Les Nuits d’été”; it is called Villanelle. This is a lovely song of spring with a chordal accompaniment of shimmering, iridescent, delicate color (sempre leggiero), and a melody that seems to take wings and soar aloft like a bird. L’Île Inconnue, with its rocking, barcarolle rhythm, has an eminently fitting musical setting for the light and playfully tender nature of the poem. Au Cimetière suggests the later French Impressionists in the wavering, evanescent quality of its melody, and the pale, misty coloring evoked by the changing harmonies of the accompanying chords.

Thus we find Berlioz, celebrated as a daring explorer and innovator in the field of orchestral composition in France, also a pioneer in the composition of French art-song. Into the last entered all the current Romantic play of color, of light and shade, tinctured ith strong emotional content, and withal distinctly French in feeling and expression. Berlioz did not institute an era of French song, however; due, undoubtedly, to the unfortunately hostile feeling his works at first aroused in his own land, and also to the fact that he composed relatively few songs. His influence made itself only indirectly felt when French art-song reached its full stature in the last half of the nineteenth century.

After Berlioz came Saint-Saëns, Gounod, Massenet, Godard, and other instrumental and operatic composers of the time who added to the general body of song literature in France, but their contributions were not outstanding except perhaps in individual instances. Gounod and Massenet are credited with instituting a school of song in which the melody functioned as the expressive feature, and the accompaniment too often was merely what the name implies. Sometimes it showed significant workmanship, but rarely stepped out of its chief role—that of support for the voice.

In Georges Bizet (1838-75) and Leo Delibes (1836-91) we have two whose songs at this time present, as a whole, a high level of excellence. They are formal in design and yet touch hands with the Romantic era in the greater richness and color they display. These expressive, romantic qualities are achieved by harmonic and rhythmic resourcefulness; and, as has been noted in Delibes’ art, and equally in that of Bizet, a “highly distinguished” line of melody. Bizet and Delibes were mainly occupied with works for the stage, and it is for these that they are chiefly remembered; but their songs, though few in number, are plainly an advance over those of most of their contemporaries and exhibit their receptiveness to the new musical thought of the day.

The French Tradition

Another who showed daring and fearless departure from habitual musical usage of his time was Emmanuel Chabrier, whose charming and witty Villanelle of the little Ducks is the most celebrated of his few songs. With Bizet and Delibes, Chabrier may be said to have instilled red blood and life into the often-too-sugary song of his day. Before the earthly careers of Bizet, Delibes, and Chabrier had ended, a rich outpouring of modern French art-song had begun; an outpouring which followed upon the heels of important instrumental and orchestral developments in France, which were first noted about the mid-nineteenth century, and which led to a significant and native musical art, a “recapture of the French tradition” after many years. These developments, coinciding with the appearance of a great French lyric poet in the person of Paul Verlaine, provided the musical and poetical means necessary to the production of a fine body of art-song.

By the end of the century there had emerged a notable French song with such masters as Fauré, Debussy, Duparc, Chausson, Ravel, and others in whose works we rejoice today. Yet the song creations of Berlioz, Delibes, and Bizet should not thereby have lost caste. Among these are gems entirely singable and truly worthy of a place among representative French songs.

![]()

Notes.

* This article has been transcribed from a contemporary copy of this article, published in The Etude Music Magazine, January 1944, p. 19, p. 52, in our collection. We have preserved the author’s original spelling, punctuation, and syntax. We have not been able to contact the editor of this issue of The Etude Music Magazine, which ceased publication in 1957.![]()

** The 1834 date is incorrect. Berlioz composed the first version of these six songs, for voice and piano, in 1840-1841; he later orchestrated them in 1843 (Absence) and

1856 (the other five).![]()

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 1 June 2010.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Contributions Originales

Retour à la page Contributions Originales

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil